This text course is an edited transcript of a MED-EL live webinar on AudiologyOnline. Download supplemental course materials.

Learning Objectives

Today, Participants will be able to list play milestones for children ages birth to six years, describe auditory strategies to use when facilitating listening and spoken language development, list an auditory hierarchy along with goals at each level, and develop purposeful play activities that specifically target listening goals.

Purposeful Play

One of the first things we need to know when we are working with children is how to play, so we should know play milestones that are appropriate for young children. The two key things we need to know when we are developing listening skills are auditory strategies that we can use to facilitate the listening hierarchy and the current level of a child’s skill and where we want them to go to. We also need to know appropriate goals at each level that will help facilitate acquisition of that skill. Then I will talk about these levels and goals with purposeful play activities.

Purposeful play is a lesson plan. We need to know at what level of skill they are on the hierarchy, and we have to choose some appropriate goals. When we are coaching parents or new clinicians, we need to write out some scripts that we would say to help facilitate that goal. Purposeful play helps to set up a lesson play and give some ideas for parents to implement at home.

Why do we choose play? Play is the work of children. It also contributes to physical, social, emotional, cognitive, intellectual, and communication development. It is also fun. When we are working with children and trying to develop listening or auditory skills, it is hard work. It is also new to them. If they are profoundly deaf and now have a cochlear implant, sound is new to them. It does not mean anything yet, and t can be scary. We want to make it fun and motivating for them. Therefore, we play.

Types/Stages of Play

Defining the stages of play goes back to Mildred Parton in 1933, who looked at children between the ages of two and five years; she described six different types of play.

Unoccupied Play

The first stage is unoccupied play where the child is relatively stationary and doing random movements. Young babies do this

Solitary Play

Next is solitary play where the child is engrossed in playing, but does not notice other children. The play is about the toy and the play itself. This occurs in young children under 12 months up to about two years. They may give you eye contact, but when they are playing with the toy, they are not trying to get you to come play with the toy with them.

Onlooker/Spectator Play

In this type of play the child starts to take an interest in other children and with what they are playing, but they do not join in. They primarily watch. This happens at two to two-and-a-half years of age.

Parallel Play

Parallel play is where they watch other children and mimic the children’s play. If the other children are playing with blocks and stacking them, they may take blocks and stack them up, but they are still not actively engaging with the other children. The focus is still on the toys themselves rather than social interaction. That is at two-and-a-half to three years of age.

Associative Play

Now we start to see children showing more interest in other children rather than the toys. This is where social interaction starts to appear, about three to four years of age.

Cooperative Play

Between four and six years of age, we finally start to get to cooperative play. Children are now socially interacting with other children and some kind of organization enters into their play goal. They are doing activities together, and there are rules to a game. Based on these levels, if you are trying to get a two-year-old to do a group interaction, it will probably not work very well; think about where children fall on this continuum.

Play Milestones

The exploratory stage is from birth to 24 months. Beginning use of toys appropriately starts around nine to 12 months where they might start to roll a ball or take an airplane and fly it around rudimentarily. Parallel play comes in at two-and-a-half to three years where they watch the other children and mimic what they are doing. It is not active interaction.

Cooperative play can start around three to three-and-a half years of age, but becomes more solid around four to five years of age. At three to four years of age, they will like to start some simple board games, but they need to have manipulatives, such as Chutes and Ladders. My personal experience when you are doing those kinds of games with manipulatives is that you do not always follow the rules closely. You have to be able to bend them a little bit to keep the child’s interest and motivation with what is going on.

Turn-taking and sharing is around three to four years of age. They prefer to play in small groups. They like to work on projects like cutting and pasting around four-and-a-half or five. Therefore, I will not try cut and paste activities with a three year-old.

Again, cooperative play is four to five years of age. By five to six, they are able to play games that have rules. Now you might try to play manipulative games with all the rules that are involved.

At five to six years of age, they are playing in groups and are more imaginative. They are making plans, and the play has many sequences. A note from my personal experience is when I am playing games with the children up to five and six years of age, I always lose. I want the child to be motivated. I want them to enjoy coming to therapy and have it to be a positive experience. Little children do not like to lose. I have found that if they were losing at games, they would get upset, shut down or pull away, and I would lose their attention. They do need to learn that they cannot always win, but I explain to parents why I am doing it, and that is something they can work on at home. When they are six or seven, depending on the maturity of the child, then I will start to occasionally win at a game.

Auditory-Verbal Therapy Strategies

What else do we need to know when we are trying to develop listening skills? We need to know some auditory strategies.

All Waking Hours

During all waking hours, the child should be wearing their cochlear implant or hearing aids. That is obvious, but it is something we need to describe to parents. If the child is only wearing it two hours a day, they are not going to develop listening skills at the rate they otherwise could.

Come Close to Me

Next is come close to me. When speaking to the child, do not have your back to the child. Do not be 15 feet away or in another room, especially when the child is in the very beginning stages of learning to be able to listen and attach meaning to sound. We want that child to be close. For children with hearing aids, the listening bubble is even smaller than it is if you have a cochlear implant. Being close to the child, especially when you are providing them with new or novel information is important.

Talk More

As a speech-language pathologist, this is an easy one for me because I like to talk. Some parents are not as comfortable with talking, narrating, and describing what the child is doing or describing what is going on. We have to encourage, model and coach how to do a lot of talking. If the child is playing with the cars, the mother and father get involved and say something like, “Oh, that is a blue car. That blue car is like a racing car, and it can go really fast. Look, you are going to make it go fast.” They need to use all that language. Talk, talk, talk.

Auditory Hooks

We use auditory hooks or the learning-to-listen sounds. They are words or phrases that have a lot of sing-song to them to grab the child’s attention. They can then start to develop some understanding of the language that goes with that object or action. We use these in routine, familiar, and repetitive situations. This is motherese and how typically hearing children learn. They do not learn “no” at nine to 12 months. They learn “No!” with a lot of emphasis and intonation. This is what they pick up. Auditory hooks give as much acoustic information to that child as possible and helps them recognize it repetitively, while attaching that word or phrase with the object or action that is taking place.

Thinking Place

This is joint attention, where you and the child are focused on the same thing. I know you want to follow the child’s lead, but you also want to make sure that the child and you are attending to the same thing long enough that you can input language for the child. If you have a very active child and you are trying to follow his lead, you can say, “Oh, you have the blue car.” Suddenly he drops the car and runs to the other side of the room and starts grabbing at the farm and opening the door to farm animals. You follow him across the room and you say, “Oh, you found the cow. The cow says moo,” but he has already dropped the cow and is back to the other side of the room and picking up a ball to throw it. You say, “Oh, you have a ball. Bounce, bounce, bounce,” but he has dropped the ball and is off to something else. If you are doing that kind of thing, you can imagine how little language that child is really focused in on. The thinking place is not happening.

You want to make sure that you both are in the same spot. If you are putting blocks in a bucket and you say, “We are going to put it in. We are going to put it in. We are going to put it in,” the child should be putting it in as you are saying it, and they are listening to you. They can hear you say “put it in” and learn that that means describing the action of “putting it in.” We always want to make sure that we have the child’s joint attention.

If the child has a diagnosis of autism, we particularly have to work on communicative intent. We want to look at where the child is, and for some children, we have to work at it a little bit more to be in that same thinking spot.

Acoustic Highlighting

Acoustic highlighting is an easier one. You highlight a sound or a word to draw attention to it. This is helpful when you are working on auditory memory or trying to teach vocabulary. An example is, “Go get your shoes,” with emphasis on the word shoes or, “Go get your shoes and give them to Daddy.” Here you are trying to emphasize shoes and Daddy so that they can pick that out. In articulation, we are always trying to get the child to use listening to be the first point of correction so they start to rely on their listening skills.

I was working on inferencing with a little boy in first grade. I said, “stewardess.” He said, “tewardess.” I said, “No, no, listen.” Instead of doing all kinds of rhythmic phonetics or showing him by watching my mouth, I said, “Ssssstewardess.” I acoustically highlighted the “s” and he was able to come back with it. I used his listening to correct the articulation. We need to work on listening first.

Auditory Sandwich

The auditory sandwich is the listening piece. Give the child a chance to listen first. My rule of thumb is three chances. If you have said it three times and they do not understand it, then give them a cue or support to attach meaning to the sound. You could stand there all day and say, “Get your shoes. Get your shoes,” but if they do not know what the shoes are, they will not do it. Present auditory first, then provide a support that helps attach the meaning and that could be a point, a gesture, a sign, or a glance over at the object. If I am saying, “Give it to Mommy. Give it to Mommy,” and they are not getting it, I will say, “Give it to Mommy,” and I will glance over at Mommy. That is enough for them to make that connection. Then you have given the visual, but always go back and put it back into the auditory mode. This will help them learn to listen and rely on their auditory skills.

Checking for Comprehension

Ask a child specific questions about the information presented. If you want to say, “The cat jumped down from the bed,” you ask the child, “Who jumped down?” or, “What did the cat do?” Does the child understand specific information presented in what you have said, which is a little bit different?

Checking for comprehension is not asking if they heard it. They will all nod their heads and say they heard it. You may not be sure if they did hear it or whether they understood, but these are two different things. One is the access to sound and not hearing it, and the other is the comprehension of sound and not understanding it. “The cat jumped out down from the bed.” Who or what jumped down from the bed? If they answer the cat, then you know then comprehended it.

Ask What They Heard

Asking what they heard is having the child repeat. I find this particularly useful when I am looking to see if they have auditory memory or auditory discrimination. Was it a memory, comprehension, or an access issue? One example would be if I am having a child do some recall and we are putting objects and toys away. I might say, “Let’s put away the fish, the cow, and the dog.” The child picks up three things and throws them in the bucket. “Now let’s put away the cat, the elephant, and the boat.” The child may pick up the cat and the elephant, and then they hesitate. Instead of me repeating it, I might say, “What did you hear?” They might say they heard cat, elephant, and book. Book and boat is an auditory discrimination issue, and he was confused because there is no book to pick up. Therefore, he did not understand what he was supposed to do. Asking what they heard is nice way to determine where the breakdown occurs – memory, comprehension, access or discrimination.

Others as a Model

Another strategy is to use the parent, sibling or other as a model. It is to help provide an appropriate response for the child, and then the child is given a chance to respond. I think we need to be vigilant when we are working with these children that they are always on the spot. We should be expecting a lot from them, always having them show us something, point to something, and doing something. It is a lot of pressure on them. We do not want them to feel pressured. We want them to have fun and learn, but we do not want it to be stressful.

You might say, “Can you give me the cat?” and they are not able to give you the cat. We can then use different strategies such as say it three times and then give a cue, but we could also use this strategy. I may be thinking that the child has not learned the word cat yet, so I might turn to mom and say, “Mom, you do it. Can you give me the cat?” Mom will pick up the cat. Therefore, the pressure is off of the child and he can associate the word cat with what mom has picked up. He sees what it is, but does not have to feel like he failed because he was not able to do it. It provides a break for the child if everyone is taking turns. It is important that they always feel successful.

Expand

Expanding is an expressive language strategy. We want to respond to the child. For expanding, we want to correct the grammar and recast it into an adult form. If the child says, “Daddy go,” we would say, “Daddy is going.” In a very natural way, you say, “Yes, Daddy is going to work.” You can do some highlighting in there. You are not telling the child they said it wrong. You are giving them the adult form, and then moving on. Again, they will not feel like they got it wrong, but they are hearing the appropriate form. We want to put it into the grammatically correct form so they get that stimulation in that model.

Extending

Extending is another expressive language strategy. If they are giving us some simple sentences that are appropriate, we want to push them along and extend a bit more with new information to add. So if the child says, “Daddy is going to work,” you can say, “Yes, Daddy is going to work because today is Monday, and he has to work today.” We want to expand with the correct grammatical forms and extend to add new information. Another example is, “Look Mommy. The dog is running.” Mom can say, “Yes. Look at that. That big brown dog is running.” This adds in some adjectives for the child.

Clarification

Checking comprehension is teaching children clarification skills as they get older, at five or six years of age. They need to start to self-advocate. When a breakdown occurs, it is not appropriate for them to constantly say, “Can you repeat that?” or, “I didn’t hear you.” It might be that they did hear, but they do not understand the vocabulary. It may be that they did not hear, but they need to say, “I did not hear that word,” or “I don’t know what that word means.”

With one child, I purposely picked an old phrase and I said, “The stewardess brought the passenger his dinner. Where was the passenger?” I knew the six-year-old did not know the word passenger and no one uses the word “stewardess.” Instead of the child asking for me to say it again, we worked on what he did not understand. He did hear all the words. However, he needed to say “I don’t know what a stewardess is,” or, “I don’t know what that word means.”

When he is in first grade and the teacher asks this question to the class, she might say, “Where do you think the passenger was?” The child above guessed and said, “In the kitchen.” He heard dinner and he did the strategy of word webs and what goes with it. That was not so bad, but it was the wrong answer. Then the teacher would think that he has no understanding of the concept. Children need to learn what the breakdowns are and to be able to advocate for themselves. We need to teach them to be more specific about what it is they need.

Sabotage

Sabotage is another strategy. I like to use sabotage because it is something that is fun. It keeps it playful with the children. There are two ways to do this. You create a problem or a mistake to block the goal of the child. You know what they want, so you put up a barrier or block so the child has to communicate to you. The easiest example is bubbles. The child wants to play with bubbles, so you screw the lid on really tight and give it to the child. The child cannot get the bubbles out of the bubble jar. Now you have created a situation where the child has to communicate. That is our goal.

We want children to not only develop listening skills, but also some expressive skills. You may have a child with autism and hearing loss, and you are trying to get joint attention and communicative intent. Maybe you start with the child looking at you and handing the bubbles back to you. That is communicative intent. Maybe the child has the communicative intent, but we are trying to get some vocalization that they hand them back to you. They have to say “more”, “help”, or “please.”

The other opportunity for sabotage is where you make the mistake and you give the child the opportunity to identify and correct it. This can show that you are not perfect and sometimes you are wrong. Sometimes I will purposely be wrong and the child will find that funny, or I am looking to see if they can pick it out. If we were putting animal puzzle pieces away, I might tell the child to put away the elephant, and I am going to put away the zebra. Next I tell him to put away the tiger, and now there is only an alligator left, and it is my turn. I say, “I am going to put away the giraffe,” and I pick up the alligator. I have sabotaged and am waiting to see if the child understood. They may catch it. Sabotage can be a bit fun in that way.

The only thing I would say about sabotage is to be careful. I have one colleague who feels it is overused, which it can be. You have to make sure that the child is solid in their vocabulary and the knowledge of what is going on. If the child really did not know the vocabulary of jungle animals, it could be confusing. I would only do this if I knew that the child knew the difference between a giraffe and an alligator. Then I am looking to see if they are paying attention and listening.

Listening First

Listening first was already mentioned with the auditory sandwich. I use the rule of threes. Say it three times, and if they do not understand it, let’s help them make that connection to understanding with a gesture or cue.

Favorable Listening Environments

To create favorable listening environments, keep the noise level down. I always counsel parents about this. When they are at home and playing with the child, they should turn the TV off. Close the windows. Do not sit next to the window air conditioning unit. Think about the noise levels and keep them down.

Auditory Feedback Loop

The auditory feedback loop is getting the child to listen to hear it, process it, and then say it. This develops the listening so that it is literally not going in one ear and out the other. Let’s try to get it in the ear, rattle it around in the brain and process it, then be able to repeat it.

My Voice Matters

My voice matters is expressive. We want to encourage children to start using their voice and develop expressive language. If they first say, “Oo”, I will say, “Yes you want some juice. Let’s go get you some juice.” Here we have done extension, and then we can do a little bit of expanding by saying, “More juice,” and trying to get them to put some words together. They may say, “Juice please,” and you say, “I want juice please.” Now you have corrected it grammatically. Encourage them to use their voice, as it is powerful.

Choices

Giving choices is another strategy. It is much easier when talking about closed set and open set, to say, “Can you get me the cat?” and there is a choice between a cat and a dog, rather than there being 25 different little animals to choose from. Start by making it easier. We want to start simple and then make it progressively harder for the child. We want them to feel successful. Do not make it overly challenging to begin with.

Build Auditory Memory

Building auditory memory is very important. To me, the three things you or parents can do are talk, talk, talk, build vocabulary, and build auditory memory. It is important for language development. Exposing them to music, songs, and nursery rhymes is important for learning to read later on. Using books for literacy development is important as well. Expose them to books from a young age. You can use them for vocabulary, language, and even speech production.

Auditory Hierarchy

At what level of skill is the child? I use Lev Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development as a guide. We have to be in the child’s zone, which means we have to be teaching a child at a level where they can learn. If we are too high, they will not understand, get frustrated and shut down. If we are at too low of a level, they will be bored and they will not increase their learning.

Let’s say I am just beginning to learn Russian and someone starts telling me a story in Russian. How much will I get out of that story and how much do you think I will learn? Nothing! I may be able to pick out one or two simple words if they said them slow enough, but I will have no idea what they were talking about. Let’s say I have learned some basic skills in Russian and someone comes to me and says, “nyet.” I know they said the word no, but now I am not learning anything else, because it is at too low of a level. I need more stimulation than that. We need to be in the zone of proximal development where the child has some development of skill and mastery. Then we want to stimulate them to the next level of skill.

In the 1908s, Norm Erber coined the auditory hierarchy of detection, discrimination, identification, and comprehension. Adeline McClatchie and I put together a book along these lines (2003), which added in some of the goals that go along with it.

Detection

Detection is where the child shows awareness of speech or sound. They detect it, but they are not going to understand what it means. They just know that the sound is present. Some of the goals that would go along with that would be having awareness of voicing, environmental sounds, Ling sounds, and then voice and distraction.

When we are working with children, we teach them when it is quiet. Then we can have them be a little more distracted with a puzzle or task and see if they will turn to sound at that point. Now they know that they hear something; they may not know exactly what it means yet, but they know that someone is there and will look to them.

Strategies. One strategy is rephrasing. If you are working with a young child to respond to the Ling sounds and are sitting off to the side so they will do a head turn response, you want to know if they are hearing sound. I do “ah” and the child does not turn. I can rephrase that by duplicating it three times like “ah, ah, ah” or I can add more intonation like, “ahahahaha.” I have given it more acoustic information to see if that will grab the child’s attention. This is a strategy we can use during detection.

Discrimination

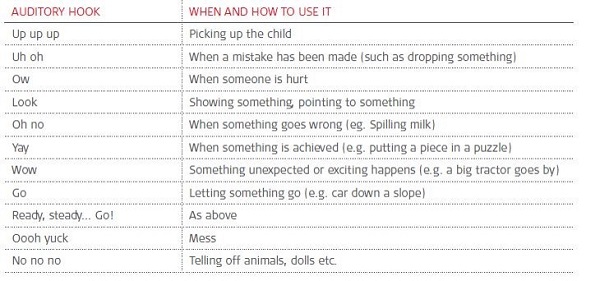

Discrimination is all the suprasegmental cues, duration, intensity pitch, and stress. Can they start to recognize that sounds are different? Is the sound short or long? Was it a soft sound or a loud sound? This is where we are starting to use the auditory hooks (Figure 1) and learning-to-listen sounds, motherese or sing-song voice. Grab the child’s attention. They are aware of sound, so now let’s use some familiar words or phrases with a lot of intonation differences. They will start to attach some meaning to it. We do this with typical children such as. “Up, up, up,” or “let’s go doooowwwwnnn.” All of that will give the child more acoustic information to attach to the object or the action, and hopefully they will start attaching meaning to the words.

Figure 1. Examples of auditory hooks.

Use vocal length differences, like long sound versus short sound. When you are doing an activity where they can be pushing a car, you say, “Goooooooo. Stop.” We do not necessarily want to do “Goooooo. Stop,” with a 14-year-old, but we might do family member names like Bob versus Elizabeth. Work on low pitch and high pitch, and then prosody. Auditory hooks come in at this level where they start to hear that acoustic word or phrase in a familiar routine.

Every time it is time for the child to go to bed I tell them to say something like, “Shhh. Night-night time.” If you are changing what you say every night, it will be harder for the child to attach the meaning to it. However, if you are consistent, they will start to learn that every time they hear, “Shhh. Night-night time,” it is time to go to the bedroom, put their pajamas on, and go to bed. They will start to make that association.

Strategies. Some of the different strategies you can use for the discrimination are shown in Figure 2. We definitely want to use greater acoustic contrast. This is the level where you are providing them with an abundance of acoustic information and using choices.

Figure 2. Strategies for discrimination.

Purposeful Play

Let me give an example of purposeful play. We have a baby doll, a toothbrush, a cookie, a spoon, a bowl, and washcloth. If you say, “Let’s brush your teeth. Where is the toothbrush? Where is the cookie?” There is not a lot of auditory discrimination difference. It is better to do things like, “mmmm” for the cookie and “Brush, brush, brush” for the toothbrush, because that is more acoustic information for the child to grab, rather than “toothbrush” or “cookie.”

In purposeful play, we talk to the parent first about what level we are working on. Our goal is to discriminate between routine utterances that differ by intonation and rhythm. Some examples of target words that you can use are: mmm; brush, brush, brush; shh, go night-night; num num num. That gives them more of an idea of what to work on at home with their child rather than saying, “Let’s feed the baby with the spoon” or, “Let’s brush her teeth. Where’s the toothbrush?” We make it a little bit simpler, and as they build their language, we will move to the next level.

Identification

Identification is where the child starts to understand and build vocabulary so we do not have to use as much of the motherese or suprasegmental differences. They understand simple words, phrases and sentences along with building a memory. Now you can say, “Give me the cookie and the toothbrush and the spoon,” because that is the auditory memory. To build vocabulary, we tier it based on complexity, such as Tier I, II, and III. Tier I might be cat or tiger, and the next tier might be feline. We go from easy to more complex vocabulary.

The second goal of identification is auditory memory. In the beginning, the number of things we may include in a statement are few. For example, in the beginning we might say something with one key word like, “Go get your shoes.” Then we would move to, “Go get your shoes and give them to Daddy.” Then you would move up to three or four key words. We are increasing the number of key words they are listening for. That is auditory memory.

We are also looking at the length of the utterance from a short phrase such as, “Color the eyes on the duck yellow,” to, “Find the dog walking across the bridge, and color his eyes blue. The key words are still the eyes, animal and color, but we want them to start to listen to some of that throwaway language. Auditory memory is important to language acquisition. Some of the different strategies that you can use at this level are auditory sandwiches and adding sabotage.

Examples of purposeful play are the farm animals, and our level is identification. Our goal is to build receptive vocabulary. We will do the animal names, but do not get stuck on those. Start to think about other things like parts of the animals such as nose, eyes, mouth, and also action words like run, jump, and sleep. Think about adjectives and adverbs such as big, little, slow, fast. Many times it is easy to get stuck on labels and nouns. You want to make sure that you are expanding that child’s vocabulary.

For auditory memory, try a tea party if you are on the level of identification. Our goal is to increase the ability to follow direction with two to three key words. Have five or six different food objects out. The directions could be, “Give the cookie and the apple to Grandma,” which has three key words, smaller sentence direction, and a closed set. Eventually we want to build the key words into a longer open-set sentence as they develop skills.

Comprehension

Last is comprehension. Now they can understand longer and more complex spoken language. They have built their vocabulary and auditory memory. They have what we call surface structure language. Now we are working on answering questions, using thinking skills, and engaging in conversation.

Some of the different goals at this level are (a) advanced vocabulary development, not only concrete vocabulary, but more abstract such as while, until, so and therefore. There are no pictures for these words.

We want to build what is age appropriate, doing (b) word play associations like the Word Webs. Not only do they understand that it is an apple, but that it is a fruit, it is red, it is round, it grows on trees, you eat it, it has seeds, and it has a stem. It is all about building vocabulary.

We also want to work on (c) understanding more advanced language that they have to think about. It is not just identification but more information; the message is not always straightforward. Before we would have said, “Color the eyes on the dog blue.” But at this stage we would say something like, “Find an animal that lives on the farm and color its eyes blue.” There is more processing that has to take place.

Another goal is (d) chunking information. One example would be listening to a story that has sequences, such as, “The boy is going to go outside and climb the tree. After he climbs the tree, he will go down to the lake and sail in the boat. Then he will come back and play cards with his grandpa.” You may have pictures, and the child has to put them in the order that he heard the story. This requires listening to longer pieces of information, chunking it together, retaining it, and recalling it with auditory memory.

An additional goal is (e) answering simple to more complex questions along with listening to shorter and then longer paragraphs of information. With a five-year-old, you will keep it short and concrete. You can do it with a 15-year-old, but it is longer and there is abstract information involved. The goal is the same, however. It is the stimulus or the length of sentence that you are using that will change depending upon the child’s age and skills. Increasing their thinking skills and cognitive language, following conversation with a known topic, then being able to follow a conversation with an unknown topic are all the higher level auditory skills that we want to have children develop.

Cognitive Language Skills

Specific cognitive language goals or thinking goals include (1) inferencing which is not straightforward information. Another is (2) interpreting and paraphrasing or having the child retell you a story. They may have great auditory memory, but can they use different vocabulary and come back with a story? Another goal is (3) problem solving. Can they do math word problems such as, “Jane has three fewer marbles than Johnnie, and Johnnie has five. How many marbles does Jane have?” There is language there. Children can do well with the computation if you tell them what 5 – 3 is, but if you word it in that kind of word problem, do they understand less means that you have to use minus? Our children with hearing loss can get stuck with word problems in math.

We can work on (4) identifying missing information. I have a bowl and an ice cream container, and I want to have some ice cream. What am I missing? What do I need? It is the spoon. Can they think of that themselves?

Another skill is (5) defining and explaining. We know that children with hearing loss have difficulty with multiple definitions, and we want to work on that. Additional goals are: (6) cause and effect; (7) predicting; and (8) listening to stories, picking out the main ideas, the sporting ideas, the sequence, and the conclusion. They can tell you the details in the story, but can they tell you the sequence, what the story was about or the conclusion?

A fun goal is (9) humor, which is important in language. We want to make sure that they understand knock-knock jokes at a young age, that school children understand word plays, and older children can recognize sarcasm, because that has to do a lot with intonation. A word play example is “Why did the farmer call his pet pig ink? Because he kept running out of the pen.” Can a child understand why that can be funny? In addition to that, (10) figurative language, idioms and metaphors are important to teach as well.

Strategies for Comprehension

There are many different strategies that you can attempt. You may have to repeat information, acoustically highlight, rephrase to a simpler level such as “Mary is ill today. Where do you think she went?” The child does not understand that so you say, “Mary is sick. Where do you think she has gone?” The child may know the word “sick,” so ill must be the same as sick.

An example of the purposeful play could be telling the parent that the child needs to work on some inferencing skills. They need to go home and work with the dollhouse. What do they do? Help them by giving them the level at which you are working. In this case, it will be comprehension. The goal is to start to get the child to infer from information provided. Instead of saying, “Put the boy in the car,” or, “Make mommy go into the kitchen and make dinner,” inferencing would be more like, “The little boy is hungry. What should he do?” or, “What is something that has wheels and windows and you drive it?” Now they are learning how to input more thinking into the play, rather than just identification.

Conclusion

As we conclude, you should have a better understanding of some of the play milestones, auditory strategies that you can use to facilitate listening and the spoken language, what the auditory hierarchy is, and different goals that you can use within each level to develop those skills. We discussed how to set up a purposeful play activity that specifically targets the listening goal.

For early interventionists, Med El has the Little Ears diary activity for you if you are thinking about some play activities that you can do, or you can give it to parents to help guide an activity. This is a free download that you can get from our website, www.medel.com. It gives you six months’ planning, a weekly lesson, and a play activity to use to facilitate listening development. It is a helpful guide that will walk you through this process. There is much purposeful play involved in that, and if you know the auditory levels and the auditory strategies to use, then you have the different activities outlined for you.

Reference

Erber, N.P. (1982). Auditory training. Washington DC: AG Bell Association for the Deaf.

Cite this Content as:

Therres, M. (2015, October). Auditory development series: Auditory development hierarchy. AudiologyOnline, Article 15458. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.