Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Discuss the use of the Hearing Aid Skills and Inventory (HASK) checklist.

- Explain how to assess a wearer’s digital literacy.

- List the Stages of Change model and how it affects follow-up care.

Introduction

Part 1 of this article reviewed three studies that demonstrate the unpredictable nature of follow-up care and the vital need for the hearing care provider throughout the rehabilitation process. In Part 2, we examine how AI-driven features in new generation hearing aids when combined with targeted person-centered counseling and other systematic approaches to follow-up care can speed the wearer’s journey toward consistent, full-time use of their devices.

Empowering vs. Helping

At first glance, helping and empowering are one in the same. After all, Audiology, a “helping profession,” both helps and empowers persons with hearing loss. Although it is a perfectly acceptable term, one used to describe dozens of fields, being part of a helping profession implies the hearing care professional is providing assistance or support; tasks which are largely passive in nature and tend to create dependence on the professional. In contrast, to empower someone means you are providing the knowledge, skills, tools and resources needed to be self-sufficient. Upon second glance, perhaps there is a big difference between empowering and helping a person with hearing loss. To empower is to give someone more confidence or strength to independently complete a task or change a maladaptive behavior. Helping of course might be beneficial, but empowering is more effective.

Here we argue that the primary purpose of follow-up care is to empower each patient so that he or she becomes a consistent, full-time hearing aid wearer. The benefits of hearing aid use largely stem from the wearer’s ability to fully commit to consistent, full-time use. Steady, regular use occurs only after individuals have obtained the necessary skills and knowledge, often with direct involvement from a hearing care provider (HCP) who has empowered the wearer. It is during these periodic post-fitting follow-up care visits, where HCPs identify and address gaps in the individual wearer’s skills or knowledge, that the path toward steady, regular use is established.

Rather than passively helping persons with hearing loss acclimate to their hearing aids, a primary goal of should be empowering individuals to master the skills needed to be successful hearing aid wearers. Besides improving the ability to communicate more effectively in all daily listening situations, we believe there are three commonsense reasons a primary goal of follow-up care is to promote consistent, full-time hearing aid use and to empower wearers master the skills and knowledge needed to reach this goal.

Reason 1, Quality of Life Improvements Stemming from Full Time Use

Over the past decade, there have been myriad observational studies suggesting hearing aid use directly contributes to better overall quality-of-life. Among the many quality-of-life factors believed to be affected by hearing aid use are improved physical activity (e.g., Martinez-Amezcua et al, 2021) a slowing of cognitive decline (e.g., Gando, et al, 2023), and increased levels of social activity (e.g., Holman, et al, 2021). In one example, Campos et al (2023) compiled survey data from 299 adult hearing aid wearers. Their analysis found a 50% reduction in the odds of experiencing a fall for hearing aid users compared with non-users. Their findings suggest that the use of hearing aids—especially consistent hearing aid use—is associated with lower odds of experiencing a fall.

Another example can be found in the recently published ACHIEVE study, the first randomized controlled trial to evaluate the potential for treating hearing loss stemming from cognitive decline (Lin et al, 2023). The study followed 977 participants, aged 70-84 with untreated hearing loss and limited cognitive decline over three years. Participants were recruited from two sources: 1) existing participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities ("ARIC") study, an ongoing study of cardiovascular health with participants initially recruited in 1987-89, and 2) de novo community volunteers. Participants from the ARIC study had higher levels of diabetes, hypertension, and were more likely to live alone. Each participant was assigned either to a hearing loss treatment group or a health education control group. They were followed for three years and assessed on thinking ability and memory skills. In the higher-risk population (ARIC group), the study showed that participants in the hearing aid treatment group had a 48% reduction in cognitive decline. Those participants who did experience a significant slowing of cognitive decline had high adherence (i.e., regularly wore hearing aids every day) to the hearing intervention over the 3-year study period.

These studies, which indicate hearing aid use improves various facets of quality of life, have one commonality: the study participants who experienced significant improvements tended to wear their hearing aids several hours per day, every day.

Reason 2, Leverage Brain Plasticity

Crossmodal plasticity is a fast, dynamic process which describes the brain’s ability to reorganize itself based on use. In simple terms, crossmodal reorganization occurs when sound is not stimulating the auditory cortex and other senses “take over” that region of the brain. Research has demonstrated that crosssmodal reorganization occurs even in individuals with mild hearing loss, it can appear within three months of hearing loss onset, and importantly, and it can be reversed with as little as six months of hearing aid use. (see Kral & Sharma, 2023 for a review of crossmodal plasticity in hearing loss). Further, Sharma (2021) presented neuroimaging evidence from long-term hearing aid users who were ‘underfit’ that showed crossmodal reorganization even after extended periods of hearing aid use, suggesting correctly fitted hearing aids are important for providing the necessary gain to the auditory cortex to reverse cross-modal changes. Although “correctly fitted” implies matching a validated prescription target and verifying that match with probe microphone measurements, we argue that another essential but oft-forgotten component of “correctly fitted” is consistent, full-time use. That is, matching a target to ensure sounds are audible to the wearer is a one-time thing, but regularly wearing hearing aids fitted to those targets is an everyday task - one likely to lead to improved outcomes.

Reason 3, Beyond Good, Better, Best Technology Tiers

A final consideration that possibly hinders the effectiveness of follow-up care is that higher levels of hearing aid technology are often equated with greater levels of wearer success. That is, it is believed by many HCPS that fitting a higher level of technology will automatically increase the chances of the wearer being more successful, because, well, it’s premium technology. Although it is tempting to believe premium technology leads to better outcomes compared to lesser levels of technology, several studies indicate that for both laboratory and real-world measures there is not a significant difference in outcomes between basic and premium technology tiers. (See Plyler 2023 for a review of the research comparing premium to basic technology levels in hearing aids).

The findings from these studies comparing wearer outcomes from basic and premium technology tiers suggest that successful outcomes are primarily dependent on hearing aid use itself. Since both basic and premium technology tiers, 1.) restore audibility by frequency shaping to match targets for soft, average and loud input levels, 2.) accommodate the wearer’s dynamic range by keeping the device’s maximum output under the wearer’s loudness discomfort level, and 3.) provide sufficient noise management strategies, perhaps the most critical aspect of success is not the technology tier of each wearer, but his or her ability to adeptly manage their devices using skills and knowledge acquired during periodic follow-up visits.

Notwithstanding reason 3 above, it is important to note there is ample evidence suggesting individuals who 1.) struggle in background noise, as measured by the Acceptable Noise Level (ANL) test (Plyler et al 2021), 2.) self-report they are in high demand listening situations (Hausladen et al 2022), or 3.) report that they like using smartphone-based apps for direct streaming and manual control of their hearing aids (Saleh et al 2022) tend to prefer premium-level hearing aid technology. These findings are all compelling arguments for recommending premium-level technology. Our point, germane to follow-up care, is that the mere act of recommending and wearing premium technology, alone, is not enough to yield more favorable outcomes. An empowered wearer trumps the technology level of their hearing aids.

New Generation Hearing Aids

Now we turn our attention to how features found in new generation hearing aids can be used to more efficiently address common wearer-related problems that impede consistent hearing aid use. New generation hearing aids are believed to contribute to the remarkable quality of life improvements, recently documented in MarkeTrak 2022 (Taylor and Jensen, 2023). Additionally, as this next section shows, these features can play a critical role in the follow-up process.

Until recently, hearing aids and consumer electronic devices existed as completely separate product categories. However, everything began to change when the first hearing aids with direct Bluetooth streaming became commercially available in 2014. As illustrated in Figure 1, a broad range of technology, historically confined to consumer electronic devices, has swiftly found its way into prescription hearing aids. In addition to the features listed in the consumer electronics box in Figure 1, new generation hearing aids have several unique features not found in traditional hearing aids, including AI-driven fine-tuning, activity tracking and remote fitting. Each of these features, unique to new generation hearing aids can be deployed during the follow-up process to solve common problems that get in the way of consistent, full-time hearing aid use.

Figure 1. The convergence of features found in consumer electronic devices (right box) with the standard features found in many traditional prescription hearing aids (left box) is now a new generation of hearing aids offering new possibilities for the wearers (center box). These are some of the new generation features considered to be an integral part of follow-up care that can be used to promote better daily usage of hearing aids.

Recall in Part 1 the three leading causes of hearing aid non-use were handling ability, sound quality and a lack of perceived wearer need (Solheim et al 2018). Next, we discuss how features unique to new generation hearing aids can be used to address these common problems that hinder regular, full-time hearing aid use.

AI-driven Fine-tuning

Artificial intelligence (AI) is not new to hearing aids. One common type of AI found in most modern hearing aids is neural networks, embedded in the hearing aid’s signal classification system. These types of neural networks are trained in the lab by engineers to automatically recognize acoustic patterns in the wearer’s soundscape. In this application of neural networks, the input signal to the hearing aid is amplified differently, depending on if the neural network “recognizes” the wearer’s soundscape to be primarily speech, primarily noise or music. Another application of neural networks in hearing aids is to use them in the fine-tuning process.

More than 25 years ago, hearing aids evolved from a screwdriver to computer-based fitting software to make adjustments. However, the methods used to fine-tune and adjust hearing aids in the clinic during routine follow-up appointments have not changed: Clinicians still mainly rely on wearer feedback during an in-person appointment to change and modify the acoustic parameters of the devices to address issues related to sound quality.

As previously described in Part 1, follow-up visits involving fine-tuning are common (Tecca, 2018), and most HCPs would agree, time consuming. Additionally, the fine tuning decision-making process of clinicians tends to vary (Anderson et al., 2018) and for good reason: Wearers cannot always find the language to describe sound or accurately recall situations where they had problems hearing. During follow-up appointments this means HCPs must make educated guesses about what might fix the problem—in the perfectly quiet clinic—before sending the wearer home for another trial round in real-world listening situations.

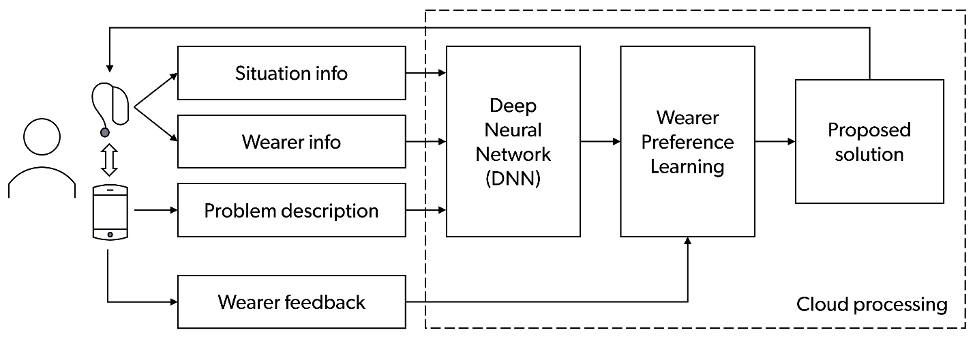

Launched in late 2019, Signia Assistant uses machine learning to predict the hearing aid adjustment that best addresses a problem experienced and reported by the wearer. Signia Assistant is powered by a live deep neural network which is capable of being fed anonymized data of user preferences. Signia Assistant is connected to the wearers’ hearing aids using a smartphone-enabled application (app). Figure 2 is a schematic of Signia Assistant. Effective use of Signia Assistant requires wearers possess a smartphone and demonstrate that they can use it proficiently. Using a structured approach and a simple user interface, Signia Assistant enables wearers to report specific problems and then applies machine learning to suggest an adjustment of the hearing aids that the wearer then could choose to keep (or reject) in their hearing aids. This process can be completed independently by the wearer once the HCP has instructed him on how Signia Assistant works.

Figure 2. Simplified diagram showing the main elements and functionality of Signia Assistant. The DNN and Wearer Preference Learning are running in the cloud. All data sent to the cloud are fully anonymized.

Signia Assistant learns the listening preferences of wearers and is thereby enabled to suggest more precise real-time adjustments that lead to higher acceptance rates (Jensen et al 2023). As Signia Assistant’s neural network gathers more information, it can make better predictions of individual wearer’s fine-tuning solutions. Additionally, as Signia Assistant’s live deep neural network gathers more information from wearers, the types of solutions offered the wearer change. This demonstrates how the neural network on-board Signia Assistant continually improves the possible solutions it provides wearers. For these reasons, the ability for wearers to fine-tune their own hearing aids is an efficient way to reduce the number of follow-up appointments where the HCP must conduct time-consuming fine-tuning. Additionally, all changes made by the wearer using Signia Assistant are made available to the HCP through the Connexx fitting software. This allows the HCP to know what fine-tuning adjustments were made by the wearer and facilitates further follow-up counseling.

App-based Handling Instructions

An added benefit of Signia Assistant is that several short instructional videos are embedded into this feature. When the wearer opens the Signia Assistant app, they are asked if they are having difficulty handling the hearing aids. If wearers are having problems handling their devices, they are asked what type of handling problem it might be: maintenance, usage, accessories or troubleshooting. Depending on the problem specified by the wearer, the Signia Assistant will play a short video that demonstrates the skill needed to successfully handle the devices for the specific form factor used by the wearer. Considering that an inability to properly handle hearing aids is the second leading contributor to non-use (Solheim et al 2018), it is helpful to make self-instruction available through the Signia Assistant app for the smartphone-savvy wearer.

AI-Driven Service and Support

Although not yet available in new generation hearing aids, a recent development using artificial intelligence (AI) are chatbots. Chatbots are trained using vast amounts of text from the internet and fed into systems that predict the most likely response to a question posed to it. In identifying these patterns in the text, the chatbot learns to generate new language on its own. Perhaps the best example of this application of AI is ChatGPT (Goodman, et al 2023). However, chatbots are just beginning to be used in healthcare for routine tasks such as treatment support and health monitoring (Milne-Ives, et al 2020), and Swanepoel et al (2023) review several future applications of chatbots in hearing health that will be useful for a variety of routine clinical tasks.

Unlike the human HCP, a chatbot is always a click away from providing advice, service and support. However, as good as chatbots might be at using enormous amounts of information to make coherent, predictable responses to common queries, they lack many human qualities. Although AI-driven hearing aid features and chatbots will likely replace the HCP for certain tasks, there are an abundance of problems, addressed during follow-up visits, that put wearers at-risk for non-use. These problems, outlined below require common sense reasoning, sound clinical judgment, and the ability to clearly communicate with help seeking individuals – a combination of skills known as counseling.

Counseling to Address Problems with Perceived Need

When AI-driven and app-based hearing aid features of new generation hearing aids are placed into the hands of the wearer, they have the potential to address two of the most common problems that contribute to multiple follow-up visits and non-use of hearing aids: Sound quality and handling.

In contrast, the third common problem that often leads to non-use is the wearer’s lack of perceived need. Experienced HCPs know that when wearers believe they don’t really need hearing aids, they are more likely to give up and stop wearing them when they encounter problems. The problem of perceived need is complex and likely reveals wearers perceive the total costs of committing to wearing devices are greater than the benefits they will obtain (Ng & Loke, 2015). To fully illustrate this cost/benefit calculation among wearers, let’s use an example.

During the hearing aid evaluation and fitting appointment, a wearer agrees to acquire hearing aids, perhaps to placate a spouse or to please their grandchildren, but during their initial experience, when they encounter a problem, they quickly abandon the devices. The problem becomes in essence an obstacle, or even an excuse for the devices ending up in a drawer. Because the individual has failed to take ownership of their condition or is not empowered to confidently address any obstacles getting in the way of successful use, they easily throw in the towel and give up. Wearer problems related to perceived need (e.g., “I don’t need hearing aids.”) reflects that many individuals acquiesce to acquiring hearing aids but have failed to reach the action stage of change.

Hearing care providers understand that not all persons with hearing loss who attend an initial help seeking appointment go on to obtain hearing aids, and even those who do acquire hearing aids might not be ready to learn and sustain the behaviors to be successful wearers over the long haul. Simply because a person is fitted with hearing aids doesn’t mean they have internalized the need to use them. Wearers need to have a strong internal belief that they have agency over their condition, even after they have had hearing aids for several months. If wearers do not yet feel ready to use hearing aids and acquire all the skills and knowledge to use them effectively, they are unlikely to have much long-term success integrating them into their daily life. Consequently, HCPs must try to gauge how ready wearers are to improve their hearing --- even long after they have acquired hearing aids. Follow-up appointments are the ideal time to gauge their ability to acquire and maintain the skills and knowledge to be successful.

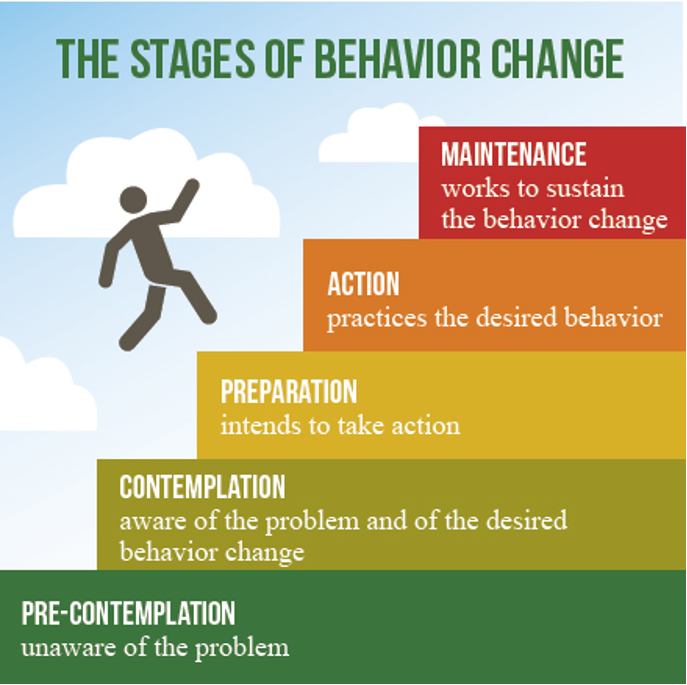

The Stages of Change model is a health behavior change model that can be useful for HCPs to explore wearers’ readiness for change (Manchaiah, et al, 2018). (The change we are referring to is the wearer’s ability to make the necessary changes in habits and routines that allow for daily hearing aid use.) The Stages of Change model serves as a useful framework for understanding how the person with hearing loss perceives their condition – even after being fitted with hearing aids. The Stages of Change model views behavioral change as a process that occurs along 5 key stages: (1) pre-contemplation (problem denial or lack of awareness); (2) contemplation (awareness of problem); (3) preparation (intention to change behavior); (4) action (overt behavior modification); and (5) maintenance (sustained behavior change). The model suggests that individuals who are in the later stages of change are more likely to succeed at help-seeking, intervention uptake, and adherence. Figure 3 summarizes these five key steps.

While it is mainly applied to the initial help seeking appointment, the Stages of Change model also can be used during the follow-up process by defining the skills and behaviors needed by the wearer to be a successful wearer. Many of the skills and behaviors that lead to successful use include:

- An internal belief that hearing aids are beneficial and contribute to the wearer’s overall well-being.

- Recognize the link between consistent hearing aid use and improved participation in daily activities that matter most to the wearer.

- Ability to wear the devices all day. This requires ability to insert/remove from ear, charge or change battery, adjust the devices with on-board control, remote control of smartphone app.

- Ability to recognize when a specific feature needs to be activated and then knowing how to make the proper activation.

- Situate themselves in the proper place in acoustically challenging situations in order to maximize benefit.

Figure 3. The five landmark behaviors associated with the Stage of Change model. Image published with permission of Audiology Practices, a quarterly journal of the Academy of Doctors of Audiology.

Recall from Part 1, according to Solheim et al (2018), 43% of non-wearers reported that a lack of “perceived need” contributed to their non-use. To uncover problems associated with a lack of perceived need, and to ensure that the essential thoughts and beliefs that lead to successful use are being instilled in the wearing during follow-up appointments, HCPs can employ these techniques, summarized by Greenness, et al. (2015):

- Be more flexible in the management phase of the appointment – focus more broadly on raising awareness of how hearing aids can positively impact daily activities.

- Invite a family member to attend appointments – having a family member within the appointment may help facilitate a broader discussion of the wearers’ potential hearing difficulties in everyday life and how these could be addressed.

- Individualize information provision and rehabilitation planning – provide information relevant to the wearer and meaningful rationales for change, without applying pressure.

- Focus more attention during follow-up visits on the individual and less on the hearing aids. After ensuring the devices are properly working, take the time to fully explore with the wearer why they believe they don’t need hearing aids or have stopped wearing them. Encourage the wearer to create a list of all the situations where communication is improved with the use of hearing aids.

- A person-centered approach to the decision-making process facilitates the building of a long-term relationship with their hearing care professional. Each follow-up visit is an opportunity to re-evaluate which stage of change the wearer might be in at that time, and to create goals that move the wearer back into the action or maintenance stage.

- To free up time in the clinic, provide added convenience to the wearer and provide more “touchpoints” between the HCP and wearer, consider using remote/virtual care options for some of these follow-up appointments.

- Ensure that any concerns that impede hearing aid use are addressed in a timely manner.

Towards More Engaging and Efficient Follow-up Visits

The purpose of follow up care is to improve the likelihood of steady, regular use for every wearer. More specifically, a key role of the HCP is to identify and fix any problem that creates an obstacle to consistent use of the hearing aids, as quickly and efficiently as possible. Given that many quality-of-life attributes stem from better hearing – which is more likely to occur through consistent, daily hearing aid use, it’s important to marshal a broad array of tools that accelerate and promote full-time use. These tools mayinclude AI-based algorithms (Signia Assistant) and person-centered counseling that uses the Stages of Change model as a foundation.

Hearing care providers know treatment is considered incomplete at the time of the fitting; instead, the initial fitting is simply the beginning of an on-going rehabilitation process that often requires the expertise and support of a professional. Providers also know that spending too much time with patients is an indicator for unsuccessful hearing aid use. Survey data from more than 3000 hearing aid owners (Kochkin et al 2010) suggested that more than three visits in the hearing aid acquisition process was strongly related to “below average” real-world outcomes. Further complicating matters, studies reviewed in Part 1 of this article indicated that roughly one-third of all hearing aid wearers need more than three follow-up visits to achieve success, often for fune-tuning.

An updated approach to follow-up care, one that empowers the wearer, does two important things: 1.) blends AI-driven features with person-centered counseling with the primary goal of instilling skills and knowledge that promote consistent daily hearing aid use, and 2.) starts during the initial help seeking and fitting appointments – well before the first follow-up visit is scheduled. We conclude this 2-part article by reviewing some recently introduced tools that help blend the high-tech world of AI-driven algorithms with the high-touch world of person-centered counseling. For HCPs interested in breathing new life into their follow-up process we recommend three tools. Each of the three tools mentioned below could be introduced during the initial fitting process and then re-visited during subsequent follow-up visits. All three tools are designed to promote empowerment of the individual wearer.

Evaluate Digital Literacy

New generation hearing aids implement features that require the use of a smartphone and apps. Since a smartphone is an essential part of their use, it is necessary for HCPs to carefully evaluate the smartphone handling skills of the prospective wearer prior to use of hearing aids. For wearers judged to have proficient digital literacy skills or those who display a willingness to learn them, there is an opportunity for these wearers to experience the benefits of AI-driven fine-tuning, app-based handling instructions and other features unique to new generation hearing aids.

Sucher, Sahoto & Ferguson (2022) developed the two-question Digital Literacy Questionnaire (DL2Q) to access the digital literacy skills of adults with hearing loss. They found that adults with hearing loss have different levels of digital literacy, with 63% of adults between the ages of 65 and 85 years of age judged to have “good” digital literacy. This finding presumes the majority of older adults can independently navigate smartphone apps integrated with their hearing aids.

The DL2Q is comprised of two questions:

A. How would you rate your skill level with a smartphone?

B. How confident are you in using a smartphone?

For Question A, using these multiple-choice options: never used, beginner, competent, if the wearer chooses “competent,” they are a good candidate for the smartphone being integrated with the hearing aids with minimal assistance from the HCP.

For Question B, using these multiple-choice options: not confident at all, I usually need help, it depends on the task, or I am confident, if the wearer chooses the latter two options, they are a good candidate for the smartphone being integrated with the hearing aids with minimal assistance from the HCP.

By administering the DL2Q, HCPs ensure access to many new generation hearing aid features that are integrated into smartphone-enabled apps is not withheld from those who might benefit from them. For example, a wearer who demonstrates proficient skills and confidence for smartphone use on the DL2Q could be encouraged to use Signia Assistant for independently fine-tuning their own devices. Moreover, if the DL2Q scores indicate that either skill level or confidence are low, it is an opportunity for the HCP to provide customized training during follow-up visits.

Systematic Assessment of the Wearer’s Skills and Knowledge

Although AI-driven features enable wearers to make their own fine-tuning adjustments or learn how to better handle their devices, they don’t have to be left completely on their own to do these things. In fact, there is solid evidence suggesting an individual’s ability to manage their hearing aids is associated with regular hearing aid use. Bertoli et al (2009) gathered survey data from more than 8,000 hearing aid wearers. They determined that “regular” hearing aid use was significantly associated with self-reported hearing aid management ability. Specifically, relative to individuals who reported very good hearing aid management ability, those reporting ‘‘rather good’’ management were 1.76 times as likely to be “nonregular” hearing aid wearers. Further, the odds of non-regular hearing aid use increased to 6.29 and 13.35 times, respectively, if individuals reported ‘‘rather bad’’ or ‘‘very bad’’ management skills.

Making matters worse, we know that hearing aid wearers tend to be rather inaccurate self-reporters of the hearing aid management skills (Doherty and Desjardins, 2012). For these reasons, it makes sense to formally assess the skills and knowledge needed to be a successful hearing aid wearer. Along with using apps, such as Signia’s MyWearTime to monitor daily use time, periodic follow-up visits are the ideal time to both formally assess and systematically improve skills and knowledge.

Two different questionnaires have been developed that can be administered to wearers during routine follow-up appointments that help the HCP target specific problems related to how hearing aids are handled and controlled by the wearer. Once these specific problems have been identified, the HCP can device a training strategy that enables the wearer to obtain the knowledge and skills needed to overcome the obstacle.

The Hearing Aid Skills and Knowledge Inventory (HASKI) was developed by Bennett et al (2018). Consisting of two versions, one self-administered and the other clinician-administered, the HASKI is another validated self-report that systematically evaluates 73 items related to use and handling using 14 questions.

The Hearing Aid Skills and Knowledge (HASK) was developed by Saunders, et al (2018). It is a 12-question self-report that targets several of the most salient aspects of handling of hearing aids. The HASK carefully delineates between knowledge and skills and enables the HCP to score the wearer’s ability to manage their devices. Given its brevity, we recommend use of the HASK to assess and improve the hearing aid management skills and knowledge of each wearer over the course of follow-up care. Table 1 lists the topics and skills the HASK assesses. For details on administering and scoring the HASK see the appendices of the Saunders et al (2018) article. Note that some of the topics and skills summarized in Table 1 may not apply to specific wearers. Similarly, skills related to direct streaming and use of rechargeable batteries could be added or substituted to the list in Table 1. As the authors suggest, the HASK can be easily adapted to meet the needs of a wearer with newer features such as wearer-controlled apps or AI-driven fine-tunings. By listing the essential skills needed to complete the task, and adding to a customizable version of the HASK, the HCP can quickly identify which skill is lacking, which skill the wearer might be unsure about, and which skills have been mastered.

Topic Area | Skills Tested |

Hearing aid removal | Remove from ear |

Open battery door | Knows how to turn hearing aid off. Opens battery door |

Selection of correct battery | Knows appropriate battery size/color Knows how to order new batteries |

Changing the hearing aid battery | Knows when to change battery (hearing aid dead or battery warning tone) Knows battery duration (4 days to 2 weeks) Removes old battery Removes battery tab Leaves battery aerate for at least one minute Inserts battery into aid |

Cleaning the hearing aids | Ear tip/sound bore (loop or wash) Microphone (with brush) Body of aid (with cloth) Knows how often to clean (daily to weekly) |

Knows left versus right | Know left versus right devices |

Inserts hearing aid into ear

| Inserts aid into right and left ear Body and canal tip/earmold are seated properly in the right and left ear

|

Volume increases | Able to increase volume |

Phone use | Switches to telephone program /t-coil switch (if appropriate) Places phone in correct relation to hearing aid |

Program use | Goes through programs (if appropriate)

|

Feedback troubleshooting | Checks hearing aid is seated properly |

Troubleshooting | Checks the battery door is closed Changes hearing aid battery Checks microphone for blockage Checks sound bore for blockage Changes wax trap (if appropriate) |

Hearing Aid Storage | Open battery door Place hearing aid in case or dry-aid kit |

Table 1. The HASK topic areas and skills tested. Adapted from Saunders et al (2018).

Addressing Psychosocial Concerns with AIMER

The diagnosis of hearing loss and the recommendation to wear hearing aids can be off-putting and jarring for some. Because of this, some individuals express psychosocial concerns regarding the use of hearing aids. These psychosocial concerns can take the form of strong negative reactions or indifference regarding the use of hearing aids. Examples of psychosocial concerns include expressions of frustration, embarrassment and avoidance surrounding the use of hearing aids, Ekberg et al. (2014), through a systematic analysis of conversations between persons with hearing loss and their HCP, found that when individuals expressed concerns about using hearing aids, these concerns were usually psychosocial in nature. They also determined that many of these concerns were not addressed by the HCP during the appointment and because they were not addressed, individuals persistently re-raised the concerns during subsequent follow-up visits. The authors went on to say that a more thorough exploration of the individual’s perspective and displays of empathy are effective strategies for addressing these psychosocial concerns. Of course, for many HCPs, not formally trained in person-centered counseling, these strategies can be challenging to implement.

One approach, recently introduced by Bennett et al. (2022), attempts to empower HCPs to deliver psychosocial support to individuals with hearing loss. Given how many of these psychosocial concerns tend to get re-raised during follow-up visits, we believe this approach is an effective way to identify concerns that thwart the consistent, full-time use of hearing aids. Further, recall in Part 1 that 54% of non-hearing aid wearers reported “they didn’t really need them” (Solheim, et al. 2018). We believe this relatively large group of non-wearers would benefit from an intervention that focuses on their psychosocial concerns surrounding hearing loss and hearing aid use.

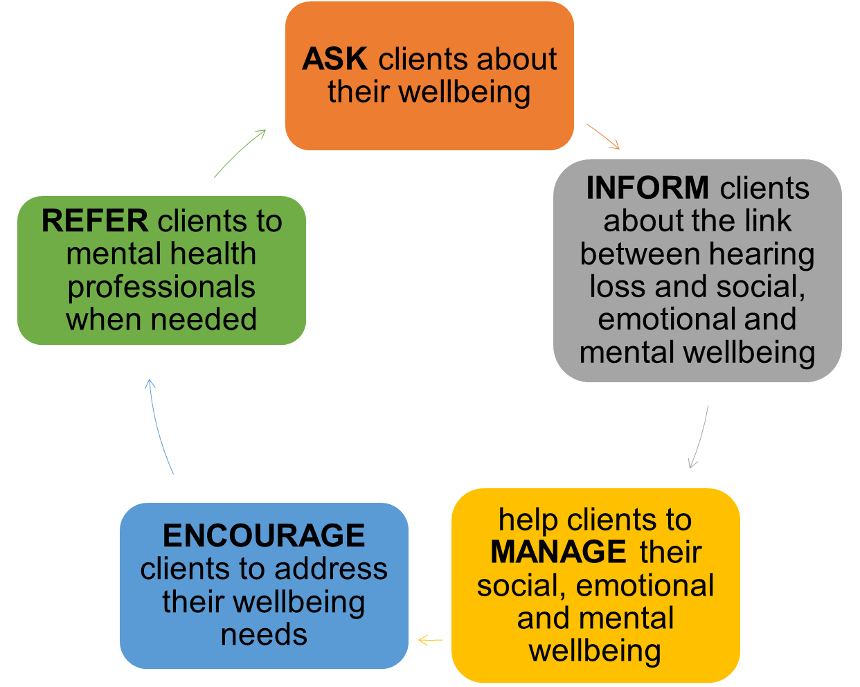

Bennett, et al. (2023) developed the AIMER program as a way for HCPs to identify and address these psychosocial concerns more easily. AIMER stands for Ask, Inform, Manage, Encourage and Refer. AIMER was developed to support HCPs with providing social and emotional well-being support in conjunction with their regular clinical care. It was tested over several months in a clinical setting where HCPs measured and observed how often social and emotional wellbeing was raised in appointments and how often they provided mental wellbeing support. Figure 4 is a summary of the five key steps of the AIMER approach. According to Bennett et al (2023), AIMER uses a variety of behavior change techniques to successfully improve the frequency with which HCPs: 1.) ask about, 2.) provide information on, and 3.) provide support for the mental well-being needs of adults with hearing loss. Given that psychosocial concerns often hinder hearing aid use, we believe, following some basic instruction on the concept, the AIMER approach should be used during any follow-up visit. To learn more about how AIMER can be implemented clinically, please see the September 2023 20Q from Bec Bennett, which can be accessed here.

Figure 4. A summary of the AIMER intervention created by Bennett and colleagues. Figure adapted from Bennett, et al 2023.

Summary

At its core, follow-up care is a golden opportunity to identify and fix any problems that hinder hearing aid benefit. However, we believe that not enough attention is paid to the follow-up process. Too often follow-up care is passive haphazard and incomplete. By evaluating digital literacy, assessing hearing aid management skills, and addressing psychosocial concerns, HCPs are in a better position to ensure that every wearer gets the most from their hearing aids. Because some wearers will always need more follow-up care than others, challenges are sure to remain. Fortunately, a combination of AI-based features that enable wearers to self-tune their devices and person-centered counseling approaches that can be easily implemented by any HCP, all wearers can get the care and attention they need to become successful.

Perhaps the irony of AI-based features found in new generation hearing aids is that as the technology becomes smarter, more automated and easier to use, it frees up precious clinical time for a deeper level of engagement between HCP and wearer. Engagement that results in greater empowerment of the individual.

References

Anderson, M.C., Arehart, K.H., & Souza, P.E. (2018). Survey of Current Practice in the Fitting and Fine-tuning of Common Signal-processing Features in Hearing Aids for Adults. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 29(2), 118-124.

Bennett, R., Meyer, C., Eikelboom, R., & Atlas, M.D. (2018). Evaluating Hearing Aid Management: Development of the Hearing Aid Skills and Knowledge Inventory (HASKI). American Journal of Audiology, 27(3), 333–348.

Bennett, R., Saulsman, L., Eikelboom, R., & Olaithe, M. (2022). Coping with the social challenges and emotional distress associated with hearing loss: A qualitative investigation using Leventhal’s self-regulation theory. International Journal of Audiology, 61(5), 353-364.

Bennett, R., Bucks, R.S., Saulsman, L., Pachana, N.A., Eikelboom, R.H., & Meyer, C.J. (2023). Use of the Behaviour Change Wheel to design an intervention to improve the provision of mental wellbeing support within the audiology setting. Implementation Science Communications, 4(1), 46.

Bertoli, S., Staehelin, K., Zemp, E., Schindler, C., Bodmer, D., & Probst, R. (2009). Survey on hearing aid use and satisfaction in Switzerland and their determinants. International Journal of Audiology, 48(4), 183–195.

Doherty, K.A., & Desjardins, J.L. (2012). The Practical Hearing Aids Skills Test-Revised. American Journal of Audiology, 21(1), 100–105.

Ekberg, K., Grenness, C., & Hickson, L. (2014). Addressing patients' psychosocial concerns regarding hearing aids within audiology appointments for older adults. American Journal of Audiology, 23(3), 337–350.

Ferguson, M., & Henshaw, H. (2015). Computer and Internet interventions to optimize listening and learning for people with hearing loss: Accessibility, use and adherence. American Journal of Audiology, 24(3), 338–343.

Ganbo, T., Sashida, J., & Saito, M. (2023). Evaluation of the Association Between Hearing Aids and Reduced Cognitive Decline in Older Adults with Hearing Impairment. Otology & Neurotology, 44(5), 425–431.

Goodman, R.S., Patrinely, J.R. Jr, Osterman, T., Wheless, L., & Johnson, D.B. (2023). On the cusp: Considering the impact of artificial intelligence language models in healthcare. Medicine, 4(3), 139-140.

Grenness, C., Hickson, L., Laplante-Lévesque, A., Meyer, C., & Davidson, B. (2015). The nature of communication throughout diagnosis and management planning in initial audiologic rehabilitation consultations. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 26, 36–50.

Hausladen, J., Plyler, P. N., Clausen, B., Fincher, A., Norris, S., & Russell, T. (2022). Effect of hearing aid technology level on new hearing aid users. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 33(3), 149-157.

Holman, J. A., Drummond, A., & Naylor, G. (2021). Hearing Aids Reduce Daily-Life Fatigue and Increase Social Activity: A Longitudinal Study. Trends in Hearing, 25, 23312165211052786.

Jensen, N.S., Taylor, B., & Muller, M. (2023). AI-based fine-tuning: how Signia Assistant improves wearer acceptance rates. Audiology Online. Available at: https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/ai-based-fine-tuning-signia-28555

Kochkin, S., Beck, D.L., Christensen, L.A., et al. (2010). MarkeTrak VIII: The impact of the hearing healthcare professional on hearing aid user success. Hearing Review, 17(4), 12-34.

Kral, A., & Sharma, A. (2023). Crossmodal plasticity in hearing loss. Trends in Neurosciences, 46(5), 377–393.

Lin, F.R., Pike, J.R., Albert, M.S., Arnold, M., Burgard, S., Chisolm, T., Couper, D., Deal, J.A., Goman, A.M., Glynn, N.W., Gmelin, T., Gravens-Mueller, L., Hayden, K.M., Huang, A.R., Knopman, D., Mitchell, C.M., Mosley, T., Pankow, J.S., Reed, N.S., Sanchez, V., … ACHIEVE Collaborative Research Group (2023). Hearing intervention versus health education control to reduce cognitive decline in older adults with hearing loss in the USA (ACHIEVE): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, S0140-6736(23)01406-X. Advance online publication.

Manchaiah, V., Hernandez, B.M., & Beck, D.L. (2018). Application of Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model in Studying Attitudes and Behaviors of Adults with Hearing Loss: A Descriptive Review. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 29(6), 548-560.

Martinez-Amezcua, P., Kuo, P.L., Reed, N.S., Simonsick, E.M., Agrawal, Y., Lin, F.R., Deal, J.A., Ferrucci, L., & Schrack, J.A. (2021). Association of Hearing Impairment With Higher-Level Physical Functioning and Walking Endurance: Results From the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 76(10), e290–e298.

Milne-Ives, M., de Cock, C., Lim, E., Shehadeh, M.H., de Pennington, N., Mole, G., Normando, E., & Meinert, E. (2020). The Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence Conversational Agents in Health Care: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(10), e20346.

Ng, J.H., & Loke, A.Y. (2015). Determinants of hearing-aid adoption and use among the elderly: a systematic review. International Journal of Audiology, 54(5), 291-300.

Plyler, P.N., Hausladen, J., Capps, M., & Cox, M.A. (2021). Effect of hearing aid technology level and individual characteristics on listener outcome measures. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(8), 3317-3329.

Plyler, P.N. (2023). 20Q: Hearing aid levels of technology—supporting research evidence? AudiologyOnline, Article 28462. Available at www.audiologyonline.com.

Ramachandran, V., Stach, B.A., & Schuette, A. (2012). Factors Influencing Wearer Utilization of Audiologic Treatment Following Hearing Aid Purchase. Hearing Review, 19(02), 18-29.

Saleh, H.K., Folkeard, P., Van Eeckhoutte, M., & Scollie, S. (2022). Premium versus entry-level hearing aids: using group concept mapping to investigate the drivers of preference. International Journal of Audiology, 61(12), 1003–1017.

Saunders, G.H., Morse-Fortier, C., McDermott, D.J., Vachhani, J.J., Grush, L.D., Griest, S., & Lewis, M.S. (2018). Description, Normative Data, and Utility of the Hearing Aid Skills and Knowledge Test. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 29(3), 233–242.

Solheim, J., Gay, C., & Hickson, L. (2018). Older adults’ experiences and issues with hearing aids in the first six months after hearing aid fitting. International Journal of Audiology, 57(1), 31-39.

Swanepoel, D.W., Manchaiah, V., & Wasmann, J.W. (2023). The Rise of AI Chatbots in Hearing Health Care. Hearing Journal, 76(4), 26, 30, 32.

Tecca, J.E. (2018). Are post-fitting follow-up visits not hearing aid best practices? Hearing Review, 25(4), 12-22.

Citation

Taylor, B. & Jensen, N. (2023). How AI-driven hearing aid features and fresh approaches to counseling can promote better outcomes: part 2, towards more empowered follow-up care. AudiologyOnline, Article 28727. www.audiologyonline.com