Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Discuss the average number of follow up care visits.

- Explain the type of problems that warrant follow up care visits.

- Define the components of follow up care.

Given the challenges persons with hearing loss face when adapting to hearing aids, treatment is not considered complete at the time of the fitting; instead, the initial fitting is simply the beginning of an on-going rehabilitation process. The purpose of this article is twofold: 1.) to review the number of follow-up visits and type of problems wearers are likely to experience during their first year of hearing aid use, and 2.) to explore how new generation hearing aids with AI-driven features, when combined with fresh approaches to person-centered counseling, are re-shaping the way follow-up care is delivered to hearing aid wearers.

Introduction

If you’ve been fitting hearing aids for more than a few months, you are already familiar with the following scenario. Let’s say Wearer 1 is fitted with hearing aids today and he schedules a routine follow-up appointment to see the audiologist in two weeks. Fitted on the same morning, Wearer 2 also schedules a routine follow-up appointment to be seen on the very same day in two weeks. Wearer 1 calls you a few days post-fitting, urgently needing some help, so you squeeze him in for a face-to-face appointment by the end of the week. Conversely, Wearer 2 keeps her scheduled follow-up appointment, reports great success and requires no additional scheduled visits. Two persons, fitted on the same day, with completely different follow-up experiences.

Based on this common scenario, it is easy to conclude that every person fitted with hearing aids has a uniquely different follow-up care experience. Some wearers diligently follow the regimen proposed by the audiologist, while others tend to cavalierly show up in the office or call you out of the blue when they have a more immediate concern. Further, some wearers need what seems like an infinite number of fine-tuning adjustments to their hearing aids, eating up precious hours of clinical time over the course of an entire year. In contrast, other wearers need an intensive amount of encouragement and coaching just to get the devices correctly placed in their ears --- and don’t even mention the amount of time it takes some wearers to successfully pair their hearing aids with Bluetooth streaming to their smartphone! Maybe the one certainty about follow-up care is that it is uncertain. Both the time it takes to solve the problem or “get it right” as well as the type of follow-up care appointment vary in unpredictable ways. For these reasons, follow-up care, both when it is delivered, and how it is delivered are the focus of this 2-part article.

Everyone Does It, But No One Talks About It

Although there is surprisingly little evidence supporting its effectiveness, follow-up care has been a standard part of hearing aid provision for decades. Both the American Academy of Audiology (AAA) and the American Speech and Hearing Association (ASHA) have created best practice protocols for adult hearing aid wearers. Neither organization specifically prescribes a certain number of visits, frequency of visits, or type of appointment that construes follow-up care. However, both organizations state in their best practice protocols that additional visits beyond the hearing aid fitting session may be required.

More recently, the Audiology Practice Standards Organization (APSO) created S2.1 Hearing Aid Fitting for Adult & Geriatric Wearers. Issued in May 2021, it is a 15-point standard that outlines what APSO’s expert panel believes leads to quality wearer outcomes for adults and geriatrics fitted with hearing aids. In this APSO standard, the following four points are components of routine care that usually begin on the day of the fitting and often necessitate additional follow-up visits with the hearing care provider.

- Orientation of device- and wearer-centered and includes use, care, and maintenance of the hearing aid(s) and accessories.

- Counseling is conducted to ensure appropriate adjustment to amplification and to address other concerns regarding communication. Additional rehabilitative audiology is recommended if deemed appropriate.

- Hearing aid outcome measures are conducted. These may include validated self-assessment or communication inventories and aided speech recognition assessment.

- Short- and long-term follow-up is conducted to ensure that post-fitting needs are addressed. This includes updated audiological assessment, hearing aid adjustments and routine maintenance as needed to ensure the devices are functioning properly and appropriately for the wearer.

https://www.audiologystandards.org/

By design, APSO standards inform hearing care providers (HCP) on what to do during follow-up, but they are silent on how to deliver the various facets of follow-up care. It’s really up to each HCP to take the APSO standards and decide how they want to implement them in the clinic. Since a core component of prescription hearing aids provision is that follow-up care is bundled along with the sale of the devices, it has been easy to offer all wearers the same undefined follow-up care appointment time. For decades, “come back in 2 weeks” or “return in a month and we will see how things are going” has been the norm. What happens during those periodic, scheduled follow-up visits, and how many of them are needed to optimize wearer outcomes, is shrouded in mystery. Every HCP offers their own version of follow-up care, but because little has been published about it, we don’t really understand what components of follow-up care might be the most valuable to the wearer or which ones could be augmented or perhaps even replaced with artificial intelligence. Which parts of it could be delivered remotely or delegated to the wearer using smartphone apps? Should follow-up care focus more on the device or the person? What role might new generation AI-driven hearing aid features play in the follow-up process? All questions this two-part article attempts to address.

The Long Tail of Follow-up Care

Known by some as aftercare, HCPs recognize the importance of periodic follow-up visits and how these visits lead to successful wearer outcomes. In a traditional bundled model of care, one still widely used today, wearers fitted with hearing aids are typically provided an unlimited amount of service over a specified timeframe. More specifically, following the initial hearing aid fitting appointment, most practices schedule one or two additional follow-up appointments over a 30-to-90-day period. In the traditional bundled model, after those first few scheduled follow-up appointments, wearers are seen as needed at no added cost. Just how many follow-up appointments are conducted with the typical wearer and the number of follow-up visits needed to optimize wearer benefit are important questions.

To address these questions, let’s turn to a couple of studies. First, we examine the number of follow-up appointments over the first year of hearing aid use. Ramachandran, Stach, and Schuette (2012) calculated the total number of follow-up appointments over a 1-year period following the initial acquisition of hearing aids. As part of their study, they examined various wearer, device, and cost factors to determine the relationship with the number of visits.

They reported that the total number of post-fitting follow-up appointments was 1,567 for an average of 3.12 encounters per wearer in the year following the hearing aid acquisition, including walk-in visits seen by a hearing aid technician. In most cases, wearers were scheduled with an audiologist for an appointment of at least 30 minutes duration. Interestingly, the authors reported that walk-in types of services accounted for 35% of the follow-up appointments with the other 65% of follow up time consisting of scheduled appointments.

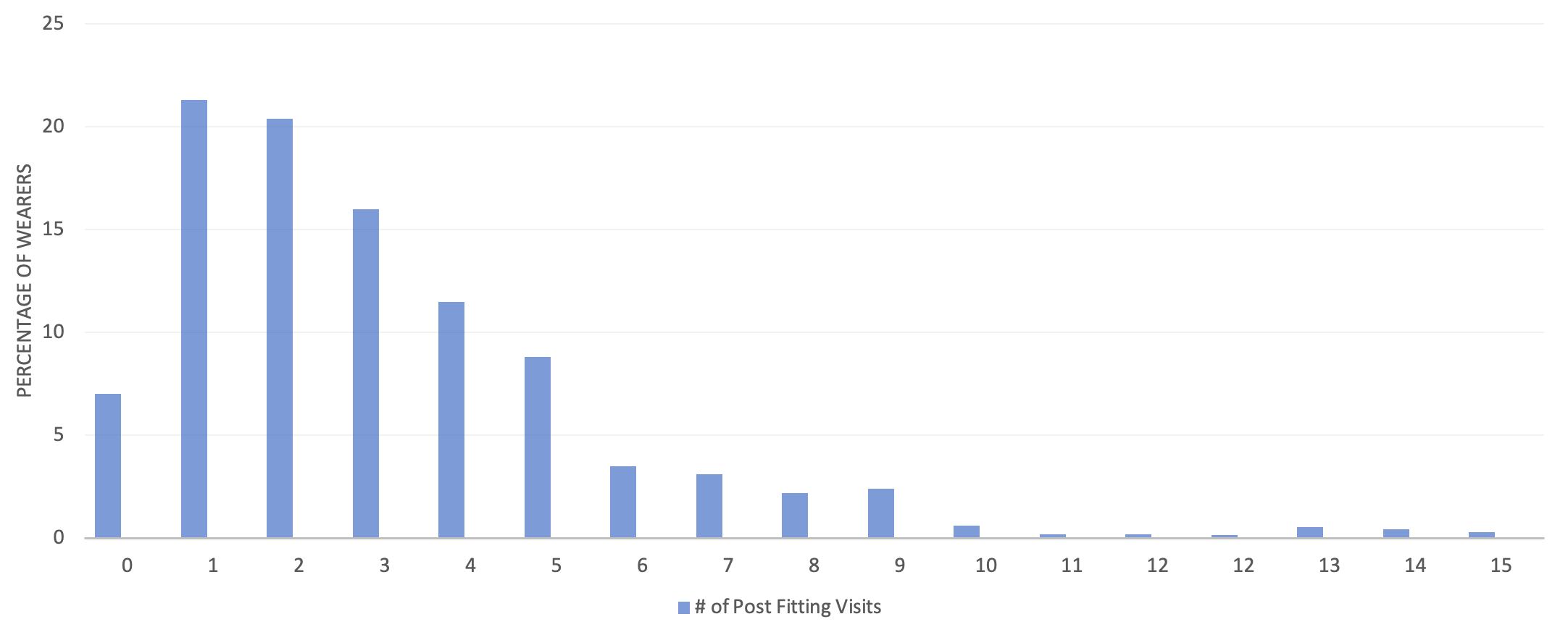

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the number of follow-up appointments, expressed as a percentage of total wearers. Although the average number of follow-up appointments is just over three, Figure 1 demonstrates most wearers were clustered in the range of 0 to 5 encounters, while a considerable number of wearers returned for six, to as many as 15, visits in the year following hearing aid acquisition. The results shown in Figure 1 indicate about one-third of wearers fitted with hearing aids during the 1-year tracking period needed four or more follow-up visits. Further analysis of the data by the authors indicated that wearer factors, including gender, age, and degree of hearing loss, did not impact number of follow-up appointments. However, level of hearing aid technology and associated wearer device cost appeared to play a significant role in the number of follow-up visits. Wearers who acquired higher levels of technology and paid out of pocket for their devices, tended to increase the number of follow-up visits. In contrast, insurance reimbursement, which lowered cost to the wearer, tended to reduce the number of follow-up visits.

Figure 1. The long tail of follow-up care. Percentage of all wearers by number of post-fitting follow-up appointments. Data from Ramachandran, Stach, and Schuette (2012).

As the authors note, the relationship between wearer benefit and the number of follow-up visits appears to be complex, as a higher number of visits does not equate to better wearer outcomes. They cite, for example, Kochkin et al’s (2010) analysis which suggested that more than three visits in the hearing aid acquisition process was strongly related to “below average” real-world outcomes. Additionally, it is worth noting that data in this study was collected before direct streaming to smartphones via Bluetooth was available. There are several anecdotal reports suggesting Bluetooth pairing issues might have an effect on these numbers, possibly increasing the average follow-up appointment time since this study was published in 2012.

Given that most wearers require more than one follow-up appointment, it is helpful to better understand the most common types of service and support needed by wearers during these appointments. Next, we examine the types of service and support considered to be part of the traditional follow-up care process. The most common types of service and support, delivered during follow-up care visits can be divided into these five categories:

- Fine-tuning (shaping gain, frequency response, etc. using the hearing aid manufacturer’s fitting software to adjust, tweak or re-program the devices)

- Fit-related adjustments (assessment and remedying of the physical fit of the device in or around the ear)

- Coaching/counseling (a broad category that can be divided further into personal adjustment counseling, auditory training/aural rehabilitation and informational counseling that provides additional guidance and support related to hearing aid use and orientation to the devices.)

- Feature activation (using the manufacturer’s fitting software to activate a feature, provide a firmware update to the devices, conduct Bluetooth pairing.)

- Service/repair/trouble with hearing aid (a problem with the device that warrants troubleshooting by the audiologist or an assistant.)

Each follow-up visit can be placed into one of these categories. Further, each follow-up visit with an individual wearer might involve one or more of these categories. Tecca (2018) followed 144 hearing aid wearers (mean age = 71.4 years), split into two main groups: Inexperienced RIC wearers and experienced wearers of any style device. After the initial hearing aid fitting, each group was tracked over the course of a year and the types of service and support each wearer needed was recorded. All wearers were required to return for one routine follow-up appointment at approximately two weeks after the initial fit. After the first required follow-up appointment, the audiologist and wearer determined if additional follow-up visits were needed. Table 1 shows the percentage of wearers who returned for follow-up care after their first required scheduled aftercare appointment.

| Inexperienced RIC Wearers | Experienced Wearers |

Follow-up visit 2 | 50% | 54% |

Follow-up visit 3 | 38% | 27% |

Follow-up visit 4 | 12% | 20% |

Table 1. The percentage of wearers needing some type of service or change during follow-up visits 2, 3, and 4. From Tecca (2018).

Generally, the percentage of individuals in need of additional follow-up visits were similar between the two groups. Note in Table 1 that for each subsequent follow-up visit, the percentage of wearers who returned for it declined.

Tecca (2018) also tracked the types of services needed by wearers during each follow-up visit. With few exceptions, follow-up visits involving fine-tuning were the most common type of service provided across follow-up visits 1-4 for both groups. Table 2 shows the percentage of wearers who returned for a follow-up appointment that involved fine-tuning of their devices. For example, of the 27% of experienced wearers (shown in Table 1 above) who returned for follow-up visit #2, 26% of that group (shown in Table 2 below) needed fine-tuning of their devices.

| Inexperienced RIC Wearers | Experienced Wearers |

Follow-up visit 1 | 28% | 58% |

Follow-up visit 2 | 38% | 26% |

Follow-up visit 3 | 26% | 24% |

Follow-up visit 4 | 20% | <10%

|

Table 2. The percentage of wearers in need of or requesting fine-tuning of their devices during follow-up visits 1-4. From Tecca (2018).

Curiously, on follow-up visit #1, a much higher percentage of experienced wearers needed fine-tuning of their devices, as 58% of this group needed some sort of adjustment or fine-tuning of their devices. This higher percentage among experienced wearers might reflect how wearers with previous hearing aid experience are more opinionated, savvy, or direct about the sound quality of their devices compared to new wearers, who may be unfamiliar with what to expect during their initial experience with hearing aids. Also note in Table 2 that with each successive visit, the percentage of wearers who needed fine-tuning declined, while the need for other services from the hearing care provider tended to increase. For example, Tecca (2018) data indicated 30% of inexperienced RIC wearers needed a fourth follow-up visit for coaching/counseling and/or service.

In a similar study, Solheim et al. (2018) tracked the hearing aid experiences of 181 wearers during their first six months of use. The participants were a group of older wearers (average age 79 years) fitted with new hearing aids. The group included first-time (46%) and experienced (54%) hearing aid wearers. Most hearing aids were behind-the-ear (86%) devices. Wearers, who were able to return to the clinic as needed for periodic follow-up visits, were interviewed at the end of their first 6 months of use. At the 6-month interview, it was found that just under 85% of participants were using their hearing aids, and 16% had discontinued use. Use was defined as participants wearing their hearing aids more than 30 minutes per day and non-use as less than 30 minutes per day as calculated by the device’s data logging system. The average daily wear time of the 85% participants who were determined to be “hearing aid users” was 7.2 hours.

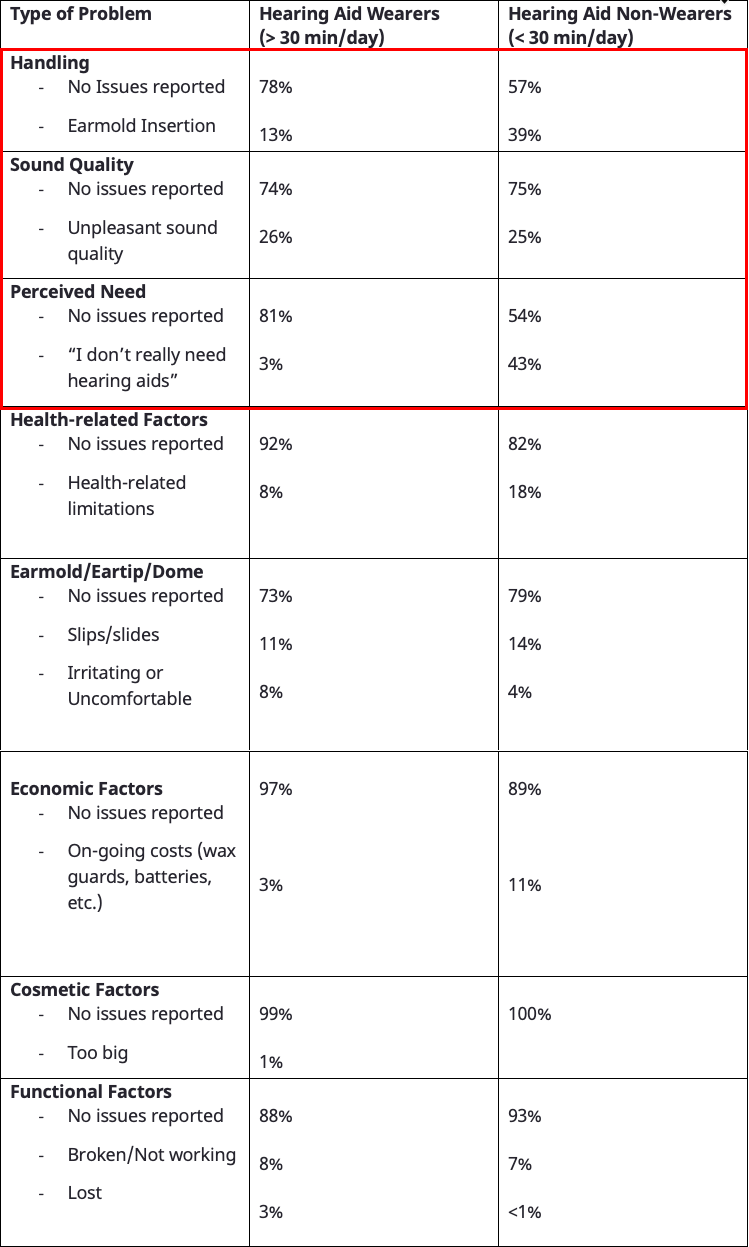

Table 3 compares the types and rates of occurrence of problems for two groups: hearing aid wearers (wore >30 minutes per day) and non-wearers (wore < 30 minutes per day). Each type of problem was defined by the authors as follows: Handling involved any issues related to inserting and removing the hearing aids as well as changing the batteries or wax guards. Sound quality encompassed any issue that warranted an adjustment to the signal processing of the hearing aid. Perceived need reflected wearers’ self-reported perception that they needed or would benefit from hearing aids. Health-related factors were comprised of any physical limitations or difficulties that would limit or preclude the use of hearing aids. Earmold factors involved any issue related to the physical fit of the devices in the ear. Cosmetic factors related to wearers’ perception of the appearance of the device as worn on the ear. Economic factors related to the cost of wearing devices. Finally, functional factors related to the general functioning of the devices, such as a broken hearing aid.

Table 3. Reported issues associated with hearing aid use for two groups, wearers vs. non-wearers Percentages rounded to the nearest whole number. From Solheim, et al (2018).

In addition to the type of problems, the authors also tracked the number of problems reported over the course of the wearers first six months of use for all 181 participants. Table 4 breaks down some of the key characteristics as they relate to the number of reported problems. Only hearing aid use, calculated as the number of hours per day, was significantly associated with the number of reported problems. Age, degree of hearing loss, gender, and prior hearing aid experience were not significantly associated with the number of reported problems.

Number of reported problems | % of wearers | Average Age | Hearing aid use (hours/day) |

None | 27% | 79.8 | 8.4 |

1 | 28% | 80.0 | 5.9 |

2 | 27% | 77.6 | 4.9 |

3 | 13% | 81.0 | 4.9 |

4 | 4% | 75.0 | 4.1 |

5 | 1% | 73.0 | 3.5 |

Table 4. Relationship between number of hearing aid problems reported and age and hearing aid use for all 181 participants. From Solheim, et al (2018).

The results of this study, summarized in Tables 3 and 4, shed light on some important aspects of follow-up care. One, 73% of all wearers reported one or more problems within the first six months of hearing aid use. This finding underscores the need for periodic and consistent follow-up care in order to minimize or eliminate these problems. Myriad problems can arise at any time and the act of acquiring hearing aids is seldom a “one-time purchase.” Rather, it should serve as a reminder that the hearing aid acquisition process is one requiring occasional on-going care from the HCP. Given that a substantial reduction in wear time is observed for those participants reporting even just one problem, as shown in Table 4, hearing care providers play an essential role in identifying and remedying these problems throughout the lifespan of the hearing aids.

Two, the top-three most common problems that lead to hearing aid non-use are outlined in the red box in Table 3: Handling, sound quality and perceived need. According to this study, 25% of non-wearers report problems with sound quality, 39% of non-wearers report problems with handling and 43% of that group report issues with perceived need. It is reasonable to assume that if those top-three problems were resolved quickly, it would lead to higher rates of use.

Three, both the Tecca (2018) and Solheim et al (2018) studies indicate the pervasive need for additional fine-tuning during follow-up visits. Tecca’s data showed that upwards of one-third of both experienced and inexperienced wearers returned to the clinic for two or more follow-up appointments involving fine-tuning. Similarly, Solheim and colleagues found an equal number of hearing aid wearers and non-wearers (about 25% of each group) reported issues related to sound quality that required some type of fine-tuning on the part of the provider during the first six months of use. Given that an equal number of hearing aid wearers and non-wearers (~25%) reported “unpleasant sound quality,” suggests this problem is common among all wearers, a problem that doesn’t necessarily lead to non-use. And in many cases, a problem addressed effectively with timely fine-tuning.

The Catch-22 of Follow Up Care

Together, these three studies demonstrate the unpredictable nature of follow-up care and the vital need for the hearing care provider throughout the rehabilitation process. It simply takes time for most hearing aid wearers to become acclimated to new sounds, to learn how to properly use their devices, and to effectively manage all aspects of their experience with hearing aids. That it takes some wearers substantially more time than others is not surprising. Results of these studies, however, indicate that about one-third of wearers need four or more follow-up visits to have a chance at being successful hearing aid wearers. Given all the factors associated with successful hearing aid use, a relatively large number of wearers need multiple, often unplanned, follow-up visits, which, from their perspective, can be time-consuming, inconvenient, and could lead to indifference, frustration, and eventually non-use.

From the perspective of the hearing care provider, the time it takes to methodically identify and successfully address each problem can be burdensome too. Each follow-up appointment scheduled with the hearing care provider typically involves 30 minutes of clinical time. And data from Ramachandran et al. (2012) suggests about one-third of follow-up appointments involve unscheduled walk-ins, which create additional challenges for HCPs and their support staff.

Even when the encounter with the wearer takes just a few minutes, it is often the case that one-half-hour of time is blocked on the schedule. This is 30 minutes of time that could be used for other revenue-generating opportunities, such as fitting hearing aids on new patients. As Figure 1 illustrates, about 18% of wearers requested/needed five follow-up appointments. That equates to 2.5 hours of follow-up time for nearly 1 in 5 patients. Nearly twice as much time is devoted to follow-up care compared to a wearer returning for two or three follow-up visits. The unpredictable nature of follow-up care - that some wearers need several hours, while others need very little -- is a Catch-22: To ensure that current wearers receive the care and attention they need to be consistent hearing aid wearers takes away valuable clinical time from other prospective wearers who also need care and attention. Every person with hearing loss deserves the time and attention of the HCP for however long it might take to achieve reasonable outcomes, but in any healthcare profession, there are a finite number of hours over the course of a month or week that can be committed to direct patient interactions. Consequently, HCPs should be encouraged to embrace innovations that augment follow-up care or enable a greater level of convenience for patients to receive ample follow-up care without compromising outcomes.

Although quality “face time” with all wearers must remain a priority when the number of follow-up appointments over the course of one year for a single patient exceeds three, outcomes can be negatively impacted (Kochkin et al. 2010). Hearing care providers should be thinking about alternative approaches to patient care that optimizes the number of follow-up visits, and frees up time to see other persons with hearing loss – yet maximizes outcomes for the individual. The judicious use of AI-based fine-tuning apps and a renewed emphasis on person-centered counseling that moves people into the action stage of change and promotes consistent hearing aid use has the potential to improve wear time – topics we cover in Part 2 of this article.

References

Kochkin, S., Beck, D., Christensen, L., et al. (2010). MarkeTrak VIII: The impact of the hearing healthcare professional on hearing aid user success. Hearing Review, 17(4), 12-34.

Ramachandran, V., Stach, B., & Schuette, A. (2012). Factors influencing wearer utilization of audiologic treatment following hearing aid purchase. Hearing Review, 19(2), 18-29.

Solheim, J., Gay, C., & Hickson, L. (2018). Older adults’ experiences and issues with hearing aids in the first six months after hearing aid fitting. International Journal of Audiology, 57(1), 31-39.

Tecca, J. (2018). Are post-fitting follow-up visits not hearing aid best practices? Hearing Review, 25(4), 12-22.

Citation

Taylor, B. & Jensen, N. S. (2023). How AI-driven hearing aid features and fresh approaches to counseling can promote better outcomes: part 1, the catch-22 of follow-up care. AudiologyOnline, Article 28670. www.audiologyonline.com