Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials.

Craig Castelli: Today we are going to cover topics related to buying and selling a private practice. The content should apply equally whether you are planning to buy a practice or planning to sell.

Overview

We will talk about transaction structures and different ways a deal can come together. Related to that are some of the key points of negotiation in almost all transactions. Ron will talk you through strategies for valuing a practice, and then we will conclude with case studies. I will warn you that the initial part of the conversation today will be a bit technical. There are certain things that come into play in almost every single transaction, and most people are not aware of them until they are going through the deal. If you have some knowledge ahead of time, it can help you when you enter into a transaction.

Transaction Structures

Let’s talk about how transactions are structured from a legal standpoint. When you buy or sell a company, there are only two ways that you can structure the deal. You can sell the assets in your business, in which case the buyer transfers those assets into a new corporation. Those assets include the equipment, furniture, files, and the right to use the business name and any good will as a part of it. In this case, the buy is not actually buying a company. The company still exists, and eventually the seller will dissolve that entity. The alternative is to sell the stock in your company, in which case the buyer is buying the company itself, and the assets go along with that. I will go over the pros and cons of these two deal structures.

One thing I would like to make clear is that the vast majority of transactions, both in the audiology industry and among smaller businesses in general, are structured as asset sales. In my career doing mergers and acquisitions, I rarely saw a stock sale, unless it was a company that did $100 million or greater in revenue. In the last four years, we only had one deal in our firm that was structured as a stock sale; the rest were structured as asset sales. I like to prepare anyone who is preparing for an eventual sale of a practice to plan for an asset sale. With that said, let’s talk about the differences between these two deal structures.

Asset versus Stock Sale

Asset sale. There are significant advantages for a buyer to structure a deal as an asset sale. The first is limitation of liability. When purchasing assets, the buyer is not inheriting any of the financial or legal liabilities that may exist to the business.

Financial liabilities could be unpaid bills or long-term debt that remains with the seller of the business and legal liability may result from a lawsuit to fraud to tax audits; that liability also remains with the seller. There is a clean break at the closing. The buyer is responsible for everything that happens from the closing date forward and the seller maintains responsibility for everything that happens prior to the closing date.

There is also an accounting advantage which enables the buyer to select their own accounting methods. If they want to switch from cash to accrual or make other changes to accounting methods, it is very easy to do so. It also allows them to depreciate and amortize the full purchase price. In the years immediately following the sale, there are some measurable and significant benefits to having purchased the assets because you can depreciate and amortize, and therefore reduce your taxable income.

The cons of an asset sale vary based on the structure of the business. For Limited Liability Corporations (LLC), S Corporations (S-Corp), sole proprietorships or partnerships, which are the business entity structures that apply to the vast majority of small businesses, the cons are limited from a tax standpoint. You will get tax and capital gains for the vast majority of the purchase price. If you are a C Corporation (C-Corp), there is a serious issue at play here, and that is double taxation. Companies structured as C-Corp, which only applies to larger companies with several shareholders, are taxed at the corporate level and again at the individual level. When the owner of a C-Corp sells the assets, the taxes they have pay are exponentially larger than any other entity type.

If you are a small business owner structured as a C-Corp and you are planning to sell in the next five to ten years, I would encourage you to talk with your CPA about changing your entity to an S-Corp or an LLC. You cannot make the switch at the last minute, mostly because the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) will most likely catch on to what you were trying to do in order to avoid taxes, and you are highly subject to an audit. It is beneficial to establish at least a brief history. Most certified public accountants (CPA) would tell you 10 years, but you need at least a few years as another entity type before you sell the practice in order to capitalize on those tax advantages. Even if you are an S-Corp or LLC, there is a portion of the purchase price that is taxed as ordinary income instead of capital gains, but in audiology, because these businesses are so asset light, it is somewhat insignificant. It is a very small increase in the total taxes that are paid.

The other con is that there is difficulty in transferring contracts, licenses, and leases. When you purchase the assets of a business, you cannot legally purchase any contracts, any employees, any leases, or any business licenses. You have to go in and establish or assign all of the contracts. You have to enter into new employee agreements with employees. You have to resign the lease. It is a lot of extra work. In my experience, there is never really an issue in doing this. You are able to operate the business the same way it was before you took over, but there is extra preparation for the transition.

Stock sale. The pros and cons of a stock sale are the opposite of those of an asset sale. When you purchase the stock of a company, you are automatically inheriting all the contracts and all the licenses. Also, 100% of the purchase price allocated to stock is taxed as capital gains. Theoretically you allocate some of the purchase price to something else, but generally when you sell the stock, 100% of the proceeds are taxed as capital gains and there is a slight tax advantage there. The cons are for a buyer, as all financial and legal liabilities are assumed. There is no change in the asset basis. Old depreciation schedules are maintained, and they cannot amortize the price allocated stocks. They do not have any of the tax benefits associated with selling the assets.

Those of you who are on the seller side may be thinking, “What if you insist that this is a stock sale. There is a negotiation, right?” You certainly can. If you are dealing with a buyer who is not advised by an attorney or accountant and is inexperienced at buying a business, you may get away with it. The vast majority of buyers will simply refuse to purchase businesses in any other fashion than an asset purchase. When I made the comment earlier to expect the sale of your business to be structured as an asset sale, this is why. It may be the only way to get the deal done.

Price and Payment Terms

Let’s talk a little more specifically about the terms that you are going to negotiate. Certainly, price is a key element of the negotiation. You are going to establish an asking price. The buyer is going to value the business on their own, and you will hopefully align on a number that makes sense for the both of you.

Once you determine a purchase price, the next item to negotiate is how that purchase price is paid. The four most common ways to structure the payment of a purchase price are cash, deferred payment, earnout and seller note.

All Cash

All-cash means the buyer writes you a check for 100% of the purchase price at closing. This is the best scenario for a seller, but it is also extremely rare for all-cash deals to take place today. Typically, when they do, they are at lower valuations. Anytime you hear stories about lofty purchase prices and premium valuations, there is usually some element of a payment structure attached to it. The three types of payment structures that can be attached are deferred payment, an earnout, or a seller note.

Deferred Payment

A deferred payment is exactly as it sounds; a portion of the purchase price is held back and is paid in a lump sum at a later date. The timing of the payment varies and depends on the deal structure. This is usually a guaranteed payment. It is not contingent on any sort of performance of the business. Sometimes there is a contingency regarding a transition period, owner employment period, or owner employment agreement after closing. The performance of the business is not relevant to this payment. It is a relatively secure structure for a seller.

Earnout

The next option is an earnout. This injects a little more variability into the deal, because part of the purchase price has to be earned based on the performance of the business. Whether that means maintaining historical averages or active growth, the seller has a part of that price at risk. If they miss the targets, then the payment could be reduced or dissolved altogether. The flip side of that is it also injects upside into the equation, whereby if you exceed the agreed-upon targets, the payment can actually increase.

I am not a big proponent of earnouts. However, I will say businesses that are growing at a very high rate, perhaps double or triple the industry average with 8% to 10% a year, can benefit from earnouts if they are able to sustain that growth in the years following the sale. There is a way to increase a purchase price or in some cases, close a valuation gap.

Seller Note

The final option is a seller note. This is where the seller acts as a secondary secured lender to the buyer and the buyer is makes payments on a regular basis to the seller over a period of several years, until a portion of the purchase price is paid down. This is becoming more common in deals where individuals are purchasing practices. It is usually a small part of the purchase price, but there is a little bit of risk here. The ability to make those payments is tied to the new owner’s ability to make the payments. If the business does not do well, then they are going to have an issue making the payments, and you might not receive 100% of the seller note.

Tax Treatment and Asset Allocation

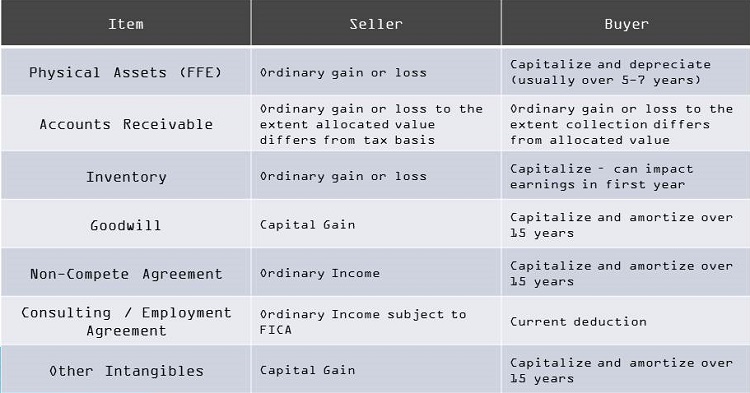

Let’s talk about tax treatment and the asset allocation. In an asset sale, part of the purchase price is taxed as ordinary income, and part is taxed at capital gains. When you sell the assets in your business, you break the purchase price up into several chunks. You allocate chunks to different assets. For example, I am paying you X for the furniture and the equipment. I am paying you Y for the files and the goodwill. I am paying Z for the non-compete. Figure 1 is a table that lists a number of different assets to which a purchase price could be allocated. The reality is that there are only three that come into play in the vast majority of transactions. These are physical assets, goodwill and a non-compete.

Figure 1. Potential assets and purchase allocation.

Physical Assets

Part of the purchase price is allocated to physical assets, and the seller is taxed as an ordinary gain or loss. This means your ordinary income taxes apply to this part of the sale price. The buyer, on the other hand, can capitalize and depreciate this amount over five to seven years.

Goodwill

On the other hand, goodwill is taxed to the seller as a capital gain, but the buyer can only amortize goodwill over 15 years. There is a point of potential opposition here between a buyer and a seller. It is better for the buyer to have as much of the purchase price as possible allocated to physical assets. It is better for the seller to have as much of the purchase price as possible allocated to goodwill.

The reality is that audiology practices are asset light. We are not talking about several hundred thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment per physical location. In most transactions, there is only a small amount of the purchase price that is allocated to physical assets, maybe 5%, 10% or 15%, depending on the size of the deal. This is usually the threshold for a physical asset allocation, with the vast majority of the rest of purchase price allocated to goodwill. I made the comment earlier that the seller of a business does not typically realize a huge difference between a stock sale or asset sale from a tax standpoint, and this is why. It is a marginal amount of the purchase price that is taxed as an ordinary gain or loss, and it does not increase the tax obligation over a stock sale by a considerable amount.

Balance Sheet

One of the final items to negotiate is the balance sheet and how assets and liabilities are handled. The assets on your balance sheet are cash, accounts receivable, inventory and equipment. The liabilities are accounts payable, salaries and taxes payable, potential credit returns of hearing aids, and any long-term debt.

In most common structures, there is an accounting cutoff at closing whereby the seller retains all of the assets and the seller keeps all the cash. The seller has the right to collect all the receivables. Likewise, the seller retains all the liabilities. The seller has to pay off all the payables. They have to pay down any long-term debt. It is a very simple and clean way to manage a transaction, and it is the most common. It would be very rare for a buyer to take on accounts receivable or to take on any payables.

The one liability that is standard for a buyer to take on would be warrantees, free service repairs, and things of that nature. A seller is typically liable for any credit returns. Typically the money follows the hearing aid sales, so if the seller collected the payment for the hearing aid and the patient returns it, the seller has to issue the refund. However, if someone purchases a hearing aid and there is a warranty attached to it with free service or free batteries, then it is standard for the buyer to take on those liabilities and continue servicing the patients the same way they were serviced prior to the transaction.

Transaction Documents

When you enter a transaction, there are three primary legal documents that you will negotiate: the letter of intent, an asset purchase agreement and a non-compete.

Letter of Intent

The letter of intent is the formal offer issued in writing by a buyer proposing the terms of the transaction. It will contain your purchase price, payment terms, any transition or employment terms, and the basic terms of the non-compete. Both parties will sign this document and the seller has effectively accepted the offer. They have not sold the business yet, but they have accepted the offer, enabling the buyer and seller to move into a more advanced stage of due diligence and negotiate towards a closing.

Asset Purchase Agreement

The primary contract of a transaction is called an asset purchase agreement. This is the purchase contract entered into between the buyer and the seller. This will contain the same information as the letter of intent, only in much greater detail. It will also spell out restrictive covenants, such as non-compete, with much stronger legal language attached, as well as any nondisclosure, non-solicitation or other covenants that are part of the deal.

Representations and warranties is a section through which the seller is guaranteeing or representing certain facts about the business. Some of these, for example, might state:

- I am not aware of any tax liabilities.

- I have not committed fraud.

- I am the sole owner of this business.

These things legally enable the owner to sell the business.

The asset purchase agreement also contains any pre-closing conditions the buyer may wish to impose.

Non-Compete

The final document is the non-compete. It is a restrictive covenant barring the seller from competing with the new owner. The two key elements of this are the term, which spells out the number of months or years it is in effect (three to five years is the most common), and the geographic scope, which is defined as a radius around the office or offices, usually between 25 to 50 miles around each location, depending on where you are in the country.

The Deal Team

Entering into a transaction is a lot of work and foreign territory for most audiologists. There are several professionals who can help you through the process. You absolutely need to work with an accountant and an attorney. The attorney is the most critical person you could hire because it is a legal transaction and should be handled appropriately. You could also consider hiring a business broker, preferably someone who has experience managing transactions. They can help you negotiate somewhat, as well as help manage your attorney, your accountant, and all the other stakeholders in the transaction.

Valuing your Business

Dr. Ron Gleitman: Let’s continue with the same discussion points, but with a little different perspective. I recommend anyone who is thinking about selling their business to read What Every Business Owner Should Know about Valuing Their Business (Feldman, Sullivan, & Winsby, 2002). One of the main topics in the book is managing your business life events. An example of a business life event is preparing your business for sale. Other business life events are managing your assets and protecting your assets with the proper insurance.

One example in the book tells of someone who owns an insurance company wanting to sell their business for $5 million. A buyer offers $4 million, and the seller rejected that offer. Unfortunately, the seller then got ill within nine months and could not work. The business revenue dwindled and they had to sell the business two years later for $2 million. It is all about timing and what is the best opportunity for both the buyer and seller.

The other thing I like to talk about is transitioning your business from a C-Corp to an S-Corp or LLC. Many small business owners in the United States are minimizing their taxes and not maximizing the value of their business. Maximizing the value of your business takes preparation. You cannot do it overnight and expect to sell your business nine months later when the business is not in the financial condition that you need. It takes time, just like preparing for the right taxation.

Business Valuation

The business valuation is based on an evaluation of all the components of your business. The value is the analytical process of determining the price a willing buyer is willing to pay and a seller is willing to accept without ever putting up the business for sale. This is an IRS definition of fair market value. If I am an owner and think I want my business to be worth $1 million, can a willing buyer put up $1 million in exchange for it? If so, that is determined as fair market value.

Expectations are different on both sides, and usually in a good deal, everyone has to compromise on some things. My advice to a seller is to think about your bottom line. When I wanted to sell my business for $1 million, I needed to know my lowest threshold. After the asset purchase agreement, the asset allocation, and non-compete, if $900,000 is your low point, you should take that offer if someone gives it, because you have met your conditions.

Valuation

The Date

The value of your business is a function of the economic times. It is also important to put the proper value on a business by how accurate and transparent the available information is. All the things you are telling a potential buyer about your business can be documented clearly as fact. Having clearly defined profit/loss (P&L) statements and tax returns to validate those P&L statements is important.

What is most important is the recent data. Most people will look at a minimum of the last three years, and then what happened the last quarter if you are in the middle of a calendar year.

What is Being Evaluated

What do you evaluate for the valuation? This is the ongoing operation of the business plus any non-operating sources of income. If you own the building and are paying yourself rent, that has to be evaluated. Is the building part of the transaction that is being sold as an asset as well? Valuation is important for transparency, clarity of data, and the conditions of the industry and the economy.

Transparency

The greater the transparency, the easier it is to put a higher value on the business. It also minimizes the risk of the buyer. This means everything that a business appears to be is truly what it is. Traditionally, this is very easy in publically traded companies. However, in our industry, we are privately held companies. To prepare your business for sale three to five years ahead of time, make sure there is high transparency in the business so you command a higher value and minimize the risk of the purchaser.

One of the things I find interesting in consulting with buyers and sellers is that everyone thinks their P&L statement is sacred information. From my perspective, it does not tell anyone how you got to those results, what your sales strategy is, what your marketing strategy is, or what your people management strategy is. That is the core of a good business. The results indicate how much revenue you produce in managing your expenses, resulting in a profit. P&L statements have to be very clear, but it is just a point-of-time reference for information about the business and how it is functioning. It does not divulge how you got there.

Useful Pieces of Information

Many clients ask if the market is staying the same or changing. My overall answer is the industry is changing. The financial condition of our country has been poor the last few years, although it is starting to slowly make progress. There have been significant changes in the financial markets of the country.

The second question is whether there have been changes in the industry in which we all operate. Again, I would say yes. Vertical integration has been a common theme on the manufacturer side, which means that manufacturers are buying up some of their distribution. In vertical integration, they have control of the whole process from manufacturing to the retail. That is continuing to increase.

The third industry change is a shift in private pay to third-party payers. That increase in third- party payers is changing the bottom line dramatically. When we talk about valuing a business and look at cash flow, it is important to understand third-party payers and the trends in that business, but the bottom line will be the overall profit of the business.

Have there been any other changes in the business as a whole? I say yes. For the first time, I see practices struggling. Ten and 20 years ago, practices were able to succeed more easily. Today there is a more competitive market. We have the Internet, big-box as retailers, manufacturer-owned businesses and third-party payers. These are all the things that are contributing to a different landscape of our industry and have to be taken into account wisely in the transaction of purchasing a business. I still believe there is a significant amount of opportunity in private practice, but you have to make wise business decisions.

Assessment Components

To value a business, you have to look at all the components of the business. The three major components are assets (fixed equipment), goodwill and everything else after that.

What are the assets? We have professional equipment and office equipment. The other assets or things that need to be analyzed are the market in which you are going to buy or sell. You look at the competitive analysis of that business by who the competitors are and how they compete. There are always four competitors in the marketplace: retail, big box, the medical environment, and private practice (either audiologists or dispensers).

What has the marketing strategy been of the practice that you are potentially buying? What has the budget been? Can you get a return on investment for the marketing spent for those activities? A review of the sales staff, hearing professionals, office staff and others contributing to the practice is needed.

Next, you have to look at the contracts. Are there contracts whereby services are provided in ENT offices? Are you on third-party payers and insurance companies? What is the revenue breakdown by the contract?

Understand the cost of running your business per hour. I cannot stress this enough. When you agree to take on a contact, does that contract provide enough revenue to cover your break-even point? If you assign a diagnostic hearing test for a half hour and it costs you $150 an hour to run your business based on your fixed expenses (operating expenses, plus fixed labor, divided by the number of hours you are open), do you meet break even? Are there any other intangibles that can be provided, such as access to more potential hearing aid patients?

You have to look at the work flow of the practice. What does the appointment book look like? What is the staff productivity? Are there gaps? How can you as a business buyer take advantage of those opportunities? We also have to look at the P&L statement, the cash flow of the business, the balance sheet and liabilities and assets of the business.

Analysis

We will look at the time frame of selling or acquiring a business. As I said, most people want to look at a minimum of three years as well as the current year-to-date. You want to calculate the profit of the hearing aid sales, the profit of the professional fees (diagnostic fees and fees for services), revenue by payer (insurance and third-party payers), revenue by referrals sources and the impact on referrals coming into the business when you are looking at purchasing it. Are those referral sources going to transfer easily to new ownership? It is important to understand the impact that it can potentially have on losing a referral contract when it is an asset purchase. Even with the small likelihood of a stock purchase, some of those contracts should transfer, but that does not mean that people will automatically continue to refer to the new entity.

Evaluation

There are four traditional evaluation methods to value the business. One is the asset-based approach. One is a value to the earnings or profit of the business. Another is a multiplier to the overall revenue of the business (traditional net revenues minus all returns and insurance that is not collectible), and last is the discounted cash flow method.

Many people talk about a revenue multiplier. For example, if I have a practice that generates $1 million in revenue, my multiplier hypothetically might be one times revenue, and the business is worth $1 million. For many years, this was the way it was approached. Today, that is not the most prudent way to value a business. It needs to be based on discounted cash flow. It is important for people to understand that the industry is changing from this traditional revenue multiplier to a discounted cash flow analysis. Many people still want to talk about what the multipliers are. However, when the transaction occurs, smart business people, who are both sellers and buyers, will need to look at discounted cash flow.

Craig Castelli: Revenue multiples are no longer the end-all, be-all of valuing practices. One or two corporate buyers will still use revenue as a primary talking point, but I guarantee they are looking at profitability behind the scenes. The corporate buyers as well as any independent practitioner looking to purchase a practice cannot use a revenue multiple. It simply does not make sense for that type of buyer to value business in that fashion.

Discounted cash flow is a net present value calculation. We are taking the projected cash flows of the business in the future over a period of time and discounting that back to today’s value; five years is a typical time period for smaller businesses. What drives this is the profitability of the business. The revenue and total sales do not have much to do with it.

How are you going to finance the purchase if you are buying as an individual? Most likely there will be debt involved. How are you going to pay down the debt? Are you going to use the profits of the business? Figuring out what type of loan payment that the business can sustain and still afford you a reasonable return on your investment is critical to valuing the business, and discounted cash flow is the best way to do it. The calculation is a fairly complex formula, and I could not do it without Microsoft Excel; we will not discuss it today. The point here is for you to start shifting your mindset to look beyond one-time sales or other revenue multiples that might be thrown around the industry to other methods of valuing businesses.

When valuing a business, the first step is to come up with the appropriate calculation of profitability. As anyone who owns a business knows, we do whatever we can to reduce out taxable income. What our tax return says we made does not necessarily reflect how much money we profited from the business. We need to calculate a profit figure that is different from the net operating income or net ordinary income that is shown on our tax return.

There are two figures that you can calculate. One is known as seller’s discretionary cash flow (SDCF) and the other is known as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA).

Seller’s discretionary cash flow. Seller’s discretionary cash flow is a commonly used calculation by sellers of businesses. You take the net operating income of the business shown on the tax return and add back to it depreciation and amortization; these are write-offs, not cash expenses. You add back any one-time or unusual expenses, as well as any expenses not directly related to the operation of the practice. The goal to determine the normal cash flow of the business and how profitable the business should be in the future. To that, you are also adding back the owner’s full salary and wages, and any other fringe benefits the owner is taking. In this way, you can present to a buyer of the business how much total cash flow you have at your disposal. From this cash flow, you can pay your own salary, make loan payments, and also make other investments into the business.

EBITDA. The other calculation is EBITDA, which adjusts for the cost to replace the owner. If I am buying a practice from you and you are retiring, I have to step in and run it myself or if I am not an audiologist, I will likely hire an audiologist to run it for me. There will be a cost associated with that. I am concerned with how profitable the business will be after I have paid that audiologist a reasonable salary.

EBITDA is the most commonly used profit figure across all industries, and that applies equally to the hearing aid industry. It is the only figure that someone buying a practice should use. If you are presented with seller’s discretionary cash flow, it is best to then make your own calculations to determine a reasonable, sustainable EBITDA on a go-forward basis.

Add backs. Let’s talk about some of these add backs from the seller’s point of view. The key element of valuing and calculating add-backs is transparency. When you want to present the profitability of your business and make an argument that it is greater than whatever is displayed on your tax return, you need to be able to support it.

For example, it is very common for owners to write off mileage or lease a car through the business. That is obviously not related to the operation of a clinic, especially if we are talking about one or two audiology practice locations. On the other hand, if we are looking at credit card items that are included in office expense or supplies, it becomes much harder to justify those as add-backs, and the buyer is likely to throw them out and come up with a lower EBITDA figure than you have.

You have two solutions in the final years before selling. The best piece of advice is to eliminate some of these personal expenses in the final years so you have much cleaner P&L and tax return to show a potential buyer. They can never dispute net income.

The other thing is to delineate some of these add-backs. If you are going to run them through the business, at least add an element of transparency. Make it so that anyone who is looking at your P&L can easily identify them and realize that they are not essential to operating the business.

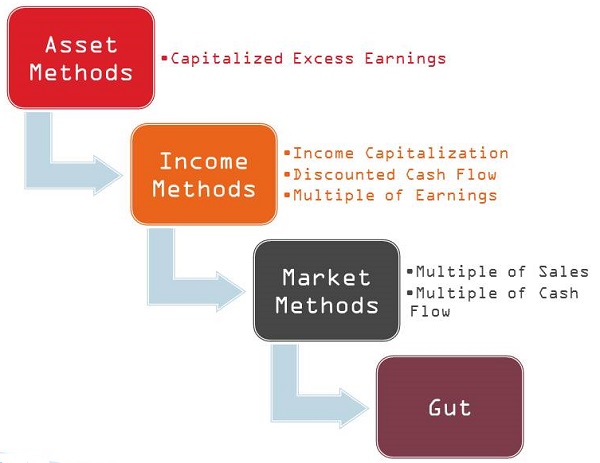

Caber Hill’s Valuation Methods

Figure 2 is a quick view of how we value businesses at Caber Hill. Most people in the financial community agree that discounted cash flow is the best method. However, there is no one right or wrong way to value a business. When we are appraising companies, we will value the assets using method called Capitalized Excess Earnings. We use several methods to value the income capitalization; discounted cash flow is one, as is a weighted multiple of the earnings.

Figure 2. Caber Hill’s valuation methods.

We will also look at the market and see what other companies of a similar size and type have sold for in the last year or two as both a multiple of sales and a multiple of their cash flow.

Then, there is an element of gut instinct. Valuations are part science, part art. Sometimes our models will come back with a number, and we automatically know that it is a little too low or little too high, and we adjust accordingly. All of these are weighted into an average, which results in the valuation. This is how most professional valuation firms will appraise companies. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), which certifies appraisers, follows this process as well.

Evaluating Customer Concentration Risk

With each sale or purchase, there is a threshold of both safety and risk. Some practices, on the surface, look identical. Maybe they have $1 million in revenue and $200,000 in cash flow, yet one might sell for $800,000 and the other might sell for $1.2 million. That is a big gap. One of the major factors that influences that gap is risk. The biggest element of risk in any business is customer concentration risk.

Customer Concentration Risk

Customer concentration risk exists when a small number of customers, or in our case patients, payers, or referral sources, generate a disproportionate amount of revenue. In audiology, we look at third-party payers, such as Medicaid and other insurance plans, and referral sources, such as referring physicians, nursing homes, or anyone else driving business to the practice. If they are generating a disproportionate share of your business, then it increases the risk of ownership, especially after transition, because there is no guarantee that this business will sustain in the future. If you lose a referral source or third-party payer, your sales, and ultimately your profits, will take a massive hit. Businesses that do not have customer concentration risk at all tend to sell for premiums to those that do, simply because they are less risky investments.

Payor Risk

Payor risk occurs in a practice overly reliant on third-party payers. There are two things to assess: the type of payor with which the practice is working and the percent of revenue. You can rank payers according to risk. Medicaid is the riskiest payer. If you are a heavy Medicaid provider and all of a sudden Medicaid is eliminated, you have just lost a steady stream of budgeted income. Private insurances, on the other hand, while risky, tend to be lower risk than states. They may be grandfathered into union contracts, and they typically pay more money for hearing aids than state agencies like Medicaid or vocational rehab programs.

Referral Source Risk

The other type of risk is referral source risk. It was common at one time for an audiologist to set up within or next to an ENT office and operate as that ENT’s audiology department, but the audiologist owns and runs it as their own business. A significant portion of their business is referred by those ENTs, and if those ENTs retire or decide they do not want to continue the relationship with the new owner, the business can suffer severely.

With referral source risk, you look at the percent of the business that comes from the referral sources, as well as the likelihood of transitioning the relationship to new ownership. If the new owner can enter some sort of contract or agreement with the referral source the same way the previous owner did, it is a much easier transition than a handshake agreement or no agreement at all. All of this gets factored into the valuation and weighted into even the discounted cash flow.

Case Studies

Case 1: Referral source risk

The first example covers referral source risk. We were working with a very profitable audiology practice with a single audiologist and one receptionist/office manager who worked about 32 hours a week. The practice generated around $650,000 in sales. That is highly productive when you consider the average audiologist working 40 hours a week generates $400,000 to $500,000 in sales. The owner was taking home between $260,000 and $280,000 a year. She rented space in a building owned by ENTs, and the ENTs were on a separate floor. The ENTs outsourced all of their audiology services to her, which represented 22% of her annual revenue.

The ENTs decided that they would not extend a lease to the new audiology owner because they want to bring audiology in house. She is trying to sell her practice and instantly the new owner loses 22% of annual new patients and has to relocate. As a by-product of this strong referral base, the owner did not spend much money on advertising. The new owner will have to drastically increase the advertising budget in order to compensate for this lost business and try to recover from sales, as well as announce a presence in a new location.

Fortunately, this practice is extraordinarily profitable. Frankly, this case blew up our valuation model because the cash flows were such a strong percentage of revenue. There was enough cash flow to still make the business sellable, even after all of this change took place. But it dramatically reduced the valuation. It literally cut the value of her practice in half, and she had to make a decision to sell or keep working until retirement or until she figured out another solution.

Case 2: Payor Risk

The second example is of payor risk. We worked with an audiology practice that served as a Veteran’s Administration (VA) provider. They were one of the overflow offices and saw a steady stream of VA patients on a weekly basis. Roughly 20% of their business came from the VA. The problem was that they did do not have a contract with the VA; they were just an authorized provider.

When trying to sell the practice, the buyer had to determine how to take over this authorization and ensure the business would still be coming in. If they purchased the assets of the company, they would have to go through a credentialing process again on their own, and they could potentially lose that business. This was the one deal that I have done in the last four years that was a stock purchase. The buyer ultimately decided buying the stock was worth the risk in order to maintain that business.

Case 3: Valuation Gap

The final example is of valuation gap. This was a smaller practice seeking a valuation of somewhere in the range of $400,000 to $500,000. The sales had been declining and the business was moderately profitable, but not profitable enough to justify that price that equated to one-times the sales. The buyer was valuing the business at around $250,000 to $300,000. How did we get a deal done? We came up with a creative structure that blended a payment at closing, a deferred payment, and an earnout. If the seller stayed on and worked for the buyer for a three-year period of time and maintained sales as they were historically, he would get close to that $400,000 number. If sales grew at a modest rate of about 5% a year, he had a shot to reach the full $500,000.

There was a huge gap in terms of what the seller wanted, and fortunately for the buyer, the business had been on the market for close to a year. The seller was realizing that there was no appetite for this purchase price. We came up with a creative solution that ultimately was advantageous if both the buyer and the seller continued to operate and grow the business; everyone would win, and the buyer would pay fair price for the business that met the seller’s expectations.

Conclusion

First, I would like to recommend that in any deal, always aim for a win-win outcome. There is a creative solution for every issue you run into. Both buyer and seller should walk away satisfied with both the price and the terms of the deal. Sometimes people get the impression that the sale of the business should be a knock-down, drag out fight where one side wins and one side loses. While that happens in the movies, the reality is that both sides can walk away with a favorable outcome.

The second take away is that there are several ways to calculate fair market value. Each has an appropriate application. One person could use multiple of sales and another could use discounted cash flow. One is not necessarily more correct than the other. We all have our own opinions, but you can get to an appropriate valuation several different ways.

At the end of the day, value must always be considered. A business is worth what someone else is willing to pay for it. If I want $1 million and the most someone is willing to pay for it is $900,000, the reality is the business is only worth $900,000.

Questions and Answers

What usually happens with accounts receivable and accounts payable in the sale?

Typically, there is an account cut-off at closing. The seller basically owns both the accounts receivable and accounts payable. The seller is responsible for paying all the bills and the seller has the right to collect all of the receivables. In the purchase agreement, you will draw up a schedule to itemize every receivable and payable so it is clear in the legal document what the seller’s responsibility is. As those payments come in, there are two ways to handle it. You can either have those payments directed to a bank account that the seller owns, or you would be a true-up after a 90-day period. You would figure out after the first 90 days after the sale, what does the buyer owe the seller and what does the seller owe the buyer for all the little things that have come up?

You talked about SDCF and EBITDA. Which is the preferred method?

It depends whether you are the buyer or the seller, and it depends on the size of the business. When you are dealing with larger businesses that have several million dollars in revenue, you would almost always use EBITDA on either side of the table. When you are dealing with smaller businesses, sometimes SDCF can be more applicable for two reasons. One reason is that for the seller it shows a greater profit figure. Another reason is that it demonstrates to a buyer how much cash flow is at their disposal. When you look at one small business selling to another individual, typically that person is buying a job. They are buying the business because they want to go in and operate it themselves. SDCF can be more relevant for them. If we are advising buyers, we typically recommend EBITDA. For the quiz question and for giving you a definitive answer, the answer is EBITDA. However, the reality is that it depends on the situation.

How do the number of years in practice and number of patient files influence the value?

It has an influence to a degree. A much more established business with a much larger file base presents greater stability and greater opportunity. However, once a practice is at least five to seven years old, especially when practices get to ten years old, they have been around long enough so that there is not much difference in the value of a 10-year old practice and a 40-year practice. The value is driven by the P&L and some of those key risk factors.

You may have a 40-year old business, but if you have some major customer concentration risk, you might not be worth as much as a 10-year old business that is more profitable and has none of the customer concentration risk. There should be more stability in a mature practice, which is seven years or older.

I think the other issue is analyzing the marketing strategy. If a seller has gone to the well and marketed to their database for the last three years to drive all their revenue, then your repeat business over predicted cash flow is going to different in the future because repurchasing habits do not happen in one or two years. There is more risk involved.

Is EBITDA usually the standard valuation for business? How does that number determine a selling price? Is it that number or a multiple?

It will be a multiple. We will use the EBITDA, which will be the primary input in a variety of calculations. There is no hard-and-fast rule of EBITDA, but you will see a general range; three to five times EBITDA is standard for smaller businesses, especially in sales to independent companies. We are looking at more than just applying the multiple to it.

There is more than one year’s worth of EBITDA. That would be a steep discount. It is usually at least three times the EBITDA as a safe floor for a price. You will want to have concurrent validity about a price. You should do multiple methods of evaluation, and there should be overlap in those prices. That overlap is likely the realistic price. If you are doing an EBITDA and the multiplier and then you apply your discounted cash flow, for example one price is $500,000 and the next is $475,000. The price should be traditionally between $475,000 and $500,000. The person should then analyze the risk involved along with the other opportunity costs or risk.

References

Feldman, S. J., Sullivan, T. G., & Winsby, R. M. (2002). What every business owner should know about valuing their business. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Cite this Content as:

Castelli, C., & Gleitman, R. (2015, February). Advanced transaction strategies, presented in partnership with the Academy of Doctors of Audiology. AudiologyOnline, Article 13417. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.