From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

AI is here! Some of you might recall, that a few months ago, our 20Q guest author was Dr. Josh Alexander, who provided an excellent review of how AI is being implemented in hearing aid processing, and in various fitting applications. We’re back talking about AI this month, but looking at a much bigger picture—how AI can impact our clinical services, and overall, the profession of audiology. To take us down this path, we’ve brought in an author who is known for looking at the big picture—Dr. Don Nielsen.

Dr. Nielsen points out that there is a need to solve several crucial problems, and these are influencing the application of AI to improve hearing health care. For example, we need to consider such issues as supply and demand (audiologists cannot effectively serve all the patients), affordability of services, access to hearing healthcare information, use of teleaudiology, and developing a wider application of hearing healthcare knowledge, just to name a few. Additionally, Don also discusses how AI “Precision Medicine” can be embraced by our profession. And there is much more!

Don Nielsen, PhD. is the Audiology University Advisor at Fuel Medical Group. Some of you might know him from his early days as a fundamental scientist, which lead to co-authoring the landmark textbook Fundamentals of Hearing—at one time, a required text in most audiology training programs. Over the years he has held leadership roles at major audiology centers, such as Henry Ford Hospital and the House Ear Institute, and also at several noted academic institutions, including the Washington University in St. Louis and Northwestern University.

Dr. Nielsen has earned membership in several prestigious organizations, including Psi Chi, the National Honorary Society in Psychology; Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society of North America; and the New York Academy of Sciences. He has had significant roles as a leader and board member of the Society of Research Administrators and the Association of Independent Research Institutes. Additionally, he is a charter member, former secretary-treasurer, and past president of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology.

So yes, as Don reviews, AI indeed is here and there are many applications that relate to audiology. Clearly, AI is not just for writing poetry anymore!

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Understanding the Artificial Intelligence Revolution in Hearing Healthcare Delivery

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Explain the basics of AI.

- Describe how AI will solve many of audiology’s most challenging problems.

- Discuss the basics of AI-driven precision medicine and genomics in the context of hearing healthcare.

1. I see headlines all the time about AI creating an intelligence revolution. What is that all about, and will it really affect me as a practicing audiologist?

Most certainly! The Intelligence Revolution refers to the massive transformation of society caused by the exponential growth of computer power and the unrelenting desire to create machines that do everything humans do. It is a profound revolution in how we think, work, and think of ourselves as humans. It is transforming our society, including the hearing healthcare (HHC) professions. Rest assured, the AI revolution is an ongoing process, not a sudden upheaval. It's a journey that we are all a part of, and understanding its origins and trajectory can help us confidently navigate the future of HHC.

2. Okay, what are AI’s origins?

Professor John McCarthy created the term artificial intelligence (AI) in 1956 when he gathered a small group to spend a few weeks brainstorming how to make machines do things like use language (Simonite, 2023). They failed, but they planted a fertile seed. AI, the ability of software to perform cognitive functions traditionally associated with human minds, became a new field of study. We have used AI for years when we talked with Siri or Alexa, searched the internet, or used a chatbot. However, basic AI could not generate original content. That came recently.

3. How in the world did they get a computer to think like a human?

They developed different models, each becoming more powerful and acquiring more cognition. With duplicating human cognition as their goal, not surprisingly, they attempted to duplicate how the brain works. They developed deep-learning-based models that use circuits and algorithms based on brain neural networks nested in layers, with connections between and among layers weighted differently as they train and learn. The first layer receives the input, and the last layer yields the output. But, just as scientists who study the brain don’t understand precisely how the brain works, the experts who create brain-replicating neural networks don’t always understand what happens in the neural networks they make. Deep-learning models excel at learning from text, images, audio, and code, from which they can produce new original text, images, audio, code, simulation, and videos. They can understand sequential data, such as how a word is used in a sentence and are drastically changing the way we approach content creation. That was an exception beginning but required human input. So, machine learning was developed.

Machine learning (ML) is a form of AI that can learn from data patterns without human direction. We train ML on an extensive database from which it detects patterns and learns how to make predictions and recommendations. Like humans, it also adapts, becoming more efficient with new data and experiences.

However, it was generative AI that allowed computers to generate original content. Generative AI (GenAI) is a form of machine learning based on deep learning and has more capabilities than basic AI. It can generate new content responding to a prompt by identifying patterns in massive quantities of training data and then creating original material with similar characteristics. Outputs from GenAI models can be indistinguishable from human-generated content. GenAI can be used out of the box or fine-tuned to perform specific tasks.

Large language models (LLM) are a type of GenAI, such as ChatGPT, trained exclusively on text. Because language allows us to build models of the world, even in the absence of any other stimuli, like vision or hearing, LLMs can write fluently about the relationships between different sounds even though it has never heard either.

The rapid growth of more powerful computers and the accompanying expansion of expertise will accelerate the use and capabilities of AI. Improved AI can help design even faster, more powerful computers. The Intelligence Revolution is on a fast track!

Integrating novel data and providing new services is crucial to healthcare AI development. As GenAI combines with HHC, we must shape it to solve critical problems in the HHC environment.

4. What would be an HHC problem that we hope to solve with AI?

There are many, more than you might think. The urgent need to solve these ten crucial problems plaguing HHC is heavily influencing the application of AI to improve hearing health care.

- Supply and demand: For the past two decades, approximately 800 new AuDs have graduated yearly, and the number of practicing audiologists has remained constant at about 12,000. The numbers for ENT physicians are similar. On the demand side, 40–60 million people in the US have hearing health issues, and the numbers are growing. Audiologists and ENT physicians cannot serve all the patients needing hearing health care. We must provide competent alternatives.

- Affordability: More than half the workers in the U.S. make less than $44,000 a year, and about 30% have no savings. Half the households of people 65 to 74 years of age have incomes less than $55,000, and half the households 75 and older have incomes less than $38,000. They cannot afford $5,000 once, much less every four or five years, for a pair of hearing aids. We must provide capable, low-priced hearing devices for those unable to afford traditional hearing aids.

- Information access: The traditional one-on-one in-person consultations we have relied on for creating and sharing HHC knowledge are outdated. The new view is that there is nothing so special or unique about a professional’s knowledge that we cannot make it easily accessible and understandable when delivered online. We must give patients easier access to HHC information and educate them on how to manage their hearing difficulties.

- The face-to-face dilemma: Patients prefer in-person interactions for their medical care (Singh & Dhar, 2023). But, in-person interactions are costly, and there are not enough providers to offer face-to-face care for everyone. We must reduce all unnecessary, expensive face-to-face interactions and simultaneously greatly increase overall accessibility.

- Psychological factors: Outsourcing a personal issue, including health issues, to another can be diminishing and conducive to doubts about one’s self-sufficiency. People gain satisfaction and self-respect when they grapple with problems on their own. We must provide information and tools that support the ability of individuals to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of an HHC worker.

- Moral obligation: Lack of affordability and access limits HHC in rural and economically challenged communities. There are places where no amount of money can get a human to come to help you with HHC. We have the technological means to spread HHC expertise more widely at a lower cost. As medical professionals, we must morally strive to make this happen.

- Need to improve medical care: We must move beyond the one-size-fits-all medical model and expand the boundaries of medicine beyond the traditional scope of clinical practice to deliver more precise, personalized and effective patient care.

- Need to improve collaborations with primary care providers (PCPs): HHC patients are more likely to seek and follow treatment recommended by their PCP. However, PCPs too often overlook HHC, and HHC providers too often ignore the importance of PCPs in HHC decisions. We must connect with PCPs and facilitate, educate and empower them to triage and refer HHC patients to the proper providers.

- Need for nonmedical HHC providers: Since we do not have enough medical providers to care for all HHC patients, we must create competent nonmedical providers for those patients who don’t require expensive advanced medical care.

- We need to expand clinical audiology to care for all HHC patients regardless of the severity of their hearing issues, including mild hearing loss and self-perceived hearing issues we miss, irrespective of their low profitability.

- Need for nonmedical HHC providers: Since we do not have enough medical providers to care for all HHC patients, we must create competent nonmedical providers for those patients who don’t require expensive advanced medical care.

5. That is an impressive list of HHC problems. Do you really think that they can be solved by GenAI?

To understand how GenAI is transforming the provision of HHC to resolve its problems, we must first appreciate the diversity of our patient base and their needs. This patient diversity and the multiplicity of needs, plus GenAI’s innovations and power, are the drivers of redefining HHC providers and transforming their roles. Here is where we stand today.

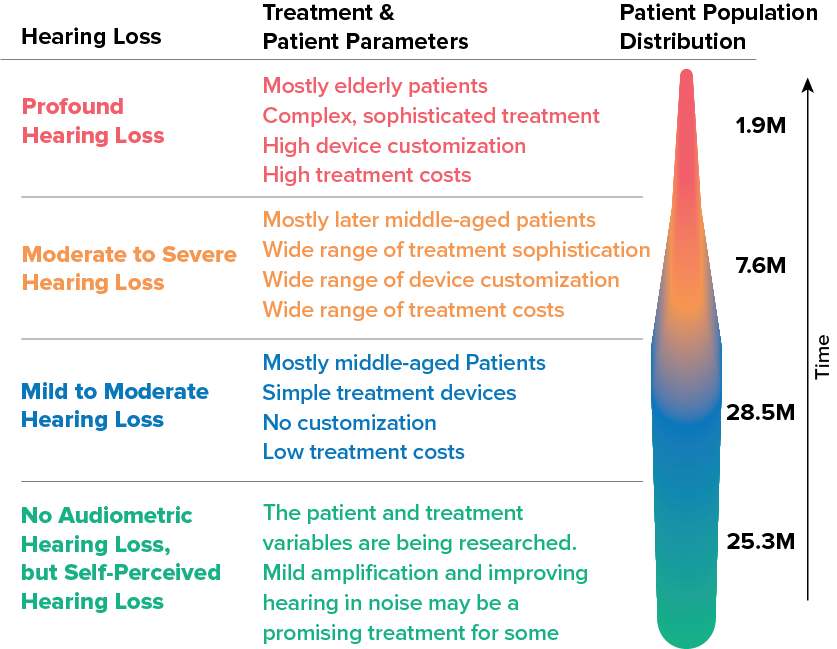

Figure 1. The distribution of patients according to their degree of hearing loss and the costs and quality of their treatments (Nielsen, 2024). Adapted from Taylor and Nielsen (2019), with data from Nash (2013), Lin (2011), Wallhagen & Pettengill (2008), Humes, (2021), and Edwards, (2020).

This figure illustrates that 75% of patients with measurable hearing loss have mild or moderate losses, while only 5% have profound hearing loss. There are overwhelming differences in the healthcare needs of these patient groups. Much hearing loss is chronic, and as time passes, the hearing loss gets more severe, so treatments and providers must evolve to accommodate those changes. Grouped by the severity of hearing loss, the illustration clarifies the differences in costs, treatments and expertise needed to serve each group.

Sadly, we have no established way to treat self-perceived hearing loss accompanying a normal audiogram. Mild amplification and improved hearing in noise show promise for some (Edwards, 2020; Roup, 2023). Mealings et al. (2023) reported that mild gain hearing aids can assist this population in having better self-reported hearing experiences in noisy environments. Still, differences were not observed in the laboratory tests. The increasing use of genomic diagnostics may give new insight into this issue. Indeed, no single treatment will work for all in this category, adding to the diversity of treatment complexity and costs.

The take-home message is that the provision of HHC for these groups differs drastically in the expertise required to treat them, treatment costs, and complexity.

6. But we already provide different treatments for these patients. How will this change with AI, and how will it be better?

Now we attempt to treat all these patients. That is inefficient and negatively affects access and affordability, GenAI reduces those problems by providing an array of providers that are custom-matched to the patient's needs. Here is how we do that:

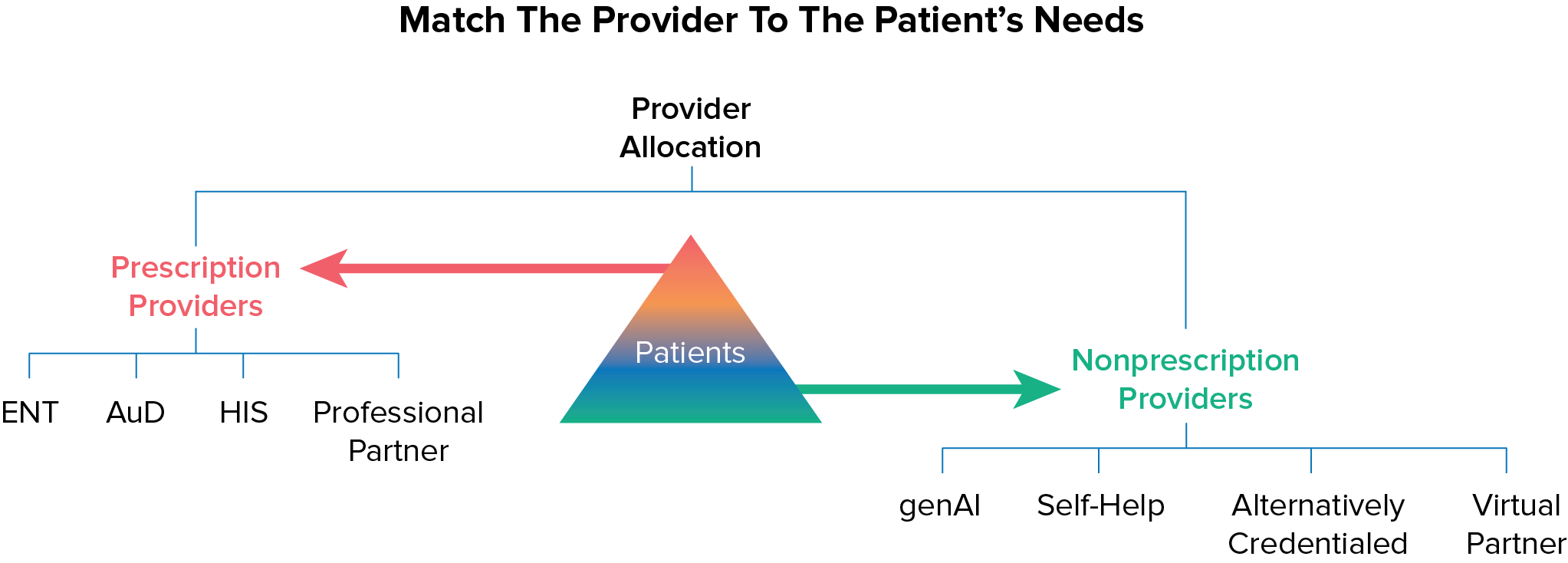

Figure 2. Patients in the upper portion of the triangle have complex prescription needs (see Figure 1) that are best met by providers using the medical model. Patients in the lower part of the triangle are best served by providers who do not use the medical model

This illustrates that we must split the diverse patient base (see Figure 1) into those requiring the medical model care (prescription providers) and those who will do well with nonmedical model care (nonprescription providers). The nonprescription providers GenAI, and virtual partners are created using AI. Self-help allows patients to care for themselves thanks to AI. Alternative credentialed providers are audiology extenders like Aud Techs. This triaging matches the patient’s needs to the appropriate provider and allows us to assign providers most efficiently and effectively while improving access and affordability. It also allows audiologists to focus on delivery to patients with complex prescription needs.

My assessment is that Audiology is at a turning point because we can now benefit from GenAI to efficiently address these diverse patient populations by matching patients’ unique needs with the proper level of care, thereby reducing costs and increasing accessibility.

7. Where would this patient triaging take place?

One of the most important places for this triaging to occur is at the primary care physician (PCP).

PCPs play crucial roles in HHC. PCPs are often the patient’s initial interaction point. They are responsible for identifying hearing loss in Medicare’s annual wellness exam. According to ASHA’s March 2021, You Gov Poll, a recommendation from a medical professional, particularly a PCP, is the most influential factor in a patient's decision to address their hearing health. Specifically, 42% of adults report that a recommendation from a medical professional would play the largest role in their decision to purchase a hearing aid, far outweighing other factors like cost (18%).

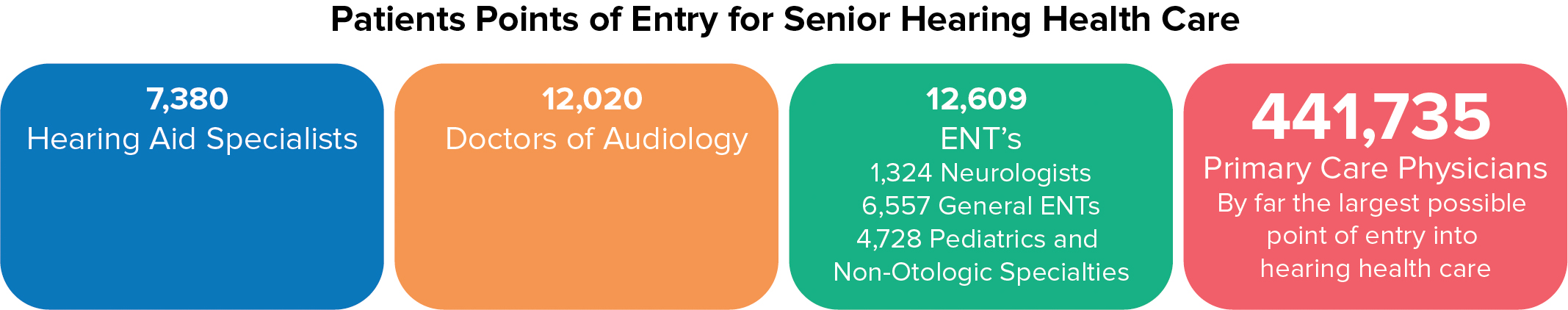

Figure 3. PCPs are the largest and most trusted entry point into senior HHC.

The problem with using PCPs is that HHC has not been a top priority for PCPs. Only 12% refer patients to hearing care, and many are confused or anxious about identifying the hearing health path their patients should follow. As a result, hearing issues can go undiagnosed and untreated or not seen by the optimum provider.

The AI solution: We can embed HHC-based AI in primary care annual wellness intake forms to identify more people with hearing issues, diagnose them correctly and guide them to the proper treatment device and provider.

8. Heavier involvement of the PCPs sounds critical to patient triage success. Is anybody doing this?

HCRpath, created by Sara Sable-Antry, provides us with an example of how AI embedded in a PCP’s intake forms provides a solution that benefits patients, PCPs, audiologists and ENTs. Here is how it works:

- HCRpath AI embedded in Medicare wellness exam intake forms identifies hearing loss and if the patient needs a medical exam.

- HCRpath considers a broad range of hearing devices, from simple nonmedical amplification devices to sophisticated medical devices, and matches the patient to the appropriate device suggestions based on its analysis.

- HCRpath considers several providers and suggests the most appropriate providers that the PCP could recommend to the patient.

In addition, HCRpath has several additional advantages, including audiologists and ENT physicians benefiting from more referrals for those patients genuinely concerned about hearing difficulties and ready to receive treatment. See www.hcrpath.com for more details.

This example demonstrates that AI embedded in the Medicare intake forms does not replace audiologists or ENT physicians. Instead, AI, as the PCP’s co-provider, makes informed decisions that guide only appropriate patients to their optimum providers, maximizing the providers’ time and services. In the future, this approach can benefit significantly from including genomic information and other personal information in the patient’s database and its integration into the intake form analysis.

To modernize the provision of HHC, a strong partnership between HHC providers and PCPs is necessary. AI can facilitate and strengthen that relationship. Audiology’s involvement adds credibility and sophistication. We must work toward integrating AI-enabled HHC in the PCPs domain. Audiologists and ENT physicians will gain from working with PCPs and their AI systems to be the clinicians or clinics the AI recommends.

9. Earlier you talked about hearing treatments that lend themselves to self-help. How will AI facilitate this?

One obstacle to improving patient access to information and promoting patient engagement in their health is our focus on treating illness instead of preventing it and underestimating the patient's importance. The common perception is that patients wait passively until they need medical attention and then consult a doctor.

However, with the help of GenAI, the expansion of innovations like remote self-hearing tests and wearable health monitoring devices allows patients to take charge of their healthcare by independently identifying and triaging medical issues, involving a doctor only when absolutely necessary. Simultaneously, there is a movement towards bringing GenAI-driven personalized medical devices from medical practices to residential settings. Even cochlear implant recipients can self-test at home to monitor implant performance with smartphones or tablets (Wasmann et al., 2023).

Because of these changes and the imbalance between the availability of providers and the demand for their services, people are now managing their hearing health for the long term. Recognizing patients as empowered individuals in managing their health transforms them into active contributors to the medical process. It acknowledges that the individual may possess unique knowledge, motivation, or influence that others or institutions may not have. The medical community's role and its institutions are not diminished. Hartenstein and Latkovic (2022) suggest that self-help enhances efficiency.

10. Can virtual providers adequately deliver this patient care?

GenAI allows us to provide accessible, competent virtual providers instead of one-on-one in-person medical care when patients need constant or repetitive instructions. The AI that empowers virtual providers and self-help assistance is often the same. We call it telepresence.

Telepresence is a technology that allows people to feel as if they are physically present with someone whom technology represents digitally. In prescription HHC, telepresence can be an essential part of digital therapeutics (DTx) to treat and manage diseases. DTx are patient-facing software applications that help patients treat, prevent, or manage a disease and have a proven clinical benefit. Given the widespread use of cell phones and computers, telepresence is rapidly evolving to strengthen health care and increase affordability and accessibility.

11. How is telepresence an improvement from previous technologies?

Previous virtual technologies, like Internet chat blogs, were not lifelike or personal—questioning and answering required laboriously written interactions with long delays, frustrating misspellings, and mistaken interpretations. Notably, the elderly find them challenging and unnatural.

Videos are an improvement over text-based chatbots; however, if you have assembled furniture while watching a YouTube video, you understand the limitations of the video instructional model. Self-help videos give limited instructions, lack interactions, and are often problematic.

AMIE is a telepresence-style chatbot created before GPT-4o to provide medical advice to patients. It was compared to human doctors to assess its ability to show empathy and engage in conversations. AIME performed better than doctors in 24 out of 26 aspects of conversation quality, offering patients an equal or higher level of empathy and support as human physicians (Haseltine, 2024).

Virtual providers using GenAI, like AIME, can learn, converse, and problem-solve like humans. Still, with the advent of GPT-4o, they can do better because GPT-4o is natively multimodal, which means it can “see,” “hear,” and “speak” in an integrated way with almost no delays. It can blend all of these modes together. It can see what you are doing, react to it, respond to interruptions, use realistic voice tones, and create images. Virtual providers can react like humans and influence patients as humans do (Mollick, 2024). GPT-4o is free. Experiment with it to discover its many attributes and imagine its use with 3D virtual providers. Virtual providers can exceed routine human communication by using captioning, clear speech, synced in—focus, and accurate lip movements. They have quickly evolved to be competent coworkers.

12. Telepresence sounds promising, but real clinicians can react to patients’ emotions. Can telepresence do that?

Contrary to popular belief, AI can express emotions by reacting to the feelings of others. GenAI-based systems can determine a patient’s emotional state by analyzing speech patterns and other cues, such as facial expressions and physiological measures. These systems can help inform a virtual provider in real time if the patient is or is not engaged and what material is resonating. The virtual presenter could slow down, show more empathy, or make other changes. Patients will develop relationships with virtual providers as they do with friendly front office staff and human providers.

13. In general, you think that GenAI will benefit hearing healthcare delivery?

Most certainly. Gen AI facilitates the development of new care delivery capabilities that fundamentally change how HHC teams spend their most valuable resource: time. Now, we can provide patients with needed information 24/7 from a virtual person who analyzes vast amounts of patient data, answers any GenAI verbal or written questions, and presents a pleasant, empathetic personality. As the virtual partner acquires more knowledge, it improves with use.

14. Let’s jump to the topic of OTC hearing aids, which are receiving considerable attention. Will GenAI and telepresence play a role in OTC delivery and acceptance?

By allowing patients to feel as if they are physically present with someone whom technology represents digitally, telepresence can transform over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aid adoption. The FDA promoted OTC hearing aids to provide high-quality hearing aids that people with mild to moderate hearing loss could buy online or at local pharmacies and big-box stores without the assistance of a professional.

However, acquiring hearing aids over the counter can still feel challenging. Not everyone with hearing loss is comfortable with online sales or do-it-yourself adjustments via apps. ASHA’s OTC Hearing Aid Survey, 2023, found that only 24% of patients who were at least somewhat confident that an OTC device could assist them were satisfied they could choose the correct one. They need help.

AI-enabled platforms could be the key to adopting more excellent value-based care options. Consider how helpful interactive dialog with a quality virtual provider could be in informing patients about OTC devices. Patients could discuss if the devices are appropriate treatments for their hearing issues. If so, they can also get suggestions about which OTC device to purchase and how to unbox, fit, and maintain it. This system would introduce patients to HHC in a less expensive, more accessible, more prosperous, and more rewarding way than it currently does.

Perhaps the ultimate telepresence innovation is Google’s Project Starline, which, without the need for 3D glasses, provides the patient with a life-sized 3D image across the table from them:

www.youtube.com/ watch?v=obuyCkotJ_s. No more flat, boring screens! The image is so lifelike that people try to reach out to each other to shake hands or fist bump. That 3D image could be a virtual representation of their personal physician or audiologist equipped with precision medicine knowledge, sensitive to the patient’s emotions, and available 24/7 for consultation.

The more true-to-life experience of 3D and holographic medicine is already with us. The University of Central Florida, see: healthprofes-sions.ucf.edu/rehabilitation-innovation-center/#contact, uses holograms to train students and educate patients.

Virtual reality headsets are like having a computer strapped to your face. In time, these headsets will be inexpensive enough for healthcare systems and insurers to provide them so their patients can consult with a 3D virtual healthcare provider 24/7, creating a massive transformation in healthcare.

AI-powered virtual health care has the potential to be both convenient and cost-effective. Patients no longer need to schedule appointments, travel to a healthcare provider, or wait for an in-person, one-on-one meeting with their provider.

15. You have concentrated on remote virtual providers as audiology extenders. Can GenAI also provide audiology extenders in the clinic to free up and reallocate AuD time?

While self-help and remote virtual providers will improve HHC access, in-office AI-enabled providers like AMTAS Pro must accompany prescription care.

AMTAS Pro: This is made by GSI and provides an Automated Method for Testing Auditory Sensitivity. It is an in-office patient-directed hearing assessment tool that uses AI to obtain diagnostic or screening audiometry. Imagine the benefits of freeing up the time to perform complete diagnostic testing.

AMTAS Pro is self-paced, so patients may proceed at a rate that is comfortable for them. A complete diagnostic evaluation will typically take 15–20 minutes for the patient to complete independently, which provides more time for the audiologists to attend to other patients.

Audiology extenders are essential in freeing audiologists from routine testing tasks to reallocate their time to the most complex patients who can only succeed with audiologists participating in their HHC. In-office AI-enabled audiology extenders fulfill this role while reducing costs.

16. Earlier you listed several HHC problems you expected GenAI to solve. Now that I understand a little more about AI's abilities, what are your thoughts on how AI will solve those problems.

AI can benefit HHC, but HHC must change to reap the benefits and solve HHC’s problems. Since you asked, for each HHC delivery problem, here is the AI solution.

- Supply and demand: Audiologists and ENTs cannot serve all the patients needing hearing health care. We must provide competent alternatives such as:

- Audiology assistants

- Additional audiology extenders

- Accessible AI-driven virtual providers using captioning and clear speech and eventually being 3D and with access to precision medicine knowledge

- Working with researchers and manufacturers to perfect AI-enabled virtual healthcare

- Affordability: We must provide capable, low-priced hearing devices for those unable to afford traditional hearing aids.

- Participate in vetted OTC hearing aid sales using virtual AI providers to understand the patient’s needs, recommend the best device and assist in fitting and maintenance.

- Use OTCs to attract patients with mild losses to your practice. Monitor their hearing, knowing that their hearing issues will increase for many.

- Participate in research to improve and promote OTC treatments and virtual nonprescription HHC provision.

- Information access: We must give patients improved access to HHC information and educate them on how to manage their hearing difficulties.

- Provide accessible online AI-enabled virtual educators so customers know where they are in the patient triangle and where they should seek care.

- Use AI-driven self-help assistants to aid in fitting and maintaining nonprescription treatments.

- Provide online HHC education services to your local PCP groups.

- The face-to-face dilemma: We must reduce all unnecessary, expensive face-to-face interactions and simultaneously significantly increase overall accessibility.

- Use AI to triage patients to match their needs with the proper providers so only those needing doctoral-level expertise see doctors.

- Use appropriate audiology extenders or virtual providers to treat nonprescription needs and instruct them on using self-help.

- Psychological factors: We must provide information and tools that support the ability of individuals to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of an HHC worker.

- Use the internet, telepresence, and AI virtual representation to educate, promote, and facilitate self-help.

- Moral obligation: We have the technological means to spread HHC expertise more widely at a lower cost. As medical professionals, we must morally strive to make this happen.

- Include the whole spectrum of patient needs in your practice.

- Use AI to match patient needs with the appropriate level of expertise and support self-help when appropriate.

- Maximize care to match patients’ limited finances.

- Create innovative solutions to lower costs to the patient.

- Need to improve medical care: We must expand medicine's boundaries beyond the traditional scope of clinical practice to deliver more precise, personalized, and effective patient care.

- Move beyond the one-size-fits-all medical model.

- Establish holistic care in your clinic.

- Actively participate in precision medicine.

- Educate your clinicians about the importance of related professions like genomics and their relation to HHC.

- Need to improve collaborations with primary care providers (PCPs): We must connect with PCPs and facilitate, educate, and empower them to triage and refer HHC patients to the proper providers.

- Work with local PCPs to educate them about the importance of HHC.

- Support PCP active triaging of HHC for seniors.

- Volunteer to participate in joint experimental patient triaging with PCPs.

- Need for nonmedical HHC providers: We must create competent nonmedical providers for those patients who do not require expensive advanced medical care.

- Train and hire audiology assistants.

- Increase accessibility to virtual providers.

By directing the appropriate patients to new GenAI-equipped channels to diagnose and treat their nonprescription HHC needs, GenAI will streamline patient triage so only those needing qualified prescription-capable providers will see physicians and audiologists. This liberation of prescription providers will result in more patients with prescription needs being appropriately seen and treated, significantly improving HHC.

GenAI-driven precision medicine also increases the power and scope of prescription providers by allowing them to analyze enormous datasets, glean hitherto unavailable relevant information, and research that information to make patient-personalized diagnostic and treatment decisions. Because of GenAI, precision medicine can revolutionize the provision and delivery of prescription HHC. For an introduction to precision medicine, see Nielsen (2024). I explain it in more detail in an upcoming new Fuel Medical Group white paper, “Genomics and Precision Medicine: The Astonishing Reinvention of Hearing Healthcare.”

17. You make it sound like AI is transforming the medical paradigm beyond telepresence and virtual providers.

It is! Because AI can swiftly uncover difficult-to-discern patterns in massive quantities of data, it is revolutionizing health care.

GenAI is the driving force behind significant changes in the medical care paradigm. The traditional approach of treating the “average” patient with a one-size-fits-all model has proven ineffective, leading to misdiagnosis and suboptimal treatment outcomes (Cerrato & Halamka, 2023).

GenAI-enabled precision medicine has emerged as a revolutionary healthcare diagnosis, delivery, and treatment approach. It provides the mechanism to transform healthcare, improving its quality, consistency, and efficiency.

Precision medicine offers a more personalized, precise, and effective approach to clinical practice, representing a change in basic assumptions from conventional medicine. It addresses the inherent problems of one-size-fits-all treatment and provides an antidote. It even addresses timely medical issues, such as inequality emanating from how health care is currently defined and investigated (Tinetti et al., 2023).

Put concisely, GenAI’s ability to analyze massive data sets that are too complex for human cognition has given life to precision medicine.

18. You’ve mentioned “Precision Medicine” a few times. I’m not exactly sure what this is.

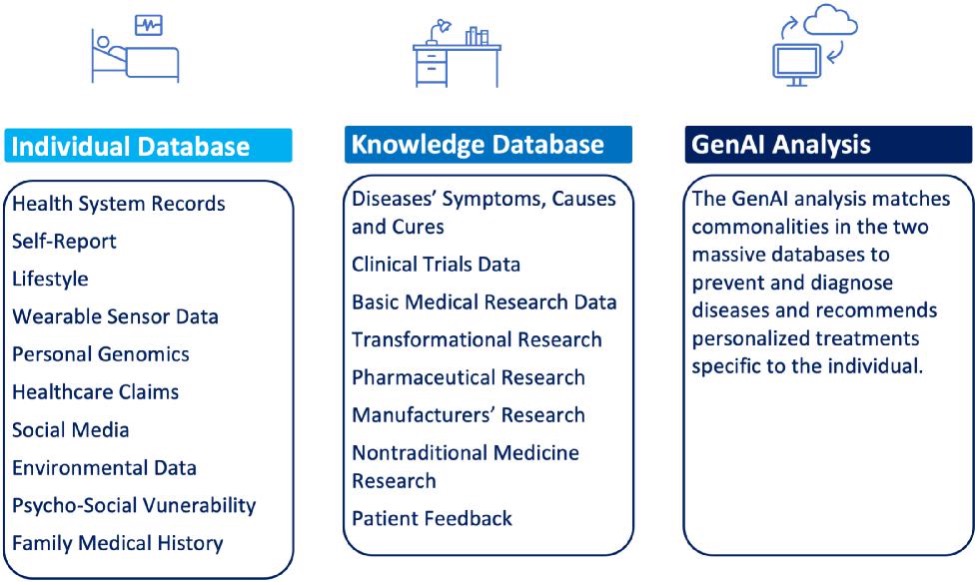

A precision medicine-based medical system collects two giant data sets, one about the individual and the other about the disease mechanisms, and, without human direction, analyzes them, detecting patterns and making predictions and recommendations to deliver personalized patient care.

Cerrato and Halamka (2023) of the Mayo Clinic explain that precision medicine, the new medical model, equips every patient who walks into a medical office with a comprehensive collection of relevant medical data. “That includes their complete genome with all the mutations that increase their risk of specific diseases, genetic variants that make them susceptible to drug toxicity, all their environmental exposures to toxins and allergens, along with their clinical chemistries, medical and family histories, psychosocial vulnerabilities, nutritional deficiencies and much more. And once these data are available, we want to see precisely designed treatment protocols to address these problems.”

Figure 4. AI-enabled precision medicine. AI-driven precision medicine integrates the investigation of disease mechanisms with prevention, treatment, and cure at the individual level, providing high-value, personalized health care that improves outcomes while decreasing costs.

19. You’ve talked about genomics, which I assume is closely related to genetics.

Yes, genetics primarily examines individual genes and their functions, whereas genomics takes a more comprehensive approach by exploring an organism's complete genetic composition and studying how genes interact with one another and the surrounding environment. Emphasizing genomics is a distinctive and crucial strength of precision medicine. Precision medicine is enabled by the power of GenAI to analyze massive amounts of genetic information and apply that information to customize the individual patient’s diagnosis and treatments. For audiologists, genomic data is rarely available. HHC providers are seldom well versed in the genomics of hearing loss, even though genetic hearing loss accounts for 50% of congenital sensorineural hearing loss (Young & Ng, 2023). The remaining hearing loss cases are due to aging, environmental or acquired causes such as infection, trauma, noise exposure, and ototoxicity that also may have genetic components.

The healthcare potential and low sequencing costs of AI-enabled genomics will cause an individual’s genome to be as much a routine part of the medical record as their blood work.

The cost of sequencing an individual genome has decreased from $3 billion to less than $100 in the last 20 years, unlocking the full potential of the human genome. Sequencing allows a doctor to identify differences between a patient’s sample and the reference genome. This helps determine a patient’s genetic disease or helps doctors look across a population to discover new drug targets (Vacek, 2023). HHC must actively expand the use of genomics in this enduring AI-driven healthcare transformation.

Properly diagnosing hearing loss must include all genetic and acquired causes; AI and precision medicine enable us to do that.

Let’s consider “Genetic Scissors”. An increased emphasis on genomics will extend its benefits to HHC. Gene-editing technologies like CRISPR are becoming available for many diseases. This technology acts like a pair of molecular scissors to cut and modify a DNA sequence. Initially, CRISPR therapies required a complex and lengthy procedure, much like a stem cell transplant. However, we can now deliver these therapies directly to the patient. Gene editing will allow us to rewrite HHC-relevant portions of the genome. With base editing, we can even change a single base in the genome without damaging the DNA molecule. This revolutionary technology permits us to target the root cause of the disease and potentially cure the patient even before symptoms exist. Gene-editing drugs cost $1–2 million, but like the cost of sequencing, the price will decrease sharply. Traditional drug treatments must be repeatedly administered and are subject to interactions with other drugs. Genetic solutions are cures expected to last a lifetime. Genomics and gene editing will play a crucial role in the future of HHC.

Thanks to AI, precision medicine promises to improve health care significantly, but it also has challenges.

The fundamental challenge is the assimilating, analyzing and integrating genomic data, electronic medical records (EMRs), data obtained with mobile health devices and other data on millions of people.

Another essential challenge is ensuring appropriate participant inclusion regarding ethnic diversity and other demographics and the inclusion of the medically disenfranchised without EMRs or ready access to the Internet.

Finally, it must address privacy and security concerns.

20. With all the information you’ve provided, I have to ask: Why aren’t these new innovations and technologies being more rapidly accepted into hearing healthcare?

Believing that tomorrow will be similar to today is a deep-seated human bias, as it is typically true. However, not at this moment! Yesterday’s traditional methods did not provide the personalized quality care we can now begin to provide.

The fields of GenAI, genomics, precision medicine, and computer-driven big data analysis/systems are all flourishing and advancing simultaneously. These combinations of innovation and technology offer HHC providers multiple new, better, and more competitive options for the future.

The assumptions we have traditionally based the HHC profession on, which dictate decisions about what to do, who does it, and what not to do, will no longer fit our new AI-enabled reality.

We have the power to improve audiology in the decades to come and in ways we cannot even imagine now. To achieve growth and success, audiology must abandon outdated practices from the 1900s and embrace new delivery methods that take advantage of rapidly evolving opportunities to effectively treat more patients, deliver improved care, and provide hope, optimism, and a viable strategy for the future of hearing healthcare.

References

Cerrato, P., & Halamka, J. (2023). Redefining the boundaries of medicine: The high-tech, high-touch path into the future. Mayo Clinic Press.

Edwards, B. (2020). Emerging technologies, market segments, and MarkeTrak 10 insights in hearing health. Seminars in Hearing, 41(1), 37–54.

Haseltine, L. (2024). Medical artificial intelligence: A new frontier in precision medicine. Inside Precision Medicine, February, 46–49. http://www.insideprecisionmedicine.com/topics/informatics/medical-artificial-intelligence-a-new-frontier-in-precision-medicine/

Humes, L. E. (2021). An approach to self-assessed auditory wellness in older adults. Ear & Hearing, 42(5), 745–761.

Lin, F. R., Niparko, J. K., & Ferrucci, L. (2011). Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(20), 1851–1852.

Mealings, K., Valderrama, J. T., Mejia, J., Yeend, I., Beach, E. F., & Edwards, B. (2023). Hearing aids reduce self-perceived difficulties in noise for listeners with normal audiograms. Ear and Hearing, 45(1), 151–163. doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000845

Mollick, E. (2024, May 14). What OpenAI did. One Useful Thing [Substack]. https://oneusefulthing.substack.com/p/what-openai-did

Nash, S. D., Cruickshanks, K. J., Huang, G. H., et al. (2013). Unmet hearing health care needs: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(6), 1134–1139. doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301030

Nielsen, D. W. (2024). The intelligence revolution in hearing healthcare delivery. A Fuel Medical Group Publication. https://fuelmedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/intelligence-revolution.pdf

Roup, A. (2023). Middle-aged adults with normal audiograms and self-reported hearing difficulties: How research informs care. Hearing Health Matters. https://hearinghealthmatters.org/thisweek/2023/normal-hearing-noise-difficulty-roup/

Simonite, T. (2023, February 8). The Wired guide to artificial intelligence. www.wired.com/story/guide-artificial-intelligence/

Singh, J., & Dhar, S. (2023). Assessment of consumer attitudes following recent changes in the US hearing health care market. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2022.4344

Taylor, B. S., & Nielsen, D. W. (2019). Entrepreneurial audiology: Sales and marketing strategies in the consumer-driven health care era. In B. Taylor (Ed.), Audiology practice management (3rd ed.). Thieme Publishers.

Tinetti, M. E., Hladek, M. C., & Ejem, D. (2023). One size fits all—An underappreciated health inequality. JAMA Internal Medicine. doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.6035

Vacek, G. (2023). How AI is transforming genomics. NIVIA Blog. https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/2023/02/24/how-ai-is-transforming-genomics/

Wallhagen, M. I., & Pettengill, E. (2008). Hearing impairment: Significant but underassessed in primary care settings. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 34(2), 36–42.

Wasmann, J. W. A., Huinck, W. J., & Lanting, C. P. (2023). Remote cochlear implant assessments: Validity and stability in self-administered smartphone-based testing. Ear and Hearing, 45(1), 239–249. doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000934

YouGov & American Speech Language and Hearing Association. (2021). Attitudes and actions towards hearing health: Summary report of U.S. adults ages 18+. www.asha.org/siteassets/bhsm/2021/asha-bhsm-2021-report.pdf

Young, A., & Ng, M. (2023). Genetic hearing loss. National Library of Medicine. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580517

Citation

Nielsen, D. (2024). 20Q: Understanding the artificial intelligence revolution in hearing healthcare delivery. AudiologyOnline, Article 29121. Available at www.audiologyonline.com