From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

So, you just finished a busy day of fitting hearing aids—all new hearing aid users. The patients, as usual, varied somewhat in age, personalities, and degree of hearing loss. Fortunately, your schedule allowed you to spend enough time with each to cover what seemed to be adequate orientation and counseling for the day-of-the-fit.

You’re giving yourself a little pat on the back, as in all cases, your fittings were quite close to NAL-NL2 targets, the MPO was adjusted to just the right level, and your unaided vs. aided QuickSIN testing gave those patients a good “shot-in-the-arm,” showing that hearing aids really do work in background noise. All is well. Or, maybe not. You know that there’s a good chance that one of those patients probably won’t be a happy hearing aid user . . . at least not initially. Why? It’s complicated.

Most individuals obtaining hearing aids for the first time have had hearing loss for several years, and during this time many social and emotional factors come into play. Research has shown that commonly reported experiences include social overwhelm, isolation, frustration, fatigue, exclusion, conflict with significant others, sadness, and disappointment. Many of these factors won’t simply go away when a pair of hearing aids are fitted. Helping the patient work through them is all part of the fitting process.

We’ve brought in an expert this month to give us some guidance on how to accomplish this. Bec Bennett, PhD, is a Senior Research Audiologist at the National Acoustic Laboratories, and holds Senior Adjunct roles with the Ear Science Institute Australia, Curtin University and the University of Queensland. She has a special interest in the social and emotional impacts of hearing loss and the role of the audiologist in supporting the social and emotional wellbeing needs of adults with hearing loss, and has published extensively in this area.

Through the recent award of an NHMRC Investigator Grant Fellowship, Dr. Bennett is now developing an mHealth intervention targeting listening fatigue, social connectedness and social anxiety in adults with hearing loss. She also recently has been involved in developing a program called the AIMER, which stands for Asking, Informing, Managing, Encouraging, and Referring. It's designed to help audiologists address social-emotional well-being needs in their practice.

Her many contributions have led to numerous honors and awards including the Finalist of the Premier Science Award - Woodside Early Career Scientist of the Year, Curtin Research Excellence Award, and Consumer and Community Involvement award for SWAN. She is a Director on the Board of Audiology Australia and Chairs the Australia Teleaudiology Clinical Guidelines Development group.

As you’ll see in her excellent 20Q, Bec not only provides the background to help us better understand the social and emotional needs of our patients, but she also includes some very useful tips on how we can improve our clinical skills in this area. I can pretty much sum up her general theme using one of her own sentences: “We can’t add years to their lives, but we can add lives to their years.”

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Social and Emotional Impacts of Hearing Loss—Empowering Audiologists

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Describe how hearing loss can impact on a person’s social and emotional wellbeing.

- List common strategies employed by people in an attempt to cope with the social and emotional impacts of hearing loss, both maladaptive and supportive coping strategies.

- Describe the key components of the AIMER program and how they support audiologists to support the social and emotional needs of their patients.

1. If my memory is correct, recently, you’ve been conducting research on the social and emotional impacts of hearing loss?

That’s correct. This area of research became my passion during my days in the clinic. I noticed that while some people did exceptionally well with hearing aids, enabling them to hear adequately to excel in work and social environments, other patients with virtually the same audiograms would experience ongoing social disconnection even with regular hearing aid use. They shared their struggles with feeling left out of conversations, even though their hearing aids were set to prescriptive targets. They would describe attending busy social functions and feel like they could hear better, but then begin to feel fatigued and leave the party early. Some would mention how they used to participate in activities like Rotary, book clubs, or knitting circles but now felt too overwhelmed to give it another try, despite having acquired hearing aids. These experiences got me thinking about the role of the audiologist in helping people address these challenges.

2. What do you think is going on here?

We know that hearing loss can be quite insidious. People often experience a gradual decline in their hearing over a long period of time, and as we know, it can take around 5 to 10 years for them to fully recognize and appreciate the extent of their hearing difficulties and then to take the step of seeking help from an audiologist. During these years of slow and gradual hearing decline, individuals may develop maladaptive coping strategies. By maladaptive strategies, I mean that when they encounter hearing difficulties, they may withdraw socially, refrain from asking for repeats, and avoid certain people or situations that are notoriously challenging to hear in. These are not really the outcomes that we like to see. However, it's important to acknowledge that there are things people can do to address these issues. This is where the role of the audiologist comes in - to help individuals find solutions beyond just hearing devices.

3. Can you tell me more about the social and emotional issues people with hearing loss face?

Absolutely. As part of one of our research projects, we interviewed adults with hearing loss to explore the social and emotional impacts they experience (Bennett et al., 2022). The findings revealed a wide range of experiences. Participants described emotional distress related to their hearing loss across various categories. The most commonly reported experiences were social overwhelm, frustration, fatigue, loss, exclusion, conflict with significant others, sadness, and disappointment.

I want to say a bit more about some of these. The first one I mentioned was social overwhelm. This is where individuals feel that things are too much to handle, they lack the power to change their circumstances, and they become passively disengaged. Many of the people we interviewed reported this.

Fatigue was also commonly reported and encompassed both listening fatigue and the exhaustion of having to take responsibility for organizing events and controlling situations to ensure equitable access to conversations. Feeling of loss was another cognitive representation of their experiences, capturing the realization that they were missing out on parts of conversations, experiences, connections, and life itself.

Exclusion was an emotional consequence of being left out of events and conversations, while frustration manifested as feelings of grumpiness, annoyance, or irritability towards themselves and others. Grief emerged as a response to missing out on things and a shift in identity due to the loss of aspects of oneself. Anxiety also arose from the stress caused by communication challenges associated with hearing loss.

Loneliness was a significant emotional consequence, reflecting the inability to socially and emotionally connect with loved ones. Lastly, burdensomeness was described as an overwhelming sense that their hearing loss placed unnecessary negative pressure on their loved ones.

Our research findings highlighted the profound social and emotional impacts faced by individuals with hearing loss. It underscores the importance of addressing not only the physical aspects but also the psychological and emotional well-being of individuals with hearing loss.

4. That's really eye-opening. I would guess that they employ various coping strategies?

Yes, we found that they described a range of coping mechanisms that they used to manage the emotional distress caused by their hearing loss. We summarised these into four different types of strategy: avoidance, solution-focused approaches, seeking support, and cognitive reappraisal.

Avoidance was a common coping strategy, with participants describing both helpful and unhelpful forms of avoidance. Helpful avoidance involved selectively removing oneself from difficult situations to regain energy, while unhelpful avoidance referred to giving up on things and avoiding them due to the emotional difficulty of the environment.

Solution-focused coping strategies focused on controlling the listening environment to improve hearing capabilities, but participants also acknowledged the fatigue and pushback they sometimes faced in implementing these strategies.

Humor emerged as a positive coping mechanism for some, with individuals making light of themselves or the situation to disarm or cope with emotionally charged situations. However, we need to also be aware that the use of humor by others can be hurtful and can exacerbate feelings of stigma association with hearing loss. Humor can be a double-edged sword in this respect.

Seeking support was another coping strategy, with participants displaying assertiveness in social situations by asking for repeats, making their hearing loss known, and addressing negative behaviors from communication partners. They also emphasized the importance of accepting support from significant others and recognized the value of support groups comprised of individuals with similar experiences.

However, we observed that many participants lacked effective coping strategies and primarily relied on avoidance, which tended to amplify their underlying distress rather than resolve it. Many participants expressed their desire to have coping strategies to address specific distressing experiences, such as frustration, exclusion, conflict with significant others, sadness, disappointment, and embarrassment. Participants specifically described wanting strategies to help them cope with missing out on being able to participate in social interactions and specified that they wanted their audiologist to facilitate the development of these skills. They expressed disappointment that these services were not provided within the hearing healthcare services that they received.

These research findings underscored the importance of audiologists in facilitating the development of coping skills for individuals with hearing loss. By providing targeted support and guidance, audiologists can help individuals employ more effective coping strategies, enhance their emotional well-being, and improve their overall quality of life.

5. It's interesting to see the range of coping mechanisms. What are the consequences of people not having helpful strategies?

While some participants described how their coping strategies assisted them in managing specific situations, there were negative consequences associated with certain coping strategies. It's important to note that these consequences were not directly caused by the hearing loss itself but rather by the emotional distress experienced as a result of the hearing loss.

For instance, avoidance strategies had detrimental effects on employment and overall enjoyment in the workplace. One participant shared her experience of giving up work due to her hearing loss. She described how her hearing loss made it challenging for her to participate in meetings, leading to feelings of unprofessionalism and a significant blow to her self-esteem. She described her decision to retire early as “life-shattering.”

Interestingly, in some cases, the emotional distress spurred individuals to adopt solution-focused behaviors related to managing their hearing loss. For example, one participant who was a teacher gave up teaching because of the difficulties she faced in hearing the students in her class. However, this experience motivated her to seek help and find out what was wrong with her hearing. She recognized the negative impact on the classroom dynamic and her own frustration when constantly asking students to repeat themselves, leading to their own embarrassment and decreased engagement. This spurred her to acquire hearing aids, use them, and find a new role within the school that was better suited to her needs.

These examples highlight the far-reaching consequences of not having helpful coping strategies for individuals with hearing loss. It not only affects their self-esteem and professional opportunities but also impacts their overall emotional well-being and interactions with others. It emphasizes the need for effective support and guidance to help individuals develop positive coping strategies and overcome the challenges associated with their hearing loss.

6. What role do audiologists play in helping people with maladaptive coping strategies?

I believe there's a missed opportunity for audiologists in addressing the social and emotional impacts of hearing loss. In Australia, the first audiologists were actually trained psychologists who provided not only hearing aids but psychological intervention for coming to terms with and adapting to life with hearing loss.

However, over time, our focus has shifted more toward the technological aspects of hearing devices. Yet, there are many cases where hearing aids alone are not sufficient to address the full range of impacts hearing loss has on someone's life. Audiologists are in a unique position to provide holistic support, considering the impacts of hearing loss on social, emotional, relational, and occupational aspects of an individual's life.

In fact, we need to acknowledge the changing landscape where devices are becoming increasingly automated and self-programmable hearing aids are more prevalent. As these technologies advance, our role as audiologists cannot be solely reliant on providing hearing devices. If we limit ourselves to that, our future might seem bleak. However, if we embrace a role that is comprehensive, taking into account the individual's ear and hearing conditions and adopting a holistic view of evaluating the impacts of hearing loss on their well-being, we create a multifaceted and indispensable role for ourselves.

By exploring how hearing loss affects not only their hearing function but also their relationships, their social and emotional well-being, workplace performance, and financial capacity, we position ourselves as experts who provide far more than just hearing devices. We become partners in addressing the diverse needs of individuals with hearing loss, offering personalized support and guidance that goes beyond what can be obtained online or through self-fitting.

7. I like your vision, but the obvious question is, do our patients really want this?

Yes, absolutely 100%! All the focus groups and interviews we've conducted with hundreds of adults with hearing loss over the past five years have unequivocally expressed their belief that the role of the audiologist should encompass the consideration of social and emotional impacts of hearing loss. They want audiologists to validate their experiences, see them as they are, and help them understand and address the many ways in which hearing loss impacts their lives.

Interestingly, during our group discussions, a question was raised about whether this role should be fulfilled by a GP or a psychologist instead. However, without a doubt, the adults with hearing loss and their significant others who participated in these discussions firmly expressed their preference for audiologists to provide this kind of support. They spoke highly of their GPs but acknowledged the time constraints and the need for GPs to focus on medical problem-solving rather than in-depth discussions about social-emotional well-being. Some of them also shared their experiences with psychologists who lacked understanding of hearing loss and hearing devices, offering simplistic solutions like wearing hearing aids to solve all problems. Many adults with hearing loss highlighted that psychologists often fail to grasp the difficulties they face in socializing due to hearing loss.

The spectrum of difficulties they face ranges from small day-to-day inconveniences to dire social and emotional impacts. While they may turn to psychologists in severe cases, they firmly believe that addressing the daily challenges caused by hearing loss should be the role of the audiologist. They emphasized that audiologists possess a deep understanding of the intricacies of hearing loss and its effects on communication, making them best equipped to provide the necessary support and guidance.

Based on the feedback and preferences expressed by our patients, it is evident that they highly value and desire the comprehensive support that audiologists can provide, encompassing the relational, social, emotional, and occupational aspects of their lives impacted by hearing loss.

8. Our patients want audiologists to provide social and emotional support. Do audiologists really want to venture into this space?

The majority do, yes. We conducted a national survey of audiologists in Australia about six years ago, and while the majority disclosed that they were not currently addressing their patients' social and emotional needs, a vast majority of them (98%) expressed a strong desire to improve their skills, knowledge, and capacity to support their patients in this way (Bennett et al., 2020). They agreed that it is something audiologists should be doing.

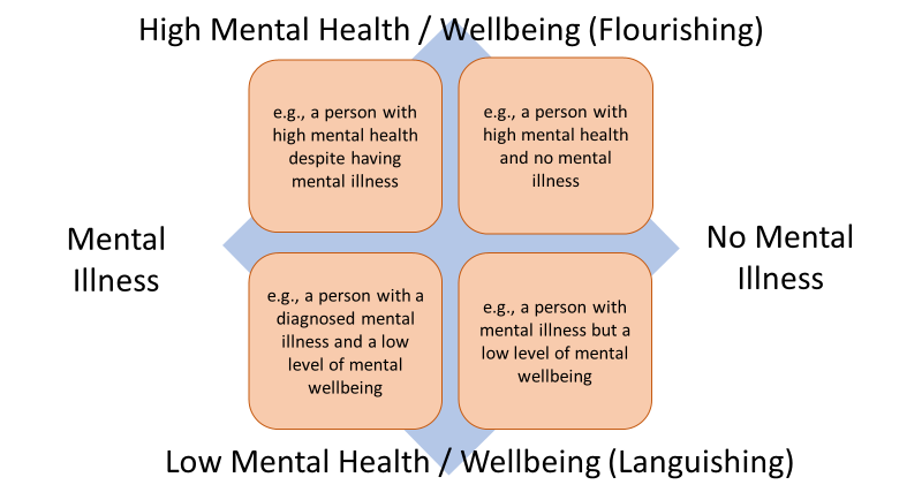

During the survey, many audiologists expressed concerns about defining the line in the sand. They questioned at what point providing social-emotional well-being support falls within our scope of practice and when it becomes outside of our scope. To address this question, I like to refer to a model from the psychology literature called the Two Continuum model (Westerhof & Keyes, 2010) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Two Continuum model.

Whereas we used to classify people as simply mentally ill or mentally stable, we now understand that psychological well-being and mental illness exist on two continuums. In this model, the x-axis represents the continuum of mental illness to the absence of mental illness, and on the y-axis, we have the continuum of psychological well-being. Focusing on the y-axis, at the top, we have people who are flourishing in their psychological well-being, such as when they experience general happiness, positive social connections, financial stability, and workplace effectiveness. At the bottom, we have people who are languishing, i.e., experiencing poorer psychological well-being, such as when people feel stressed, burnt out, anxious, burdened, or often sad.

Part of being human is to have fluctuations in our psychological well-being. We all fluctuate up and down the y-axis from week to week or day to day. Our goal as audiologists is to help individuals move up the y-axis, supporting their psychological well-being. For example, if someone is feeling anxious about certain listening environments due to their hearing loss, we can provide education, skills training, and support to empower them to communicate and socialize better in those situations.

However, it's important to note that we must not cross over into areas outside our expertise. We can and should focus on the impact of hearing loss and provide support related to hearing loss, but we should not diagnose or provide treatment for mental illnesses, such as generalized anxiety or depression. Instead, it is important that we refer to appropriate specialists, ideally those that we know understand the intimate relationship between hearing loss and psychosocial health.

As audiologists, we are expanding our role beyond solely addressing hearing deficits. We acknowledge the importance of supporting the psychosocial aspects of our patients' lives impacted by hearing loss while recognizing the need to stay within our professional boundaries.

9. What are some of the things that audiologists can do to help make a difference in their patient’s lives?

A couple of years ago, supported by a grant from Sonova, I led an international study with key researchers from Australia, UK, USA, Canada and the Netherlands, exploring how audiologists currently provide social and emotional well-being support to their patients. In total, 65 audiologists from different countries participated, and they identified 93 distinct approaches in their practices. They then grouped approaches, and seven conceptual themes were identified. Here are some of the specific ways audiologists can help their patients address their social and emotional well-being needs:

- Improving social engagement with technology: Audiologists can play a crucial role in helping patients improve their social participation by addressing their hearing deficits. While hearing devices are essential for improving hearing, it's important to highlight the significance of other devices and accessories that accompany hearing aids. Remote microphones like the Roger Pen or satellite mics, which are now available with many hearing aids, are remarkable devices that enhance communication in noisy environments such as cafes and restaurants. It would be beneficial to include these devices as standard during hearing aid dispensing to augment social functioning.

- Use of strategies and training to personalize the rehabilitation program: Audiologists can provide individualized training and education tailored to the specific needs of patients' rehabilitation. This includes communication training programs like the ACE program developed by Louise Hickson and Nerina Scarinci (spoiler alert: ACE 2.0 is currently under development – so watch this space!). These personalized strategies and training programs ensure that patients receive targeted support based on their unique requirements.

- Facilitating peer and other professional support: Audiologists can encourage patients to engage with their communities and connect with others who share similar experiences. This can involve attending support groups, both in-person and online, such as through social media platforms. Audiologists can also recommend other professional health services or offer specialized audiological services to cater to specific patient needs. Referring patients to hearing-specific support groups or organizations such as Lions Clubs, can provide valuable peer support for individuals with hearing loss and related conditions.

- Including communication partners: Audiologists can incorporate tasks that involve the active participation of patients' communication partners throughout the rehabilitation process. This includes educating communication partners, encouraging them to share their perspectives, and setting shared goals. Involving communication partners in the rehabilitation journey ensures that both individuals with hearing loss and their communication partners benefit from the program and experience improved outcomes. There is a ton of work coming out of the University of Queensland on how audiologists can include significant others (Ekberg et al., 2020) – well worth a read!

- Patient empowerment: Audiologists can assist patients in establishing rehabilitative goals based on their needs, wants, and barriers. This involves empowering them with knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy to manage their hearing loss effectively and make positive changes in their lives. Assertiveness training plays a significant role in this aspect, allowing patients to advocate for themselves and assert their needs in various situations. There is a growing body of work by Mel Ferguson and colleagues conceptualising empowerment along the hearing journey (Gotowiec, Larsson, et al., 2022), including development of a hearing specific measure of empowerment (Gotowiec, Bennett, et al., 2022).

- Providing emotional support: Audiologists can address the emotional needs of patients beyond the technological aspects. This includes creating a supportive environment where patients can express their feelings and thoughts related to their hearing loss. It involves utilizing counseling skills, such as actively listening, acknowledging their experiences, validating their emotions, and responding empathetically. Providing emotional support helps patients navigate the emotional challenges they may face during their hearing rehabilitation journey.

- Promoting patient responsibility: Shifting from a passive model of care, audiologists emphasize the importance of patients taking responsibility for their own rehabilitation journey. This includes promoting self-management of their hearing loss, encouraging self-advocacy (assertiveness) in social situations, and actively participating in their rehabilitation program. Patients need to recognize their role in creating a conducive social environment and actively engage in their hearing rehabilitation process, including the use of hearing devices and the necessary acclimatization. The audiologist can highlight the pivotal role that a patient plays in their own rehabilitation journey.

10. Okay, so it sounds like there are a lot of things that audiologists could be doing. Do you have any thoughts regarding why we aren’t all providing this type of service already?

That's a great question. We have some data on this. We conducted focus groups with audiologists from across Australia asking why they do not routinely ask about and provide support for the mental wellbeing impacts of hearing loss. We identified quite a few barriers. First, many clinicians feel that they lack the knowledge and skills to provide social and emotional well-being support. Reading more on the approaches I just described (Bennett et al., 2021) is definitely a good first step, but audiologists could also look to the clinical recommendations on social-emotional wellbeing for adults with hearing loss that we published earlier this year (Timmer et al., 2023). This is a wonderful resource to help audiologists really think about how to incorporate social and emotional wellbeing support into their routine clinical practices.

11. What about the skills gap?

Yes, that's another barrier that was mentioned. Audiologists expressed concerns about not knowing how to respond empathetically and fearing that they might say the wrong thing. Here's a quick tip for that: It's important for audiologists to use the language the patient uses when discussing mental well-being.

One Golden Rule I follow, based on working with some wonderful psychologists, is to use the terms introduced by the patient. For example, if the patient mentions "my social anxiety," then we have permission to call it social anxiety. If the patient expresses “worries about saying the wrong thing”, then we must use this phrasing. For example, we can explore their concerns by asking what situations they are in when the “worries about saying the wrong thing” come up for them. By using the patient's language, we can have meaningful discussions about their psychosocial needs without overstepping boundaries.

A big part of addressing this issue is learning how to respond with empathy. Fortunately, there are some wonderful resources available, such as the Ida Institute, which provides valuable tools and materials for audiologists to develop their empathy skills and enhance their emotional intelligence in patient interactions.

Another barrier we identified related to audiologists' perceptions of their role and responsibilities. Some audiologists felt that discussing emotions with their patients was not part of their job or “not something they signed up for,” despite many recognizing the importance of providing this type of support. Another barrier was the fear of opening Pandora's box by asking open-ended questions like "How are you?" and not knowing how to proceed if the patient reported social-emotional difficulties. This once again highlights the significance of knowledge and skills in supporting patients' social and emotional well-being.

12. There are individual-level barriers. What about barriers at the clinic or organization level?

At the clinic level, audiologists and clinic managers have mentioned that there often isn't enough time within appointments to have these conversations and support their patients' well-being needs. However, evidence shows that when patients feel heard and empowered, they have a better relationship with their clinicians and are more likely to follow their advice.

Audiologists also described a lack of clinical resources, such as discussion prompts, shared decision-making tools, and information sheets focused on social-emotional well-being.

13. How do you suggest we manage the time factor? In my practice, extending the time for a patient visit just wouldn’t work. Do you suggest I schedule post-fitting visits for this type of counseling? Are patients willing to pay extra for this service?

Providing counseling and support doesn't have to significantly extend the duration of the appointment, but I guess it depends on the situation. Let’s look at a few scenarios.

- Developing the skills to respond with empathy within standard appointments can actually save time. A 2014 study by researchers at the University of Queensland analyzed video recordings of initial appointments with older adults with hearing loss. Patients' psychosocial concerns were often expressed in a negative emotional manner, and when these concerns were not addressed during the appointment, patients would persistently raise them in subsequent interactions, leading to longer appointment times. Research delivering empathy training to family doctors shows that it not only helps improve skills for identifying clients’ bids for connection and for responding empathetically, but it also leads to shorter appointment times. Therefore, utilizing counseling skills within your routine practice, such as responding empathetically, could potentially be a time saver.

- Understanding the client’s immediate needs can save “wasted” appointments. Think about those patients who come in for three appointments to gather the information about hearing aids before they make a decision. Are they indecisive? Or is there something going on in their private life distracting them from being able to take in new information and make an informed decision?

As an example, I recall an encounter with a patient who disclosed that her sister had died that morning. Acknowledging her emotional state, we rescheduled the session to provide her with the space she needed to process her grief. I was able to use the time to catch up on paperwork rather than “wasting” time overwhelming her with information that she was likely to forget given her emotional state. Recognizing and addressing her emotional needs during that first encounter created a bond between us, and she became one of our most loyal patients who trusted us with her hearing care and referred all of her friends and family.

Similarly, there may be cases where allocating additional time during the initial appointment can save time in the long run. I vividly remember an encounter with an elderly patient who had consistently declined a hearing aid trial for a decade, despite acknowledging his worsening hearing loss. Instead of focusing on the technical aspects of modern hearing aids, I delved into his hesitation, sat with him in the discomfort, and asked what hearing aids represented to him. He expressed, "I'm not old enough for hearing aids." We engaged in a discussion about aging, loss, and the challenges of accepting physical limitations as we grow older. We explored the concept of healthy aging and identified how his friends who avoided hearing aids appeared older and more cognitively impaired due to their hearing loss. Investing time in counseling potentially saved him further years of uncertainty and finally motivated him to try hearing aids.

- Sometimes supporting peoples’ emotional needs does cost time, but it’s the right thing to do. There is a growing momentum for health professionals across all disciplines to take a “No wrong door” approach to mental health support. This notion suggests that all health professionals should welcome patient disclosure relating to mental wellbeing, open their door to being the first point of contact into the health system, and then actively connect the patient with the appropriate mental wellbeing support they require. By proactively acknowledging and connecting patients to the appropriate support, we contribute to the overall well-being of our patients and the community at large.

- We can’t add years to their lives, but we can add lives to their years. There are instances where we should book additional appointments wherein we deliver service-based hearing support, such as communication training (think ACE) and social coaching (see Barb Timmer’s paper for more (Timmer et al., 2023)). These services are valuable and rewarding, and clients (in Australia at least) are willing to pay for these additional sessions.

- Satisfied clients lead to repeat business and word-of-mouth referrals. When discussing rehabilitation goals with clients, it is important to go beyond simply asking about situations where they want to hear better. Take the time to explore the social activities they may have withdrawn from and express a desire to re-engage in. By helping clients recognize how hearing loss has impacted their social lives and offering support through the use of hearing devices and social coaching, audiologists can significantly improve not only their clients' hearing abilities but also their overall quality of life. Let us strive to optimize the entire hearing experience for our clients. Clinics that adopt a holistic approach to clinical service delivery, encompassing not just the provision of hearing aids but also comprehensive counseling and support, receive glowing feedback and testimonials from their clients, underscoring the tangible benefits of such comprehensive care.

14. What about barriers at the government or societal level?

One major barrier is the funding model. In places like Australia, government funding for hearing services is mainly tied to hearing device provision rather than addressing broader well-being needs. We need to develop evidence to show that providing holistic rehabilitation for social-emotional well-being leads to improved outcomes and benefits for society as a whole. I believe that the investment will be worth it in the long run. A happier patient means that they will also be a more loyal patient. I hope to be able to show this in the future through my work with a health economist.

There's also a stigma around discussing mental well-being in an audiology context, although some audiologists mentioned that the taboo is easing, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic brought more attention to mental health issues.

15. It sounds like you’ve been doing a lot of work addressing these barriers. What’s next?

We have recently developed a program called the AIMER program, which stands for Asking, Informing, Managing, Encouraging, and Referring (Bennett et al., 2023). It's designed to help audiologists address social-emotional well-being needs in their practice. We have created training materials, workshops, videos, and clinical resources to support audiologists in incorporating these practices. The program also includes a behavior change framework to identify barriers and develop solutions. Overall, it aims to empower audiologists to provide comprehensive care for their patients' well-being.

16. Sounds great! Can you tell me more about what the AIMER entails?

The AIMER program consists of various components designed to support audiologists in addressing their patients' social and emotional well-being. To describe just a few:

- Training Videos: Audiologists can access self-directed training videos to enhance their knowledge and skills in this area.

- Interactive Workshops: In-person interactive workshops are conducted to facilitate skill development among clinicians.

- Storytelling Videos: Videos featuring adults with hearing loss sharing their experiences, needs, and their expectations from audiologists.

- Interviews: Interviews with family physicians (General Practitioners), describing their perspectives on how audiologists and physicians can work together to best meet the needs of their patients.

- Psychologist Videos: Videos from psychologists providing insights on detecting symptoms and referring patients to psychologists for further support. This includes information on available funding, referral processes, and finding the right psychologist.

- Suggested questions for inclusion on case history forms or case notes to prompt discussions on mental well-being. Discussion prompts help open conversations about mental health with patients.

- Rehabilitation Goal Template: A template that incorporates not only hearing goals but also broader rehabilitation goals, addressing how hearing loss impacts various aspects of patients' lives.

- Patient Information Sheets: Information sheets are available for audiologists to use during appointments and can be given to patients to take home for further reading or to share with loved ones. These sheets cover topics such as the impact of hearing loss on relationships and strategies for improving relationships.

- Referral Templates: Templates for structuring referrals to GPs or psychologists, including descriptions of social and emotional challenges patients may be experiencing.

- Activity Scheduling Worksheets: Help patients and audiologists work together to identify social functioning needs and brainstorm achievable ways to overcome challenges.

Overall, the AIMER program offers a comprehensive set of resources and tools to support audiologists in addressing the social and emotional well-being of their patients.

17. Are these resources available for download?

Absolutely! The research and development of the AIMER program were published earlier this year in the journal of Implementation Science Communication (Bennett RJ et al., 2023). You can freely download the paper, which includes a link to access and download the resources we have developed.

We encourage clinicians to adapt these resources to suit their clinical practice and work environment. Feel free to customize them according to your needs and integrate them into your clinical practice. It would be wonderful to see these resources being used worldwide. If you have any questions about how to use the resources or any feedback on how we can improve them, or even stories of how you have used them in your clinic, please don't hesitate to reach out to me at bec.bennett@curtin.edu.au. I would love to hear from you.

I would like to express my gratitude to the Raine Medical Research Foundation for funding this valuable work.

18. Is there any evidence to support the effectiveness of the AIMER program?

Yes. After developing the AIMER program, we conducted an implementation-effectiveness study with 50 audiologists from a hearing service provider in Australia (Bennett et al., 2023). The study aimed to measure the impact of the AIMER program on their clinical services. We specifically measured three behaviors: (i) the frequency of audiologists asking patients about their social and emotional well-being, (ii) the frequency of providing general information about the link between hearing loss and social-emotional well-being, and (iii) the frequency of offering personalized support to manage the impacts of hearing loss on social and emotional well-being.

We utilized various approaches to measure these behaviors before and after implementing the AIMER program. This included self-report surveys, where audiologists reported an increase in knowledge, skills, and confidence for the three target behaviors. Additionally, the audiologists kept clinical diaries for six months before and after the implementation.

Furthermore, we audited the case notes of every patient seen by the audiologists over a three-month period before and after the training. An algorithm was used to count the frequency of social and emotional terminology within the clinical case notes. The average frequency across participating audiologists showed a significant increase in the use of social and emotional terminology.

Similarly, we audited report templates to count the frequency of social and emotional terminology in the GP reports. There was a significant increase in the use of such terminology by audiologists in their GP reports. Additionally, we audited the patient rehabilitation goals documented within a three-month period before and after training. However, there was no significant increase in the frequency of documenting social and emotional terminology in the COSI goals.

19. Interesting. What was the feedback from the audiologists who participated in the implementation study?

We conducted exit interviews with a small subset of audiologists who participated in the implementation study. The feedback received was overwhelmingly positive. Audiologists appreciated the quality of training and the resources provided during the study. They felt a sense of ownership in implementing the resources within their organization. Initially, some audiologists were hesitant and felt awkward about having conversations related to mental health. However, through training and practice, they acknowledged developing the skills and feeling more confident in having these conversations in their clinical practice.

Audiologists particularly liked that the training videos were recorded, allowing them to revisit the videos at any time. Some audiologists expressed interest in another round of training to consolidate their learnings and gain additional tips and resources they might have missed during the initial training.

It's worth noting that while none of the audiologists used all the resources, this was not the intention from the beginning. However, it was encouraging to see that each audiologist used at least one resource, and some utilized a dozen or more. The valuable feedback from the audiologists involved in the study will be used to improve the next iteration of the AIMER program.

20. Next iteration?

Yes, AIMER-online is on the way. We are currently working on designing a research study to digitize the entire AIMER program. This would allow organizations from around the world to download the training resources, train themselves and their colleagues, and access all the materials. As part of the study, we will collaborate with different hearing clinics across the country to test and roll out AIMER-online, addressing any issues that may arise. While funding is needed, I'm actively applying for grants to make this happen. It might take a couple of years, but we're working towards making the full AIMER program available to an international audience.

References

Bennett, R., Bucks, R., Saulsman, L., Pachana, N., Eikelboom, R., & Meyer, C. (2023). Evaluation of the AIMER intervention and its implementation targeting the provision of mental wellbeing support within the audiology setting: a RE-AIM analysis. Ear and hearing, Under review - Submitted March 2023.

Bennett, R. J., Bucks, R. S., Saulsman, L., Pachana, N. A., Eikelboom, R. H., & Meyer, C. J. (2023). Use of the Behaviour Change Wheel to design an intervention to improve the provision of mental wellbeing support within the audiology setting. Implementation science communications, 4(1), 1-22. Use of the Behaviour Change Wheel to design an intervention to improve the provision of mental wellbeing support within the audiology setting | Implementation Science Communications | Full Text (biomedcentral.com)

Bennett, R. J., Barr, C., Montano, J., Eikelboom, R. H., Saunders, G. H., Pronk, M., . . . Heffernan, E. (2021). Identifying the approaches used by audiologists to address the psychosocial needs of their adult patients. International Journal of Audiology, 60(2), 104-114.

Bennett, R. J., Meyer, C. J., Ryan, B., Barr, C., Laird, E., & Eikelboom, R. H. (2020). Knowledge, beliefs, and practices of Australian audiologists in addressing the mental health needs of adults with hearing loss. American journal of audiology, 29(2), 129-142.

Bennett, R. J., Saulsman, L., Eikelboom, R. H., & Olaithe, M. (2022). Coping with the social challenges and emotional distress associated with hearing loss: a qualitative investigation using Leventhal’s self-regulation theory. International Journal of Audiology, 61(5), 353-364.

Ekberg, K., Timmer, B., Schuetz, S., & Hickson, L. (2020). Use of the Behaviour Change Wheel to design an intervention to improve the implementation of family-centred care in adult audiology services. International Journal of Audiology, 1-10.

Gotowiec, S., Bennett, R., Larsson, J., & Ferguson, M. (2022). Development of a self-report measure of empowerment along the hearing health journey: a content evaluation study. International Journal Audiology, Submitted March 2022.

Gotowiec, S., Larsson, J., Incerti, P., Young, T., Smeds, K., Wolters, F., . . . Ferguson, M. (2022). Understanding patient empowerment along the hearing health journey. International Journal of Audiology, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2021.1915509

Timmer, B. H., Bennett, R. J., Montano, J., Hickson, L., Weinstein, B., Wild, J., . . . Dyre, L. (2023). Social-emotional well-being and adult hearing loss: clinical recommendations. International Journal of Audiology, 1-12.

Westerhof, G. J., & Keyes, C. L. (2010). Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. Journal of adult development, 17(2), 110-119.

Citation

Bennett, B. (2023). 20Q: social and emotional impacts of hearing loss—empowering audiologists. AudiologyOnline, Article 28651. Available at www.audiologyonline.com