From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

This month we’re talking about simulations. Not the kind that you are used to seeing in your hearing aid fitting software, but the kind that are used for training in healthcare, including audiology. Think of these as techniques to replace actual experiences that you would have with a patient in the real world. For most of us, our first health-care-related experience with simulation-based training was our good friend Resusci Anne, also known as CPR Annie or Rescue Annie—created in the 1950s by a French toymaker—no doubt the most kissed face in the world.

In audiology, of course, we also have a manikin known as the KEMAR, birthed in 1972 at Knowles Laboratory in Chicago, who rarely is kissed. While the KEMAR sometimes has been used for simulation-based training (e.g., learning the fine points of probe-mic measures), that was not the intent of the designers. He/she (depending on the number of neck rings) was designed to obtain more realistic measures of hearing aid performance.

A distant cousin of the KEMAR, dubbed CARL, has emerged in recent years.Unlike the KEMAR, the CARL, at least in part, specifically was designed for training purposes, and currently is used in several university programs.

The use of a manikin, however, is just one of many techniques that can be applied in audiology simulated training. Today we have methods such as standardized patients (actors), task-trainers, computer-based simulations, and virtual reality applications. We even have the product “artificial cerumen,” for those who want to hone their cerumen removal techniques on an artificial ear. To tell us about this exciting area of audiology training, we have brought in two experts for this month’s 20Q.

Katie Ondo, MA, is a Certified Healthcare Simulation Educator who specializes in medical simulation and the use of simulation for student and family training. She is the Editor in Chief for Simucase (a LaCalle Group company, along with continued.com and AudiologyOnline) and has been creating computer-based simulations for Simucase since the program's launch. She is a pediatric speech-language pathologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, where she specializes in acute care. Alicia Spoor, AuD, is President of Designer Audiology, Highland, MD. She is the current Legislative Chair for the Maryland Academy of Audiology and a Past-President of the Academy of Doctors of Audiology.

In their 20Q article, Katie and Alicia provide a comprehensive review of this emerging area of simulation training, how it can be implemented, and what we might see in the future.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Simulation-Based Training in Audiology

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Define simulations and explain how they address current challenges in clinical education within audiology and other health professions.

- Describe how simulations can be used in audiology education and training.

- List simulation options currently available to audiology programs, and discuss future directions of simulations.

1. What led to your interest in the use of simulations?

Katie Ondo: Early on in my career, I moved into an acute care setting as a speech-language pathologist. I saw firsthand how challenging it was to train, educate, and keep staff up to date with all education requirements. I became interested in the use of simulation-based education to assist with training staff and families. I am now the Editor in Chief of Simucase, which offers clinical simulations in many allied health professions. I oversee all simulation development to help train future clinicians.

Alicia Spoor: After completing some consulting work, I joined the Simucase team in Summer, 2020. Earlier in the year, I was fortunate to see the simulation work that was being completed in other professions (e.g. speech-language pathology, physical therapy) and wanted to help the Audiology simulation library grow consistently, as well. Additionally, as a former adjunct professor, I saw some of the accelerated and traditional residential audiology students struggling to integrate didactic education in front of a patient. Simulation allows the students to apply their classroom knowledge to patients in a forgiving environment. As one of my former professors would say, it’s a “win-win.”

CHSE is an international designation from the Society for Simulations in Healthcare (www.sshi.org). It means that I have passed the requirements as a Certified Healthcare Simulation Educator. The process included a review of my experiences and passing a certification exam. While there are over 1000 CHSEs around the world, there are only about a dozen SLPs and AuDs with the certification. I strongly encourage all audiologists who are involved in clinical training and meet the qualifications to obtain this credential.

3. Let’s start at the beginning. How do you define simulation?

A quick review of the literature will provide a number of definitions that are widely used. The definition that we use when we refer to clinical simulations is from a well-known researcher in the medical profession, David M. Gaba, MD, from Stanford University School of Medicine. Gaba (2004) defines healthcare simulation as “a technique—not a technology—to replace or amplify real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive manner”. This definition stands out among the rest as it puts the emphasis on the learning experience.

4. You used the term “healthcare simulation”. What do you mean by that term?

Simulations have an extensive history in military training. Aviation uses high-tech flight simulators to train pilots without risk to humans or the aircraft. Governments use simulations to train front-line responders in the event of emergencies. Businesses use simulations to teach employees leadership skills. In audiology and allied health professions, we focus on a different form of simulation - simulations used to train healthcare professionals to perform clinical skills, diagnose, treat, and participate in inter-collaborative teams. Healthcare simulations are a form of simulations that “creates a situation or environment to allow persons to experience a representation of a real healthcare event for the purpose of practice, learning, evaluation, testing, or to gain an understanding of systems or human actions” (Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 2017). Healthcare simulations are used by a variety of healthcare professions, including medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech-language pathology.

5. Is there evidence to support the use of healthcare simulations for clinical education?

Yes, there is a robust body of literature, using different simulation technologies, supporting the use of healthcare simulations for clinical education. From the nursing literature, we know that up to 50% of clinical education experiences can be replaced with simulation, and yield the same clinical outcomes (Hayden, Smiley, Alexander, Kardong-Edgren, & Jeffries, 2014). Researchers in physical therapy conducted a randomized control study (RCT) suggesting that 25% of clinical experiences could be replaced with simulations with no effect on student outcomes. Cook and colleagues (2011) performed a meta-analysis of more than 600 studies across multiple disciplines; the results strongly support the use of healthcare simulations as an effective teaching tool. Healthcare simulations have been shown to improve student performance and skills and positively impact confidence. Importantly, simulation training has also improved patient safety (Alinier, Hunt, & Gordon, 2004; Cook et al., 2011; Estis, Rudd, Pruitt, & Wright, 2015; Ward et al., 2015).

6. What has been done in audiology?

Computer simulations of hearing loss for teaching air conduction testing have been around for over 30 years. Tharpe and Rokuson (2010) reported simulated experiences with actors resulted in enhanced clinical experiences for students. More recently, Brown (2017) reviewed several different types of simulation training that are available today.

Ear Mold Impression (EMI) is an example used for teaching and assessing how students make EMIs. Cerumen management simulation training uses artificial cerumen for students to practice and become familiar with the different methods and removal tools used in cerumen removal without needing to be concerned with patient safety. Additionally, Brown provides an overview of OtoSim otoscopy trainer and AudSim Flex as well as practicing on a computerized manikin for Auditory Brainstem Response and Otoacoustic Emissions assessment. Brown concludes that students who use simulation will be more prepared for clinical situations, and the real-world experience will help develop and refine (rather than teach) skills. The didactic training, simulations, and clinical experience will produce better audiologists.

7. What are the different types of technology used in simulations?

The major types of simulation technologies include standardized patients, manikins, task-trainers, computer-based simulations, and virtual/augmented reality. Standardized patients refers to the use of a person or actor who simulates a patient in a realistic and repeatable way, such as we mentioned earlier regarding the work of Tharpe and colleagues. As the name implies, standardized patients are well-trained in carrying out scenarios in a standardized manner in order to elicit specific skills. Standardized patients are particularly effective in practicing communication and counseling skills.

8. Does our buddy KEMAR count as a simulation technology?

When people think about audiology manikins, they often do think about the Knowles Electronics Manikin for Acoustic Research, better known as the KEMAR. KEMAR, however, was designed for specific measurements of hearing aid performance, not for training simulations. The KEMAR does have a cousin, however, a manikin head, that was designed for training. He or she goes by the name CARL, which is an acronym for Canadian Audiology Simulator for Research and Learning, developed by Rob Koch, president of AHead Simulations (Scollie & Koch, 2019). The CARL is used in several Au.D. programs for clinical training in such areas as otoscopic examination, ear impressions, and probe-microphone measures.

In many other medical professions, manikins are high-tech, full-bodied representations. There have been rapid advances in this type of simulation technology. Digitized manikins used in medicine can have a heartbeat, breath sounds, and even sweat, bleed, and urinate. The manikins respond to the actions of the learner in a timely and predetermined manner. This type of technology is programmed and controlled by a skilled computer technician. You will find these technologies in simulation labs, which are most often associated with a nursing and/or medical school. They require considerable cost, space, and support.

9. You mentioned task-trainers. Can you tell me more?

Sure. Part-task trainers are used in healthcare simulations. Part-task trainers allow for practice of a particular skill and can be high- or low-tech. For example, Rescucci Annie is a part-task trainer used to train individuals in Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). CARL is a part-task trainer used to practice hearing aid measurements. A low tech task trainer would be the use of a silicon demonstration ear to practice earmold impressions.

10. I could see how computer-based simulations and virtual reality programs would be good teaching tools.

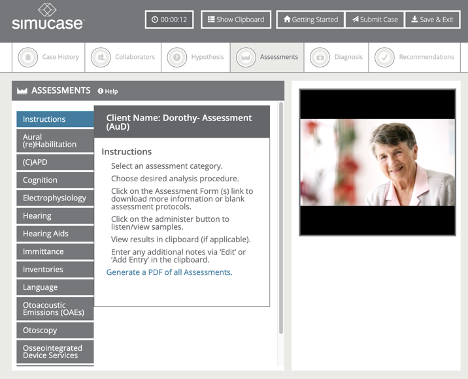

Yes. Computer-based simulations are developed and completed online through a computer or device, and can have a range of technical sophistication depending on the developer and software used. Simucase is an example of a computer-based simulation tool for the audiology profession. Within Simucase, users interview virtual patients to complete a case history, collaborate with other professionals, practice selecting assessments and interpreting results, and ultimately formulate diagnoses and recommendations. The system provides students with a competency based score that evaluates their clinical decision making abilities. Figure 1 shows a screen within a Simucase audiology simulation for assessment options.

Figure 1. A screen from the Assessments section of a Simucase audiology simulation.

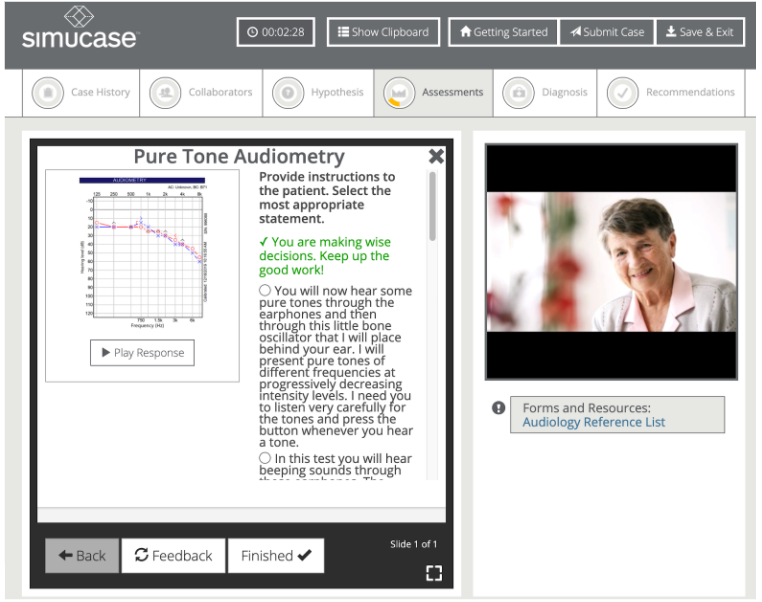

Students have an opportunity to review their competency scores based on the decisions they made and learn from their mistakes. Figure 2 shows a screen within a Simucase audiology simulation for administration and feedback within the platform.

Figure 2. A screen from a Simucase audiology simulation addressing the administration of pure tone audiometry.

One of the benefits of a computer-based simulation is that an entire class can evaluate the same patient. This can lead to comprehensive discussions as a class with clinical supervisors, preceptors, and didactic professors, alike.

Immersive virtual reality (VR) is likely the next technology to be applied to audiology simulations. Virtual reality is a three-dimensional representation of an environment that has the feeling of immersion. An example of VR for healthcare simulation would be interviewing an avatar in a clinical environment.

Many simulations use a combination of simulation technologies to provide a realistic simulated learning environment.

11. Can you give an example of how each of those types might be used in audiology clinical education?

Sure! A standardized patient (actor) can be used to simulate a counseling session in which the audiologist provides a family member with the results of audiologic testing. Manikins can be used to practice cerumen removal (using peanut butter, artificial cerumen) and high-tech manikins can be programmed to simulate a person in an in-patient hospital setting needing a bedside vestibular screening. Simulations are especially useful in training for grand rounds associated with interprofessional education. For example, a team of audiologists, otoneurologists, speech-language pathologists, and psychologists may participate in a simulation to determine if a patient is a cochlear implant candidate. Part-task trainers can be used on day one to provide practice in the use of an otoscope. Simucase is an example of a computer-based simulation specific to the area of audiologic diagnostics and intervention where individuals can complete a case history with a virtual patient, collaborate with professionals involved in the plan of care, determine assessments to administer, and interpret results to formulate a diagnostic statement and recommendations. Currently, we are unaware of any commercially available VR simulations in communication sciences and disorders (e.g. audiology and/or speech-language pathology). This could be an area of growth in the near future.

12. Where do you suggest we go to look up some of these terms?

As you see, the jargon in simulation cases is sometimes as difficult as the jargon used in other areas of audiology! This is also a relatively new area for many of us in audiology. The terminology can be confusing and may change depending on the discipline the individual practices. We can certainly suggest a couple of resources. One resource that is a great starting point is a series of articles published by The International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL). The articles include information about how to design, implement, and evaluate healthcare simulations. One of the articles in the series, The Simulation Glossary, is specific to the terms used in simulation. Another great reference that we often recommend is the Healthcare Simulation Dictionary, published by the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. We and our colleagues use both of these sources extensively.

13. What’s an OSCE? And how does that apply to simulations?

OSCE is an acronym that stands for “Objective Structured Clinical Evaluation.” OSCE’s are commonly employed in medicine, nursing, and healthcare professions to assess clinical competencies in undergraduate and graduate programs. Traditional OSCEs may include a series of practicum “stations” to assess a variety of clinical skills against a standard of performance. OSCEs are an area of great promise in our profession.

14. What do you attribute to the recent interest in audiology simulations?

Before March 2020, we would have stated a number of factors, including stressors in the audiology graduate programs, the limited number of quality, clinical rotation sites, and the limited time to rotate all students through each specialty.

15. And then COVID-19 came along.

Yes, the pandemic has brought simulations to the front of clinical education. In the current environment, graduate students may not have access to personal protective equipment (PPE), their off-campus internship rotations may have been canceled, and the number of patients coming in for face-to-face evaluations is also limited. Beyond COVID-19, simulations are specifically designed to allow all students to review, learn, and be assessed in a content area. One of the most positive areas we see with simulations is the ability for students to obtain clinical experiences and skills in areas that are not often available to them until a fourth-year externship, like cochlear implants and vestibular evaluations. We have seen a significant up-tick in the number of universities using simulations during the pandemic and it also affords undergraduate students the opportunity to see audiologists in a variety of settings, prior to “switching” from speech-language pathology to audiology. Simulation also follows medicine’s recent mandates for interprofessional education and practice.

16. How prevalent is the use of healthcare simulations in audiology?

Brown (2017) notes that audiology has been slow to embrace simulations. This may be due to a couple of reasons, including minimal attention given to the inclusion of manikins, standardized patients, and debriefing in educational programs, and limited resources available for simulations in programs. While adoption of simulation training has been slow in our field, it is gaining momentum. English and colleagues (2007) developed an instrument to evaluate audiologic counseling skills using standard patients and videotaped counseling sessions. While the focus was more on the tool, the article highlights the importance that students can both learn and be evaluated in a simulation environment. Additionally, audiology students report a positive experience when simulations were applied (Naeve-Velguth, Christensen, & Woods, 2013). Most recently, you may have read the AudiologyOnline interview with Jared Billey (2020). He recalls his experience at Western University using CARL, mentioned earlier. Billey elaborates how the manikin takes the place of another classmate or volunteer, allowing him to practice cerumen removal, earmold impressions, hearing aid fittings, and/or probe tube placements. One of the exciting things for us is the role Simucase can bring in simulations, providing another avenue to manikins and standardized patients. We have seen an increase in audiology programs using Simucase simulations since COVID-19 began in early 2020.

17. What are some of the reported benefits of simulations for clinical education?

The use of simulations follows the trend of medicine and we are happy audiology is following along. As noted earlier, the use of simulation allows graduate students to learn, practice, and refine skills in an artificial environment. Educators can use these simulations as class assignments, to test integration abilities from the didactic materials, and as part of the clinical training lab-work. Computer based and virtual reality (VR) simulations can also prepare the students by demonstrating correct and incorrect actions during a diagnostic or intervention case.

The role of simulations in audiology has been underutilized in the past. For audiology students wishing to pursue a CCC-A, the 2020 Standards from the ASHA Council for Clinical Certification in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology allow up to 10% of the hours required for a student’s supervised clinical experience to be obtained through simulations. The simulation can be synchronous (real time) or asynchronous (recorded). Supervision is still required by an ASHA-certified audiologist.

18. Where can we learn more about simulations?

Each year the Society for Simulation in Healthcare puts together a list of “Articles of Influence” which provides a compilation of highlights from four different simulation journals (https://www.ssih.org/SSH-Resources/Articles-of-Influence). That would be a good starting point. We also are aware that the major professional organizations such as ASHA, CAPCSD, and AAA are creating professional development opportunities for their members. Readers are also encouraged to look around for opportunities through our colleagues in speech-language pathology, nursing, and medicine. If an academic training program has a simulation lab on campus, start the conversations to collaborate.

19. What do you see as next steps for our profession in the area of simulations?

We see three major areas. The first is quality training in the pedagogy and technologies of simulation. The next area involves advancing research on the effectiveness of simulations in audiology. As is the case with all new paradigms, advocacy is the third area to focus on.

20. Any other thoughts to leave us with?

We encourage audiologists to read literature that is published in our professional journals on the use of healthcare simulations. Those audiologists in clinical educational settings can obtain simulation-specific information often from speech-language pathology colleagues, who have been routinely using simulations for years. Preceptors can also incorporate simulations to help students become more proficient in an area of audiology prior to seeing a patient in the clinic. The expanded use of VR also leaves a plethora of growth opportunities. We look forward to creating and providing additional audiology simulation experiences. We encourage readers to reach out to us with any questions or to discuss ideas for audiology simulations and content.

References

Ahmad, A. (2017). The use of simulation in audiology education to improve students’ professional competency. 10274142. [Published Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Arkansas for Medical Science.

Ahmad, A. A., Nicholson, N., Atcherson, S.R., Franklin, C., Nagaraj, N.K., Anders, M., Smith-Olinde, L. (2017). The Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 2(1), 12-28.

Alinier, G., Hunt, W. B., & Gordon, R. (2004). Determining the value of simulation in nurse education: Study design and initial results. Nurse Education in Practice, 4, 200–207.

ASHA. (2018) Certification Handbook of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association 2018 Audiology. Available at www.asha.org

Billey, J. (2020). Training & Product Learning with Simulation: A New Clinician’s View of the Benefits. AudiologyOnline, Interview #26857. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Brown, D.K. (2017) Simulation Before Clinical Practice: The Education Advantage. Audiology Today, 29(5), 16-24.

Cook, D. A., Hatala, R., Brydges, R., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hamstra, S. J. (2011). Technology-enhanced simulation for healthprofessions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(9), 978–988.

Dudding, C.C. & Nottingham, E. E. (2017) A national survey of simulation use in communication sciences and disorders university programs. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology. doi:10.1044/2017_AJSLP-17-0015

English, K., Naeve-Velguth, S., Rall, E., Uyehara-Isono, J., & Pittman, A. (2007). Development of an instrument to evaluate audiologic counseling skills. Journal of American Academy of Audiology, 18(8), 675-687.

Estis, J. M., Rudd, A. B., Pruitt, B., & Wright, T. (2015). Interprofessional simulation-based education enhances student knowledge of health professional roles and care of patients with tracheostomies and Passy-Muir® valves. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 5(6), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v5n6p123

Gaba, D. M. (2004). The future vision of simulation in healthcare. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 13(Suppl. 1), i2–i10. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i2

Hayden, J. K., Smiley, R. A., Alexander, M., Kardong-Edgren, S., & Jeffries, P. R. (2014). The NCSBSN national simulation study: A longitudinal, randomized, controlled study replacing clinical hours with simulation in prelicensure nursing education. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 5(2), S4–S41.

Naeve-Velguth, S., Christensen, S.A., & Woods, S. (2013). Simulated patients in audiology education: student report. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 24(8), 740-746. Society for Simulation in Healthcare, https://www.ssih.org/

Scollie, S. & Koch, R. (2019). Learning amplification with CARL: a new patient simulator. AudiologyOnline, Article 25840. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com

Ward, E. C., Hill, A. E., Nund, R. L., Rumbach, A. F.,Walker-Smith, K.,Wright, S. E., . . .Dodrill, P. (2015). Developing clinical skills in paediatric dysphagia management using human patient simulation (HPS). International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2015.1025846

Zraick, R. (2002). The use of standardized patients in speech language pathology. SIG 10 Perspectives on Issues in Higher Education, 5, 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1044/ihe5.1.14

Zraick, R., Allen, R., & Johnson, S. (2003). The use of standardized patients to teach and test interpersonal and communication skills with students in speech-language pathology. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 8, 237–248.

Zraick, R. I. (2012). A review of the use of standardized patients in speech pathology clinical education. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 19(2), 112–118.

Citation

Ondo, K., & Spoor, A.D.D. (2020). 20Q: Simulation-based training in audiology. AudiologyOnline, Article 27658. Available at www.audiologyonline.com