From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

When we think of balance disorders, we normally think of our adult patients. But, what is often overlooked is that many pediatric patients also have disorders leading to balance issues—perhaps to a greater degree than we recognize. Fortunately, there has been an increased awareness among audiologists of this potential pediatric disorder in recent years, and we’re going to advance that awareness here at 20Q this month by bringing in an expert on the topic.

Devin McCaslin, PhD, is associate professor at the Bill Wilkerson Center in the Vanderbilt School of Medicine and an associate director of the Division of Audiology. He also is co-director of the Division of Vestibular Sciences, maintains a clinical practice, and is an instructor in the Doctor of Audiology and Ph.D. programs. The Division of Vestibular Sciences also has a unique post-doctoral fellow program.

Dr. McCaslin has authored numerous publications that cover the areas of tinnitus, dizziness, auditory function, and outcome measures, and is the author of the clinical “go-to” vestibular handbook, Videonystagmography and Electronystagmography from Plural Publishing. He also serves as the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology and is President of the American Balance Society.

As Devin points out in this 20Q article, clinical audiologists need to be alert to recognize potential balance disorders in children, and in general be able to identify age appropriate motor milestones, know which disorders and syndromes are closely associated with dizziness, understand the tools and questionnaires that are available to screen children for vestibular impairments, and know where to send children for quantitative balance function testing and treatment. Reading Devin’s excellent article will put you well on your way to accomplishing these goals.

Gus Mueller, PhDContributing Editor

June 2016

To browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles, please visit www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Pediatric Vestibular Disorders and the Role of the Audiologist

Learning Objectives

- Participants will be able to name key vestibular reflexes and explain the role they play in normal development.

- Participants will be able to explain how audiologists can help to identify children at risk for vestibular impairments, and list associated common syndromes and diagnoses.

- Participants will be able to describe key considerations for the assessment of pediatric vestibular impairments such as case history questions, questionnaires, and appropriate objective testing that can be adapted or conducted for children.

- Participants will be able to discuss the types of follow up or referrals that may be indicated once a pediatric vestibular impairment has been identified.

Devin McCaslin

1. Pediatric assessment of dizziness? That’s something new for me.

It’s new for a lot of us, but truth be told, there has never been a more exciting time to be in this area of Audiology. New research in pediatric vestibular assessment and management has opened our eyes to the developmental consequences of balance impairments.

2. You say “developmental”—I remember something about the vestibular system having several end organs?

Right you are! In fact, there are five organs in the peripheral vestibular system with each one serving a different purpose. These five organs (three semicircular canals and two otolith organs) are connected to the two branches of the vestibular nerve (i.e. inferior and superior). All five end organs are functional at birth.

3. Is the entire vestibular system fully developed at birth?

The labyrinth is morphologically complete at birth and is the first sensory system to develop. The connections between the peripheral vestibular system and central systems required for balance continue to develop until the child is approximately 12 years old (Peterson, Christou, & Rosengren, 2006). It has been reported that vestibular responses peak at this age in order to facilitate the development of emerging motor skills and postural control. Following this critical period, the cerebellum begins to inhibit the vestibular system centrally.

4. I know in hearing that the central pathways travel through the brainstem and converge in the cortex. Is this also true for the vestibular system?

While both the auditory and vestibular systems share the same peripheral structure, they are quite different with regards to function and their distribution throughout the central nervous system. Vestibular afferents project to the cerebellum, autonomic nervous system, reticular formation, spinal cord, cortex and visual system. One of the key coordinating structures for balance are the vestibular nuclei (analogous to the cochlear nuclei). This group of cells receives information from the labyrinth, somatosensory system, and visual system and is a key element in the development of locomotion and postural control. The action of learning to walk is enormously complex and has several stages through life. The vestibular system, along with vision and proprioception, all factor into when a child learns to roll over, crawl, and then walk. Vestibular mediated reflexes are present at birth (e.g., head righting response). It stands to reason that children with impairments that alter the vestibular reflexes are slower than their normal counterparts in reaching key milestones.

5. Vestibular reflexes? Can you provide more detail?

One of the primary vestibular reflexes is the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR). When a child with a normal vestibular system moves his or her head, the eyes are reflexively deviated in the opposite direction so that the image is stabilized on the retina without blurring. This reflexive eye movement is called the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR).

6. Does an impaired vestibular system have an effect on a child’s vision?

Absolutely. The VOR is critical for children beginning to explore their environment. By 16 weeks of age, normally developing infants can move their heads back and forth in the horizontal plane. As infants learn to crawl and begin to reach for things that interest them, they must be able to see the objects clearly—even when the head is moving. Similarly, impairment in the peripheral vestibular system at birth can degrade a child's visual acuity during activity. However, children often do not complain of visual disturbance with head movement since they do not have a reference for what is abnormal. Adults with peripheral vestibular impairment often describe a blurring of the visual field during head movements and are known to restrict the speed at which they turn their heads. This decrease in visual acuity may be readily observed in children with vestibular impairments as well.

7. Okay, that makes sense. Are there any other vestibular reflexes?

Yes there are. In addition to the VOR, another key reflex is the vestibulo-spinal reflex (VSR). This one is critically important for the normal development of posture and gait. The VSR is a pathway by which information about head movement is relayed through the motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord to the myotatic reflexes. These deep tendon reflexes modulate the tone in the skeletal muscles of the trunk and extremities. The VSR relays information from the cerebellum, reticular system, and vestibular system to adjust posture and organize locomotion. In fact, if a vestibular system is completely impaired on one side, there is a corresponding reduction in muscle tone on the same side. There are some very good studies showing how the normal development of posture and locomotion can be disrupted in the presence vestibular hypofunction (Inoue et al., 2013).

Another reflex is the vestibulo-collic reflex (VCR). This reflex activates the musculature of the neck to stabilize the head. The upper limits for a normally developing child are head control at approximately 4 months and sitting unsupported at 9 months. The VCR is a key compensatory response to keeping the head centered over the body at this stage of development. Children with vestibular hypofunction have also been shown to have delays in controlling their heads (Inoue et al., 2013).

8. This all sounds quite serious. How many children have decreased vestibular function?

That’s a great question, and we don’t know the exact answer. The medical diagnosis of a child with a vestibular impairment is the responsibility of the physician (e.g., otolaryngologist, neurologist). Reaching this conclusion is less straightforward with children compared to adults for several reasons. Symptoms of dizziness will often manifest themselves differently in children than adults due to their limited verbal skills. Also, clinicians must often rely on the caregiver’s observations. There have been some comprehensive studies published recently, however, that attempt to address this very important question that you just asked. In one study by O’Reilly and colleagues (2010), it was reported that 1% of children ages 0-18 years presenting to a pediatric health system over a 4-year period had a primary complaint related to balance.

In a recent, first of its kind study, the prevalence of children with balance impairments and complaints of dizziness was estimated using the National Health Interview Survey Child Balance Supplement (Li, Hoffman, Ward, Cohen, & Rine, 2016). In this study, parents were queried whether their child was bothered by symptoms of dizziness and balance problems in the past year. Questions specifically targeted complaints such as light-headedness, clumsiness, poor coordination, poor balance, unsteadiness when standing-up or walking, frequent falls, or other dizziness and balance problems. Overall, 5.3% children (3.3 million US children) were identified as having dizziness and/or balance problems.

9. As an audiologist, what can I do to identify children with balance impairment?

I’d say in general, clinicians who test and treat children on a daily basis should be able to:

- Identify age appropriate motor milestones

- Know which disorders and syndromes are closely associated with dizziness

- Understand the tools and questionnaires that are available to screen children for vestibular impairments

- Know where to send children for quantitative balance function testing and treatment

10. Sounds reasonable. Let’s start with the first one. What should we know about motor milestones and vestibular impairments?

There is comprehensive data on how vestibular impairments affect adults both physiologically and psychologically. Only recently, have we really begun to understand how vestibular impairments manifest themselves in children. Audiologists and speech language pathologists working in pediatric settings are in a unique position to identify behaviors that are characteristic of impaired vestibular function. This includes observing activities such as playing, riding a scooter, climbing, or even simply reading. One of the key indicators of a vestibular impairment is whether a child achieves their traditional milestones at appropriate times. For example, normally developing children will begin to sit and crawl at approximately 5-6 months. That should be contrasted with the 8-18 months required to reach the same landmark for a child with a vestibular deficit (Kaga, 1999). It can take a child with a vestibular impairment 33 months to learn to walk independently versus only 12 months for an age-matched child with normal function.

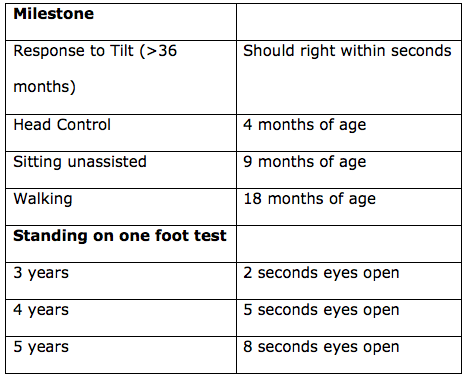

Emerging reports are converging on the fact that motor milestones are one of the first signs of a vestibular impairment in children (Rine & Wiener-Vacher, 2013). Furthermore, fine motor skills in children with vestibular loss have been shown to be delayed. These activities include passing an object from one hand to the other or building a tower with three cubes. Some pediatric audiology programs have instituted clinical protocols to monitor motor milestones closely in their patients with hearing loss in order to determine whether further investigation into the status of the child’s vestibular system is indicated. In this way, those children at risk can be identified and provided with timely intervention. Table 1 shows some benchmarks we use in our clinic to screen motor milestones.

Table 1. Benchmarks that can be used to screen motor milestones.

11. Are there any disorders that we should we being paying close attention to that may cause balance impairment in a child?

There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of disorders that can cause dizziness in children, but there are some usual suspects. Migraine is the most common cause of dizziness in the pediatric population, but not the most common cause of vestibular impairment. The age of onset can be as early as 2 years old. Another common cause of dizziness in children is otitis media. There is strong evidence to suggest that children with chronic otitis media, as well as those that have suffered a traumatic brain injury, have impaired balance and more accidents. It is now routine for the physicians and audiologists at our facility to ask about dizziness or unsteadiness in our pediatric patients with middle ear issues.

There are sources of dizziness that children and adults have in common. This includes vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis, and although rarely, even Meniere’s disease. Occasionally, you will see a child with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). The root cause of the BPPV is usually a head trauma or a recent surgery for cochlear implantation. Also, the presence of sensorineural (SNHL) hearing loss is often associated with vestibular deficits (McCaslin, Jacobson, & Gruenwald, 2011).

12. If hearing loss is a red flag for a vestibular impairment, it sounds like audiologists are in a good position to identify these issues.

Yes. It is becoming clear that vestibular impairment is an associated feature of SNHL. Children with hearing loss stemming from acquired and congenital etiologies should always be considered at risk for a vestibular impairment. In fact, there are reports that suggest that congenital disorders are one of, if not the primary, cause of vestibular deficits. There are numerous disorders that can result in congenital audiovestibular impairments. These include but are not limited to, Usher Syndrome, Pendred, Waardenburg, Albers-Schonberg, Albinism, Ushers, Wolfram, and Alport syndromes. The parents of children that present with these syndromes can be questioned regarding motor milestones, any reported dizziness, and whether they have any concerns about their child’s balance.

13. How do we know when a child’s dizziness warrants further evaluation?

Older children may be able to describe dizziness or imbalance, but younger children may be limited by vocabulary or developmental ability to express their symptoms. Instead, young children may exhibit acute signs of dizziness such as unexplained fright or unsteadiness. The first step in determining where to start with a child with dizziness or balance problems is the case history. In our clinic, questions regarding hearing risk factors such as medical, family and birth history are recorded. Additionally, when a provider evaluates a pediatric patient, the primary caregiver or child (if old enough) should be queried regarding whether there are any concerns with dizziness or balance. If the answer is yes, further questioning targeting the nature of problem should be undertaken. It is appropriate to start with questions regarding motor milestones (e.g., What age did your child learn to walk?). Questions regarding concerns with the child’s vision, coordination, and complaints of unsteadiness/vertigo should be asked.

14. What is the next step?

In our clinic we rely heavily on self-report measures to give us an initial gauge of what the impact of the dizziness is on an individual’s psychosocial function. In most adult clinics, it is common practice to administer handicap measures for dizziness, hearing, and tinnitus. Devices that ascertain the impact of dizziness on children are relatively rare. Recently, however, two questionnaires have emerged that can help providers to better understand to what degree a child’s quality of life is affected by their dizziness.

In an effort to develop an instrument to identify children with significant handicap/disability due to dizziness, our clinic developed an assessment tool for use in pediatrics. The Pediatric Dizziness Handicap Inventory for Patient Caregivers (pDHI-PC) is a self-report measure that is structured much like the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI; Jacobson & Newman, 1990). The device was designed to be administered to the caregiver of children 5-12 years of age (McCaslin, Jacobson, Lambert, English, & Kemph, 2015). It should be used to quantify the impact of dizziness on a child’s everyday life from the perspective of the caregiver. As with the adult version of the DHI, the pDHI-PC is comprised of questions that are written is such a way that they can be answered using the responses “yes”, “sometimes”, or “no”. The questions cover the physical, functional, and emotional aspects of a child’s life that can be affected by impaired balance. Interquartile scores have been calculated allowing the provider to quantify a child’s activity limitation as “none”, “mild”, “moderate”, or “severe”. The pDHI-PC can quickly and reliability provide clinicians with information regarding a child’s disability/ handicap imposed by their dizziness. Furthermore, it is useful in assessing the efficacy of therapeutic or medical intervention.

15. You mentioned two new questionnaires. What is the second one?

We don’t really know for a fact if there is a vestibular impairment until we do some quantitative testing and fortunately, a new questionnaire called the Pediatric Vestibular Symptom Questionnaire (PVSQ; Pavlou et al., 2016) can help point us in the right direction. The motivation was to create a questionnaire that would quantify the subjective vestibular symptoms that may be experienced by a child. The PVSQ was developed to identify and quantify subjective vestibular symptoms (dizziness and imbalance) in children between 6-17 years of age. A secondary study aim was to investigate the relationship between vestibular symptoms and behaviors indicative of psychological problems in healthy children and those with a vestibular disorder or concussions. The questionnaire was shown to be able to discriminate between children in a cohort of children presenting with vestibular symptoms and a normal control group.

16. Questionnaires are nice, but don’t you want some objective testing too?

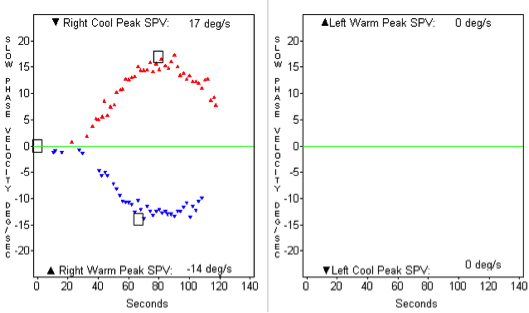

When appropriate, most certainly. There are a number of diagnostic tests that we as audiologists can do to determine if a child has a vestibular impairment. Two of the stalwart tests of vestibular function are videonystagmography (VNG) and rotational testing (Figure 1). In adults, these tests, in most instances, are very straightforward. Working with young children, however, is another matter and there are numerous adaptations to the testing that are being developed. For example, large screen televisions can now be used for ocular motor testing which allows for the use of cartoon characters as targets. The question of how information obtained from children differs from adults is currently being answered. One group that is making significant advances in understanding these differences is Dr. Steven Doettl’s laboratory at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Dr. Doettl is studying the errors and quality of data obtained during the ocular motor testing in children of different ages (Doettl, Plyler, McCaslin, & Schay, 2015). Currently, caloric testing, which evaluates the lateral semicircular canal, has proven to be a challenge with children younger than 5 years of developmental age. There are currently very little data describing the caloric response in young children.

Figure 1. A child set up for testing using an open rotational chair system.

A relatively new tool in vestibular assessment has been showing some promise for evaluating dizzy children is an adaptation of the bedside Head Impulse Test (bHIT). The high-tech implementation of the bHIT is the video Head Impulse Test (vHIT). This system employs goggles, an accelerometer, and a high speed camera, allowing for evaluation all six semicircular canals. There are some challenges with performing the vHIT on young children (i.e., 5 years old or less). Most notably, it has been observed that there is more artifact in young children, the goggles do not always fit snugly on a small head, and the child must maintain gaze on the target at all times.

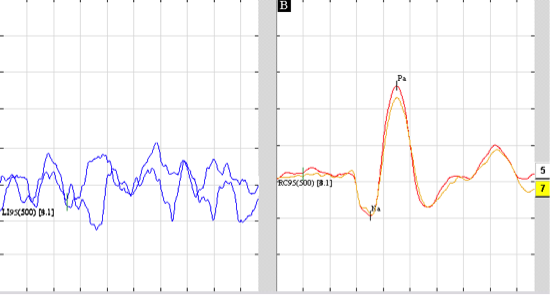

17. What about the VEMP test? Is this a test that can be done with children?

Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP) responses (i.e. ocular and cervical) have been shown to be useful for testing children. The tests can be completed relatively quickly, and have been shown to have excellent clinical utility for assessing the status of the otoliths (Kelsch, Schaefer, & Esquivel, 2006). First, the cervical VEMP (cVEMP) is a response that assesses the sacculo-collic reflex, which we talked about earlier. This myogenic response is recorded from an activated sternocleidomastoid muscle and represents a reflexive adjustment of the musculature in the neck triggered by activation of the saccule. The pediatric population shows decreased latencies and increased amplitudes compared to their adult counterparts (McCaslin, Jacobson, Hatton, Fowler, & DeLong, 2013)

The ocular VEMP (oVEMP) is characterized by an initial negative peak at ~11 msec that is followed immediately by a positive peak occurring at approximately ~15 msec. The negative polarity of the initial deflection suggests that the oVEMP is an onset response and is most robust from the contralateral eye. An ipsilateral response also can be recorded, however, it is inconsistently present. Normative data from the pediatric population shows equivalent latencies and amplitudes compared to their adult counterparts (Lavender and Bachmann, personal communication).

18. Is there a way to objectively measure the effect of a vestibular system impairment on the child’s overall balance?

There are a number of quantitative tests and screening procedures that can get at this question. For example, if a provider is interested in grossly screening the balance of a child 36 weeks old and older, there is normative data for standing on one foot with eyes closed. The modified Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction and Balance (mCTSIB; Shumway-Cook & Horak, 1986) can also be employed. This is a test where a child stands both on a hard surface and then on foam with eyes open and closed. There is published normative data for this evaluation. There are also more extensive examinations of postural stability that can be used with children as well. One is the NeuroCom platform posturography system (Figure 2). The NeuroCom platform has several tests that can evaluate the child’s reliance on vision, vestibular and somoatosensory information. Furthermore, this system has additional tests such as motor control and adaptation that can further evaluate a child's postural response to unexpected movements.

Figure 2. A child prepared for a postural stability assessment.

19. What can be done once a vestibular impairment is identified?

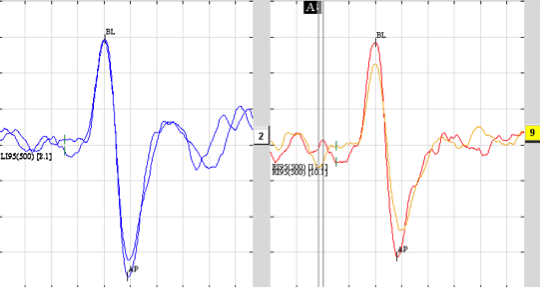

The clinician that is seeing dizzy children needs to be connected to medical and rehabilitative professionals that have an understanding of pediatric balance disorders. Following the identification of a child with significant balance impairment, a referral to a physician that is knowledgeable about dizziness is indicated. The type of physician may vary depending on the complaints and findings on a thorough screening. For example, if enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA) is suspected, a referral to otolaryngology may be advised. If screening and case history point toward a neuritis, then a visit to otolaryngology may be indicated. Test results from such a case are shown in Figure 3. Once it is determined through quantitative vestibular testing that a child has a peripheral impairment, vestibular rehabilitative therapy (VRT) may be an option. This is therapy performed by a specially trained physical or occupational therapist. Vestibular rehabilitation is successful in improving postural control, gross motor skills, dynamic visual acuity, and even reading acuity in pediatric patients with vestibular deficits (Rine et al., 2004).

Figure 3. A case of a 9-year-old child with a history of vertigo and suspected left-sided superior vestibular nerve neuritis. Top: A 100% left-sided caloric weakness; Middle: An oVEMP recording with an absent response from the left ear; Bottom: A normal cVEMP response bilaterally.

20. This seems to be a rapidly changing area of our scope of practice. Any final advice for audiologists?

Audiologists seeing children should make sure they are informed regarding the appropriate gross motor milestones for various age groups, as well as the signs and symptoms of vestibular impairment. Audiologists who provide routine hearing healthcare to children are in a unique position to identify children who may be at risk. Much has changed over the last few years with regards to awareness of balance impairment in children. In fact, several pediatric audiology programs now have dedicated care pathways to determine whether further investigation into the status of the child's vestibular system is indicated. As a profession, we need to remain vigilant for signs of this disorder in our pediatric patients, considering the fact that many are at higher risk for vestibular impairments than individuals in the general population.

References

Doettl, S.M., Plyler, P.N., McCaslin, D.L., & Schay, N.L. (2015). Pediatric oculomotor findings during monocular videonystagmography: A developmental study. J Am Acad Audiol, 26(8), 703-15. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.14089.

Jacobson, G.P., & Newman, C.W. (1990). The development of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 116(4), 424-7.

Kaga, K. (1999). Vestibular compensation in infants and children with congenital and acquired vestibular loss in both ears. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 49(3), 215-24.

Kelsch, T.A., Schaefer, L.A., & Esquivel, C.R. (2006). Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in young children: test parameters and normative data. Laryngoscope, 116(6), 895-900.

Li, C.M., Hoffman, H.J., Ward, B.K., Cohen, H.S., & Rine, R.M. (2016). Epidemiology of dizziness and balance problems in children in the United States: A population-based study. J Pediatr, 171, 240-247.

McCaslin, D.L., Jacobson, G.P., Lambert, W., English, L.N., & Kemph, A.J. (2015). The development of the Vanderbilt Pediatric Dizziness Handicap Inventory for Patient Caregivers (DHI-PC). International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 79, 1662–1666.

McCaslin, D.L., Jacobson, G.P., & Gruenwald, J.M. (2011). The predominant forms of vertigo in children and their associated findings on balance function testing. Otolaryngol Clin North Am, 44(2), 291-307.

McCaslin, D.L., Jacobson, G.P., Hatton, K., Fowler, A.P., & DeLong, A.P. (2013). The effects of amplitude normalization and EMG targets on cVEMP interaural amplitude asymmetry. Ear Hear, 34(4), 482-90.

O’Reilly, R.C., Morlet, T., Nicholas, B.D., Josephson, G., Horlbeck, D., Lundy, L., & Mercado, A. (2010). Prevalence of vestibular and balance disorders in children. Otology & Neurotology, 31(9), 1441-1444.

Pavlou, M., Whitney, S., Alkathiry, A.A., Huett, M., Luxon, L.M., Raglan, E.,...Eva-Bamiou, D. (2016). The Pediatric Vestibular Symptom Questionnaire: A validation study. J Pediatr, 168, 171-7.

Peterson, M.L., Christou, E., & Rosengren, K.S. (2006). Children achieve adult-like sensory integration during stance at 12-years-old. Gait Posture, 23(4), 455-63.

Rine, R.M., & Wiener-Vacher, S. (2013). Evaluation and treatment of vestibular dysfunction in children. NeuroRehabilitation, 32, 507–518.

Rine, R.M., Braswell, J., Fisher, D., Joyce, K., Kalar, K., & Shaffer, M. (2004). Improvement of motor development and postural control following intervention in children with sensorineural hearing loss and vestibular impairment. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 68, 1141—1148.

Citation

McCaslin, D.L. (2016, June). 20Q: Pediatric vestibular disorders and the role of the audiologist. AudiologyOnline, Article 17145. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com