From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

Workplace stress: something we’ve been hearing a lot about in recent years. The causes of workplace stress are varied and numerous: working long hours and through breaks, pressure to do more work than possible in a short amount of time, limited control over how you do your work, lack of necessary resources, poor support from or conflict with supervisors and co-workers, and low levels of recognition and reward, just to name a few.

Things are even worse if your day starts with having to get a couple of kids up and going, driving them to school or daycare, and then commuting to work for an hour in heavy traffic. Of course, the long drive does provide the opportunity to think about that student loan debt hanging over your head.

But wait . . . haven’t I heard that audiology is a low-stress profession? Back in 2018, one survey had us listed as the third least stressful—only beat out by hairstylists and medical sonographers. Is this really true? We thought it best to bring in an expert for this month’s 20Q, to give us the straight scoop on workplace stress in our profession.

Diana C. Emanuel, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Speech-Language Pathology & Audiology at Towson University in Maryland. She has been working in academia for over 30 years, including serving as the founding director of the Doctor of Audiology (AuD) program at Towson. She has received the University System of Maryland Regents Faculty Award, USM’s highest honor for teaching. Her connection to workplace stress is her current research focus on the Lived Experience of the Audiologist project, which is a multi-year exploration of the rich perspectives of audiologists.

You might be familiar with Dr. Emanuel’s textbook, Hearing Science, which focuses on foundational skills in both math and physics—every audiologist’s favorite area! In addition to her textbook, she has published several book chapters and articles on a variety of topics over the years. Many of you know her best from her very popular open-access video training series on Pure Tone Hearing Screening in Schools.

Even if you’re reading this sitting in your home office, in your sweats, with your favorite beverage on your desk and your cat on your lap, you’ll still appreciate Diana’s review of the stressors that are impacting many of your audiology colleagues in their work, and how this can best be handled.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Occupational Stress and Audiologists

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- List the most common stressors facing audiologists in the workplace.

- Describe strategies audiologists can use to try and reduce stress in the workplace.

- List strategies to improve patient-related stressors.

1. I recall reading somewhere that audiology is one of the top-10 least stressful professions. Is that really true?

Well, it certainly seems true based on audiologists’ inclusion on several of these lists for the last several years; however, the actual answer is: “it’s complicated.”

2. “It’s complicated” is not particularly enlightening. Are you saying these ranking lists are wrong?

They are not wrong, per se, but they are limited in scope because the researchers who create these lists must select what they want to measure, how they will measure it, and how they will merge the findings into one ranked list. Therefore, these lists are influenced by researcher bias and quality of methodology – but this is true of ranked lists for everything from the “5 Best Under-Eye Creams” to “Top 20 Best Home Workout Equipment” to “Top Audiology Graduate Programs.” Because researchers cannot measure every aspect of topics they investigate, their choices influence the results. It is also important to realize there are about 16,000 audiologists in the US, with diverse professional lived experiences, so one ranking number cannot capture the stress level experienced by all audiologists, nor does it capture the dynamic nature of stress in the workplace on a day-to-day basis. These considerations do not mean ranked lists have no value, but they do mean readers should be critical consumers and consider carefully who created the list and how it was created.

3. Okay, so let’s be critical consumers. Do you know how the low-stress professions’ lists are created?

To some extent, yes. There are several of these lists but let’s consider a popular one, the Top-10 Least Stressful Jobs from 2019 by CareerCast.com (2019a). That list was based on 11 general workplace stress factors (CareerCast.com, 2019b): travel, growth potential, deadlines, working in the public eye, competitiveness, physical demands, environmental conditions, hazards encountered, own life at risk, life of another at risk, and meeting the public.

Overall, the researchers at CareerCast.com selected a pretty good general list of workplace stressors and, from a big-picture perspective, identification of audiology as a low-stress profession is logical. This is because audiologists are expected to have less workplace stress than, for example, loggers and roofers relative to “hazards encountered,” less stress than surgeons and paramedics relative to “life of another at risk,” and less stress than mining, quarrying, and oil/gas extraction workers relative to “environmental conditions.” Note that these are vastly different jobs relative to education requirements, level of student debt, salary, day-to-day responsibilities, and so forth; thus, if the researchers had used different criteria, or if they had narrowed their consideration to focus on health professions, the rankings would be quite different.

4. I understand this list might have some flaws, but I’m still curious, where does audiology rank?

By considering those specific stress factors, CareerCast.com determined audiology was ranked number four. Here are the top-10 least stressful from that 2019 list:

- Diagnostic Medical Sonographer,

- Compliance Officer,

- Hair Stylist,

- Audiologist,

- University Professor,

- Medical Records Technician,

- Jeweler,

- Operations Research Analyst,

- Pharmacy Technician, and

- Massage Therapist.

When I consider this list, I find myself twice: as an audiologist (#4) and as a university professor (#5); however, I do not feel this low-stress rating represents my reality and I have seen similar comments expressed by audiologists on social media when these rankings come out. These top 10 lists are often useful for marketing purposes (e.g., recruitment of students into audiology), but a much better understanding of the nature of stress facing audiologists in the work place can be gleaned from research that focuses specifically on audiologists.

5. Has there actually been research that focused specifically on audiologists?

There is a lot of information in the literature about stress and burnout in general but, until recently, there was little information available on stress in US audiologists because past US studies focused on other occupation-related characteristics such as job satisfaction and burnout. For example, two studies of job satisfaction reported US audiologists generally tended to be satisfied with their jobs (Martin et al., 1997; Saccone & Steiger, 2012) and two studies of burnout reported educational audiologists had relatively low burnout (Blood et al., 2007, 2008). These studies, however, were conducted over a decade ago and a lot has happened within the profession recently.

More recent research, from Sweden (Brännström et al., 2013) and India (Manchaiah et al., 2015), found the majority of audiologists reported unfavorable working conditions that put employees at risk for burnout, where effort did not correspond with reward. In addition, two recent studies, from Australia (Simpson et al., 2018) and Canada (Canadian and US audiologists; Ng et al., 2019), reported findings for some audiologists that we should be concerned about relative to moral climate in the workplace.

Moral climate in healthcare professions concerns the way values drive healthcare decision making, support ethical practice, and impact the work environment for practitioners (Rodney et al., 2006). Simpson et al. (2018) examined Australian audiologists’ perception of moral climate using the Ethics Environment Questionnaire (EEQ) and found mean scores suggest audiologists, overall, tended to work within positive ethical environments. However, they also found that audiologists working in a setting most often associated with hearing aid dispensing (i.e., adult rehabilitation) had far poorer results for ethical environment compared with audiologists in other work settings. Following the EEQ survey, Simpson et al. conducted interviews to more fully explore the moral climate aspect of the work environment and found, “the most significant theme reported by participants associated with poor moral climate was described as pressure to meet sales targets from employers” (p. 391). The qualitative (interview) study by Ng et al. (2019) examined audiologists’ perceptions of the relationship between the hearing aid industry and the profession of audiology. Their findings indicated participants clearly perceived the symbiotic nature of the relationship between industry and audiology, but that this relationship can result in ethical tension, which is the uncertainty experienced by audiologists during clinical decision making when there is ambiguity as to the course of action that is ethically or morally right (Ng et al., 2019). In response to ethical tension, audiologists respond with a variety of coping mechanisms such as changing jobs or denying that the ethical tension exists.

When these recent studies are considered, along with a study of audiologist workforce projections that found higher than expected attrition of audiologists at mid-career (Windmill & Freeman, 2013), there is ample evidence to suggest the profession should take a closer look at itself, with a focus on the lived experience, how audiologists envision the profession will evolve, and how we can make changes that will improve the lived experience of audiologists in the future. This thought process inspired my recent work on stress and burnout in US audiologists.

6. What does your recent work tell us about audiology-specific stressors in the US?

Two recent papers on stress have emerged from my Lived Experience of the Audiologist (LEA) project. In the first, I describe stress-related content extracted from interviews with 28 US audiologists (Emanuel, 2021a). The second paper, with Madison Zimmer and Nick Reed, is a survey study in which we focused on burnout, quality of life, and stress, with 149 US audiologists as participants (Zimmer et al., in press).

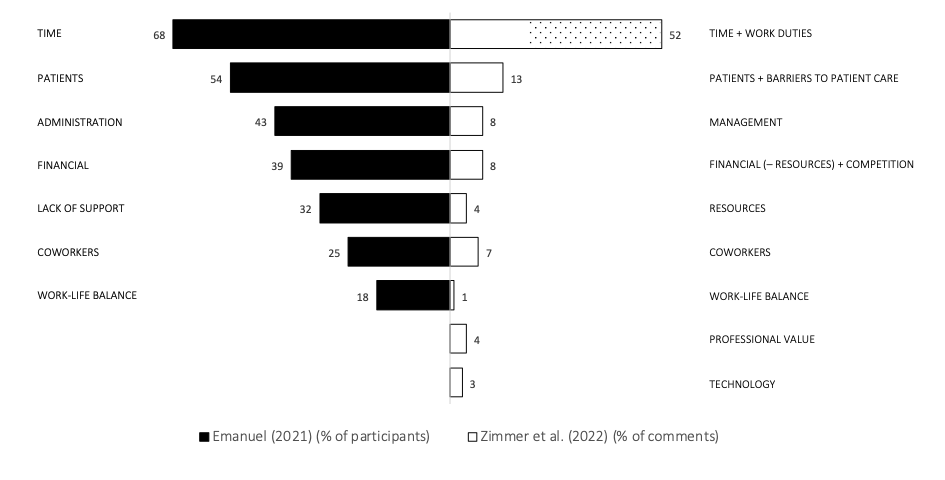

In the interview study, I asked audiologists to discuss aspects of workplace stress using prompts such as: “What are the primary drivers of your stress?” Participants could discuss as many stress factors as they desired. From the interview data, seven stress themes emerged (Figure 1). These seven themes, ranked in order from most to least relative to the percent of participants who described each theme in their commentary, are:

- Time (68% of participants)

- Patients (54%)

- Administration (43%)

- Financial (39%)

- Lack of support (32%)

- Colleagues (25%)

- Work-life balance (18%)

Juxtaposed to these data (see Figure 1, right side) are the results from the survey study led by Madison Zimmer (Zimmer et al., in press). In order to create an apples-to-apples thematic comparison for this figure, I had to re-consider a few themes and sub-themes. For example, Zimmer et al. reported “Barriers to Patient Care” as a unique theme separate from “Patients.” In my interview study, however, “Lack of Access to Care” was part of the “Patient” theme, so I merged these two themes for this comparison. The right axis label in Figure 1 clearly indicates the instances in which the Zimmer et al. thematic categories were shifted around so relative prevalence could be examined side-by-side. Notice that although the two studies included a different number of participants, used vastly different methodologies, and reported results in different ways, the relative prevalence of stressors was quite similar.

7. I’m looking at your chart, and I see that time and work duties from the survey study were merged. Why is this?

This is a great question and the answer has a lot to do with methodology. Let me provide some context. In the Zimmer et al. study, participants were asked to complete three surveys: the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) survey, and a survey about demographics and stress, which included a question that asked audiologists to list their top four stressors. This list was analyzed to create the stress themes. Consider how a typical participant would answer a question that asks for a list of stressors; most likely, the list would include single words or short phrases that provide relatively little context. Consider also that participants were asked to complete three surveys and, while I have found audiologists are often willing to donate their time to support AuD student research (Madison Zimmer was an AuD student when these survey data were collected), there is a limit to the amount of time audiologists have for this type of task, which is another reason I assume the list would include short phrases with little context. Example quotes provided the Zimmer et al. article illustrate the short response format; for example, “Chart notes/EMR,” and “Teaching AuD students".

Figure 1. Workplace stress themes for audiologists based on percent of participants from an interview study (Emanuel, 2021a) and percent of comments from a survey study (Zimmer et al., in press). Emanuel (2021a) data (left side) are listed in descending order based on percent of participants who contributed commentary within that theme. For comparison purposes, Zimmer et al. (in press) data (right side, data reported as percent of total comments) are listed next to the closest match with the Emanuel themes. Note the following changes in how Zimmer et al. data are reported here compared with the way data were reported in the original paper: (1) TIME + WORKDUTIES were reported as two separate themes in the original paper, but they are merged here for comparison purposes (highlighting indicates just the data from WORK DUTIES). (2) PATIENTS + BARRIERS TO CARE are merged here but were reported separately in the original paper. (3) RESOURCES is reported here as a theme, but it was a sub-theme in the original paper. (4) FINANCIAL – RESOURCES + COMPETITION merges all remaining data from the FINANCIAL theme with data from the COMPETITION theme from the original paper.

Contrast the survey methodology with the interview study methodology. For the interview study, I spoke one-on-one via virtual conferencing with audiologists who knew the interview would last about an hour. There was no pressure to “get to the end of the questions” because participants scheduled an hour to talk with me and did not know how many questions I would ask. My role as the interviewer was to encourage audiologists to talk and not to rush through the questions. As a result, rarely did I get a short answer in response to any of my questions. Thus, although the interview question, “What are the primary drivers of your stress?” could have resulted in a short-phrase list, it did not. Instead, participants were thoughtful and loquacious in their responses. They provided both stressors and extensive commentary with which I framed the stressors in a broader context.

So, getting back to your question, the context provided by interviewees was that time constraints were the driver of their stress and they framed work duties such as paperwork/administrative tasks as stressful because there was too little time during compensated work hours to complete all required work duties. Some audiologists described they were responsible for seeing back-to-back patients, sometimes with additional walk-ins, plus a high volume of paperwork, medical records charting, and other work-related tasks, and these tasks were so time-consuming that audiologists were often expected to bring paperwork home, work through lunch, stay late to see emergency add-on patients, and consult with patients from home after work. This is why I considered time and work duties together.

8. Does this mean all the work duties audiologists have to complete are stressful because we do not have enough time to do everything?

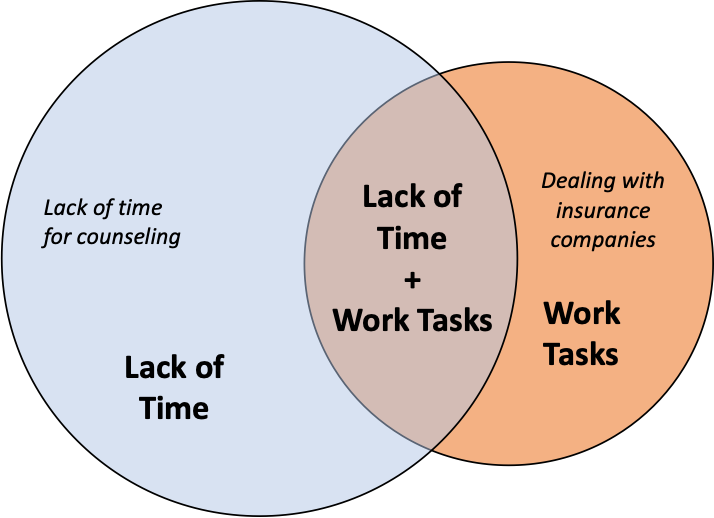

Despite what I learned in these two recent studies, and the context provided by the interviews, I think we need to do more research before we will have a clear picture of current stressors facing audiologists in the workplace. It is likely that the way I conceptualized time and work duties under one umbrella is an oversimplification and a better way to consider time and work duties may be to consider the model shown via the Ven diagram in Figure 2. Future research may reveal audiology tasks that are only stressful because there is insufficient time, tasks that are stressful because the tasks themselves are onerous, and tasks that are stressful because of a combination of time constraints and onerous tasks (i.e., stress could be reduced with more time but not eliminated). I suspect providing optimal, evidence-based, patient-centered care (e.g., more time for counseling, more time to conduct REM measures to confirm hearing aid fitting accuracy) will fall under the time category, and tasks such as dealing with insurance companies for reimbursement will fall under the task category. What I find exciting about this line of inquiry is that, if we identify which tasks are stressful regardless of time, this may help the profession makes decisions regarding division of labor in future audiology clinical service models. What tasks do we wish to retain as doctors of audiology and what tasks would we prefer to delegate in order to reduce workplace stress and/or improve clinic efficiency? Since the profession is evolving anyway, why not leverage research on lived experiences of current audiologists to shape the future of the profession?

Figure 2. Possible model explaining the underlying causes of work-duty and time-related stressors that impact audiologists.

9. Do you believe that research focused on understanding audiologists’ stressors is really important?

Most certainly. Audiologists have faced a lot of recent challenges pressuring us to shift away from the status quo, i.e., away from traditional ways of doing things that have worked well for many years, towards a future that involves change and uncertainty (Emanuel, 2021b). The challenges we face are diverse, from OTC hearing aids, to aggressive new competitors, to high levels of student debt facing recent AuD graduates, to the general devaluing of healthcare expertise in the current consumer-driven, pandemic-impacted economy. To put a label on audiology as a “low-stress” profession and call it a day ignores the reality of the lived experience of audiologists who are tasked with figuring out how to survive and thrive, personally and professionally, as audiology evolves. There will always be a certain amount of stress; in fact, a moderate amount of stress that has a positive impact on motivation and performance (called eustress) is considered an optimal state. However, chronic exposure to high levels of stress has long-term consequences on mental and physical health (Quick & Henderson, 2016). The short-term goal of the stress-related part of my research is to identify and understand the specific stressors faced by audiologists. The long-term goal of the Lived Experience of the Audiologist (LEA) project is to figure out what audiologists’ perceptions can tell us about how the profession is perceived, how we can reduce stress in the current profession, and how we can shape the future towards a profession that considers the lived experience as an important part of our evolution.

10. That all sounds good! Do you have any answers yet as to how can we change our professional lived experience to reduce stress?

At this point, I have a lot more observations than I have answers, but there are a lot of resources available – I will get to those later. Relative to my interview research, I often heard audiologists describe acceptance, and resentment, of the dual-level roles that some audiologists have. While all employees have myriad tasks at work, logic dictates a division of labor for efficient operations, with roles associated with credentials, expertise, salary, and so forth. What I found interesting was that many audiologists described serving as both a professional healthcare provider and as their own assistant and that many of the duties expected of audiologists were not expected of other doctoral-level healthcare providers. For example, audiologists reported they were expected to make their own copies of audiograms, sanitize their clinical areas, answer phones at the front desk, escort patients to the examination area, spend hours on the phone arguing with insurance companies, and so forth. When was the last time you saw a physician or dentist sanitizing exam rooms or spending 20 minutes on hold waiting to talk with an insurance representative? Other health care doctors appear to be better supported so they can focus more of their time on patient care. If we could find a way to re-allocate administrative time to patient care, I think this would have a positive outcome on workplace stress.

11. I agree, I experience exactly what you are describing. How do we change this?

There is evidence the profession is already finding ways to shift, but the pace feels slow. Hammill and Freeman (2001) conducted a survey two decades ago and found 24% of audiologists reported working with audiology assistants. More recently, a survey by Andrews and Hammill (2017), and a survey from my LEA project by Wince et al. (2022), both found 34% of audiologists reported working with audiology assistants. So, it looks like it took the profession about 20 years to increase the presence of audiology assistants from a quarter of audiology workplaces to a third. Maybe this will increase more quickly now that we have national audiology assistant standards, but that remains to be seen. Audiologists I interviewed cited lack of support (primarily lack of staff) as a prominent stressor and, unfortunately, some described situations in which they had hired an audiology assistant, but that position was the first to be eliminated when budgets got tight (e.g., during the COVID-19 pandemic), but service-extender personnel for other health specialties was retained. I see this as relating to lack of awareness of audiology and poor external valuation, which are two focus areas that have been on the agenda for national associations for years. Substantive changes in these two areas should help our ability to advocate for more support personnel.

12. How about our patients? What did you find regarding how they relate to our stress?

As I mentioned earlier when I discussed how I moved the Zimmer et al. categories around, “Patients” as a stressor includes two types of content: (1) stress caused by negative patient attitude/behavior, and (2) stress caused by audiologists’ inability to help patients. From my interview study, two-thirds of patient-related stress comments were negative attitude/behavior (e.g., lack of trust, resistance to care, rudeness) and one-third were focused on audiologists’ inability to help patients (e.g., patient lack of access to care, inability to improve patient quality of life). Findings from Zimmer et al. were similar, with about 75% of patient-related stressors focused on negative patient attitude/behavior and 25% on barriers to care. Fixing the access to care issue is tough in the US for political reasons. However, even if universal healthcare were implemented, we would likely face the same problem we have when patients have private insurance; specifically, for some reason, hearing care, vision care, mental health care, and dental care appear to be areas in which the human need for healthcare is treated separately from general healthcare and greater advocacy is required for insurance coverage. Here, again, this issue is on the national radar and the national professional associations are working on ways to improve patient access to care and reimbursement.

The larger part of the patient stress theme is associated with negative patient attitude/behavior. To chip away at this, looking at the big picture, patients and the general public are bombarded with direct-to-consumer advertisements, in which vendors deliberately obfuscate the role of the audiologist in hearing healthcare and encourage patients to purchase low-cost hearing aids, often without support services, and without sufficient patient education to understand the range of amplification options. Audiologists share in the responsibility for the obfuscation by bundling products and services, thereby inflating the perceived cost to consumers of hearing aids and hiding the cost/value of our services (Abrams, 2017; Fabry, 2019; Fifer, 2020). It is no wonder, then, that many of our patients are cautious and lack trust. One of our ongoing missions as a profession must be the education of patients (and others) to clarify the value of our services separate from the value of hearing aid products and to improve transparency of product and service pricing. In this regard, the profession has made some progress, with, for example, a decrease in the use of bundled pricing over time, from 84% to 52% of audiologists over the past 15 years (Wince et al., 2022). Will continued focus on transparent pricing and the value of our services improve workplace stress? That remains to be examined.

13. Are there any other strategies we can try now to improve patient-related stressors?

There is another avenue of exploration that may improve patient-related stress, based on considering how personality types impact communication between audiologists and patients. Carmen (2003) suggested awareness of personality type may provide insights into how audiologists interact with others and a few studies have explored how audiologist personality type can influence patient care (Traynor, 1997; Traynor & Holmes, 2002). Traynor and Holmes (2002) explain, “When the audiologist's type differs from that of the patient's, the clinician often tries to impose his or her style on the patient, resulting in poor interactions” (p. 30). Research in other professions has found connections between job strain and job satisfaction compared with personality traits such as neuroticism, extraversion, introversion, agreeableness, and so forth (Judge et al., 2002; Törnroos et al., 2013). Will audiologists’ self-awareness of personality type and focus on making active changes to communication improve audiologist-patient communication, and would this improvement reduce patient-related stress? Again, this remains to be seen, but it is possible.

One last thought on this topic is that there has been quite a lot of interest recently in the use of mindfulness meditation for various healthcare applications, including communication sciences and disorders. For example, a recent article by Sinnott and Mukherjee (2020) discusses how audiologists can focus on being present in the moment, which can improve patient-provider relationships and patient satisfaction, while simultaneously improving quality of life for audiologists at work and outside the clinic.

14. Let’s talk about the last of the top-three stressors: Administration. What is the nature of that type of stress?

In the interview study, “Administration” as a stressor was based on how audiologists were treated as employees. The majority of comments were associated with lack of autonomy, in which audiologists described how their ability to make clinical decisions was restricted as a result of administrative oversight. The rest of the comments were associated with inequity, in which audiologists described how administrators discriminated against audiologists compared with other health care professionals, in areas such as number of positions, compensation, and work hours.

15. How can the profession reduce the stress associated with administration?

Here again, one of our major challenges as a profession is the lack of awareness and valuation of the profession by others. During my interviews, some audiologists explained that they found advocating for support through multiple layers of administration when administrators did not understand our full scope of practice, was stressful. This goes back, again, to the need to educate others so they are aware of the value of audiologists in hearing healthcare. Audiologists know they have a high value, as do other health care providers and administrators who work closely with audiologists (Emanuel, 2021b). Some of my interviewees suggested audiologists, in general, do not do enough to advocate for themselves at the time of employment relative to the level of autonomy and administrative oversight. It is possible that administration-centered stress could be reduced if every administrator within a medical center had a clear understanding of our value within hearing healthcare.

16. What about research on this topic from audiologists outside the US?

Three international studies measured audiologists’ occupational stress using a survey called the Audiology Occupational Stress Questionnaire (AOSQ, Severn et al., 2012), which has yet to be used with US audiologists (I am working on that project now). These three studies were conducted in New Zealand (Severn et al., 2012), India (Ravi et al., 2015), and Sweden (Brännström et al., 2016). Some of the findings from the international studies were similar to findings from US audiologists. Lack of time is a global stressor. This theme is prominent in every study of stress, regardless of country. The “Administration” theme also emerged as a prominent stressor globally, although this was a single theme as described by Emanuel (2021a) and Zimmer et al. (in press) but it appeared as part of separate components within the international studies, such as “leadership at the workplace,” “job control,” “audiological management,” “accountability,” and “work targets.”

17. You talked about the similarities across studies, but what differences did you find?

There were two big differences I saw when comparing across studies. The first is that “Patients” was one of the most prevalent stressors for US audiologists, but this did not emerge as a prominent stressor in the international studies. Either it was not reported in the list of stress factors (Brännström et al., 2016) or it had a different nature, like “Patient contact and time” (Ravi et al., 2015). Severn et al. (2012) noted “patient unrealistic expectations” as the last item emerging from their qualitative data, but this is only a small part of the “Patients” theme that emerged from US audiologists. It seems from this comparison that the nature of healthcare in the US and/or the nature of US patients is fundamentally different compared with the international studies, which could have resulted in the differences in findings.

Another difference between studies is that both Severn et al. (2012) and Ravi et al. (2015) found stress varied significantly as a function of participant demographics (e.g., work setting, experience), which is consistent with earlier research on burnout for US audiologists (Blood et al., 2007, 2008). In contrast, neither Emanuel (2021) nor Zimmer et al. (in press) found significant relationships between stress ratings and demographics. I would have expected to see differences in stress across work settings, but the findings did not support one work setting being rated more or less stressful than another. With that said, there were some nuances within the qualitative data that indicated there were differences in the types of stressors described by audiologists in different settings work settings. For example, private practice owners were more likely to contribute content within the “Financial” stress theme (e.g., stress about competition, making payroll, paying bills) than to the “Administration” theme for the interview study. Curiously, in the Zimmer et al. study, the “Management” stressor was divided between content from employees complaining about administrators (70% of management comments) and content from business owners complaining about having to deal with employees as an administrator (30% of management comments).

18. Let’s go back to what you said in the beginning about workplace stress and individual responses to stress. Can you expand on that?

There is some emerging evidence indicating personality factors may influence the impact of workplace stressors. For example, during the interviews, when audiologists were talking with me about stressors, 25% of them introduced content related to their individual response to stress, which was not part of any of my question prompts. One audiologist stated, “I am an extremely laid-back person so I let a lot of things roll off my back...a younger woman that works with me...she struggles a lot with stress stuff” (Emanuel, 2021a, p. 1017). The frequency of this type of unsolicited commentary suggested it may be a fairly common perception. In essence, some of us react well to workplace stressors and some of us do not; thus, labeling the entire profession of audiology as low stress can be invalidating for audiologists whose lived experience is that of working in a highly stressful environment. If we are to meet the increasing market demand for audiologists, I think we need a better understanding of why so many audiologists leave the profession. Examining stressors may get us closer to understanding how the profession may improve retention.

19. What other findings from your studies do we need to know more about?

Here is something you might find interesting. During one part of the interview study, I asked audiologists to rate their stress on an average day and on their worst day. Significant differences between these two ratings indicated the perception of stress is dynamic depending on the nature of the day, which is not a surprising finding, but it suggests labeling an entire profession as low stress does not provide a clear picture of day-to-day changes in stress as more of a continuum than a point. When I compared stress ratings between average and worst days, the ratings were significantly correlated, meaning individuals who tended to rate average-day stress relatively low also tended to rate worst-day stress relatively low, and vice versa.

Zimmer et al. (in press) examined participant rating of the overall stress and, in another part of the survey, she asked participants if they were worried about OTC hearing aids. There was a significant difference in overall stress rating between audiologists who selected “yes” they were worried about OTCs compared to those who selected “no” they were not worried, with the “yes” responses associated with higher mean stress rating. This shows a connection between two different data points, one about overall stress and one about a specific point of worry.

20. What is the take-home message from your research?

Audiology is often listed as a low-stress profession, which is a great thing for recruitment but it is limited in usefulness as the profession addresses current challenges and evolves over time. There are myriad ways to address stress in the workplace at the national, work setting, or individual level that may help audiologists reduce occupational stress. Research on US audiologists is ongoing but indicates we share many common stressors, but we have a lot more to learn to shape our future with a focus on creating work environments with optimal stress levels.

While research is ongoing, several researchers and clinicians have created resources to help audiologists manage stress and burnout. Table 1 provides a list of quick reads to help audiologists get started.

Source | Title |

American Academy of Audiology (2020) | Managing stress and anxiety in an uncertain time. |

Glantz (2017) | ‘Least Stressful’ job in America? Demystifying workplace stress in audiology |

Kasper (2009) | Zen audiology: Cultivating mindfulness and the potential impact on your practice, profession, and personal life. |

Kreisman (2017) | Burnout in audiologists: Sources, susceptibility, and solutions. |

Nemes (2004) | Professional burnout: How to stop it from happening to you |

Sinnott & Mukherjee (2020) | Practice being present. Mindfulness |

Traynor (2016a) | Clinical Burnout in Audiology (Part 1) |

Traynor (2016b) | Clinical Burnout in Audiology (Part 2) |

Vaynshtok (2017) | Burnout busters we use in our practice |

Table 1. Resources for audiologists for managing stress and burnout.

References

Abrams, H. (2017). Audiologists respond to disruption with best practices. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA]. https://www.asha.org/Articles/Audiologists-Respond-to-Disruption-With-Best-Practices

American Academy of Audiology (2020, April 15). Managing stress and anxiety in an uncertain time. https:///www.audiology.org/managing-stress-and-anxiety-in-an-uncertain-time/

Andrews, J. & Hammill, T. (2017). Audiology assistant scope of practice and utilization. Audiology Today, 29, 48-55

Blood, I. M., Cohen, L., & Blood, G. W. (2007). Job burnout, geographic location, and social interaction among educational audiologists. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 105 (Suppl. 3), 1203–1208. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.105.4.1203-1208

Blood, I. M., Cohen, L., & Blood, G. W. (2008). Job burnout in educational audiologists: The value of work experience. Journal of Educational Audiology, 14, 7–13. https://www. edaud.org/journal/2007-2008/1-article-07-08.pdf

Brännström, K. J., Båsjö, S., Larsson J., et al. (2013). Psychosocial work environment among Swedish audiologists. International Journal of Audiology, 52(3), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027. 2012.743045

Brännström, K. J., Holm, L., Larsson, J., Lood, S., Notsten, M., & Turunen-Taheri, S. (2016). Occupational stress among Swedish audiologists in clinical practice: Reasons for being stressed. International Journal of Audiology, 55(8), 447–453. https://doi.org/10. 3109/14992027.2016.1172119

CareerCast.com. (2019a). 2019 least stressful jobs. https://www. careercast.com/jobs-rated/least-stressful-2019?page=3

CareerCast.com. (2019b). Jobs rated methodology. https://www. careercast.com/jobs-rated/jobs-rated-methodology-2019

Carmen, R. (2003, July/August). Personality types among audiologists as measured by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Audiology Today, 15, 14-19.

Emanuel, D. C. (2021a). Occupational stress in U.S. Audiologists. American Journal of Audiology, 30(4), 1010-1022. https://10.1044/2021_AJA-20-00211

Emanuel, D. C. (2021b). The lived experience of the audiologist: Connections between Past, Present, and Future. American Journal of Audiology, 30(4), 994-1009. https://10.1044/2021_AJA-20-00185

Fabry, D. (2019). What gets measured gets done: Calculating the value of professional service. Seminars in Hearing, 40, 214-219.

Fifer, R. C. (2020). Hearing aid reimbursement: A discussion of influencing factors. Seminars in Hearing, 41, 55-67.

Glantz G. (2017). ‘Least Stressful’ job in America? Demystifying workplace stress in audiology. Hearing Journal, 22–23, 26.

Hammill, T. & Freeman, B. (2001). Scope of practice for audiologists’ assistants: Survey results. Audiology Today, 13, 34-25

Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five‐factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 530– 541. https://doi.org/10.1037///0021-9010.87.3.530

Kasper, C. A. (2009). Zen audiology: Cultivating mindfulness and the potential impact on your practice, profession, and personal life. Audiology Today, 21(3), 52–55.

Kreisman, B. M. (2017). Burnout in audiologists: Sources, susceptibility, and solutions. Audiology Today, 29(2), 35–47.

Manchaiah, V., Easwar, V., Boothalingam, S., Chundu, S., & Krishna, R. (2015). Psychological work environment and professional satisfaction among Indian audiologists. International Journal of Speech & Language Pathology and Audiology, 3(1), 20–27.

Martin, F. N., Champlin, C. A., & Streetman, P. S. (1997). Audiologists’ professional satisfaction. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 8(1), 11–17.

Nemes, J. (2004). Professional burnout: How to stop it from happening to you. The Hearing Journal, 57(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10. 1097/01.HJ.0000292398.79310.26

Ng, S. L., Crukley, J., Kangasjarvi, E., Poost-Foroosh, L., Aiken, S., & Phelan, S. K. (2019). Clinician, student and faculty perspectives on the audiology-industry interface: Implications for ethics education. International Journal of Audiology, 58(9), 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2019.1602737

Quick, J. C., & Henderson, D. F. (2016). Occupational stress: Preventing suffering, enhancing wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(5), 459. https://doi:10.3390/ijerph13050459

Ravi, R., Gunjawate, D., & Ayas, M. (2015). Audiology occupational stress experienced by audiologists practicing in India. International Journal of Audiology, 54(2), 131–135. https://doi. org/10.3109/14992027.2014.975371

Rodney, P., Doane, G. H., Storch, J., & Varcoe, C. (2006). Towards a safer moral climate. Canadian Nurse, 102(8), 24-27

Saccone, P., & Steiger, J. (2012). Audiologists’ professional satisfaction. American Journal of Audiology, 21(2), 140–148. https:// doi.org/10.1044/1059-0889(2012/12-0005)

Severn, M. S., Searchfield, G. D., & Huggard, P. (2012). Occupational stress amongst audiologists: Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout. International Journal of Audiology, 51(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2011. 602366

Simpson, A., Phillips, K., Wong, D., Clarke, S., & Thornton, M. (2018). Factors influencing audiologists’ perception of moral climate in the workplace. International Journal of Audiology, 57(5), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2018.1426892

Sinnott, L., & Mukherjee, R. (2020). Mindfulness. Canadian Audiologist, 9(1). https://canadianaudiologist.ca/mindfulness-feature/

Törnroos, M. Hintsanen, M., Hintsa, T., Jokela, M., Pulkki-Råback, L., & Hutri-Kähönen, N., Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2013). Relationship between Five-Factor Model traits and perceived job strain: A population-based study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(4), 492-500. https://10.1037/a0033987

Traynor (2016a, November 9). Clinical burnout in audiology: Part I. Hearing Health & Technology Matters, Retrieved from https://hearinghealthmatters.org/hearinginternational/2016/clinical-burnout-audiology-part-1/

Traynor (2016b, November 14). Clinical burnout in audiology: Part II. Hearing Health & Technology Matters, Retrieved from https://hearinghealthmatters.org/hearinginternational/2016/clinical-burnout-audiology-part-ii/

Traynor, R. A. (1997). The missing link for success in hearing aid fittings. Hearing Journal, 50(9), 10–15.

Traynor, R. M., & Holmes, A. E. (2002). Personal style and hearing aid fitting. Trends in Amplification, 6(1), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/108471380200600102

Vaynshtok, J. (2017, July 24). 5 Burnout busters we use in our practice. ASHA Leader Live. https:///leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/5-burnout-busters-we-use-in-our-practice/full/

Wince, J., Emanuel, D. C., Hendy, N., & Reed, N. (2022). Change resistance and clinical practice strategies in audiology [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of Speech-Language Pathology & Audiology, Towson University.

Windmill, I. A., & Freeman, B. A. (2013). Demand for audiology services: 30-yr projections and impact on academic programs. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 24(5), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.24.5.7

Zimmer, M., Emanuel, D. C., & Reed, N. S. (in press). Burnout in U.S. Audiologists. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology.

Citation

Emanuel, D.C. (2022). 20Q: Occupational stress and audiologists. AudiologyOnline, Article 28159. Available at www.audiologyonline.com