From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

In recent years, there has been considerable discussion regarding information accessibility in hearing healthcare. That is when you provide information to a patient during or following a visit, how much of it is understood regarding the findings, diagnosis, and treatment plan? We know that much of this depends on the content, how the information is presented to the patient, and how much is remembered.

Regarding “remembering,” back in 2004, audiologist Bob Margolis wrote an eye-opening article for me when I was editor of the Hearing Journal Page Ten column. He summarized studies that found that only about 50% of the information provided by healthcare providers is retained; 40%–80% may be forgotten immediately. But it gets worse, Bob states that research also has found that of the information that patients do recall (~50%), they remember about half incorrectly. One study reported that patients could not recall 68% of the diagnoses told to them in a medical visit. When there were multiple diagnoses, they couldn't recall the most important diagnosis 54% of the time.

Part of remembering important information and compliance with recommendations lies with the clarity, and how it is presented. One area where this is especially critical is with newborn hearing screening brochures. Fortunately, we have a group of experts examining this, and one of them is with us this month here at 20Q.

Erin Picou, AuD, PhD, is Associate Professor, Hearing and Speech Science, Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. She is the Director of the Hearing and Affect Perception Interest Laboratory at Vanderbilt, and also teaches and mentors AuD and PhD students at Vandy. She currently is an Editor in the area of amplification for both the American Journal of Audiology and Ear and Hearing, and recently was named the outstanding reviewer for the International Journal of Audiology. Beginning on January 1st, 2023, she will be the Editor in Chief of the American Journal of Audiology.

Dr. Picou also serves on several committees related to best practices in hearing aid fitting, including the AAA’s guidelines for the audiologic management of adults with hearing loss, and the hearing aid standards committee of the Audiology Practice Standards Organization.

When patient information is provided, sometimes simple wording can be important, and make a difference. Erin gives us some thoughts in this area regarding newborn hearing screening brochures.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Newborn Hearing Screening Brochures - Changes are Needed

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of designing newborn hearing screening brochures to have accessible information.

- Summarize the accessibility of the current state-level newborn hearing screening brochures.

- Explain why the term ‘refer’ is not the best option for describing newborn hearing screening results.

1. I have never seen a newborn hearing screening brochure. Can you tell me a little about them?

Newborn hearing screening brochures are often given to families of newborns around the time of a newborn hearing screening. They are usually around 1-2 pages and contain pertinent information about the screening. Many state organizations have brochures, and some hospital systems use their own, so there is a lot of variability in what these brochures look like, what information is contained in them, and who writes them. Audiologists are often, but not always, involved in the design or redesign of brochures. Common topics in include a description of how newborn hearing is screened, the results of a screening, why hearing is important to development, what happens after a screening, a description of expected developmental milestones, and important next steps (e.g., continue to monitor milestones or schedule additional screening or diagnostic evaluation). The National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management maintains a list of state Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EDHI) websites and you can check out many current brochures here: https://infanthearing.org/statematerials/.

2. Thanks, that helps. Do you think they need to be changed?

I do, but before we get to the specifics, I want to say that this is related to the overall concern of healthcare information accessibility. That is, how easy it is for people to access or understand the information their healthcare providers share with them? The basic question is, can a patient who goes to their medical provider (surgeon, family doctor, audiologist, etc.) understand and remember important information about their diagnosis, procedure, or treatment? This is a broad topic that could focus on any number of aspects including the way the professional presents the information, the clarity of any written materials, or other factors that affect a patient’s understanding.

Recently there have been several publications related to information accessibility in hearing healthcare, a number of which suggest that our materials are written at levels above what would be accessible by many people (Caposecco, Hickson, & Meyer, 2014; Manchaiah, Kelly-Campbell, Bellon-Harn, & Beukes, 2020), and a couple which evaluate the benefits of modified information for hearing aid users (Caposecco, Hickson, Meyer, & Khan, 2016) and people with tinnitus (Ming & Kelly-Campbell, 2018).

3. Is this the work you are doing?

Yes, we are doing related work looking at healthcare information accessibility of specifically newborn hearing screening brochures. Importantly, I would like to mention that what we are talking about today was conceived by Drs. Anne Marie Tharpe and Sarah McAlexander. As you know, Dr. Tharpe is the chair of the Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and has worked tirelessly on behalf of infants and children. Dr. McAlexander was an AuD student in the department when she started this work; she is now working in Houston, Texas, still serving infants and other populations in a clinical role. We also had some outstanding clinicians on the project, Brittany Day (at Vanderbilt University Medical School), Alison Kemph Morrison (now at the University of Georgia), and Kari Jirik (current AuD student at Vanderbilt University Medical Center). I mention these people because they were instrumental in all phases of the project. I am merely the one who is talking with you today.

4. I understand. As they say, teamwork makes the dream work. Are you saying your team looked at newborn hearing screening brochures?

We did. We were interested in the accessibility of the information in the state-level brochures (including territories) that are currently being provided to families. We wanted to know if parents or guardians of newborns are being provided information that is easily accessible – that is, are the brochures clear and easy to follow. When I am talking about newborn hearing screening brochures, I mean the brochures that families are provided around the time of the hearing screening. Right now, all 50 states have EHDI programs in place for newborn hearing screening, and 43 states and territories have mandated newborn hearing screening programs. As a result, over 98% of newborns in the United States receive a hearing screening prior to one month of age (National Institutes of Health, 2018). In most states, families of newborns are provided a paper brochure similar to what I’ve described.

5. What do you think would happen if these brochures were not clear or were difficult to follow?

It seems reasonable to assume that if brochures are confusing, difficult to follow, misleading, or even not interesting, parents would simply discard them. Other than being environmentally unfriendly, simply tossing aside a newborn hearing screening brochure could have series consequences. For example, if a newborn fails a hearing screening, but the parents are under the impression that failures are common and nothing to worry about, they might not follow up with an audiologist to obtain the appropriate additional screening or diagnostic testing. In the United States, the lost-to-follow-up or lost-to-documentation rates are approximately 27% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021).

6. Are you saying that confusing brochures are contributing to poor follow-up rates?

I don’t know the answer to that question. It is easy to imagine a scenario where a newborn did not pass the screening, the parents did not recognize the importance of additional testing, they discarded the brochure because it was confusing or difficult to read, and then they never return for follow-up. In some of these cases, the baby will have undiagnosed hearing loss and will get a later start on important intervention services because they did not have the important follow-up testing. And, a poorly written brochure might not only impact babies who did not pass the screening, but also babies who did pass, as these brochures contain helpful information for all families.

The brochures, however, only are helpful if the information they contain is accessible. Directly linking the quality of the newborn hearing brochure to better outcomes, such as lower loss to follow-up rates or earlier identification of acquired hearing loss, would be very difficult because these outcomes are multi-faceted. That said, I suspect the quality and accessibility of the information contained in the brochure does affect outcomes, because we see that the accessibility of other brochures is directly linked to outcomes. For example, Caposecco et al. (2016) modified a hearing aid information brochure by lowering the readability grade level, making the text larger, using more graphics, and providing less technical information. They found that hearing aid handling skills of adults who were given the modified brochure were significantly better than those of adults who were provided with an unmodified, less accessible brochure.

7. Do the currently available newborn hearing screening brochures provide accessible information?

This was our primary question in a recent study that was published in the International Journal of Audiology, co-authored by the team I mentioned earlier (Picou et al., 2022). We gathered all of the brochures that were available on-line between June and October 2020. These are brochures developed and published by state-level organizations. We looked for the most recent versions available and found 59 brochures representing 46 unique states and territories (some brochures had versions for multiple screening outcomes). We downloaded all 59 brochures for evaluation.

8. How did you evaluate the brochures?

For each brochure, we looked several things, including readability, design, and use of pictures. For brochure readability, we used an on-line readability calculator to evaluate the ease of reading and approximate grade-level scores. The primary measure we used was the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG; McLaughlin, 1969), which provides an estimate of the number of years of education required for an individual to understand the text. For example, a score of ‘6’ would indicate the average 6th grader could easily understand the text.

We evaluated the brochure design using the Medication Information Design Assessment Scale (MIDAS; Krass, Svarstad, & Bultman, 2002), which includes 13 elements upon which to score a brochure (displayed in Table 1).

We also judged whether the pictures on the brochure were appropriate for the context. Specifically, pictures needed to be of newborns or screening equipment, and not of toddlers or hearing assistive devices (e.g., hearing aids or cochlear implants). The concern is that the latter pictures would confuse parents, sending the message that follow-up testing could wait until the baby was older or that not passing a hearing screening means the baby would need hearing aids.

9. What did you find?

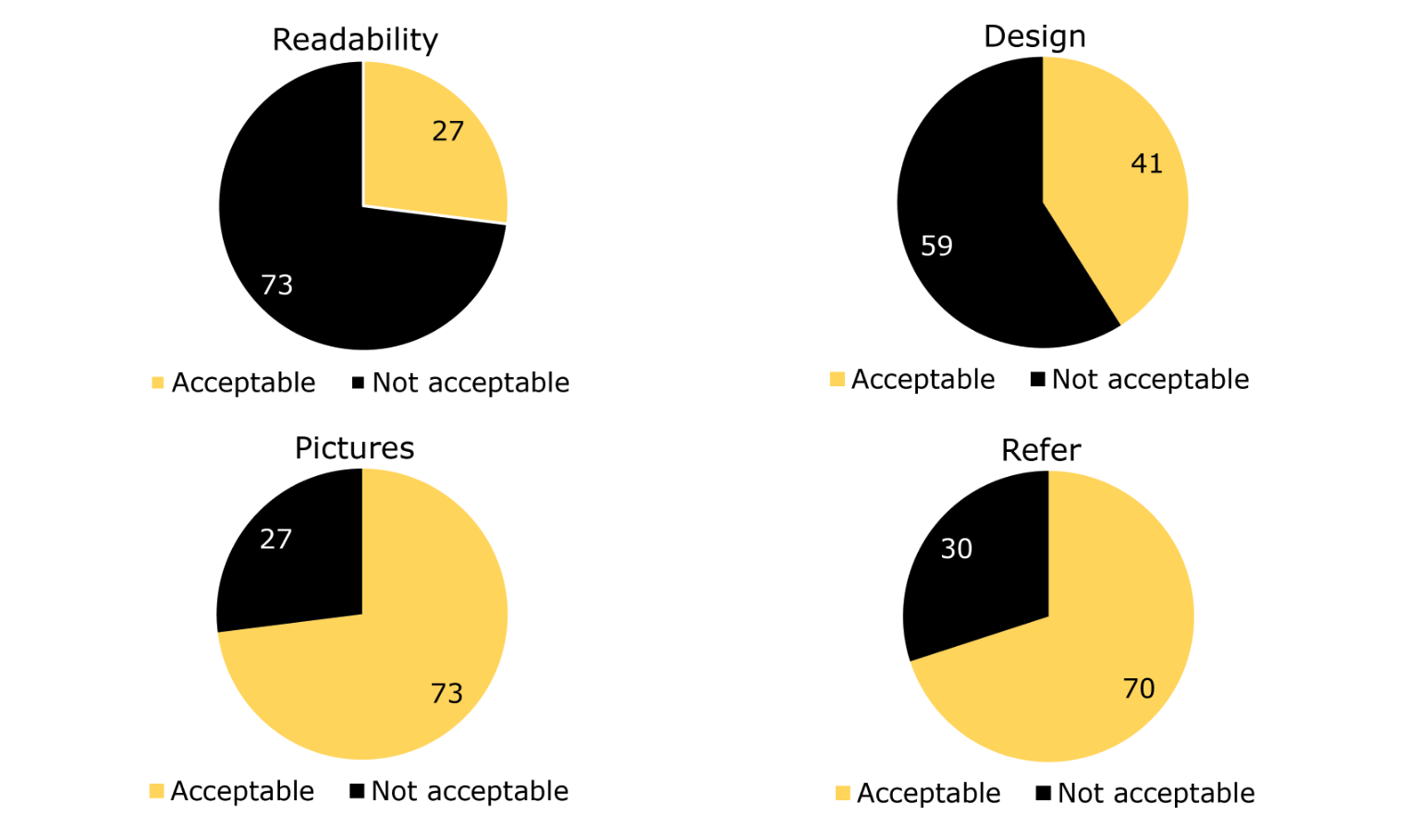

Figure 1 displays the key findings from these three evaluations. As you can see, most of the brochures (73%) were written above a 6th grade reading level. Given the average reading level in the United States is 7th- to 8th grade (Marchand, March 22, 2017), these findings indicate most of the newborn hearing brochures will not be broadly understood.

Figure 1. Percent of brochures that passed (or did not pass) each evaluation performed.

For the brochure design, we considered MIDAS score of 9 or higher was considered passable. There are 13 elements and achieving 9 of them would mean 69% of design elements evaluated were acceptable. Of the 59 brochures evaluated, none passed all 13 elements, indicating every available brochure could be improved on at least one MIDAS element (listed in Table 1). Only 28 (41%) met the threshold for an acceptable MIDAS score, revealing most of the brochures had designs that were not optimal for understanding. The elements failed most often included use of sans serif font, small margins, long line lengths, and no boxes for main points.

Although the readability and design outcomes seem generally unfavorable, most of the brochures had appropriate pictures. Only 27% of them included pictures with the potential to confuse patients and families. Most often, the inappropriate pictures were of older babies or young children, which might unintentionally send the message that follow-up is not urgent.

10. I notice in that figure there is also a panel related to refer. What does that mean?

We evaluated one additional aspect of the brochures, specifically, whether or not the brochure used the term ‘refer’ to indicate when the baby did not pass the hearing screening, rather than ‘did not pass’ or ‘fail.’

11. On the figure, I see 30% of brochures were rated as ‘acceptable’ on this evaluation. Does that mean they used the word refer to indicate a baby did not pass the hearing screening?

Actually, it’s the opposite. The 30% of brochures that we judged to be not acceptable on this evaluation used the word ‘refer’ to indicate the hearing screening result. We were concerned that using the word ‘refer’ to indicate that a baby did not pass a screening could be confusing. Therefore, we judged these brochures as ‘not acceptable’ on this evaluation if they used the term ‘refer.’

12. What’s wrong with the term refer? It sounds less harsh than ‘fail’ to me.

You are right. There have been advocates for this approach arguing that practitioners should not use the word “fail” because it could increase parental anxiety (e.g., Bess & Paradise, 1994; Hyde, 2005), whereas the use of the word ‘refer’ describes the immediate next step (i.e., the baby is referred for further testing; Hyde, 2005), potentially without negative connotations. The newborn period is a time of rapid change and a deluge of new information for families. Therefore, it is especially important to convey information clearly and accurately, while striking a balance with anxiety. On one hand, we don’t want to increase anxiety unnecessarily, but on the other hand, we need parents of babies who did not pass their screenings to take the result seriously and return for follow-up testing. And under all circumstances, we want parents and families to understand the next steps.

13. Do we know that the word refer is confusing?

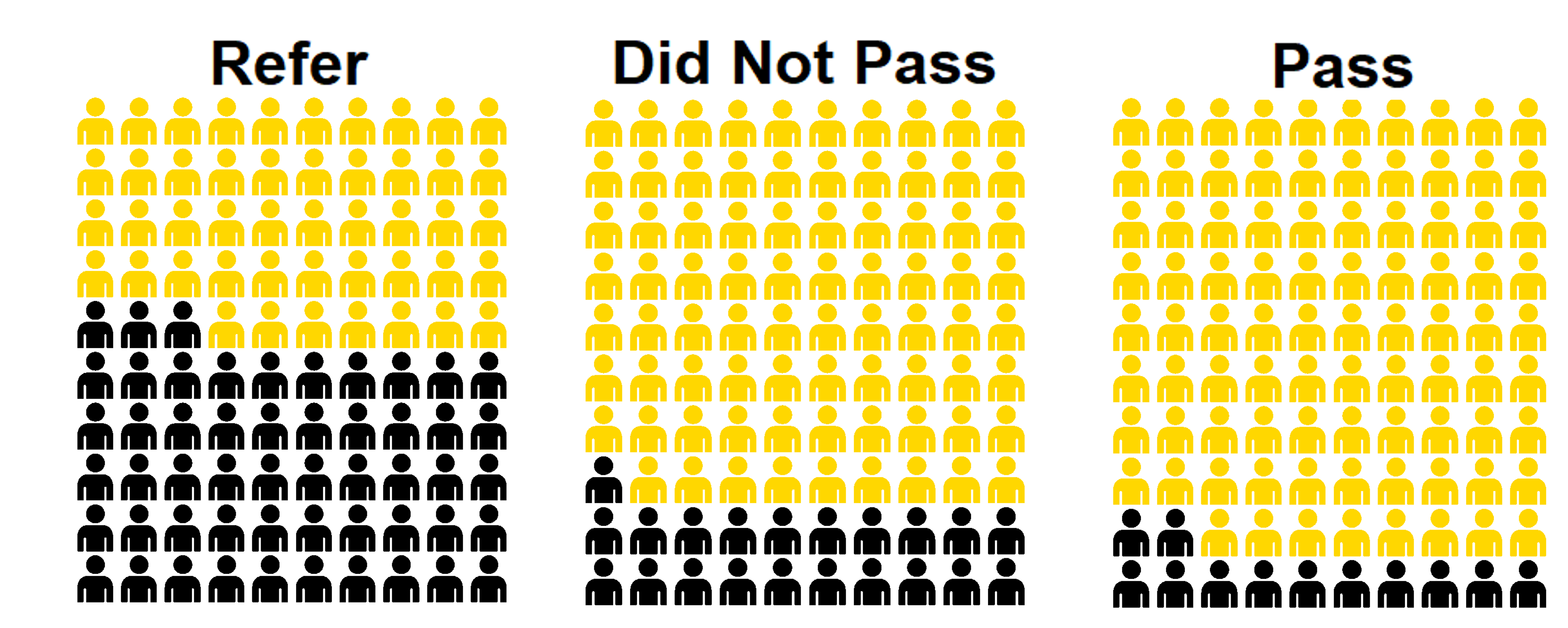

We do, as we looked at this question in our research. Dr. McAlexander asked 44 pregnant people (between November 2019 and February 2020), who were in a waiting room for prenatal appointments, if they knew what the word ‘refer’ meant in the context of a hearing screening, and asked them to define it using their own words, to ensure they did know the meaning. She also asked them if they knew what the terms ‘pass’ and ‘did not pass’ meant and asked for definitions as well. It turns out that most people (53%) did not know what ‘refer’ meant, whereas most people (88% and 79%) understood ‘pass’ and ‘did not pass,’ respectively (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Visual representation of the percent of participants who understood (gold symbols) or did not understand (black symbols) each term in the context of newborn hearing screenings.

Interestingly, we did some analyses to identify potential predictors of not understanding ‘refer’ and found that only age was related to understanding the term; younger people were less likely to understand it. Understanding the term ‘refer’ was not related to level of education or whether or not they were first-time parents. This is pretty compelling evidence that the term ‘refer’ has the potential to be confusing and we should not use it to convey newborn hearing screening results.

14. You’re saying that it’s okay to tell parents their baby ‘failed’ a hearing screening?

Not everyone will agree with us that we should avoid using ‘refer.’ However, the idea that ‘refer’ should be retired from our hearing-screening lexicon has some growing support. The most recent Joint Commission on Infant Hearing guidelines uses the term ‘fail’ instead of ‘refer’ explicitly because of the potential for the word ‘refer’ to be confusing (Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, 2019).

15. I notice that you used ‘did not pass’ rather than ‘fail’ as potential terminology in your study. Was that intentional?

We decided not to use ‘fail’ for the reasons we’ve just discussed – it has some negative connotations and might not be acceptable to the Deaf community, where members have raised concerns over words like “loss” and “impairment” (Shearer et al., 2019). Therefore, we chose to study ‘did not pass’ as an alternative to ‘refer,’ because it does not have the same connotations as ‘fail’ and was expected to be easily understood.

16. Did you find out anything else of interest about the different terms?

We did. In addition to understanding of result terminology, Dr. McAlexander also asked the pregnant people how anxious they would feel if they were told each of the terms were the results of their baby’s hearing screening. The median rating, on a scale of 1 (not at all worried) to 4 (very worried) was 1 for the ‘pass’ result, 3 for a ‘refer’ result, and 4 for a ‘did not pass’ result. This finding demonstrates that, as expected, pregnant people do not expect to feel anxious about a ‘pass’ result, but would be worried about a ‘refer’ result and were even more likely to be worried about a ‘did not pass’ result. Given that anxiety has been related to healthcare recommendation compliance (Mevorach, Cohen, & Apter, 2021), we interpret this pattern of results to demonstrate that ‘did not pass’ is a good alternative to ‘refer’ because it is understandable and is expected to cause parents to be anxious enough to follow-up with recommendations for additional testing.

17. Is the use of the term refer common in the brochures your group reviewed?

Of the brochures we examined, 30% use the term ‘refer’ to indicate a baby did not pass their hearing screening (see Figure 1). I don’t have data to prove that the term is associated with increased loss-to-follow-up rates, as I mentioned earlier, but I am convinced that the term has the potential to be confusing. We should be doing everything we can to increase the accessibility of the information we provide to patients and families, so replacing the word ‘refer’ with ‘did not pass’ is a good step. Plus, it is a low risk and hopefully an easy change that we can make. I am hoping that if you are involved with updating or revising your newborn hearing screening brochure for your local organization, and your current brochure uses the word ‘refer,’ that you will consider replacing ‘refer’ (or even ‘fail’) with ‘did not pass.’

18. Do we need to remove the word refer completely from our brochures?

I don’t think that’s necessary. Some brochures used the word ‘refer’ to indicate that a baby was being ‘referred’ for additional testing. I think we can reserve the term for exactly that context and still use the phrase ‘did not pass’ to indicate screening results, for example, by indicating that a referral to an additional screening or a diagnostic test is the next step. This strategy was evident in 17% of the brochures we evaluated. Approximately half, however, of all the brochures didn’t use the word ‘refer’ at all.

I do think it’s critical to note that, that even for the terms that are most likely to be understood (did not pass, pass), not everyone understands them within the context of newborn hearing screening results. This means our brochures and oral communication need to be very clear and we need to minimize the potential for confusion throughout the brochures, because even using the clearest term possible, some people might be confused (as depicted in Figure 2) without additional information.

19. Do you have recommendations for modifying the existing newborn hearing screening brochures to make them more accessible?

Of the brochures we examined, we judged only 12% to be acceptable on all of the evaluations (readability, design, appropriate pictures, and use of the term refer). This suggests that most of the currently available brochures could be revised to be more accessible for parents and families. Based on what we’ve seen, I recommend thinking about at least the following four things:

- Check brochure readability. The brochure should score better than 6 on the SMOG or better than 60 on the FRE. Both of these are easy to check with freely available on-line tools, such as this one: https://readabilityformulas.com/free-readability-formula-tests.php

- Consider brochure design. Focus on design elements that can improve accessibility, like those displayed in Table 1. Once you have a design you like, double check it against the MIDAS grading scale (described in detail by Krass et al., 2002), or a something similar. Most of these design elements can also be easily checked with built-in tools in freely available document readers, like Adobe Acrobat Reader.

- Use appropriate pictures. Use only pictures of newborns or screening equipment. Pictures of toddlers might be appropriate if they were located near text about milestones. Pictures of hearing aids or cochlear implants are likely to be confusing at this stage; parents of children with hearing loss will have ample opportunity in the future to see pictures of hearing devices and displaying them at this stage is likely premature.

- Use ‘did not pass’ to indicate a baby did not pass a hearing screening, rather than ‘refer’ because ‘refer’ has the potential to be confusing for many people.

20. Do your suggestions only apply to newborn hearing screening brochures?

The suggestion about picture appropriateness, of course, is very specific to newborn hearing screening brochures. We judged the degree to which the pictures were appropriate for newborn screenings, so pictures of toddlers were appropriate only in specific circumstances. For different contexts, the appropriateness of pictures would obviously vary and would be subject to expert opinion. Regardless of what was deemed appropriate or relevant, however, all brochures should only have relevant, clear pictures. Irrelevant, inappropriate, or distracting pictures can send confusing or mixed messages, and should be avoided.

The examination of the use of the word ‘refer’ to indicate a result is specific to situations where there are screenings, but newborn hearing isn’t the only time audiologists are involved with hearing screenings. No matter where you are doing screenings, I think it is safer to assume that the word would be confusing in almost any screening result context (e.g., school screenings, community health screenings, telephone- or computer-based screenings). Our study was specific to pregnant people who were asked to consider newborn hearing screenings, but there is the potential for confusion in almost any situation. Wherever there is the potential for confusion, it seems reasonable to take steps to reduce that confusion, in this case by using ‘did not pass’ instead of ‘refer.’

Readability and design choices also transcend the newborn hearing screening context. No matter the type of written material we are designing or revising, we should be striving to make it accessible by using clear, simple language and design features that promote legibility, interest, and understanding. Whenever we are working to develop written materials, I hope that we all work together to make healthcare information, including newborn hearing screening brochures, accessible to broad audiences.

Font size ≥10 points |

Serif font style |

High contrast ink (e.g., black ink on white background) |

Line space ≥ 2.2 mm |

Margins (≥0.5 in. sides and bottom; ≥0.25 in. at the top) |

True heading (heading on separate line from text) |

Headings sentence case (upper and lower case) |

Text sentence case (upper and lower case) |

Line length (≤40 letters) |

Use of bullets |

Bolding/box or summary to highlight important points |

No watermark behind text |

Pictures culturally appropriate |

Table 1. List of elements in the MIDAS evaluation of medical brochures (Krass et al., 2002).

References

Bess, F. H., & Paradise, J. L. (1994). Universal screening for infant hearing impairment: not simple, not risk-free, not necessarily beneficial, and not presently justified. Pediatrics, 93, 330 - 334.

Caposecco, A., Hickson, L., & Meyer, C. (2014). Hearing aid user guides: Suitability for older adults. International Journal of Audiology, 53, S43-S51. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.832417

Caposecco, A., Hickson, L., Meyer, C., & Khan, A. (2016). Evaluation of a modified user guide for hearing aid management. Ear and Hearing, 37, 27-37. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000221

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). 2019 Summary of Reasons for No Documented Diagnosis Among Infants Not Passing Screening. Atlanta, GA.

Hyde, M. L. (2005). Newborn hearing screening programs: Overview. Journal of Otolaryngology, 34, S70.

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (2019). Year 2019 Position Statement: Principles and guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs. Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 4, 1-44. https://doi.org/10.15142/fptk-b748

Krass, I., Svarstad, B. L., & Bultman, D. (2002). Using alternative methodologies for evaluating patient medication leaflets. Patient Education and Counseling, 47, 29-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00171-9

Manchaiah, V., Kelly-Campbell, R. J., Bellon-Harn, M. L., & Beukes, E. W. (2020). Quality, Readability, and Suitability of Hearing Health-Related Materials: A Descriptive Review. American Journal of Audiology, 29, 513-527. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJA-19-00040

Marchand, L. (March 22, 2017). What is readability and why should content editors care about it Retrieved August 18, 2021, from https://centerforplainlanguage.org/what-is-readability/#:~:text=Readability is about making your,part of your content management.

McLaughlin, G. H. (1969). SMOG Grading—–a New Readability Formula. Journal of Reading, 12, 639 - 646.

Mevorach, T., Cohen, J., & Apter, A. (2021). Keep calm and stay safe: the relationship between anxiety and other psychological factors, media exposure and compliance with COVID-19 regulations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062852

Ming, J., & Kelly-Campbell, R. J. (2018). Evaluation and revision of a tinnitus brochure. Speech, Language and Hearing, 21, 22-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2017.1316920

National Institutes of Health. (2018). New law to strengthen early hearing screening program for infants and children, from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/news/2017/new-law-early-hearing-screening-infants-and-children

Picou, E. M., McAlexander, S., Day, B., Jirik, K., Morrison, A., & Tharpe, A. M. (2022). An evaluation of newborn hearing screening brochures and parental understanding of screening result terminology. International Journal of Audiology. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2022.2068082

Shearer, A. E., Shen, J., Amr, S., Morton, C. C., & Smith, R. J. (2019). A proposal for comprehensive newborn hearing screening to improve identification of deaf and hard-of-hearing children. Genetics in Medicine, 21, 2614-2630. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0563-5

Citation

Picou, E. M. (2022). 20Q: Newborn Hearing Screening Brochures - Changes are Needed. AudiologyOnline, Article 28346. Available at www.audiologyonline.com