Learning Outcomes

After reading this course, participants will be able to:

- Discuss the difference between practice guidelines and standards.

- Identify self-assessment tools to use with hearing aid patients.

- List verification methods that can be used with hearing aid patients.

Gus Mueller: In the summer of 2020 I received an email from John Coverstone, AuD, who was contacting me relative to his role as the Executive Director of the Audiology Practice Standards Organization (APSO). He asked if I would be willing to be a member of a newly-formed APSO working group of subject-matter experts, who would be given the charge of writing a new hearing aid fitting standard for adults. I gave him an enthusiastic “yes.” I soon learned that I would be joining five other audiologists in the venture: Jason Galster, PhD, Cindy Hogan, PhD, Lindsey Jorgensen, PhD, Erin Picou, AuD, PhD, and Ryan McCreery, PhD. Shepherded by John, by the fall of 2020, we had carved out a draft standard, and after going through several reviews, months of public comments and legal counsel approval, the new standard was published on May 2, 2021 (APSO Standard S2.1, 2021).

Gus Mueller: In the summer of 2020 I received an email from John Coverstone, AuD, who was contacting me relative to his role as the Executive Director of the Audiology Practice Standards Organization (APSO). He asked if I would be willing to be a member of a newly-formed APSO working group of subject-matter experts, who would be given the charge of writing a new hearing aid fitting standard for adults. I gave him an enthusiastic “yes.” I soon learned that I would be joining five other audiologists in the venture: Jason Galster, PhD, Cindy Hogan, PhD, Lindsey Jorgensen, PhD, Erin Picou, AuD, PhD, and Ryan McCreery, PhD. Shepherded by John, by the fall of 2020, we had carved out a draft standard, and after going through several reviews, months of public comments and legal counsel approval, the new standard was published on May 2, 2021 (APSO Standard S2.1, 2021).

As expected, since its publication, stakeholders have had questions regarding why some things were included in the standard and why other things were not. I thought it might be helpful to have an informal discussion about the crafting of the standard and collect some thoughts from the working group. So, this month for our 20Q column we’ll have a roundtable discussion of the standard. Joining me are fellow group members Erin, Lindsey, and Jason. I’m also going to ask John to say a few opening words.

You’re probably thinking, don’t we already have published guidelines for fitting hearing aids for adults? The answer is, yes we do, but the key term here is guidelines. What about a standard? We’ll get to the difference shortly. Sticking with the general theme of hearing aid fitting guidelines, I don’t recall much talk about them in the 1970s or the 1980s. There was a 1960s document from the ASHA (ASHA Reports Number 2, 1967), but that was mostly ignored, as new clinical procedures had evolved. Things changed, however, in 1990, when a group of six audiologists attending the Vanderbilt Hearing Aid Conference wrote a consensus document containing the recommended components of a hearing aid selection procedure for adults. This was published in 1991 in both Audiology Today and the ASHA magazine (Hawkins et al, 1991a, Hawkins et al, 1991b). A few years later, we saw the hearing aid fitting guidelines from the Independent Hearing Aid Fitting Forum (IHAFF; Valente & Van Vliet, 1997). This was followed by the 1998 adult fitting guidelines from the ASHA (Valente et al, 1998), and later, in 2005, a lengthy document from the AAA (American Academy of Audiology Task Force, 2006). There also were some fitting guidelines from outside of the U.S., most notably from the International Society of Audiology (2005) and the British Academy of Audiology (2018). Additionally, there is the interesting 44-page document recently published by the ISO (ISO 21388:2020).

While hearing aid technology changes rapidly, what is considered “best practice” for the selection and fitting really has not changed too much from the Vanderbilt document of 30 years ago, and so for the most part, these guidelines are still relevant today. But these are guidelines, not a standard.

Back in May of 2020, we had Jenne Tunnell, AuD, here at 20Q (Tunnell, 2020). She provided an excellent explanation of why the profession of audiology needs standards. John, you’ve been with the APSO since the beginning, and since we have you here today, maybe you could give us a brief historical review?

John Coverstone: Thanks Gus, and great to be here. As you mentioned already, there are a number of guidelines in audiology in various areas of practice. A guideline is a document that describes how (that’s a key word) a procedure may be performed – often with multiple options. If you decide to fit a pair of hearing aids on an adult patient, the guideline will describe various ways to do each part of that process, often ranking the profession’s level of evidence or preference of methodology, and provide a detailed account of the steps involved, materials and equipment which may be used and may even address what outcomes are likely to be the consequence of each decision. Again, the key word is how. A guideline “guides” clinicians in how they should perform procedures.

A clinical standard, on the other hand, is more of a what document. Standards guide us as to what we should be doing with a specific patient in a specific circumstance. We label them a standard because we expect all providers to come to the same conclusion given a specific set of criteria – such as cochlear implant candidacy. Similarly, we have standards for what we do in fitting hearing aids. I should point out that APSO is in no way working to create standards, even though we admittedly say it that way sometimes. We are simply bringing experts together and using the existing research and accepted clinical practices to document the standards that already exist.

Mueller: So standards define the “what” and guidelines define the “how.” I got that part, but they have to be related, don’t they?

Coverstone: Theoretically, guidelines should be built on standards and they should, at some level, be in agreement.

Mueller: So with adult hearing aid fittings, we’re sort of doing it backward?

Coverstone: To some extent yes. A standard should be viewed as a minimum practice. A guideline will often describe more than one way to go about that task and, in some circumstances, may even recommend other practices as being more preferred than the standard. That is when we begin to get into best practices, which are the practices that achieve the best possible outcomes. Standards don’t address best outcomes; they address minimum acceptable practices.

Mueller: I know when we were working on this hearing aid fitting standard, we sometimes had trouble deciding how much detail or depth was needed for many of the items.

Coverstone: It is certainly possible to address every possible circumstance and patient situation in a standard. However, you can imagine that our subject-matter experts would be working for years to develop the standard document and the document would be 50 pages long! With the APSO, we strive to develop standards that are accessible and readable by both audiologists and non-audiologists, while remaining meaningful and useful.

I should also mention that standards may be used by the public and other healthcare providers to illustrate what an audiologist does. I really wish we had these in place 20 years ago, before so many other groups decided that audiologists are not all that necessary to the hearing aid fitting process.

Mueller: And, standards also protect the profession and those in it.

Coverstone: Most certainly! Medical history contains a number of court cases in which poor standards existed (or none existed) and the court decided on behalf of the profession what the standard should be. I personally do not want an attorney – however much I respect their knowledge of the law – to decide what I should be doing with patients in my clinic. Standards documents serve as an announcement of what audiologists should be doing. Yes, there is risk that some audiologists will refuse to follow these standards, but if someone is not even practicing to the minimum recognized in the profession, that risk existed anyway.

Mueller: Before I let you go, maybe you could say a few words about APSO since you were part of its inception?

Coverstone: During the 2017 AAA conference in Indianapolis, I was recording a podcast with co-host Jennifer Tunnell and our guests Gail Whitelaw and Lindsey Jorgensen. The topic was supposed to be about best practices in audiology and why so many colleagues seem reluctant to adopt them. However, we only got through part of the interview before we realized that we were talking about the wrong topic! How could we hope to move people to best practices when we don’t have standard practices?

The four of us kept in touch and came to recognize that we had been asking for years to have professional guidance developed, but it never seemed to be important enough or timely enough for our organizations to dedicate resources to it. We felt strongly enough to do our own thing and ultimately decided to create a central, apolitical organization that is dedicated to developing and maintaining standards documents in cooperation with all the other organizations in our profession.

APSO was legally incorporated in December, 2017, and began operating in earnest at the beginning of 2018. Although there was some, shall we say, surprise, from other professional organizations – including some misunderstandings as to what standards actually are and how they are different from other guidance that exists – we have been able to forge cooperative relationships across the professions. One of the benefits of being a separate organization is that our standards are completely open. We do not require any membership affiliation of those developing the documents. In fact, we openly invite every audiologist in the U.S. to participate in development as a subject-matter expert or to review and comment during the public comment period. APSO standards also remain freely available to anyone through our website (https://www.audiologystandards.org/).

Mueller: Thank you John. With all that great background information, I think we’re ready to dig into this new standard a little. Erin, Jason and Lindsey have been patiently standing by. Just to keep it simple, I think we’ll go through a few areas of interest from the standard, roughly in the order that they appear. The standard can be accessed at the APSO website, and we'll include it here for our discussion.

Hearing Aid Fitting for Adult & Geriatric Patients

- The hearing aid selection and fitting process is based on a comprehensive, valid audiological assessment. Each step of the selection and fitting process and the rationale is documented, where appropriate.

- Patient communication is conducted in a clear, empathetic manner consistent with the patient's communication mode, comprehension, and their health literacy level. Patient-centered and family-centered care is provided. The patient is encouraged to include communication partners (e.g., family members, significant others, companions) throughout the selection, fitting, and follow-up process.

- A needs assessment is conducted in determining candidacy and in making individualized amplification recommendations. A needs assessment includes audiologic, physical, communication, listening, self-assessment, and other pertinent factors affecting patient outcomes.

- Pre-fitting testing includes assessment of speech recognition in noise, unless clinically inappropriate, and frequency-specific loudness discomfort levels. Other validated measures of auditory and non-auditory abilities are considered, as appropriate for the individual patient.

- Fitting of bilateral hearing aids is the recommended protocol if the patient is a candidate for hearing aids in both ears and it is supported by the needs assessment.

- The hearing aid style and the ear coupling are chosen to be appropriate for the degree and configuration of the hearing loss. Style and coupling should reflect any physical limitations of the patient. Patient input regarding acceptable styles is taken into account.

- The recommended hearing aids include signal processing and features that support the patient’s listening needs. They have the appropriate gain and output, including reserve gain, to meet frequency-specific fitting targets as defined by a validated prescriptive method.

- Assistive technology and accessories are considered to facilitate accessibility to other devices and to satisfy the patient’s listening and communication needs.

- An assessment of initial product quality is completed, using standard electroacoustic measures to verify either manufacturer or published specifications.

- Hearing aids are fitted so that various input levels of speech result in verified ear canal output that meets the frequency-specific targets provided by a validated prescriptive method. The frequency-specific maximum power output is adjusted to optimize the patient’s residual dynamic range and ensure that the output does not exceed the patient’s loudness discomfort levels.

- Following individualized verification of hearing aid gain and output, if the fitting is not acceptable to the patient, minor deviations in gain and output may be necessary.

- Orientation is device- and patient-centered and includes use, care, and maintenance of the hearing aid(s) and accessories.

- Counseling is conducted to ensure appropriate adjustment to amplification and to address other concerns regarding communication. Additional rehabilitative audiology is recommended if deemed appropriate.

- Hearing aid outcome measures are conducted. These may include validated self-assessment or communication inventories and aided speech recognition assessment.

- Short- and long-term follow-up is conducted to ensure that post-fitting needs are addressed. This includes updated audiological assessment, hearing aid adjustments and routine maintenance as needed to ensure the devices are functioning properly and appropriately for the patient.

Mueller: One of the first items of the standard is the recommendation for a needs assessment. It’s a pretty general statement. Do you think we should have been more specific, by actually naming some assessment tools to accomplish this? And since I have you all here, do you have scales or procedures that you would recommend for routine use?

Jason Galster: First, let me say thanks Gus for inviting us to your roundtable, and before we dive-in, a second thanks for your contributions to this standard of practice. This was an impressively productive (and brilliant) working group.

Jason Galster: First, let me say thanks Gus for inviting us to your roundtable, and before we dive-in, a second thanks for your contributions to this standard of practice. This was an impressively productive (and brilliant) working group.

As John so nicely described, the standard of practice scope is intended to be broad, outlining the core elements of a treatment plan. This breadth of scope kept us from making a recommendation that included examples or specific recommendations. That said, many of us have developed preferences based on clinical and scientific experience. Personally, I appreciate the flexibility of the COSI as a needs assessment. It’s a tool that only gets sharper with use. The open-ended outcome categories allow you document desired goals at the time of pre-fitting and track progress against those goals through the rehabilitation process.

Mueller: I believe surveys have shown that the COSI is the most commonly used needs assessment tool. It’s a little ironic, that an assessment scale that has become that popular basically starts off as a blank page! That Harvey Dillon guy who developed it is pretty shrewd. So Lindsey . . . your thoughts on needs assessments?

Jorgensen: As Jason mentioned, I don’t think it’s the purpose of the standard to list specific tests or procedures—who knows, during the life of the standard, better tests may emerge. I think that any well-designed needs assessment adds to the success of the hearing aid fitting. I use the HHIA/HHIE to determine how the person perceives their hearing loss and then I also do a “rate from 1-10 your hearing difficulty” per Catherine Palmer’s research (Palmer et al, 2009). And yes, I also often use the COSI to obtain patient-specific goals.

Mueller: You mention the use of the HHIE/A. That certainly is a self-assessment inventory that has withstood the test of time—about 40 years since the intro article I believe. There seems to be increased interest recently in using this measure to assist in hearing aid candidacy. Larry Humes, for instance, recently has done some writing on this topic (e.g., Humes, 2021).

Erin Picou: I think there’s good reason why the HHIE/A have persisted. For me, I like the HHIE/A as part of the needs assessment because the questionnaire addresses the impact of hearing loss on someone’s social and emotional well-being. As we move towards holistic models of hearing healthcare (e.g., helping the whole patient rather than focusing on the ear), it becomes critically important to address not only auditory function, but also the social and emotional aspects of hearing loss. The HHIE/A provides valuable information that we can use to supplement the information we gain from audiometric testing – information that tells us how a patient is managing more generally.

Galster: Regarding the use for candidacy, we’ve been following that area of work with great interest. To date, the data suggest that audiologists may be able to use a slightly modified version of the HHIE, to triage hearing aid candidates into different rehabilitation pathways, specifically a self-treatment path that might include over-the-counter hearing aids or a clinical treatment path in which hearing aids are prescribed by an audiologist following best practices. While audiologists may hesitate at the concept, it presents an opportunity to increase clinical efficiency by reserving time for patients whose needs are best met by the expert audiologist. Of course, these concepts are still young and this or other models of triaging require systematic validation.

Mueller: Part of the development of this standard was an extended period of public review—practicing audiologists had the opportunity to comment on the initial draft, which was helpful in our work creating the final product. One area that drew some discussion was our recommendation for pre-fitting speech-in-noise testing. I have trouble coming up with a reason why this would not be standard practice.

Jorgensen: Me too. We conduct speech-in-noise testing for essentially all of our hearing aid patients. I use it for several reasons. My primary reason is that I want to validate the patient’s complaint. As we all know, the primary complaint of most patients is difficulty hearing in background noise. By only conducting speech-in-quiet testing, we are not addressing or even evaluating their primary complaint.

Galster: And also, the literature in this area indicates that some patients present with speech recognition in noise ability that is not clearly predicted by their audiometrics or speech recognition in quiet. As such, understanding the handicapping effects of listening in noise can meaningfully direct the treatment plan, guiding the focus of counseling and selection of relevant technologies (e.g., remote microphones, TV assistive devices, or more aggressive noise reduction).

Mueller: Right, regarding patients with normal pure-tone thresholds, that so-called “hidden” hearing loss might not be so hidden if everyone received a speech-in-noise test. Audiologists, however, do seem to have a love affair with speech testing in quiet. Richard Wilson’s work comparing WIN findings to NU-6 in quiet always stands out to me, maybe because he had an “n” of 3,430 (Wilson, 2011). What he found was that approximately 70% of the group had NU-6 performance in quiet that was good or excellent, but of that 70%, only 7% had normal WIN scores. On the other hand, of the 6% of the total group who had normal performance on the WIN, 98.5% also had normal performance for speech-in-quiet. So if speech-in-quiet scores rarely predict speech-in-noise performance, and speech-in-noise scores nearly always predict speech-in-quiet performance, it would seem pretty simple to decide which one of the two tests to use.

With that, let’s move on to another pre-fitting test that also generated some discussion during the public comment period, and that was the assessment of frequency-specific loudness discomfort levels (LDLs). This is something that we included back in the 1990 Vanderbilt Guidelines, so it’s nothing new, but there were some who questioned whether this should be in the standard.

Picou: Allowing hearing aids to produce an output that is uncomfortably loud is a sure way to make a hearing aid user unhappy. Making sure the hearing aid output is below the patient’s LDLs is an easy way to ensure the hearing aid is not uncomfortably loud. It makes sense to me that, in order to check that a hearing aid is not exceeding a patient’s LDL, the LDL would have to be frequency-specific, since the MPO measure is frequency-specific.

Mueller: Sure. How else would you know where to set the AGCo kneepoints?

Galster: A central role that the audiologist plays in prescribing hearing aids is individualization of the hearing aid settings—MPO is one of those settings. While all prescriptive formulas for hearing aids include predicted output targets, these are based on averages and not individualized. Measurement of frequency-specific LDLs, and their use in programming output, will improve acceptability for many hearing aid fittings. Additionally, the results of these LDL measurements can be entered into real-ear systems to generate individualized maximum output targets for the REAR85 verification measure.

Mueller: Jason, you mention the problem of using “average” values. I think it’s always helpful to go back and look at the findings from Ruth Bentler and Laura Cooley (2001; LDL data from over 700 ears) who found that for common cochlear hearing losses of 40-60 dB HL, LDLs had a ~50-55 dB range, with only about 30% falling within +/- 5 dB of average. That’s not good enough for me. And let’s not forget, with the DSL prescriptive method, the patient’s frequency-specific LDLs also influence the fitting targets that are generated for speech mapping verification.

Jorgensen: I’m afraid that many audiologists just assume that the manufacturer’s fitting software will generate MPO values that are “okay” based on the audiogram.

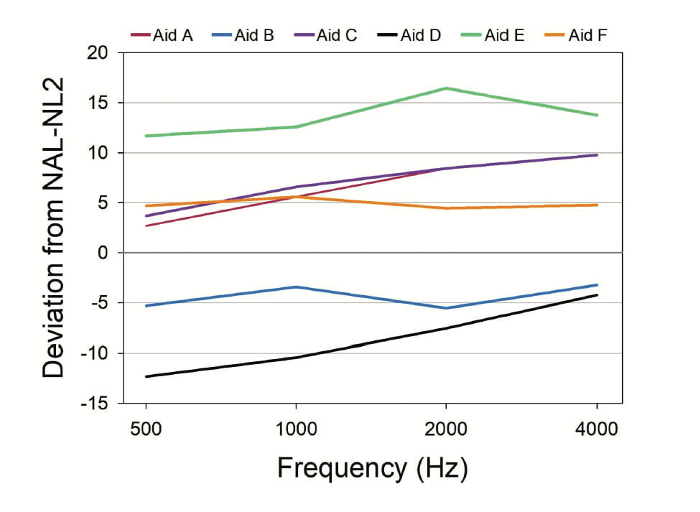

Mueller: You’re probably right, but I would say that that approach is very risky. And not because of the “average values” issue we were just discussing. A few months ago I worked on an MPO project with Yu-Hsiang Wu and Elizabeth Stangl at the University of Iowa (Mueller et al, 2021). Let me briefly describe one of our findings. We selected the premier model hearing aid for each of the 6 leading manufacturers, and entered a common downward-sloping hearing loss into the software; 30 dB in lows dropping to 60-70 dB in the highs. We selected the NAL-NL2 as the fitting method. Now, you might think that since we selected the NAL-NL2 prescription, the average values of this prescriptive method would be the MPOs that were programmed by the manufacturers. That was not the case. What happened is what you see in Figure 1. The “zero line” is the NAL-NL2 prescribed 2-cc MPO obtained from the NAL-NL2 stand-alone software for the sample audiogram. Note that a given patient could have an MPO that differed by nearly 25 dB simply based on what manufacturer was selected. This relates directly to why frequency-specific LDLs are needed, and why audiologists, not manufacturers, need to program the MPO.

Figure 1. Shown are the deviations from the prescribed MPO values of the NAL-NL2 (0 dB reference line in chart) for the frequency-specific MPOs that were displayed in the fitting software for the sample audiogram. From: Mueller, Stangl, & Wu, 2021. Used with permission of Hearing Review.

Picou: One final thing regarding LDL testing. There were some comments questioning the reliability of the measurements, but that really isn’t an issue if you use the appropriate loudness anchors, instructions and procedures, such as those of Robyn Cox, adopted by the IHAFF protocol. For example, using the Cox approach, Catherine Palmer and George Lindley (1998), reported a mean test-retest difference of 2.6 dB across five test frequencies for the #7 Uncomfortably Loud rating.

Mueller: Good point. That’s about the same test-retest reliability as we see when conducting clinical pure-tone thresholds, which I hear is a fairly popular test procedure!

The standard states that there should be an assessment of initial product quality using standard electroacoustic measures. This was pretty common years ago, but I get a sense it’s not so common today. There were some good reasons, of course, why we included it in the standard.

Galster: There certainly were. This is an important distinction that comes down to the topic of quality control. Before a new hearing aid leaves the manufacturer, a series of acoustic tests are completed to ensure it meets specifications. The purpose of in-office electroacoustic testing is further assurance that device quality is maintained during shipping and on receipt by the audiologist.

Picou: I agree. The electroacoustic evaluation in a coupler will alert us to things that potentially went awry during the manufacturing or shipping processes that we might otherwise miss during probe-microphone measures, which are conducted for a different purpose. For example, is the hearing aid inherently noisy? Does the battery drain too quickly? Answers to these questions would be nearly impossible to detect during probe-microphone verification. From a practical standpoint, by doing electroacoustic evaluation of the hearing aid before the patient’s appointment, you can make sure the hearing aids are generally working well, and save yourself time and a headache if you discover the hearing aid is malfunctioning after you fit it to the patient or the patient brings it back.

Mueller: And I’m pretty sure that there is a high correlation between the number of problems occurring at the time of the fitting, and the miles the patient traveled for the appointment.

Jorgensen: In our clinic in South Dakota, that easily could be 50 miles or more! We check all of the specs on our hearing aids when they arrive from the manufacturer, and some do arrive not meeting ANSI standards. To me, one of the most important measures during this quality control assessment is the directional microphone performance, as this is this is an important feature for many patients.

Mueller: I believe it’s the last item of our standard that talks about post-fitting hearing aid maintenance. Ensuring that the directionality is working properly is an even more important measure then, as debris in microphone ports is pretty common. And current test-box equipment allows us to do that assessment very easily.

So moving down the list on the standard, we’ve now reached verification, which of course is accomplished through the use of probe-mic measures, or real-ear measures (REM), as they are commonly called. This too has been part of adult fitting guidelines for 30 years. Yet, I suspect there are a fair number of audiologists out there who don’t even own the equipment.

Picou: I understand that two of the commonly cited obstacles to routinely conducting probe-microphone verification relate to clinic time and equipment cost. I think the equipment has come a long way in the last decade - we now have some automated options that can cut down on clinical time. There are also some relatively affordable options available. I encourage anyone who is on the fence about obtaining (or using) probe-microphone equipment to re-examine the systems that are currently available.

Mueller: And Erin, I suspect you remember the historic Mueller and Picou (2010) probe-mic survey?

Picou: Oh yes, I have a copy under my pillow.

Mueller: To me, one of the most interesting findings of that survey was that for the audiologists who participated, around 400 I believe, 45% reported conducting probe-mic verification at least 50% of time. When we then looked only at the respondents who had the equipment, the regular use rate only went up to 58%. So having the equipment available might not be as important as we sometimes think.

There is another finding from that survey that I think is important. We often hear audiologists talk about “doing REM.” The standard clearly states: “Hearing aids are fitted so that various input levels of speech result in verified ear canal output that meets the frequency-specific targets provided by a validated prescriptive method.” The key here is that it’s not just conducting the testing, but it’s the verification to validated targets. It’s not simply “doing REM” (See Mueller, 2005). Moreover, the term verification is a little misleading, as fitting to prescriptive targets usually involves considerable programming. As has been frequently reported, most manufacturer’s software attempt at fitting to prescriptive targets is not clinically acceptable, especially for soft inputs (for review see Mueller, 2020).

Picou: As I recall, in our survey, less than ½ of the respondents said that the primary reason that they were conducting real-ear measures was to “match to prescriptive targets.”

Galster: To my way of thinking, the prescriptive fitting of hearing aids clearly requires real-ear measurement of the hearing aid output. The absence of equipment or the patient’s blind acceptance of first-fit settings do not change this fact. With cost being one of the more commonly cited reasons for excluding real-ear measurement, it should be noted, as Erin mentioned, that options for less expensive measurement systems have been introduced in recent years. If cost is a primary obstacle in your clinic, the affordability of today’s introductory systems may be surprising, and used systems can be purchased or at a substantial discount.

Mueller: Or, if your budget is really tight, there are leasing deals for used equipment that have monthly charges that are not much more than a bottle of good wine. The main issue really is, if you’re not doing probe-mic verification, what’s your Plan B to ensure that you have an appropriate fitting? I can’t think of one. How about you, Lindsey?

Jorgensen: Knowing that there are some audiologists who don’t have the necessary equipment, I really struggle with this. I have tried to come up with a way for people to do some type of similar subjective evaluation of at least aided audibility, but I just can’t figure out a way. Aided soundfield testing is fraught with all sorts of problems. Validation is subjective, and a person going from not hearing much, to hearing more, even if it’s far from optimal, will still probably give a favorable rating. Just look at all the patients who are willing to use the proprietary fitting, which we know isn’t optimal. I’m like you Gus, I don’t think there is a Plan B.

Mueller: Let’s move on to validation, which is another major area of the standard. Like other areas, we didn’t give specific examples of different self-assessment scales or inventories—there certainly are many validated procedures to choose from.

Galster: You’re right, in research we’ve seen a tsunami of interest in measurement of outcomes during daily life. In terms of clinical measures, we are limited to retrospectively asking patients about their listening experience. Options for outcomes measures span a broad range, from the familiar IOI-HA, HHIE, GHABP, COSI and APHAB to a wide range of less clinically common alternatives. We should expect the forward march of technology and ubiquity of mobile applications to introduce new measure that can be completed at any time with the results being reported back to the clinic and prescribing audiologist.

Mueller: You mention mobile applications. It was not that long ago that EMA (ecological momentary assessment) for real-world hearing aid validation was something reserved for research projects. Today, most manufacturers have some form of it as a smart phone app that can be used with their products.

Picou: As Jason said, there are a lot of great options out there and the point for me is to make sure you’re measuring outcomes that relate to the whole person, not one specific desired domain, like audibility of soft speech. Something like the HHIA/E, which looks at social and emotional well-being by focusing on the consequences of hearing loss in someone’s life is a good choice. We discussed the COSI earlier related to needs assessments, but this also is another great real-world outcome option which helps a patient and an audiologist work together to identify specific listening situations of concern.

Mueller: So we’re starting to wind down our little roundtable discussion. We only had time to focus on some of the major items, but do any of you want to comment on something that we skipped?

Picou: Yes, I do. One of the things that in the standard that I was really happy to include is Item #2, which is the focus on patient-centered care as fundamental to all stages of the hearing aid fitting process. This focus on the patient and the family is really important as our models of hearing healthcare morph from medical models (biomedical focus) to holistic models (biopsychosocial focus). It’s becoming clear that the holistic models of hearing healthcare have the potential to result in better outcomes because the patients are invested and their partners (spouses, family members, friends, children) are involved. There’s a growing literature base supporting this style of hearing healthcare and I was really happy to include this in the standard.

Mueller: Thanks Erin, glad you brought that up and you make some great points. The standard we’ve been discussing today is for adults, but the move toward more holistic care also applies to our pediatric patients. I know that a standard for pediatric fittings is planned, or maybe the working group already has started? I assume that it will include some of the same general areas that we have in this standard? Jason, I think you have an update on that project?

Galster: The pediatric subject-matter experts recently have started to address this exact question. We expect that the pediatric standard of practice will be somewhat different. For instance, children at early stages cannot provide feedback regarding listening ability or needs, which may require a substantial change in diagnostic approach and reliance on parental report. This represents a fundamental difference in the role of needs assessment between the two standards, and only touches the broader extent of differences. The pediatric standard of practice will thoroughly consider the needs of children and reference a different base of knowledge and literature. Of course, there are complements between the two standards, but we are always conscious of the specific needs presented by the pediatric population.

Mueller: Given the limited time we have left, I might as well toss out the big question. Get out your crystal ball. Polish it. There has been a lot of talk about what is good practice and what is best practice for fitting hearing aids for many years. There are well-written guidelines to help us accomplish this. But yet, it doesn’t seem like we have all the stakeholders on board. Will this new standard help?

Jorgensen: I certainly hope so. I hope that I see the day that all patients, practitioners, and organizations that reimburse for hearing aids expect hearing aids to be fitted to these minimal standards.

Picou: One of the things I really like about this standard is that we are sharing the elements that we believe are the minimum for clinical practice, but there are many ways to achieve hearing aid fittings that meet this standard. We didn’t write a protocol and aren’t trying to make everyone practice in the same way. I think this standard has the potential to unite us in our aims, and let us achieve these aims in the way we see most appropriate as individual audiologists.

Galster: I think this standard will make a difference. In fact, several practices in the U.S. already have reviewed these recommendations to update their own guidelines. International groups have contacted the APSO board to inquire about referencing this standard in hospital practice guidance. These examples show global awareness and interest in the standard of practice for fitting hearing aids. We’re confident that this uptake will continue; as far as I know, at least for those of us in the U.S., it is the only hearing aid fitting standard of practice available to clinical audiology.

Mueller: Thanks all, it’s time to say good-bye. Your contributions today are much appreciated, and also thanks for all your time and effort in developing the standard over the past year.

We do, however, have a special treat before we close. Michael Valente, PhD, has stopped by. As you all probably know, Mike was involved in the development of the IHAFF protocol, the ASHA hearing aid fitting guidelines, and also was the Chair of the group writing the AAA adult fitting guidelines (American Academy of Audiology Task Force, 2006). Mike, you certainly know all about guidelines, but today we’re talking about a new standard. Sort of the same, but different. I’ll toss the same question out to you: Will this new standard move the needle?

Mike Valente: I just happened to be in the 20Q neighborhood! My congratulations to John and all the subject-matter experts for creating and disseminating this new APSO hearing aid fitting standard. Implementing the steps within this standard certainly will improve the care to our patients. Equally important is that the standard may have been introduced at the perfect time, as many audiologists are feeling that the importance of their skills in the hearing aid fitting process is being undermined by competition from DTC, OTC, hearables and PSAPs as alternate methods to procure hearing aids.

Mike Valente: I just happened to be in the 20Q neighborhood! My congratulations to John and all the subject-matter experts for creating and disseminating this new APSO hearing aid fitting standard. Implementing the steps within this standard certainly will improve the care to our patients. Equally important is that the standard may have been introduced at the perfect time, as many audiologists are feeling that the importance of their skills in the hearing aid fitting process is being undermined by competition from DTC, OTC, hearables and PSAPs as alternate methods to procure hearing aids.

Back to your question - will the new standard move the needle? Audiologists counseling patients about this standard and its use could act as a beacon for patients. By that I mean that they can help patients to better understand that a hearing aid is a product, but a well-fitted hearing aid is the sum of the hearing aid plus the services provided by audiologists following the APSO standard. And, they can promote the fact that adherence to the services specified in the standard will lead to a more effective listening experience.

Mueller: Thank you, Mike. You heard it here. Words to heed.

References

American Academy of Audiology Task Force. (2006). Guidelines for the audiologic management of adult hearing impairment. Available at www.audiology.org

ASHA Reports Number 2. (1967) A conference on Hearing Aid Evaluation Procedures Castle W.E (Ed). 1-71.

Bentler R, Cooley L (2001) An examination of several characteristics that affect the prediction of OSPL90 in hearing aids. Ear Hear 22(1), 58-64.

British Society of Audiology. (2018). Guidance on the verification of hearing devices using probe microphone measurements. Available from https://www.thebsa.org.uk/resources/

Hawkins, D. Beck, L. Bratt, G. Fabry, D. Mueller, HG. Stelmachowicz, P. (1991a) The Vanderbilt/Department of Veterans Affairs 1990 Conference Consensus Statement: Recommended components of a hearing aid selection procedure for adults. Audiology Today, 3, 2, 16-18.

Hawkins, D. Beck, L. Bratt, G. Fabry, D. Mueller, HG. Stelmachowicz, P.(1991b) The Vanderbilt/Department of Veterans Affairs 1990 Conference Consensus Statement: Recommended components of a hearing aid selection procedure for adults. ASHA, 33, 4, 37-38.

Humes L. (2021) An Approach to Self-Assessed Auditory Wellness in Older Adults. Ear and Hearing, 42(4), 745-761.

International Society of Audiology. (2005). Good practice guidance for adult hearing aid fittings and services - Background to the document and consultation. Available from: https://www.isa-audiology.org/ members/pdf/GPG-ADAF.pdf External link

ISO 21388:2020(E). Acoustics—Hearing Aid Fitting Management (HAFM)

Mueller, H.G. (2015, May). 20Q: Today's use of validated prescriptive methods for fitting hearing aids - what would Denis say? AudiologyOnline, Article 14101. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com

Mueller, HG. (2020) Perspective: Real ear verification of hearing aid gain and output. GMS Z Audiol (Audiol Acoust), 2:Doc05. doi:10.3205/zaud000009

Mueller, H.G. & Picou, E.M. (2010) Survey examines popularity of real-ear probe-microphone measures. Hearing Journal, 63(5), 27-32.

Mueller G, Stangl E, Wu Y-H. (2021). Comparing MPOs from six different hearing aid manufacturers: Headroom considerations. Hearing Review, 28(4), 10-16.

Palmer C, Solodar H, Hurley W, Byrne D, Williams K (2009) Self-perception of hearing ability as a strong predictor of hearing aid purchase. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 20 (6), 341-347

Palmer C, Lindley G. (1998) Reliability of the contour test in a population of adults with hearing loss. Journal of American Academy of Audiology, 9(3), 209-215.

Tunnell, J. (2020). 20Q: Why we need an audiology practice standards association. AudiologyOnline, Article 26955. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Valente M, Van Vliet D. (1997) The Independent Hearing Aid Fitting Forum (IHAFF) Protocol. Trends Amplif, 2(1), 6-35.

Valente, M., Bentler, R., Seewald, R., Trine, T., & Van Vliet, D. (1998). Guidelines for hearing aid fitting for adults. American Journal of Audiology, 7, 5-13.

Wilson R (2011). Clinical experience with the words-in-noise test on 3,430 veterans: Comparisons with pure-tone thresholds and word recognition in quiet. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 22(7), 405-423.

Citation

Mueller, H.G., Coverstone, J., Galster, J., Jorgensen, L., & Picou, E. (2021). 20Q: The new hearing aid fitting standard - A roundtable discussion. AudiologyOnline, Article 27938 Available at www.audiologyonline.com