From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

Our 20Q this month is about new guidelines. Most would agree that clinical guidelines in audiology are a good thing. You all are probably familiar with the guidelines regarding the measurement of pure-tone thresholds, published several decades ago. Specifically stated is the recommended psychophysical procedure, which is “down in 10 dB steps—up in 5 dB steps.” Okay, admit it, you’ve all gone “down in 5 dB” at one time or another. But hey, they are guidelines, not standards.

Sometimes, however, clinical guidelines can serve as the foundation of a standard, or at the least, a document with teeth. In 1990, as part of the Vanderbilt/VA hearing aid conference, a group of six audiologists put together a set of guidelines titled: Recommended Components of a Hearing Aid Selection Procedure for Adults. These guidelines were published in both Audiology Today and Asha in 1991. Most notably, these were the first set of guidelines recommending that probe-microphone measures be used for hearing aid verification. Today, the College of Speech and Hearing Health Professionals of British Columbia has a Clinical Protocol that states that probe-microphone verification must be conducted for all hearing aid fittings. Failure to do so can result in disciplinary action.

So, we never know exactly how guidelines might evolve. Our topic here at 20Q relates to the new cochlear implant guidelines. We say “new,” but they actually are the first comprehensive evidence-based guidelines on the topic. Putting together guidelines such as these requires a lot of effort from a dedicated team, and the American Academy of Audiology found such a team—actually, because of the length of the project, two teams! We’ve brought in the Chair of “Team 2” to discuss the guidelines with us.

Jessica J. Messersmith, PhD, is an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at the University of South Dakota (USD), a place she has called home for 10 years—not too far from her student training days at the University of Nebraska and Boys Town.

Dr. Messersmith is involved in many state and national professional activities including the South Dakota EHDI program, multiple committees for the AAA, and the ASHA Academic Affairs Board. She has worked with cochlear implants the past 15 years, and published extensively on the topic. Her current line of research focuses on clinical practices in the cochlear implant clinic and improving the outcomes of children with cochlear implants through these practices.

Over the years, Jessica has been involved in several leadership development activities with both the AAA and the ASHA. I’m sure it required all the leadership skills she could muster to keep her committee moving forward for the past few years, and to produce the finished product. We thank her and her team for their efforts.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: An Overview of the New Cochlear Implant Practice Guidelines

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Define the concept of clinical practice guidelines.

- Discuss a mechanism for appraising published research.

- List recommendations for clinical practice related to cochlear implants.

Jessica Messersmith

Jessica Messersmith 1. I’ve certainly heard of them, but what exactly is a practice guideline?

Clinical practice guidelines, as defined by the National Institutes of Health (2017), are a statement document that provides recommendations for specific diagnostic and treatment approaches as they apply to diagnosis and management of a particular condition. A more modern definition has been offered: “Guidelines are a convenient way of packaging evidence and presenting recommendations to healthcare decision makers” (Treweek et al., 2013). For example, you might recall that back in 2013, the American Academy of Audiology issued practice guidelines focused on the fitting of hearing aids to children (American Academy of Audiology, 2013). These guidelines have been used by many clinics and organizations as a foundation to establish best practice documents.

2. That sounds like a “standard” to me. How do practice guidelines differ from standards?

The terms guidelines, standards, and protocol should not be interchanged. Standards are rigid and provide a specific process. Clinical practice guidelines provide research-based information that can assist practitioners in clinical decision making. Clinical practice guidelines can provide clinicians an understanding of the evidence related to a certain topic that the clinician can then use to make clinical decisions. It is possible that some standards will incorporate portions of existing practice guidelines.

3. If it isn’t a standard, what purpose does a practice guideline serve?

The purpose of a practice guideline is to provide evidence-based recommendations to clinicians for use in clinical care. In health care, research is generated at a faster pace than the average clinician can read and evaluate. Review and appraisal of research is necessary, however, for the implementation of evidence-based care. This conundrum between the need for critical appraisal of research and the limited time to do so places the individual clinician in a difficult situation. This is where clinical practice guidelines gain their importance. A practice guideline document reflects a systematic review of published literature on a particular topic, a critical appraisal of the relevant literature, and a compilation of these findings into a set of recommendations for clinical practice. Speaking more generally, guidelines serve to improve the effectiveness of care, reduce variations in clinical practice and diminish clinical practice mistakes (Kredo et al., 2016).

4. Why was a new practice guideline needed for cochlear implants (CIs)?

First, it’s important to point out that while I’m referring to this guideline as “new”, it really is the first comprehensive guideline on the topic. Research related to cochlear implants, like other areas of health care, is generated at an outstanding rate. A quick Google Scholar search for publications using the search term “cochlear implants” yields nearly 2,500 hits for publications thus far in 2019! It would take a practicing clinician a great deal of time to sort through these publications, determine which are relevant to clinical practice, critically appraise them, and then identify potential clinical applications. Practicing clinicians do not have the time.

Clinical practice guidelines serve an essential role in quality medical practice. As I mentioned, the American Academy of Audiology Cochlear Implant Practice Guidelines document represents the first clinical practice guidelines document put forth by any national-level entity, related to the care of individuals who utilize cochlear implants and the programming of the devices.

5. Who do you see as the target audience for the practice guidelines?

The primary target audience is audiologists working with individuals who utilize cochlear implants. It is important to recognize, however, that other individuals and entities may be a secondary audience, as practice guidelines may be referenced for policy and health insurance coverage decisions. The guideline can help inform physicians, reimbursement agencies, government agencies, the hearing health-care industry, patients, families, and caregivers about what research evidence demonstrates as the current best practices related to cochlear implant care.

6. How was the practice guideline document created?

This document originated as an extensive review of literature prepared by the American Academy of Audiology Task Force on Guidelines for Cochlear Implants that was initiated in 2015. In 2017, the composition of the task force changed and was renamed the American Academy of Audiology (AAA) Task Force on Cochlear Implant Practices. The final document, while influenced by the document created by the 2015 task force, represents an updated review of the evidence, which allowed for a comprehensive compilation of current knowledge in a format consistent with other AAA guidelines documents.

The process of developing the guideline was evidence-based when possible. Evidence-based practice integrates clinical expertise with the best available clinical evidence derived from systematic research. Where evidence was ambiguous or conflicting, or where scientific data are lacking, the clinical expertise of the task force was used to guide the development of consensus-based recommendations.

In the literature search, task force members first sought to identify studies at the top of the hierarchy of study types. Once definitive clinical studies that provided valid relevant information were identified, the search stopped. The search was extended to studies/reports of lower quality only if there were no higher quality studies. Found evidence was then grouped by topic and the evidence was critically appraised and graded. Through extensive discussion and review of the literature, the task force came to a set of recommendations for clinical practice in each of the topic areas.

A final draft version of the document was submitted to and approved by the AAA Guidelines and Strategic Documents Committee. The guideline was available for peer review for 30 days after which the task force reviewed and responded to all peer review comments. This then led to a final document that was submitted to the Board of the American Academy of Audiology for approval. The approved document is then the accepted cochlear implant guideline document for the Academy and was placed on the webpage.

7. You mention appraisal of published evidence. Would you elaborate on what that entails?

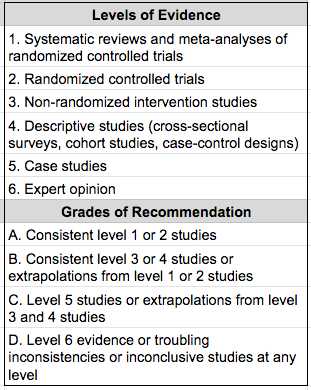

Critical appraisal of evidence is a foundation for evidence-based research. In order to determine what research to infuse in clinical practice and the weight by which this research should impact clinical decisions, the clinician must determine the “validity, clinical significance, and applicability of evidence” (Cox, 2005). To do so, readers must rate the level of evidence, assign a grade for the consistency of results, and identify the setting of the research. A table denoting the levels of evidence and the letter grading of consistency of result is provided in Table 1. In addition to grading the evidence and assigning it a level, it was determined if the evidence was Efficacy (EF) or Effectiveness (EV). EF is evidence measured under “laboratory or ideal” conditions and EV is evidence measured in the “real world.”

Table 1. Explanation of levels of evidence and grades of recommendation.

8. Are most of the recommendations in the new CI guideline based on Level 1 or 2 studies? I see they get a grade of “A.”

There were several Level 1 and 2 studies, but there wasn’t always that level of evidence. We found a lot of research that we could not classify as higher than Level 3 or Level 4 studies.

9. What would be an example of an area where high level evidence simply doesn’t exist?

There are several recommendations where a high level of evidence didn’t exist. For example, one common clinical practice is to perform certain measures of cochlear implant function intra-operatively under the assumption that information about device integrity and when to use a back-up internal device can be gained. There really isn’t a high level (e.g. Level 1 or Level 2) of evidence to support that practice.

10. Do you have suggestions for how I might start to implement the practice guidelines into my clinic?

The guideline addresses the technical aspects of the cochlear implant candidacy evaluation, objective measurements, device programming, and follow-up care. The guideline provides the evidence base from which clinicians can make individualized decisions for each patient. It is not intended to dictate precisely how cochlear implants should be programmed for each individual. Thus, from this guidelines document, clinics can draw from the recommendations and evidence to inform their clinical protocols. As the task force was working on the document, we kept reminding ourselves that the guideline was not to be a cookbook for clinical practice. Rather, we created a document that will allow clinicians to understand what components should be considered and why these certain components should be considered.

11. What are the main topic areas covered by the practice guidelines?

The following areas were addressed within the document: signal processing of the device, audiological candidacy criteria, surgery considerations for the audiologist, device programming, outcomes assessment and validation, follow-up schedule, care beyond device programming, and billing.

12. You mention audiology candidacy criteria. I haven’t been following this area closely, but doesn’t that keep changing?

The short answer is yes, candidacy criteria is continually changing. Candidacy is strongly influenced by the likelihood of improved hearing and evolving criteria. Across the time period of FDA-approved cochlear implant use, determination of appropriateness for cochlear implantation has become less centered on audiometric thresholds, and more centered on performance with amplification (hearing aids). Cochlear implants should be considered for those individuals whose hearing loss cannot be adequately addressed through acoustic amplification (e.g. hearing aids) alone.

Since receiving Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 1984, the criteria for cochlear implantation has expanded to include individuals of younger ages and those with more residual hearing. Utilization of cochlear implants now includes bilateral implantation (receipt of a cochlear implant in each ear) and electroacoustic cochlear implants (some frequencies transmitted via acoustic amplification and other frequencies transmitted via electrical stimulation).

Cochlear implants may be appropriate for individuals outside of the FDA-approved indications. For example, although not specifically covered under FDA approval, cochlear implants are being successfully utilized with individuals with unilateral deafness or asymmetric hearing loss where only the ear to be implanted meets cochlear implant criteria.

Determination of the appropriateness of cochlear implants within and beyond FDA-approved criteria should be made by the team of professionals at the cochlear implant center, as well as by the individual, or family of the individual, who might receive the cochlear implant.

13. You mention that one section is surgical considerations for the audiologist? Audiologists have surgical considerations?

Although audiologists are not performing the surgical procedure, there are a number of issues related to surgery which the audiologist needs to be aware. There are certain tests of equipment and cochlear function that can be completed intra-operatively. The audiologist may be performing these or interpreting results from this testing. Results from some of these measures may provide information that may impact the audiologist’s programming decisions, post-operatively. Also, knowledge of the surgical procedure will allow the audiologist to guide the patient through the process and understand when to refer concerns to the surgeon.

14. It seems to me that of the areas you listed, programming is one of the most important. What are the recommendations in this area?

You’re right, device programming is one of the most critical elements of a recipient’s success with a cochlear implant and is heavily influenced by the programming audiologist’s knowledge and experience with cochlear implants. The programming section provides recommendations outlining the possible procedures that can be followed or performed when programming a recipient’s cochlear implant after surgery. It is important to recognize that over time, objectives and procedures for device programming may change as the recipient gains more experience with their cochlear implant and adapts to electrical stimulation.

15. Understood, but can you hit some of the highlights?

Sure. First, the programming section establishes the differing goals for initial activation and subsequent programming appointments. The objective of initial activation is to provide for stimulation that is audible yet comfortable to allow for early acceptance of the device. In contrast, during subsequent programming, the goal becomes more specific and the clinician should seek to establish an electrical dynamic range that provides a broad spectrum, a wide enough electrical dynamic range to allow for perception of soft, moderate, and loud sounds.

Here is a summary of some more specific recommendations from the guideline:

- Measure impedances.

- Select the processing/coding strategy prior to obtaining information used to establish the electrical dynamic range.

- Establish the electrical dynamic range on selected electrodes using both psychophysical and objective measures.

- When using psychophysical measures, it is important to recognize that obtaining accurate psychophysical measures of loudness and pitch is likely to improve recipient performance with the cochlear implant. As such, T-levels should be established using similar procedures to those used when performing threshold audiometry. Upper stimulation (C/M) levels should be set in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommended loudness level, noting that underestimating upper stimulation levels may negatively impact speech recognition, sound quality and the ability to monitor the sound of one’s voice, and that overestimating upper stimulation levels may result in discomfort and aversion to the device, and negatively impact speech recognition and sound quality.

- Both prelingually deafened adults and young children may demonstrate a limited ability to provide reliable behavioral feedback necessary to establish the electrical dynamic range. Therefore, programming may need to rely more heavily on objective measures to ensure proper device function and appropriate sound-processor settings. Common objective measures include ESRT measures and ECAP measures. Several studies have shown strong correlations between ESRT and map C/M levels. As a result, ESRTs can be helpful for setting upper-comfort levels for prelingually deafened children, who often lack the concept of “loud” and may be less likely to demonstrate adverse reactions to loud sounds, as well as for adults who provide inconsistent reports of loudness. In contrast to ESRT, ECAP thresholds generally occur within the electrical dynamic range, although they may exceed upper comfort levels for some recipients. ECAP thresholds almost always occur above behavioral T level. ECAP thresholds, therefore, represent a level that should be audible to the recipient.

- Optimization of programming through loudness balancing and pitch scaling.

- Ensure comfort of sound loudness and quality as well as audibility through “live voice” stimulation.

- Counseling, of some form, should occur at all cochlear implant appointments.

16. How does the guideline account for the differences among cochlear implant devices?

This is a really interesting question. It touches on one of the main goals of the group who worked to create this practice guidelines document. One of our main goals was to create a document that was not manufacturer specific. We wanted a document that took cochlear implant clinical practice outside of the context of “this manufacturer says to program this way” or “that manufacturer says to program that way”. Our goal was to describe a set of practices that transcends manufacturer-specific information. We wanted a document that provided the clinical practice recommendations for cochlear implants, not the manufacturer recommendations for cochlear implants.

17. Were there any sections that required a lot of discussion to determine recommendations?

All of the sections prompted extensive discussion! These discussions revolved around what specific recommendations to make, the organization of the recommendations, and determining the objective of each section. For example, the billing section, which in the final document is a single statement, underwent hours of discussion across multiple task force meetings. In the end, the task force agreed upon the single statement due to the changing nature of billing.

18. What gaps in the background research were identified?

Those recommendations where no evidence was found are noted in the guideline as “No published evidence available. Current clinical practice.” Surprisingly, there were very few areas where no research was identified and the majority of those recommendations were very logical. This doesn’t mean that continued research isn’t needed across all areas, though. As I mentioned earlier, there were several recommendations that were supported by lower level research or by only limited published evidence. Further, cochlear implant technology will continue to advance, which will lead to changes in clinical practice and outcomes.

19. Any unexpected or controversial recommendations in the guidelines document?

I don’t believe there are any new or unexpected practice recommendations, but I think the guidelines may present a new way of thinking about components of care for individuals who use cochlear implants, at least for some practicing clinicians.

20. It must have required quite a team effort to accomplish this project! Who was involved?

It certainly did. The members of the 2015 Task Force included: Holly Teagle (Co-Chair); William Shapiro (Co-Chair); Anne Beiter; Laurie Eisenberg; Jill Firszt; Michelle Hughes; Geoff Plant; Amy Robbins; Tom Walsh; and Terry Zwolan. I served as Chair of the 2017 Task Force whose members included: Lavin Entwisle; Sarah Warren, and Michael Scott. The guidelines can be accessed here: https://www.audiology.org/sites/default/files/publications/resources/CochlearImplantPracticeGuidelines.pdf

References

American Academy of Audiology (2013). Pediatric amplification practice guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.audiology.org/sites/default/files/publications/PediatricAmplificationGuidelines.pdf

Cox, R. (2005). Evidence-based practice in provision of amplification. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 16(7), 419-438.

Kredo, T., Bernhardsson, S., Machingaidze, S., Young, T., Louw, Q., Ochodo, E., & Grimmer, K. (2016). Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 28(1), 122-128.

National Institutes of Health. (2017). Clinical practice guidelines. Retrieved from https://nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/clinicalpractice.htm

Treweek, S., Oxman, A.D., Alderson, P., Bossuyt, P.M., Brandt, L., Brozek, J.,...Alonso-Coello, P. (2013). Developing and evaluating communication strategies to support informed decisions and practice based on evidence (DECIDE): protocol and preliminary results. Implement Science, 8(6). doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-

Citation

Messersmith, J.J. (2019). 20Q: An overview of the new cochlear implant practice guidelines. AudiologyOnline, Article 25212. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com