From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

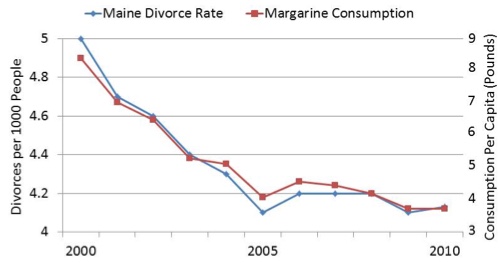

In recent years, it has become trendy for audiologists to purchase summer homes in the state of Maine. The relationship depicted in the chart below may be of interest to any of you who have, or are considering, a home in the Pine Tree State.

The data in the chart are real and what you see is correct. There is an association, and a very strong correlation (>.90), between the consumption of margarine and the divorce rate in the state of Maine. While these data are just from the first 10 years of this century, we have every reason to believe that the trend is continuing. Great news for the dairy industry’s “Back-to-Butter” campaign! All rather absurd? Yes, but it clearly reminds us that you can have relationships, associations, very strong correlations, and even casual links . . . without causation. Which takes us to this month’s 20Q topic: hearing loss and dementia.

You’ve probably noticed that there has been a lot of talk about dementia in recent years, and more and more news items related to dementia and hearing loss. Many audiologists have picked up on this, especially the notion that hearing aid use might delay, or even prevent, dementia. There is even a new training program designed for licensed audiologists and hearing instrument specialists from the American Brain Council, where you can become a “Certified Dementia Prevention Specialist.”

We do know that the use of hearing aids increases activity, communication and socialization, which can be related to cognition, which often is related to dementia. So is all this just an association, or is there a causal link? This is important stuff, and we really need reasoned thinking. And we have just the person to do that—this month’s 20Q guest author.

Piers Dawes is a senior lecturer in audiology at the University of Manchester. He is a developmental neuropsychologist with a PhD in experimental psychology from the University of Oxford. You are probably familiar with his many publications related to the epidemiology of hearing loss, dementia, hearing genetics, treatments for hearing loss including hearing aid uptake and hearing aid benefit, and the impact of hearing impairment on development and quality of life. He was a 2013-2014 US-UK Fulbright scholar, and was awarded the British Society of Audiology's Thomas Simm Littler Prize in 2014 for work on the epidemiology of hearing loss and acclimatization to hearing aids.

Piers is ideally suited to address this month’s 20Q topic, as he is the founding chair of the British Society of Audiology's special interest group for cognition in hearing. He also is the co-lead of ‘Ears, Eyes and Mind: The ‘SENSE-Cog Project’ to improve mental well-being for elderly Europeans with sensory impairment’, a European Commission-funded Horizon 2020 project.

Given that Piers is from the UK, he may not have the latest data on margarine consumption and Maine divorces, but he is an expert on associations and links, and how they relate to hearing loss and dementia. You’ll enjoy his thought-out explanation in this installment of 20Q.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

January 2017

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Hearing Loss and Dementia—Association, Link or Causation?

Learning Outcomes

- Readers will be able to define dementia and explain why there is a renewed research and public interest in dementia.

- Readers will be able to discuss the relationship between hearing loss, cognition, and dementia.

- Readers will be able to describe findings from key published research in the area of hearing loss and dementia, and discuss research projects underway in this area.

Piers Dawes

1. I think I pretty much know what dementia is, but what is your definition?

‘Dementia’ describes a set of symptoms that include memory problems, language problems, personality changes or thinking difficulties. More than one hundred types of dementia have been identified. The most common type is Alzheimer’s dementia. The cause of dementia is damage to the brain due to disease (in the case of Alzheimer’s dementia) or a series of strokes (in the case of vascular dementia). Dementia is a progressive degenerative disease, which means that a person with dementia has more and more difficulty with memory, understanding and communication over time.

2. Why does there seem to be a surge of interest in dementia, both in the general community and the audiology community in particular?

Populations are aging. Due to changes in birth rates and increased longevity, there are growing numbers of older people and proportionally fewer young people. Aging populations mean increasing numbers of people with age-associated conditions like dementia. In developed countries, the number of people with dementia will increase 100% by 2040 as compared with 2001 levels (Ferri et al., 2005). Increases of up to approximately 400% are projected in low and middle income countries. There will be many more individuals, family members and friends who suffer the impacts of dementia. There are financial costs, too. Dementia care is expensive, so we will collectively need to bear increased costs of care for people with dementia. The international dementia challenge is to identify treatments and management strategies to prevent or delay the onset of dementia and to improve quality of life for people with dementia. Effective treatment and management of hearing problems may have a role in addressing both of these priorities.

3. Those are alarming statistics. And hearing impairment is linked to dementia, right?

You use the word “linked,” and that is possibly true, but we have to be careful regarding what word we use here. There is evidence that people with poorer hearing tend to have poorer cognition function. Hearing impairment is associated with increased risk of developing dementia, and there is very high comorbidity of hearing impairment and dementia.

4. Is this evidence that hearing impairment causes dementia?

No. All of the studies that show poorer hearing is associated with poorer cognition function, and that hearing impairment is associated with increased risk of dementia, are correlational. It is not possible to establish the direction of causation, or even if there is a direct causal link between hearing impairment and dementia from correlational studies.

It might be that hearing impairment contributes causally to risk of dementia. But there are at least three possibilities that could account for the association between poor hearing and poor cognition/dementia: 1) hearing loss impacts cognition; 2) cognition impacts hearing; or, 3) a shared factor impacts both hearing and cognition.

5. I see. So tell me first how hearing loss may impact cognition.

Let's explore the possibility that hearing impairment does have a direct causal impact on cognition. There are several ways that hearing impairment may have a direct causal adverse impact on cognition. First, the impact of hearing impairment might be because hearing impairment increases listening effort, which means that people have fewer cognitive resources available for doing other things. Devoting cognitive resources to listening may therefore manifest as an apparent reduction in cognition, even though the underlying cognitive system is fine. One problem with this explanation is that the association between hearing impairment and cognition remains even when cognition is measured with visually-based tasks that do not require listening.

Another possible impact of hearing on cognition is that a chronic state of effortful listening results in permanent neuroplastic changes that adversely impact on cognition. This idea is based on imaging studies that show that hearing impairment is correlated with reductions in brain volume. However, the association between hearing impairment and reduced brain volume would also be consistent with a common cause explanation. It’s an interesting idea that listening effort could cause cognitive decline, but I don’t find it very plausible. Doing cognitively taxing things is associated with preserved cognition rather than with cognitive decline. That is why people do Sudoku, crosswords, brain training programs and generally keep up cognitively stimulating activities in retirement in an effort to stave off cognitive decline. Also, there are numerous listening training programs aimed at improving benefit from hearing aids or cochlear implants, or as an alternative intervention to amplification. These training programs involve training with taxing listening conditions for extended periods. As far as I know, none of these programs has ever reported declines in cognition as an adverse side effect.

Finally, the impact of hearing on cognition may be indirect. For example, hearing loss may lead to social isolation, depression and/or reduced self-efficacy (Dawes, Emsley et al., 2015). All of these things are linked to reduced cognitive performance and increased risk of dementia.

6. Okay. Then let’s look it the other way around - how might cognition impact hearing ability?

There is good evidence to say that listening is cognitively taxing, especially in complex listening environments. For example, one must use one’s attention to selectively attend to the signal of interest, and keep updating and making links to relevant information in memory during listening. Reduced cognitive ability would therefore result in poorer listening performance.

Hearing tests are cognitively taxing. Especially cognitively demanding tests like dichotic listening tests of auditory processing, and even apparently simple tasks like pure tone audiometry, make substantial demands on cognitive abilities.

Therefore, someone may do poorly on a hearing test at least partly because they have poor cognition rather than poor hearing. Confounding with cognitive factors on hearing tests is a problem for researchers who wish to dis-entangle cognitive factors from hearing factors, and for clinicians (psychiatrists/neurologists and audiologists) who wish to differentially diagnose hearing and cognitive impairments. One solution to avoid confound with cognition on hearing tests might be to use objective measures of hearing, such as electrophysiological ones.

7. Any other explanation?

There is one. The final possibility is that rather than hearing and cognition being causally linked to each other, hearing and cognition are associated because they share a common causal factor. Actually, it would be more accurate to say ‘factors’ rather than factor. Both hearing loss and cognitive decline/dementia are complex, multi-factorial conditions. Both conditions share causal correlates such as age-associated chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, hormonal changes, and cardiovascular changes. Hearing loss and cognitive decline also share some genetic susceptibility factors and environmental/lifestyle risks. For example, aerobic exercise, low fat Mediterranean diet, non-smoking and moderate alcohol consumption are linked to both preserved cognition and preserved hearing.

8. So if I have this right - hearing impacts cognition, cognition impacts hearing, and common factors influence both hearing and cognition! Which one actually explains the link between hearing and dementia?

All these possibilities are not mutually exclusive, and it is likely that all three are true to some extent.

9. I know that some audiologists have been pointing to the link between hearing impairment and dementia to encourage people to get help for hearing impairment. What are your thoughts on this?

I think that we need to be careful about the assertions that we make in this area, whether it’s related to funding of services or the sale of hearing aids. There is currently no convincing evidence to show a causal link between hearing loss and dementia or the impact of treating hearing impairment in preventing dementia. There may be unintended consequences of asserting that there is a strong causal link and that treating hearing impairment reduces risk of dementia.

10. What do you mean by ‘unintended consequences’?

Evidence from health psychology in relation to a range of health issues suggests that scary messages like ‘smoking causes cancer’ or ‘hearing impairment causes dementia’ (as well as scaring people unnecessarily) may have the unintended consequence of encouraging denial or dismissal, making people less likely to quit smoking or seek help for hearing problems. Effective health promotion messages are ones that are positively framed. For example ‘quitting smoking improves physical fitness’. If we want to encourage people to do something about hearing problems, we should emphasize the positive benefits for which there is good evidence. For example, that hearing aids are effective in improving communication and quality of life.

11. That makes sense. You also mentioned something about justifying funding of hearing services?

In the UK, I’ve observed numerous instances where a supposed causal link between hearing loss and dementia and the benefit of hearing aids in preventing dementia has been cited in relation to arguments in favor of socially supported hearing health care by the National Health Service.

I worry that asserting that hearing aids reduce risk of dementia risks discrediting the whole argument for providing socially supported hearing health services.

It is unwise to argue that hearing aids reduce risk of dementia with experts who are well versed in evidence-based medicine and who are aware that there is currently no convincing evidence that hearing aids reduce risk of dementia. Making one clearly unsubstantiated argument may make it easier for health service providers to ignore other valid arguments for provision of hearing services that do have a good level of supporting evidence.

The argument that we should do something about hearing impairment because hearing impairment causes dementia misses the important point that hearing impairment itself has very significant impacts. Hearing impairment deserves attention in its own right, rather than appealing to a possible impact on a second condition.

I think we should certainly argue for the importance of identifying and treating hearing impairment, particularly in the context of cognitive impairment and living well in older age. But I think that we should consider the approach we take, and that a more nuanced and well considered argument would be desirable.

12. If hearing loss does lead to cognitive decline and dementia, could there be potential to reduce cognitive decline by treating hearing impairment?

If treating hearing impairment by fitting hearing aids (or by other means) is effective in reducing the adverse impact of hearing impairment on cognition (for example by reducing depression or promoting social engagement or self-efficacy as found in Dawes, Emsley et al., 2015), than one might expect to see a positive impact of treatment of hearing impairment on cognitive decline and risk of dementia.

There are a handful of studies that have examined the impact of hearing aid provision on cognitive outcomes, as described in a nice review paper by Kalluri and Humes (2012). But, findings of these studies include an entirely mixed set of results: no difference, better cognition and poorer cognition among hearing aid users compared to non-users! Perhaps a bigger problem with these studies is that all of them looked at cognitive outcomes over rather short periods of time of up to 1 year or so. Cognitive decline is very gradual, and one needs study durations of several years to observe age-related declines in cognition. It is not feasible to observe any impact of hearing aid use on cognitive decline in short duration studies.

13. So, what you would need is a long-term intervention study?

Yes. Ideally, one would do a randomized controlled trial of hearing aid use, with cognitive outcomes measured over long durations of at least five years or so, to be able to observe an impact on cognitive decline. There are substantial practical, scientific, financial and ethical problems with such a study. Scientific and practical problems include selective drop out and practice effects that bias results. A properly-designed intervention study would need to be large, and consequently would be very expensive, and results would not be available for at least five years. There are ethical problems with an intervention study, too. Because the benefits of hearing aids in reducing hearing disability are clear, it would be unethical to deny hearing aids to a control group of people who have clinically significant hearing impairment, while providing hearing intervention to the intervention group – especially for the long time duration that would be required for the study.

14. Sounds like intervention studies can be problematic in practice, but what is the alternative?

One possibility is to examine cognitive outcomes associated with hearing aid use in observational studies that have data on hearing, cognition and hearing aid use.

15. That sounds ideal! What’s the catch?

The problem with these sorts of studies is that they are observational. Only a minority of people with hearing impairment use hearing aids, and there are important differences (for example in socio-economic status, education level and ethnic background) between hearing aid users and non-users. These differences are linked to health outcomes including cognitive decline and dementia. Researchers try to control for these differences by measuring them and adjusting for them statistically. The problem remains that if one does observe a difference in cognitive (or any other) outcome between hearing aid users and non-users, there is a possibility that the difference is due to uncontrolled or insufficiently controlled confounders, rather than hearing aid use.

16. Okay, I get your point. Given that caveat, do we have good data from observational studies?

I am aware of four studies to date that have modelled the impact of hearing aid use on cognitive outcomes over durations longer than three years. Findings are mixed.

Our recent study showed no impact of hearing aid use on cognitive decline or incident dementia over 15 years of follow-up of 666 adults with hearing impairment (Dawes, Cruickshanks et al., 2015). Another study that we are currently preparing for publication used data from the large UK Biobank study with just under 5,000 people with hearing impairment. In this study, there was no impact of hearing aid use on cognitive decline measured over 4-7 years. A small US study (Deal et al., 2015) showed a positive impact of hearing aid use on one of three cognitive tests over 20 years of follow-up. A recent French study reported 25 years of follow-up using mini-mental state exam scores and self-reported hearing problems to categorize people as hearing impaired (Amieva et al., 2015). Unfortunately, this study did not directly compare cognitive decline in hearing aid users versus non-users or report the characteristics of hearing aid users versus non-users, so it is difficult to make any conclusion about the impact of hearing aid use on cognitive decline from this study.

We clearly need more studies to model the impact of hearing aid use in other populations. The evidence so far does not support a robust, clinically-important effect of hearing aids in reducing cognitive decline.

17. That is rather disappointing! What role is there for interventions for hearing impairment in relation to cognitive decline and dementia?

Perhaps one thing to note is that the benefit of hearing aids in reducing cognitive decline does not necessarily need to be clinically significant (i.e., that there is a large beneficial effect of managing hearing impairment on cognitive decline/dementia at the level of the individual). Because hearing impairment is so highly prevalent, if small gains in reducing cognitive decline were achievable in a substantial proportion of the general population by treating hearing impairment, that could translate to a substantial reduction in numbers of people with dementia.

At present, the jury is out on whether hearing aids or any other type of intervention for hearing impairment has much impact on cognitive decline. Based on the evidence to date, I suspect that the benefit of hearing aid use on cognitive decline is likely to be marginal, if any. However, I think there are likely to be very valuable impacts of treating hearing impairment both in terms of preventing the onset of dementia, dementia management and improving quality of life for people with dementia.

18. Wait - aren’t you contradicting yourself? How can it be that there might not be a substantial effect of hearing aid use or other types of intervention on cognitive decline, but there might be a valuable impact in preventing dementia?

An important thing to understand is that diagnosis of dementia is based not only on evidence of cognitive decline, but also evidence of sufficient functional impairment such that a person struggles to cope in everyday life. Hearing impairment causes functional impairment, and hearing impairment may have a particularly severe impact in the case of someone with impaired cognition. If one could remediate the excess disability due to hearing impairment (by providing hearing aids or other hearing intervention), one could improve functional ability and delay or prevent progression to ‘dementia’. In other words, a person may have cognitive impairment, but if they have functionally adequate hearing they may be able to compensate well and not fit a diagnosis of ‘dementia’. Hearing aids (or other intervention for hearing impairment) might not have a substantial impact on trajectories of cognitive decline. But there is very good evidence that hearing aids are effective in reducing disability.

For people with dementia, treating hearing impairment could reduce the apparent severity of dementia. There is evidence that hearing aids reduce the psychological and behavioral symptoms of dementia (including hallucinations, aggression, anxiety and apathy), promote orientation and reduce the burden on family and friends for people with hearing impairment and dementia. Because hearing interventions are relatively inexpensive, there may be substantial health economic benefits of treating hearing impairment in reducing the cost of dementia care.

19. Those are exciting possibilities. Where do we go from here?

I think that we need to try to understand the interactions of hearing impairment as well as the benefits of treating hearing impairment within the overall context of aging. This approach would involve taking into account other sensory impairments (especially visual impairment), as well as physical, psychological and contextual environmental changes with age. I think that we need to focus on the functional benefits of hearing aids in reducing disability (particularly in the context of cognitive impairment), on quality of life, on caregiver burden, and on service use and incidence of dementia.

In order to influence policy, we also need high quality health economic data to demonstrate the financial benefits of effective identification and management of hearing impairment. We also need to ensure that audiologists have the appropriate training and support to provide the best quality care for people with dementia.

20. What is currently happening to address these issues?

This is a hot topic area, and I am aware of excellent research and clinical service development happening all around the world. I'll give you a few examples.

Some notable research projects include our own SENSE-Cog study, which is a five year Horizon 2020 project funded by the European Commission to address hearing and vision impairment in relation to mental well-being in older adults in Europe. SENSE-Cog involves 17 major clinical and research partners across Europe. It addresses questions relating to the impact and interactions of sensory and cognitive impairment using epidemiological methods, and includes developing novel assessments, and evaluating interventions, health economics and patient involvement. SENSE-Cog is led by my colleague Dr. Iracema Leroi, an academic psychiatrist here in Manchester UK, and myself. Dr. Frank Lin’s group at Johns Hopkins in the US does a lot of excellent work, and at the time of this article had just submitted a funding application to examine the impact of treating hearing impairment on cognitive decline. The Canadian Consortium for Neurodegeneration in Aging, a large multi-disciplinary study, includes a dedicated research team led by Dr. Natalie Phillips focusing on ‘Interventions at the Sensory and Cognitive Interface’.

In terms of clinical service development, the British Society of Audiology (BSA) special interest group for cognition and hearing (which I chair) is currently developing evidence-based clinical guidelines for assessment and management of hearing impairment in people with dementia (led by Dr. Sarah Bent). These guidelines will be freely available from the BSA website beginning in summer 2017.

This is an exciting time for research and clinical developments that promise to lead to real solutions for tackling the dementia challenge and improving quality of life for older adults.

References

Amieva, H., Ouvrard, C., Guilioli, C., Meillon, C., Rullier, L., & Dartigues, J. (2015). Self-reported hearing loss, hearing aids, and cognitive decline in elderly adults: A 25 year study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(2), 2099-2104.

Dawes, P., Cruickshanks, K., Fischer, C., Klein, B., Klein, R., & Nondahl, D.M. (2015). Hearing aid use and long-term health outcomes: hearing handicap, mental health, social engagement, cognitive function, physical health and mortality. International Journal of Audiology, e-pub ahead of print. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1059503

Dawes, P., Emsley, R., Moore, D., Cruickshanks, K.J., Fortnum, H., Edmondson-Jones, M., . . . Munro, K. (2015). Hearing loss and cognition: the role of hearing aids, social isolation and depression. PLOS One. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119616

Deal, J.A., Sharrett, A.R., Albert, M.S., Coresh, J., Mosley, T.H., Knopman, D., . . . Lin, F.R. (2015). Hearing mpairment and cognitive decline: A pilot study conducted within the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 181(9), 680-90. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu333

Ferri, C.P., Prince, M., Brayne, C., Brodaty, H., Fratiglioni, L., Ganguli, M., . . . Jorm, A. (2005). Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet, 366(9503), 2112-2117.

Kalluri, S., & Humes, L.E. (2012). Hearing technology and cognition. American Journal of Audiology, 21(2), 338-343.

Citation

Dawes, P. (2017, January). 20Q: Hearing loss and dementia - Association, link or causation? AudiologyOnline, Article 19111. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com