From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

Happy 2016 from 20Q! It’s only January, but some of us already are looking forward to spring (especially those of us who live in North Dakota). And there is some good news on that front—baseball’s spring training opens in just five weeks! One of baseball’s legends, however, won’t be around to witness the opening this year. Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra died last September at the age of 90.

Gus Mueller

Yogi Berra was an all-star catcher with the great New York Yankee teams of the 1950s and early 1960s, and certainly, one of the top catchers of all time. He is known as one of the game’s greatest clutch hitters, played on 10 world championship teams, and was named the league’s MVP on three occasions.

Yogi was a huge fan-favorite, and also a favorite target for New York reporters. He soon became known for his malapropisms and paradoxical quotes. The popularity and use of these quotes has spread outside of baseball, and today they are referred to as Yogi-isms (or Yogisms). In honor of Yogi, our title for this month’s 20Q is one of them: "The future ain’t what it used to be."

In case you’re wondering, all of this does have something to do with audiology. Back in May of 1994, I wrote an article titled, Update On Programmable Hearing Aids (With An Assist From Yogi Berra). At the time, there were a lot of questions surrounding the use of programmable hearing aids, and I thought it might be appropriate to use several Yogi-isms to help sort out the confusion. With the passing of Yogi, it only seems appropriate to revisit that theme today to look at current issues regarding hearing aid selection and fitting. In a way, it's like "déjà vu all over again."

With so many Yogi-isms to use, I invited some colleagues to contribute. This is a very special group. Not only are they all experts, with a fondness for baseball, but they also all are editors (or previous editors) of audiology journals. Here is this month's All-Star 20Q lineup:

- David Fabry: Editor-In-Chief, American Academy of Audiology; Editor of Audiology Today since 2008; previous editor of American Journal of Audiology.

- David Kirkwood: Recently retired Editor-In-Chief of Hearing Health & Technology Matters; previously Editor-in-Chief of The Hearing Journal for 20 years.

- Karl Strom: Editor-in-Chief at The Hearing Review & Hearing Review Products for past 23 years.

- Carolyn Smaka: Editor-in-Chief, AudiologyOnline.

- Brian Taylor: Editor of Audiology Practices, the journal of the Academy of Doctors of Audiology; Editor, Hearing News Watch for Hearing Health & Technology Matters.

Each contributor has selected a Yogi-ism to illustrate and discuss a particular area of hearing aid selection and fitting. Given our baseball theme, we included a bonus section with personal baseball vignettes from the authors. In a real baseball lineup, I never quite had the speed to bat first, but I’ll take the leadoff position for this venture.

Contributing Editor

January 2016

To browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles, please visit www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Hearing Aids - The Future Ain't What It Used to Be!

Learning Objectives

- Readers will be able to define efficacy and effectiveness in regard to hearing aid research, and describe studies that examined each.

- Readers will be able to explain how hearing care professionals can help ensure successful outcomes with hearing aids, in addition to following evidenced-based practices.

- Readers will be able to list two pre-fitting tests and explain how they may support a successful hearing aid fitting.

- Readers will be able to define social marketing, and an SEO-focused marketing approach for a hearing care practice.

"You Can Observe a lot By Watching"

Gus Mueller: Today in baseball, we have something called sabermetrics, the empirical analysis of the many skills related to playing baseball. This term comes from the acronym SABR, which stands for the Society for American Baseball Research. But high sabermetric performance doesn’t always equate to the player you want on your team. There could be reduced performance under stress, poor clubhouse chemistry, or off-field distractions that play into the overall evaluation. So, as Yogi said, “you can observe a lot by watching.”

As we select the best amplification products and features for specific patients, we too can learn a lot by watching. Sure, we may rely somewhat on the empirical “stats” provided by the manufacturer, but we also need to consider what the performance will be in real-world situations. In essence, what I’m referring to is efficacy versus effectiveness. Here is a brief definition of how these two terms are typically used regarding hearing aid research:

- Efficacy: Does the treatment (e.g., hearing aid feature or algorithm) work as it was designed to work, under ideal controlled circumstances?

- Effectiveness: Does the treatment (e.g., hearing aid feature or algorithm) work as it was designed to work under ordinary real-world situations?

It has long been popular to use speech recognition testing in an audiometric test booth to prove the superiority of a product or a hearing aid feature. I’m not sure exactly when this practice started, but I personally recall a 1972 monthly installment of the Maico Audiological Library Series devoted to promoting the new Maico directional hearing aid. This efficacy study showed that at an SNR of -6 dB, group speech recognition was 24% better for the directional hearing aid (Lentz, 1972). Although this example is from over 40 years ago, it’s not all that different than the supporting research we often see today. What we want to “observe by watching,” however, is the real-world effectiveness of these products and algorithms, so let’s look at a few examples.

Validation of the NAL-NL1 fitting algorithm. My favorite research designs are the ones that have both a laboratory and a real-world component. An example of this is one by Robyn Cox and colleagues (2012), assessing the NAL-NL1 prescriptive fitting method for two groups of individuals with high frequency hearing loss; the participants in one group all had high frequency cochlear dead regions. The NAL-NL1 prescription was compared to a fitting that rolled off gain for the high frequencies, similar to most manufacturers’ proprietary fittings. The laboratory data showed improved speech recognition for the NAL program over the “roll-off-highs” program for both groups (although somewhat less in noise). In the real-world listening environments, subjects from both groups also tended to give higher ratings to their speech understanding when they listened using the NAL program. All is right in the world.

Adaptive directional technology. Not all research regarding hearing aid processing, however, has the laboratory-to-real-world agreement of the Cox et al. (2012) study. Remember when "adaptive directional" was a highly promoted feature? In laboratory testing, Ricketts, Hornsby, & Johnson (2005) found a 2 dB SNR advantage for the adaptive versus the fixed directional settings for both a fixed and a moving sound source, and the fixed and adaptive both showed a large SNR advantage over omnidirectional (6 dB and 8 dB respectively). Impressive findings. But on the other hand, in a different study using the same model hearing aids involving a real-world questionnaire, Palmer et al. (2006) found that only about 1/3 of the subjects preferred the directional setting over omnidirectional, and for the group that did, there was no significant preference difference for adaptive over fixed.

Directional benefit for older v. younger people. A study that had laboratory vs. real-world data that were somewhat of a head scratcher was published by Yu-Hsiang Wu (2010). He examined directional benefit for older versus younger individuals. In the laboratory, both younger and older individuals showed a large benefit for directional processing based on their HINT performance (~4.5 dB). But in real-world field testing, preferences for directional processing only were present for the younger subjects. Wu suggests that this could be due to age-related social and/or cognitive changes for the older group. If we look at the individual data for Wu’s participants, we see that the substantial drop-off for real-world benefit begins at age 60. Age 60? Most of us do not think of 60-year-olds as having significant social or cognitive changes. But, maybe we should? And if so, should this finding then alter our counseling to the large majority of our patients fitted with directional technology, who are over the age of 60?

When we are doing our observing and watching, we also have to consider statistical significance versus clinical (real-world) significance. Many studies evaluating directional technology and noise reduction use an SNR test such as the HINT. With this type of measure, if the sample size is at least 15-20 participants, it’s common that differences of 1.5-2.0 dB are statistically significant. But what does this really mean for your patient? If a new DNR system results in a 2 dB SNR improvement, will this be perceptually noticeable for your patients? Probably not. Recent research from McShefferty and colleagues (2015) reported that a just-noticeable-difference for a speech-to-noise ratio is about 3 dB.

Another example of how statistical significance can be somewhat misleading relates to recent research involving cognitive processing. In one of the most frequently cited hearing aid articles in recent years, Sarampalis et al. (2009) reported that at a difficult SNR in a dual-paradigm task, the visual reaction time for a group of subjects was significantly better with noise reduction “on” compared to “off”. This is a great story to tell our patients when they ask about the proven benefit of digital noise reduction, right? But, while significant, the mean reaction time with DNR “on” was only 0.05 seconds—1/20 of a second. How does this relate to the real world? Yogi Berra was darn good at hitting a major league fastball. The visual reaction time required to hit a slightly-below-average 85-mph fastball is 0.49 seconds. But some pitchers throw a 95-mph fastball, which requires a visual reaction time of 0.44 seconds. So yes, for hitting a major league fastball, 0.05 seconds matter. This reaction time improvement probably also matters if you’re an Indy car driver traveling at 230 mph. But for your average patient—maybe not so much.

I hope Yogi’s aphorism was right, and “the future ain’t like it used to be.” In the future, I'd like to see a greater emphasis on hearing aid research with a real-world effectiveness focus, and less reliance on laboratory efficacy data. This will help us determine what features and algorithms truly provide patient benefit, improve our counseling, and when “we observe a lot by watching”, we just might see enhanced patient satisfaction.

"It Ain't Over ‘Til It’s Over"

Brian Taylor: Hearing aid selection and fitting, and the counseling associated with the process, are challenging tasks. There are, of course, several factors that must be carefully considered, but research indicates clinicians typically utilize just a few pre-tests prior to hearing aid fitting: pure tone testing, speech recognition in quiet and an evaluation of patient lifestyle (Gioia et al., 2015). Coincidentally, these are probably the same core pre-fitting tests clinicians used in Yogi Berra’s prime – the 1950s.

Oftentimes, however, there is considerable information that could have been gathered during the pre-fitting appointment, and then used effectively during the hearing aid selection, fitting and counseling process. After all, “it ain’t over” until we have optimized patient satisfaction during real-world hearing aid use.

The point of this Yogi-ism, therefore, is that when properly implemented testing is conducted prior to the fitting, the findings from this testing can continue to be used until the hearing aid fitting and follow-up appointments are over. Let’s review pre-tests that could be conducted prior to selecting hearing aids. From top to bottom it’s a veritable Murderers’ Row, including:

- Pure-tone thresholds

- Speech understanding in quiet

- Speech understanding in noise

- Identifying listening priorities & self-reported difficulties in everyday communication

- Loudness discomfort levels

- Acceptance of background noise

- Cognitive function

- Expectations

- Motivation

This all-star line-up of pre-tests ensures the fitting and selection process is individualized to the patient. After all, if you don’t know where you’re going, you are likely to wind up someplace else. Given the presence of computer-based audiometry and short, standardized screening materials, there is really no reason all nine cannot be completed with most all new patients.

Items one and two in the line-up – pure-tone threshold testing and speech understanding in quiet – are like the first two hitters in the batting order. Their job is not flashy; they just have to be reliable and consistent. Likewise, the bottom five items in the line-up are part of a platoon system. On some days you might rely on one more than the others, depending on the situation. Like all great teams, everyone has to contribute.

Table 1 shows some of the specific tools you can add to your own line-up.

| 5. Loudness Discomfort Level (LDL | Loudness Contour Testing |

| 6. Acceptance of Background Noise | ANL using the uHear app |

| 7. Cognitive Function | MMSE, MoCA, CIT-6 |

| 8. Expectations | ECHO |

| 9. Motivation | COAT |

Table 1. Pre-fitting test topics and their associated metrics.

We are left with the heavy hitters, expected to be at the star performers for an entire 162 game season. The heart of the pre-fitting test line-up is speech understanding in noise and identifying the listening priorities and difficulties of the patient. The tools I’m recommending to accomplish these two different tasks are the QuickSIN (Killion, Niquette, Gudmundsen, Revit, & Banerjee, 2004) and the COSI (Dillon, James, & Ginis, 1997). There are many speech-in-noise tests used clinically, but the QuickSIN is the most popular. For speech-in-noise testing, however, the BKB-SIN (Bench, Kowal, & Bamford, 1979) or the WIN (Wilson, 2003) certainly could be substituted with equal success.

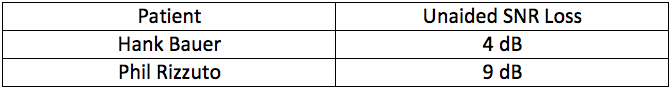

The results of the QuickSIN are an invaluable tool for counseling, and in some cases, the results also can be used for determining hearing aid accessories. For example, in Table 1 are QuickSIN results for two fictitious patients, who we’ll call Hank Bauer and Phil Rizzuto. Both have the same general degree of hearing loss and LDLs, and they also had the same speech recognition in quiet. According to the QuickSIN results, however, Phil needs a more favorable signal-to-noise ratio to perform in background noise when compared to Hank. Phil certainly is a candidate for some type of wireless companion microphone: A necessary feature, if you want to improve Phil’s SNR more than 3-4 dB (Thibodeau, 2014). With the right features and fitting skill, it is possible Phil will outperform Hank in noisy places. But, what if Hank, with his milder SNR loss, happened to have demanding listening needs, and Phil with his moderate to severe SNR loss, spent virtually all of his time in quiet, housebound activities? Your recommendations might change. Knowing the patient’s listening demands, which are listed and self-rated on the COSI, combined with knowledge of the patient’s SNR loss, can change, rather dramatically, how you counsel both Phil and Hank.

Table 2. The unaided Quick SIN scores (SNR-Loss) for two fictitious patients.

By sticking with a consistent line-up of pre-tests and relying on your heavy hitters - QuickSIN and COSI - you can come through in the clutch for your patients. Recognizing that it’s not over ‘till it’s over, and utilizing a wider range of pre-test findings during the counseling process, is a grand slam.

"Nobody Goes There Anymore - It's Too Crowded"

David Kirkwood: Yogi and I go way back. At age 5, I discovered baseball, started cheering for the New York Yankees, and quickly picked the team’s funny-looking catcher as my favorite player.

I selected a Yogi-ism that I believe has particular resonance for audiologists. When asked by a reporter why he had quit going to Rigazzi's, a popular restaurant in his hometown of St. Louis, Yogi explained, "Nobody goes there anymore. It's too crowded." While that’s a bit of an oxymoron, it’s not hard to see what he meant. We’ve probably all had a favorite place where we liked to go with friends. But then too many other people discovered it, it became crowded, and it just wasn’t the same. As a result, nobody (at least nobody that we knew) went there any more.

So what does that have to do with the practice of audiology? The hearing care field is driven by continual innovation. To remain competitive, every major hearing aid manufacturer must unveil some important new breakthrough in technology at least once a year. Of course, any experienced audiologist or hearing aid specialist realizes that very few of these innovations, no matter how much they are hyped, are really going to revolutionize the hearing aid as we know it. Still, practitioners feel under constant pressure to stay on top of new technology, to become one of those “early adopters”, and promote these new features to their patients.

That’s a good attitude, within reason. Progress in hearing care depends on there being practitioners who are eager to try new technology and see how it works on their patients. However, it’s also important that professionals not focus so much on discovering the next big thing that they lose sight of the value of existing technologies with a proven record of helping people hear better.

Let me give you an example of what I mean. In the early 1990s, multichannel compression became a big deal, and justifiably so. Early multichannel products had low compression kneepoints, which allowed a wide range of speech inputs to be presented at an appropriate loudness level to the user, without the need for continual volume control adjustments. These products were labeled wide dynamic range compression, or simply WDRC. By the mid-1990s, multichannel WDRC products were available from all major manufacturers, and this technology had advanced to the point that it could give hearing aid wearers good audibility throughout the speech range.

How important was that? Well, as the renowned audiologist David Pascoe famously understated back in 1980, “Although it is true that mere detection of a sound does not ensure its recognition...it’s even more true that without detection, the probabilities of correct identification are greatly diminished.” In other words, you can’t understand speech that you can’t hear. So, giving patients access to the full range of speech sounds is a giant step toward providing speech understanding, generally the number one objective of a hearing aid fitting.

By now, the ability of multichannel compression to achieve this level of speech audibility is very old news, and newer hearing aid features are grabbing more attention. However, it’s doubtful that any of them has provided as much added benefit to patients as multichannel compression. The importance of this feature was no doubt a contributing factor in the recent research findings of Robyn Cox and colleagues (2014), revealing the similarities in both laboratory and real-world performance for entry-level products compared to premier instruments.

So, what is the parallel between multichannel compression and that restaurant that Yogi Berra said had become “too crowded”? Well, while the crowds may have led Yogi and his friends to look for a new hangout, Rigazzi's is now in its 60th year of satisfying its patrons with its traditional Italian cuisine. Maybe it’s not as hip as it was during the Berra years. But, just like good old multichannel WDRC hearing aids—and many other no longer glamorous strategies in hearing care (such as conscientious patient counseling and recommending assistive technology to enhance the value of a hearing aid fitting)—it’s still providing proven quality to people who appreciate that.

"Baseball is Ninety Percent Mental - the Other Half is Physical"

David Fabry: Earlier this month, I was listening to a story on NPR about how January 3rd is the busiest day of the year for signups to dating websites like Match.com, PlentyOfFish.com and the plethora of similar websites and apps out there. Apparently, as people spend more and more time with their phones, much of the dating world has moved there with them. The story continued with an interview with a brave young soul who decided to stop using apps for a month and date the old-fashioned way, by seeking out and making human connections without relying on a recipe of personality and value attributes driving the match. Listening to the story helped me to understand what Yogi was talking about with this aphorism.

Similar to the dating industry, the discipline of hearing aid selection, fitting, and follow-up has advanced greatly during the past thirty years. Modern prescriptive fitting approaches, including NAL-NL2 and DSLv5, ensure hearing aid gain and output levels provide audibility and comfortable loudness, on average, for listeners with a wide range of audiometric thresholds. These algorithms may be verified in-situ with real-ear measurements that use “live” or recorded speech mapping in a clinical environment. We also have reliable and easy-to-use speech-in-noise measurements, such as QuickSIN, HINT, or WIN. Some clinicians even have surround-sound systems capable of simulating “real-world” conditions. Sadly, with all of these evidence-based tools available to us for hearing aid fitting and selection, very few clinicians routinely incorporate them into their “best practice” protocol. Furthermore, many who do utilize them become more focused on “match” – as if we were fitting a pair of ears – rather than making a human connection with our patients to find out their hopes, fears, and expectations from hearing aids as they begin (or continue) their hearing journey. The parallels to the dating story became obvious – “The metrics say that we are supposed to be soul mates, but I really find that I can’t stand to be in the same room with you”! Fundamentally, we have to remember that properly-fit hearing aids do more than supply gain as a function of frequency; they have the power to change peoples’ lives.

Granted, I am a technophile and early-adopter, and have always tried to investigate new evidence-based tools that could provide patient benefits. But I must admit to also having fallen victim to getting lost in the data – the 90% “mental” part of the process, without focusing, as Yogi says, on the other “half”.

During the twenty years of my career that I spent in clinical practice, I learned first-hand that the “mental” aspects of real-ear measurements and speech recognition measures (in quiet and in background noise) were necessary – but not sufficient – to successful patient outcomes. If I didn’t engage the patient in the initial counseling and fitting process (the “physical” part), I found that I missed out on the opportunity to exceed patient expectations. Even worse, if I disregarded patient input and relied only on matching prescriptive target, speech recognition scores, and calculated audibility measures, the patient would often show up to the follow-up appointment with the tell-tale manufacturer bag, intending to return the devices for credit!

Ironically, once I learned to use my two ears and one mouth in direct proportion to their representation on my head, I became a more complete clinician and began to tap into the “other half” of the process mentioned by Yogi.

A specific example comes to mind from just a few years ago. I was scheduled to see a blind hard-of-hearing patient who had been labeled as “challenging” because of his reticence to consider new amplification. My immediate impression, based on his history, visual impairment, and degree of hearing loss, was that he was a “power junkie” who was used to using linear amplification. Furthermore, he was wearing five-year-old full shell devices, and I immediately began thinking about RICs or BTEs with directional microphones to improve his communication in background noise. Finally, I read the notes from the previous visits, which indicated that he had suffered full-blown panic attacks during the consultation, cementing my a priori opinion that he was resistant to change. Armed with my lab coat, a full patient load, and little time to spare, I stormed into the examination room, arrogantly thinking that, while others had failed, I could easily persuade him of the need to update to the latest technology. But he couldn’t see my lab coat or my credentials, and when I started to review details of his hearing health history, I couldn’t have been more wrong about the “90 percent” of the process. He was desperately concerned about the age of his hearing aids, and had resources available for their replacement. He had previously tried a new set of RICs and found that his spatial hearing was altered significantly in comparison the custom devices he was currently wearing (think about the importance of that to someone without vision). Most importantly, when we finally got to the source of his panic attacks, we were able to uncover that they were related to the fact that he became incredibly claustrophobic during the earmold impression process, because EVERY clinician he had seen made simultaneous binaural impressions, completely cutting him off from the outside world! The “easy” solution was to assign him as a “problem” case, when the problem was that we failed to focus on the “other” half of the equation: the “physical”, or practical, component that we had failed to uncover his concerns, fears, and expectations from the process. Only when I learned to use my “two ears and one mouth” in direct proportion to their existence on my head did I learn to uncover the secrets of Yogi’s wisdom.

In my family, we say it a little differently: when something really good happens, we say that “on a scale from zero to ten, that was an eleven”. I have found that in order to achieve amazing things, we have to apply what we know to what we do, sometimes in ways that don’t seem to add up. In turn, similar to Gestalt Psychology, the sum is greater than the whole of its parts – whether it is baseball or audiology.

"If the World Was Perfect, It Wouldn't Be"

Karl Strom: As already pointed out in this article, Yogi was something of an unintentional (quasi-Zen) philosopher in blue pinstripes. But what everyone loved about Yogi was his ability to extoll wisdom in a self-depreciating way that made people laugh, and nod their heads in agreement.

Baseball is a game that encourages the long view, along with the long ball. It is a marathon of 162 games in which even excellent teams rarely win more than 95 games (<60%). Since mediocre teams win 80-85 games, teams that do “the little things” are most likely to win those all-important 10 extra games. Here are a few things we might learn from Yogi.

Yogi wasn't perfect and he didn't pretend to be. Neither should you. Make sure your patients understand their hearing won’t be perfect after getting hearing aids, while informing them about the immense benefits of amplification. In particular, they should know about the limitations of hearing aid technology (e.g., hearing in noise and at a distance), and understand there are useful options like telecoils, assistive devices, and wireless accessories—and that you can help them with these either now or at a later date. These are the little things that can make a big difference.

Yogi was slow afoot, but he hustled, hit for power and average, played excellent defense, and was committed to winning. I’ve met and observed thousands of dispensing professionals. Although most would probably admit to having one or two professional weaknesses, the good ones have at least as many strong points—and they lead with it. Many are terrific at empathizing with and relating to patients, some are great clinicians and auditory-system sleuths, while others are artists at programming and fitting the hearing aid. But without exception, the great dispensing professionals hustle and have a deep commitment to patient care. They capitalize on and lead with their strengths, find ways to minimize their weaknesses (often with great staff), and flat-out hustle to create new advocates for their practice. If you build it—that is, a practice that continually hustles for successful outcomes—patients will come.

Yogi knew that trying to stretch a single into a double with two outs is usually a bad idea. This baseball axiom reminds us that there are times when the team needs to be smart and settle for what’s attainable right now; there are situations when you have to keep the game going in order to have any real chance of winning. MarkeTrak VIII (Kochkin, 2011) shows that, once a patient exceeds 3 office visits, the chances of him/her rating you and your services favorably plummet. Essentially, after 3 visits in a short period of time, you’re risking patient fatigue.

You’re also asking an awful lot of some patients. According to the US Census Bureau, 40% of people over age 65 have at least one disability, and two-thirds of these people have difficulty walking or climbing stairs and inclines. Visiting your office and their doctor’s office is a big challenge for them that can require elaborate arrangements. If you find this is the case for a patient, devise an efficient and effective strategy for maximizing every minute of their time with you and/or your staff.

None of the above is an endorsement for cutting corners or eschewing important steps in a best-practice protocol. It should also be acknowledged that some patients deeply appreciate and have no problem with 4+ visits. However, time and convenience is a big issue not just for some older patients but for some younger working adults too. We are entering an era where customizing services for the unique needs and lifestyles of patients will take on much greater significance (Taylor, 2015).

In a perfect world, hearing aids would completely “fix” the hearing problem, and time and convenience wouldn’t figure into the equation for patient satisfaction. But, as Yogi said, if the world was perfect, it wouldn’t be.

"If You See a Fork In The Road, Take It"

Carolyn Smaka: The other Yogi-isms have related to hearing aid selection, fitting, and post fitting counseling. I’m going to take a somewhat different approach, and discuss marketing. While success with our individual patients is paramount, our broader success as a profession is going to depend in part on our collective ability to keep our expertise and practices front and center in the public's mind when it comes to hearing care.

Consumer behavior is evolving, and we have seen a shift in how people discover, read and share information in the past ten years. What may have worked in the past in terms of marketing our practices may not yield the same results now. How do we market and advertise to engage today’s consumers in hearing care and hearing aids? By taking a fork in the road, as Yogi might advise.

Traditional v. Social Marketing. One fork in the road includes traditional marketing avenues such as yellow page ads, print ads in local newspapers, physician outreach and direct mail campaigns. The other fork includes online and social marketing, including a website, blog, social networking properties like Facebook, and email marketing. As compared to traditional marketing, social marketing has higher levels of consumer engagement and trust (O'Keefe, Pizzi, & Smaka, 2016). In a recent survey of audiology practice trends by the Academy of Doctors of Audiology, the primary marketing strategy utilized by the most successful practices was Web/social media (Amlani, 2015). This was followed by traditional newspaper advertising, and then direct mail. Strategies deemed as not helpful were television and radio advertising.

While many hearing care practices may be comfortable with traditional marketing, the social approach is new ground. “My patients are not online” may have been true a few years ago, but the data show that the majority of our patients – and those we are trying to reach with hearing solutions - are now online and using social media. According to the latest data from the Pew Research Center (2015a), 85% of adults use the Internet, and 65% of all adults use at least one social networking site. In addition, more than 60% of smartphone owners have used their device to look up health information in the past year (Pew Research Center, 2015b). Statistics from Google Analytics show the term “hearing aids” is searched about 74,000 times per month, and is second only to “tinnitus” (110,000 times per month) as the audiology-related term searched most often.

Search Engine Optimization (SEO). An important part of social marketing is search engine optimization (SEO), or improving a practice's ranking in search engines (O'Keefe, Pizzi, & Smaka, 2016). When a consumer is searching “hearing aids” online, a local audiology practice has the opportunity to appear in three places on the results page – in the paid listings (advertisements), in the local listings, and in the organic listings (non-paid search results).

Whether or not a practice should participate in the paid listings will depend on its overall marketing budget and strategy, and factors such as how much competition there is in the local market.

To be included in the local listings, a practice should claim the information for the business with the major search engines. This simply means submitting information about the business (business name, business address, etc.) using the online forms for the search engines - here are the links to complete local business information on Google, Yahoo and Bing.

For the organic listings, the ideal position is at or near the top of the first page, as numerous studies have shown that most people will not browse results thereafter (e.g., van Duersen & van Dijk, 2009). Online activities such as a current, mobile-friendly website with dynamic content such as videos, an active blog, and social networking properties (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Google+) will all positively impact a practice’s organic search ranking result. We refer to this as “online real estate”, and the more you own, the better you will rank.

A social marketing strategy will not only attract new customers, but also serve current customers. Current customers may browse their professional's website or Facebook page for directions, the telephone number, to look for parking information or walk-in hours, or to read more about new hearing technology promoted in an e-blast.

As the story goes, Yogi’s home in New Jersey could be reached by taking either of the two roads in a fork. In regard to marketing strategy for an audiology practice today, taking both roads in the fork is recommended. Developing a robust social marketing strategy does not mean abandoning traditional marketing. A cohesive blend of traditional and social marketing activities with consistent branding and messaging delivers the best results.

References

Amlani, A. (2015, November). The business case for disruptive innovations in audiology practice. Presentation at the Academy of Doctors of Audiology convention: Washington, D.C.

Bench, J., Kowal, A., & Bamford, J. (1979). The BKB (Bamford-Kowal-Bench) Sentence Lists for partially-hearing children. British Journal of Audiology,13,108-112.

Cox, R.M., Johnson, J.A., Alexander, G.C. (2012). Implications of high-frequency cochlear dead regions for fitting hearing aids to adults with mild to moderately severe hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 33(5), 573-87.

Cox, R.M., Johnson, J.A., & Xu, J. (2014) Impact of advanced hearing aid technology on speech understanding for older listeners with mild to moderate, adult-onset, sensorineural hearing loss. Gerontology, 60(6), 557-68.

Dillon, H., James, A. & Ginis, J. (1997). The Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 8, 27-43.

Gioia, C., Ben-Akiva, M., Kirkegaard, M., Jorgensen, O., Jensen, K., & Schum, D. (2015) Case factors affecting hearing aid recommendations by hearing care professionals. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 26(3), 229–246.

Killion, M. C., Niquette, P.A., Gudmundsen, G.I., Revit, L.J., & Banerjee, S. (2004). Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 116(4), 2395-2405.

Kochkin, S. (2011). MarkeTrak VIII: Reducing patient visits through verification and validation. Hearing Review, 18(6),10-12.

Lentz, W. (1972) Speech discrimination in the presence of background noise using a hearing aid with directionally sensitive microphone. Maico Audiological Series, 10 (9).

McShefferty, D., Whitmer, W., & Akeroyd, M. (2015, February). The just-noticeable difference in speech-to-noise ratio. Trends in Hearing. doi: 10.1177/2331216515572316.

Mueller, H.G. (1994) Update on programmable hearing aids (with an assist from Yogi Berra). Hearing Journal, 47(5),13-18.

O'Keefe, K., Pizzi, G., & Smaka, C. (2016, January). Demystifying social media: Beyond the buzz words. AudiologyOnline, Recorded Course 27161. Retrieved from: www.audiologyonline.com

Palmer, C., Bentler, R., & Mueller, H.G. (2006) Evaluation of a second-order directional microphone hearing aid: II. Self-report outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 17(3), 190-201.

Pascoe, D. (1980). Clinical implications of nonverbal methods of hearing aid selection and fitting. Seminars in Hearing, 1, 217-229.

Pew Research Center (2015a, October). Social networking usage: 2005-2015. Available at: https://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/2015/Social-Networking-Usage-2005-2015/

Pew Research Center (2015b, April). US smartphone use in 2015. Available at: https://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/03/PI_Smartphones_0401151.pdf

Ricketts, T.A., Hornsby, B.W.Y., & Johnson, E.E. (2005). Adaptive directional benefit in the near field: Competing sound angle and level effects. Seminars in Hearing, 26(2), 59-69.

Sarampalis, A., Kalluri, S., Edwards, B., & Hafter, E. (2009) Objective measures of listening effort: effects of background noise and noise reduction. Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research, 52(5),1230-40.

Taylor, B. (2015). The “Good Enough” era and hearing healthcare. Hearing Review, 22(5),10.

Thibodeau, L. (2014). Comparison of speech recognition with adaptive digital and FM remote microphone hearing assistance technology by listeners who use hearing aids. American Journal of Audiology, 23(2), 201-210.

US Census Bureau. (2014, December). Older Americans with a disability, 2008-2012. American Community Survey Reports (ACS-29). Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/acs/acs-29.pdf

Van Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2009). Using the Internet: Skill-related problems in users’ online behavior. Interacting with Computers, 21, 393-402.

Wilson, R.H. (2003). Development of a speech in multitalker babble paradigm to assess word-recognition performance. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 14, 453-470.

Wu, Y. (2010) Effect of age on directional microphone hearing aid benefit and preference. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21, 78–89.

Extra Innings

Gus Mueller: I've always been a serious baseball fan, and played a lot of baseball, so I have many stories to tell, but one that stands out happened in 1993. I moved to Colorado in 1991, and immediately started following the Colorado Rockies, a team that only existed on paper at the time—a new expansion team for the National League. They played their first-ever home game on a gorgeous Colorado afternoon, April 9th of 1993. I was part of the opening day major league record-setting crowd, a record which still stands, of 80,227 (Section 525, Row 5). Sitting next to me were fellow audiologists Jerry Northern, Bob Traynor and Steve Ackley. Our first batter, Eric Young, on a 3-2 count, hit a home run. I have never before or after been part of such an enormous cheer at a sporting event.

Brian Taylor: It was the spring of 1982, my freshman year of high school and the peak of Fernandomania. Somehow I managed to make the varsity baseball team. For the first half of the year I was either on the bench or stuck in right field - the Siberia of America’s pastime. Having played Little League baseball for several years, I had developed a decent curveball. Like good judgement and unblemished skin, a curveball, thrown for strikes, is a rare commodity among teenage boys. So, it was in a fit of apparent desperation that the coach inserted me into a crucial late game situation. I managed to save the game with a couple of strikeouts. Thereafter, for three glorious weeks that May, as my favorite team the Milwaukee Brewers established their dominance on a run to their first and only World Series, I was able to close games with an indelibly slow curve. For the next three years of high school I never regained the magic of the slow curve I threw in the spring of 1982. Now it’s 2016, the Brewers have yet to reach another World Series, Fernando Valenzuela is retired in Mexico and I’m throwing metaphorical curveballs for the Hearing News at Hearing Health & Technology Matters.

David Kirkwood: Yogi Berra starred in the highlight reels of my 60-plus years of rooting for the Yankees. Although the Yanks reached the World Series nearly every year of my childhood, at age 12--for various reasons--I had never seen them win one. Late in game seven of the 1958 World Series, I felt doomed to disappointment. The situation was bleak. The Milwaukee Braves had just tied the game 2-2, scoring off New York’s Bob Turley, who was weary after pitching 14 innings in the past 3 games. The Braves’ hurler was Lew Burdette, who had practically single-handedly beaten the Yanks the year before. In the top of the eighth, he had just fanned Yankee superstar Mickey Mantle, leaving two outs and the bases empty when Berra came to bat. Yogi was mired in a slump, batting under .200 in the Series. But, true to his reputation as a great clutch hitter, he lined a double off the right-field wall. That lit the spark that led to a 4-run rally and gave me my ultimate joy as a Yankee fan.

Dave Fabry: Growing up in Green Bay, Wisconsin, in the 1960s meant that it was pretty much football 24/7/365. To make matters worse, Hank Aaron and the Milwaukee Braves left the state for Atlanta after the 1964 season, and the Brewers didn’t arrive on the scene until 1970, meaning that I was a baseball “orphan” during my formative years from age 5-11. When I moved to Minnesota to start college in 1977, I became a Twins fan, and remain one to this day (despite the fact that my two favorite football teams are the Packers and whomever plays the Vikings). Among my favorite memories was waiting in line overnight, outside Rosedale Mall, to purchase tickets for the 1987 World Series against St. Louis. I attended all four games in one of the worst ballparks to grace the major leagues (The Humphrey Dome), but the Twins won all of their home games to clinch the first major sports championship in decades for the Twin Cities. I also attended game seven of the 1991 Series against Atlanta, when Jack Morris pitched a 10-inning shutout to win the series. There is nothing like the feeling of watching your team win it all, and the Twins have brought me considerable joy. They now play their games in one of the most beautiful parks in the league (Target Field), and I would love to host you for a game if you visit Minnesota in the summertime.

Karl Strom: I grew up in rural northern Minnesota where hockey is a religion and baseball is something you play after the lakes and rivers melt—in July. Nevertheless, baseball was always my sport, and I wasn’t too bad at it. Today, after thousands of repetitions, my children can recite virtually all of my career highlights from sandlot and high school ball, including riveting tales of a triple play and my invention of a rather spastic hybrid Joe Morgan/Rod Carew batting stance. But nothing sends them rolling their eyes and fleeing for their rooms like the recounting of my one-hitter in the tiny town of Chisago Lakes, Minn. Wait! Stay right there. Don’t move. “It was a cold gray day when the lanky right hander took the mound for the Two Harbors nine…”

Carolyn Smaka: I come from a long line of Yankees’ fans. I grew up in upstate New York near the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. This is my favorite Yogi story, from my dad. "A few years ago, your mother and I decided to take a drive to Cooperstown for the day. When we arrived, the streets were crowded, and we knew there must be a special event going on. Then we saw that there were famous players seated at tables all along Main Street, signing autographs and selling memorabilia. Many of the tables required an expensive purchase or fee for an autograph or photo from the player. As we walked along, we came upon a table where seated were none other than Yogi Berra and Ron Guidry! They were taking good-natured jabs at one another, laughing, and horsing around. They were calling out to kids in the street to come over and take a photo with them, no fee required. Here was one of the greatest baseball Hall of Famers – a legend – making himself approachable to fans of all ages. What we thought would be an ordinary Sunday drive turned out to be a day I'll never forget."

Cite this Content as:

Mueller, H.G., Fabry, D., Kirkwood, D., Smaka, C., Strom, K., & Taylor, B. (2016, January). 20Q: Hearing aids - the future ain't what is used to be! AudiologyOnline, Article 16150. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.