From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

Welcome to 2025. Here at AudiologyOnline we’re celebrating the 15th year of the 20Q column. Some of you regular readers might recall that it actually originated back in 1994 over at The Hearing Journal, when the column was titled Page Ten. So, if my math is correct, that’s a total of 372 columns, over 7,000 questions...but who’s counting?

I have to say, my all-time favorite was the one written by The KEMAR back in 2006.

Among many other things, he/she (depending on the number of neck rings) explains how he/she got the first name of “The,” and how it only marginally relates to the middle name of Smokey The Bear. But I digress.

As you’ve maybe noticed, we always try to have a few articles each year at 20Q that relate to current audiology innovations and issues. This past year, for example, we devoted two different columns to AI in audiology, one mostly addressing hearing aids and hearing aid fitting by Josh Alexander, and another focused more on the big picture of how AI and the audiology profession interact, written by Don Nielsen. We also had Andy Bellavia give us an interesting overview of Auracast; where we are, and where we are going. And, on a topic that sometimes can be controversial—the impact of hearing aid use on cognitive decline—Kevin Munro and Piers Dawes did a nice job of discussing what the science tells us.

There are other times at 20Q, however, when the topic isn’t about anything new at all. Last October, for example, we enjoyed Chris Spankovich’s review of what is normal hearing. Similarly, a few years back, I recruited Ben Hornsby to help me write an article on monosyllabic word recognition testing. Ben’s immediate (very reasonable) question was: “What the heck could we say about that topic that everyone doesn’t already know?” Despite the fact that all the references were over ten years old, some from 30 or more years ago, it has become the most read article at AudiologyOnline.

So keeping that recipe in mind, this month I’m going to write about self-assessment inventories—the ones used with hearing aid selection and fitting. You’re right, not late-breaking news; something that you all are familiar with. My observation, however, is that for no really good reason, these self-reports are not readily embraced by most audiologists today. The Mystery Question Woman for this month’s 20Q might be similar to some of you. She knows about these inventories, has dabbled with them, but doesn’t really see them as part of her daily routine. We’ll see if I can move her a little toward my way of thinking.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Hearing Aid Selection and Fitting - The Role of Self-Report Inventories

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Describe the basis for using self-assessment inventories in the fitting of hearing aids.

- Describe what inventories can be given before the hearing aid fitting

- Describe inventories that can be used as outcome measures.

1. I haven’t really thought much about these inventories for quite a while. Are you here to tell me about some new ones that are available?

There are a few relatively new ones, some of which focus on hearing-aid related domains that we haven’t thought much about in the past. We certainly can talk about them. We can’t forget, however, that there also are some excellent validated scales that have been around for more than 20 years, which don’t receive the attention that they should.

2. You use the term “self-assessment,” but I also see them called “outcome measures.” Same thing?

Sometimes, “yes,” but other times “no.” As the name suggests, a self-assessment inventory is completed by the patient, and reflects his or her individual thoughts and beliefs regarding the given topic. Let’s take the popular International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA; Cox & Alexander, 2002). The scale is indeed self-report, and is geared to assess seven core outcomes related to hearing aid use. So yes, it’s both self-assessment and an outcome measure.

Another popular scale is the Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory (RHHI; Cassarly et al., 2020)—a scale that is the merging of the HHIE and HHIA. This is an inventory that measures the psychosocial handicap that might be caused by a hearing loss. Commonly, this is administered at the patient’s first clinic visit, to assist in counseling, and help determine amplification needs. So, when used for this purpose, it certainly is self-assessment, but not an outcome measure. The RHHI, however, also can be used as an outcome measure—given again to the patient after several weeks of hearing aid use, to determine if the use of hearing aids has had a positive psychosocial impact (e.g., aided scores better than unaided).

We need to also consider, that there are many other clinical outcome measures related to the fitting of hearing aids that are not self-assessment. Probe-mic measures to assess appropriate audibility. The aided QuickSIN to determine if the desired improvement in speech-in-noise understanding was achieved. Aided LDLs, to ensure that the MPO was programmed correctly.

3. Got it. In a previous work setting, we sometimes conducted self-assessment scales, but I’ve sort of drifted away in recent years. Are these actually considered to be part of best practice?

Most certainly. The 1998 Academy of Audiology guidelines, for example, sum up their recommendations with the following:

- Each patient should receive formal self-assessment instrument(s) and/or inventory(s) prior to fitting to establish communication needs, function, and goals.

- Goals should be patient specific and composed of both cognitive and affective characteristics.

- Post-fitting administration of these instrument(s) is necessary to validate benefits/satisfaction from amplification.

Here are a couple of examples from the most recent (2021) hearing aid fitting standard from the Audiology Practice Standard Organization (APSO; see Mueller et al., 2021, for review):

Item #3. A needs assessment is conducted in determining candidacy and in making individualized amplification recommendations. A needs assessment includes audiologic, physical, communication, listening, self-assessment, and other pertinent factors affecting patient outcomes.

Item #14. Hearing aid outcome measures are conducted. These may include validated self-assessment or communication inventories and aided speech recognition assessment.

4. Can I assume that most of these self-assessment inventories are valid and reliable?

Good question—if you’re not collecting information in the proper way, it might not be worth very much. There are many factors to look at when designing a self-assessment scale. Not surprisingly, the person who explained all this in the most organized way was Robyn Cox (Cox, 2005). The following is adapted from her article, as well as some minor additions from Ricketts et al. (2019). Cox (2005) suggested that there are four practical elements the audiologist should consider:

- Clinician burden: This relates to the effort required for the audiologist in learning how to administer, score and interpret the test. Does learning about the test require a 1-day instructional course, or a 5-minute YouTube tutorial?

- Patient burden: This refers to the difficulty encountered by the patient in reading, understanding, and completing the items of the questionnaire. The reading level and cognitive level of both the items and the instructions should be considered.

- Scoring: Busy clinical audiologists are looking for a questionnaire that is convenient, quick, objective, and easy to score. Automated scoring is usually preferred but not always available. Some inventories have their own scoring software, and three scales are included in the Noah 4 Questionnaire Module.

- Utility: This relates to the extent to which the data from the scale can be readily applied for treatment, planning or counseling—an immediate use of the findings usually is desired.

In her article, Cox (2005) also identifies four technical elements that we should consider when evaluating different self-assessment inventories:

- Norms: The availability of published normative data is very helpful to the audiologist for patient counseling. Patients typically are very interested to hear how they are performing compared to others with similar hearing loss, people their age with normal hearing, or even young normal-hearing listeners.

- Reliability: This relates to the consistency of responses for a given inventory across different tests and different testers. Critical differences have been calculated for several inventories—that is, when are two different scores truly different, or when is a given score significantly different from the norms.

- Validity: We would consider an outcome measure valid if it truthfully measures what it purports to measure. Benefit? Satisfaction? Quality of Life? In this regard, it should produce scores that have a predictable relationship with other validated outcome measures that purport to measure the same domain.

- Sensitivity: Will a questionnaire detect performance or changes in performance that are of interest to the audiologist? It’s very possible that a scale may effectively differentiate aided versus unaided, but will not be very good at pulling out more subtle amplification differences. Some scales might have several questions focused only on benefit, where another scale might only have one, or none at all.

When an inventory has been extensively researched and the findings published in peer-reviewed journals, you can assume that the last four technical considerations have been addressed. You will mostly want to think about the first four I mentioned.

5. Well, that's good, as these are the things I think about. Regarding “utility,” I guess the notion is that these scales will give me insights that will be useful in the overall treatment plan.

Correct. One way to think of the usefulness of these scales relating to hearing aid fitting outcomes is evaluating “treatment efficacy,” something reviewed nicely by Barbara Weinstein years ago (Weinstein, 1997). Treatment efficacy is tied to three different aspects of the selection and fitting process: effectiveness, efficiency, and effects:

- Treatment effectiveness: Do hearing aids provide appropriate audibility, improve speech intelligibility in quiet and for listening in background noise, and restore normal loudness perceptions?

- Treatment efficiency: Are certain brands of hearing aids, or specific hearing aid settings/adjustments better than others for improving speech understanding? For patient overall satisfaction?

- Treatment effects: Does the use of hearing aids improve the patient’s social and emotional well-being, and the patient’s overall quality of life?

All three of these points must be considered when treatment efficacy is evaluated. A slightly different way to look at this process, reviewed by Larry Humes in one of our 20Q articles (2022), is to consider the comprehensive model of healthy function developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), commonly referred to as the WHO-ICF (WHO, 2001). This model has three primary components: healthy bodily functions or no body impairments, no activity limitations, and no restrictions on participation in society. The audiogram provides a pretty good measure of impaired function, but validated self-assessment measures are very useful to determine if activity limitations and participation restrictions are present.

It’s unlikely that a single outcome measure will address all the components of efficacy, or, the three components of the WHO classification, and therefore, different assessment scales usually will be necessary. The main purpose of these measures is to use this information for clinical decisions regarding patient care. There also might be administrative reasons for collecting and maintaining this information.

6. Administrative reasons?

Sure, here are a few that come to mind, some of which are adapted from previous publications (Bentler et al., 2016; Ricketts et al., 2019):

- Comparison of different fitting procedures across groups of patients: You always fit your hearing aids to the NAL-NL2 targets with careful verification and adjustment using probe-mic measures. Your colleague, however, defers to the manufacturer’s first-fit proprietary setting. Will both groups of patients have the same benefit and satisfaction with hearing aids in the real world? Should one of you be changing your philosophy?

- Comparison of circuitry across groups of patients: A major hearing aid company just introduced a new product with AI-driven processing and deep neural networks. You’re pretty happy with the product from a different manufacturer that you’ve been dispensing. It’s important to know in your own setting if “new means better,” especially when the newer circuitry adds several hundred dollars to the cost of the hearing aids. If your patients were fitted with the new product, would they observe/report improved benefit and satisfaction? If yes, you might consider switching to that product.

- Counseling effectiveness across groups of patients: Does extra counseling effort result in improved real-world satisfaction and benefit with hearing aids? That is, if you have changed counseling techniques, maybe added time to the hearing aid fitting appointment, do the outcomes change for your patients? What if you added a week-end rehabilitative course for your patients? Improved satisfaction?

- Comparison of different dispensing sites or personnel: If you are the manager of a clinic that has several audiologists, and/or different offices, you might want to compare the patient-reported outcomes as a form of quality control. Does satisfaction with hearing aids differ significantly among audiologists or offices?

- Documentation of service effectiveness: You know you do a good job, but do you have data to prove it? Are your patients more satisfied than the average person fitted with hearing aids? For example, how often does their IOI-HA score exceed national norms? How often is satisfaction better than MarkeTrak data? How often do you meet your patients’ expectations related to their established fitting goals? Assuming your findings are all good, this is great information to pass along to curious shoppers and new candidates.

7. Let’s say that I might like to get back to doing some self-assessment inventories again. Where do I start?

A reasonable starting place, on the day of the initial patient visit, would be to collect information that will supplement the audiogram—determining if there is an impairment? We know that there are some people with “normal” hearing thresholds, who will report considerable hearing problems—in the language of the WHO-ICF, activity limitations and/or participation restrictions. A useful scale to administer at the initial patient visit, one that certainly is time-tested, is the RHHI (Cassarly et al., 2020). Recall earlier, I mentioned that this is the revised version of the HHIE/HHIA, scales that have been in common use for decades (see Mueller et al, 2013, for review). For clinical purposes, the screening 10-item version (RHHI-S; See Appendix) is all you need, as this has been shown to have good reliability. I might add, that research has shown that the RHHI-S will give you results very similar to the HHIE-S, which tend to be very similar the HHIA-S (Cassarly et al., 2020), so if you don’t have the RHHI-S handy, using one of the other two is still much better than none at all.

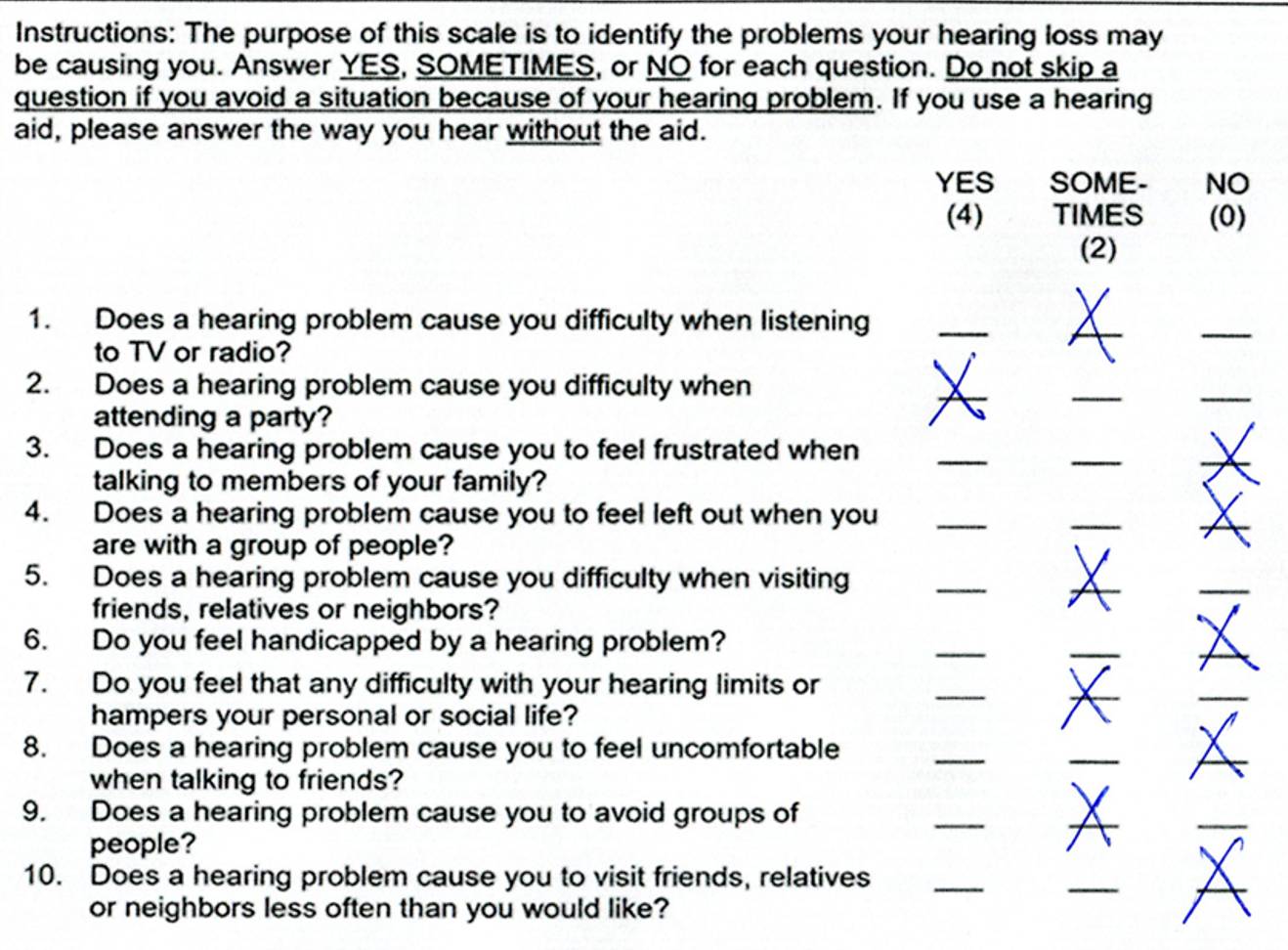

Shown in Figure 1 are RHHI-S findings from a 76-year-old male, who has essentially normal hearing through 1000 Hz bilaterally, sloping down to 50 dB at 3000-6000 Hz, with right and left earphone QuickSIN scores of 2-3 dB SNR Loss. His RHHI score of 12 is maybe a little worse than you might expect, placing him in the mild category. Will this influence your thinking regarding the fitting of hearing aids? Maybe. If you do fit him with hearing aids, it certainly gives you five areas to focus on when you use this same scale as an outcome measure.

Figure 1. Unaided RHHI findings for patient with mild-moderate bilateral downward-sloping hearing loss. Click here for a larger image.

8. I see that there might be value, but this is just one more thing that eats up precious appointment time.

Not really. This is a very easy questionnaire to complete, and it could simply be handled by your front desk people when the patient checks in. By the time you see it, it’s completed and scored. Patients today are used to filling in questionnaires prior to their appointments (which is why you have them arrive 15 minutes early).

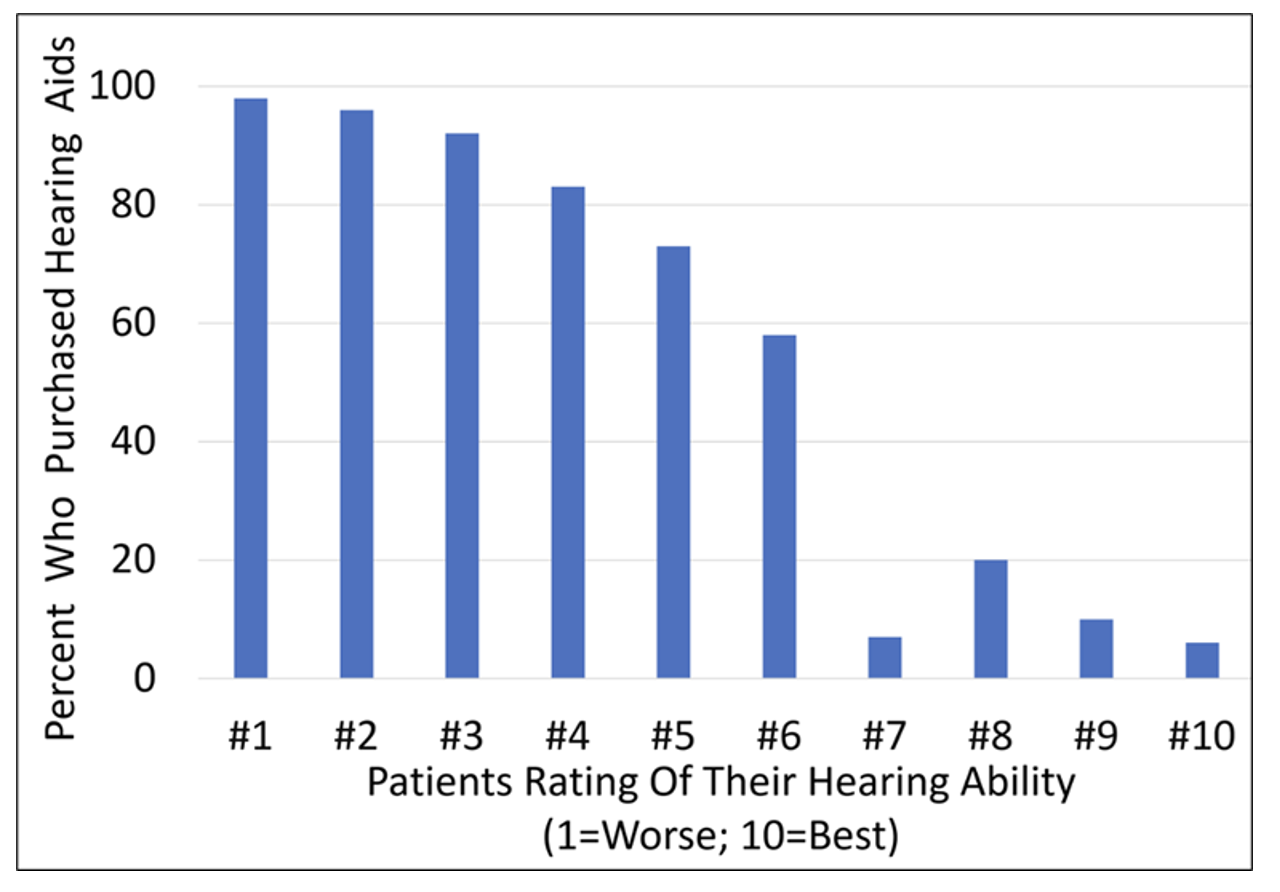

Since you bring up the time investment involved in doing these measures, here is a study that I’m sure you will like. Catherine Palmer and colleagues reported on using a “one-question” inventory! In a retrospective study of over 800 adults, aged 18-95 years, Palmer et al. (2009) examined the relationship between the patient’s rating of his or her hearing ability and their subsequent decision to purchase hearing aids. The patients were asked the following question: “On a scale from 1-10, 1 being the worst and 10 being the best, how would you rate your overall hearing ability?”

The answer to the above question was then compared with whether the patient purchased hearing aids. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Hearing aid purchase compared to rating of pre-fitting unaided hearing ability. (Adapted from Palmer et al., 2009).

As we would predict, those that rated their hearing very poorly (e.g., #1, #2 or #3), were very likely to obtain hearing aids—92% or greater. And, only a small percent of those who stated that had relatively good hearing (ratings of #7 to #10) purchased hearing aids (20% or less). What perhaps is most interesting in the findings, is the large difference between the #7 rating (7%), and the #6 rating (58%). While only 1 increment apart, the purchase rate increases by 51%! Obviously, there is something about that rating level. If we look at the transtheoretical stages of change model, we might guess that this relates to the patient going from contemplation and planning to “action” (Mueller and Taylor, 2024).

9. Interesting, something I could easily add. Getting back to the RHHI-S, are you thinking that this would be the only structured scale that I would need to complete at the first appointment?

Probably not. As you noticed, the RHHI-S focus is on the psychosocial aspects of having a hearing loss. I’d like to know a little more about the disability (activity limitations)—speech understanding in quiet and in noise for example. A good scale for obtaining that information is the Abbreviated Profile for Hearing Aid Benefit (See Appendix), known as the APHAB (pronounced "aye-fab").

10. I’ve certainly heard of the APHAB—that’s been around for quite a while, right?

Yes, it goes back about 30 years (Cox & Alexander, 1995). The APHAB is a shortened version of the original PHAB, two of the many excellent self-assessment scales developed by Robyn Cox and her colleagues. You can view it in the Appendix and download it directly from the University of Memphis Hearing Aid Research Lab.

It’s 24 questions divided into four categories of 6 questions each: listening in quiet, in background noise, in reverberation and aversiveness to loud sounds. Each statement is rated on a 7-point scale going from A=Always (99%) to G=Never (1%). The statements are carefully designed so that if the patient has a fairly severe hearing loss, “A or B” might be the correct response for some statements, but “F” or “G” might be the appropriate response for others—this helps identify the patients who are not carefully reading the statements or may not have the cognitive skill to provide reliable results. The APHAB is probably the most used self-assessment scale worldwide, and has been translated into over 20 different languages. The test can be administered via paper/pencil or from a laptop. The scoring does get a little tricky, but there is handy software available from the HARL. The APHAB software also is included in the HIMSA Noah 4 Questionnaire Module. The software will not only score the APHAB but will plot out the findings to assist in interpretation.

11. So, what exactly are these APHAB results going to tell me?

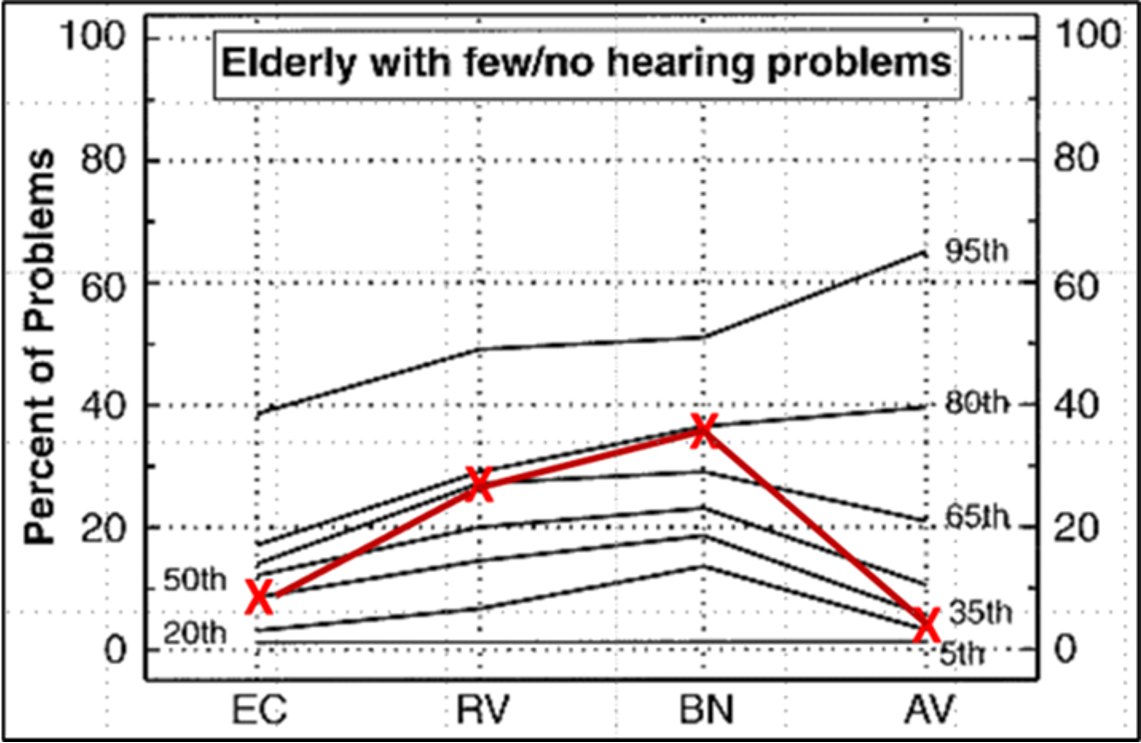

It would take a while to go through everything, but here are a few examples—we’ll just talk about two of the four scales, which is what we usually focus on for the unaided results: Scale EC: ease of communication (i.e., listening in quiet), and Scale BN: listening in background noise. Once I see these scores (percent of problems), I would first do a quick check to see if the percent of problems for the EC were in general agreement with the audiogram thresholds and unaided SII (if available), and if the percent of problems for the BN were consistent with my QuickSIN findings. Then also consider if the relationship between these APHAB measures, the RHHI findings, and my case history, all makes sense.

Following that initial quick review, I’ll take a look at couple of plots. For our example, I’m using the APHAB findings for the patient I mentioned earlier with the mild bilateral high frequency loss. In Figure 3, you see his scores for the four different APHAB subscales. This is “percent of problems” so low scores are good. Cox and colleagues (e.g., Cox, 1997) have provided us with several charts like this, showing percentiles for different areas of interest (normal hearing, hearing loss, unaided, aided, etc). What we are looking at in Figure 3 is his unaided APHAB compared to the norms for “elderly with few/no problems” (there is a similar chart for young normal hearing). The speech-in-quiet scores are quite good (EC Scale), only 10% problems (35th percentile). The speech in background noise (BN Scale) is at the 80th percentile (elderly individuals with normal hearing), so actually pretty good, and about what I might expect given his QuickSIN performance. In case you’re curious, his BN Scale score would be around the 5th percentile when referenced to the APHAB unaided norms for those who have hearing loss.

I think you can see how these findings might help you in your treatment plan, and your pre-fitting counseling. Moreover, you now have a baseline that you can use to measure benefit, if indeed this patient is fitted with hearing aids, something that hopefully we can talk about later.

Figure 3. Unaided APHAB scores for our 20Q Sample Patient. EC: ease of communication (listening in quiet), RV: listening in reverberation, BN: listening in background noise, and AV: aversiveness (annoyance of loud sounds).

12. I’m not totally sure I want to do all this, but you make good points. What’s next?

Let’s assume our patient decides to purchase hearing aids, and is now back for the fitting. At this point, we’re going to introduce what is perhaps the most useful, and popular self-assessment scale—the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (Dillon et al., 1997), fondly called the COSI (as in “cozy”). Until you and the patient go to work, the COSI is a blank sheet - you can view it in the Appendix or download it directly from www.nal.gov.au. The process begins by having the patient identify up to five specific listening situations in which he or she would like to hear better. Some patients will happily list even more; other patients struggle to come up with two or three. Try to have at least three. It is important to make each item as specific as possible. “Hearing in background noise” is not specific enough. After some questioning, this item might be narrowed to “Hearing my friends while playing in the pool league in the Ryder bar.” Once one situation is identified, you then move on and establish other situations. Some patients will try to list the five most difficult listening situations that they can remember. They often need to be coaxed to list more common listening situations, which in actuality, might be more important, simply because they happen every day.

After all situations are identified, it is then helpful to go back and review and rank all situations. Simply place a “1” for most important, “2” for second most important, and so on in the box to the left of the item. Often, the item that the patient mentions first is something that just happened recently but is not the most important.

13. I get it. The patients more or less design their own scale, which I can then use later to assess benefit, right?

Right you are. And you see why the COSI is popular: low clinician burden, low patient burden, easy to score, and it most certainly has high utility, as you have very personalized identification of the major communication problems.

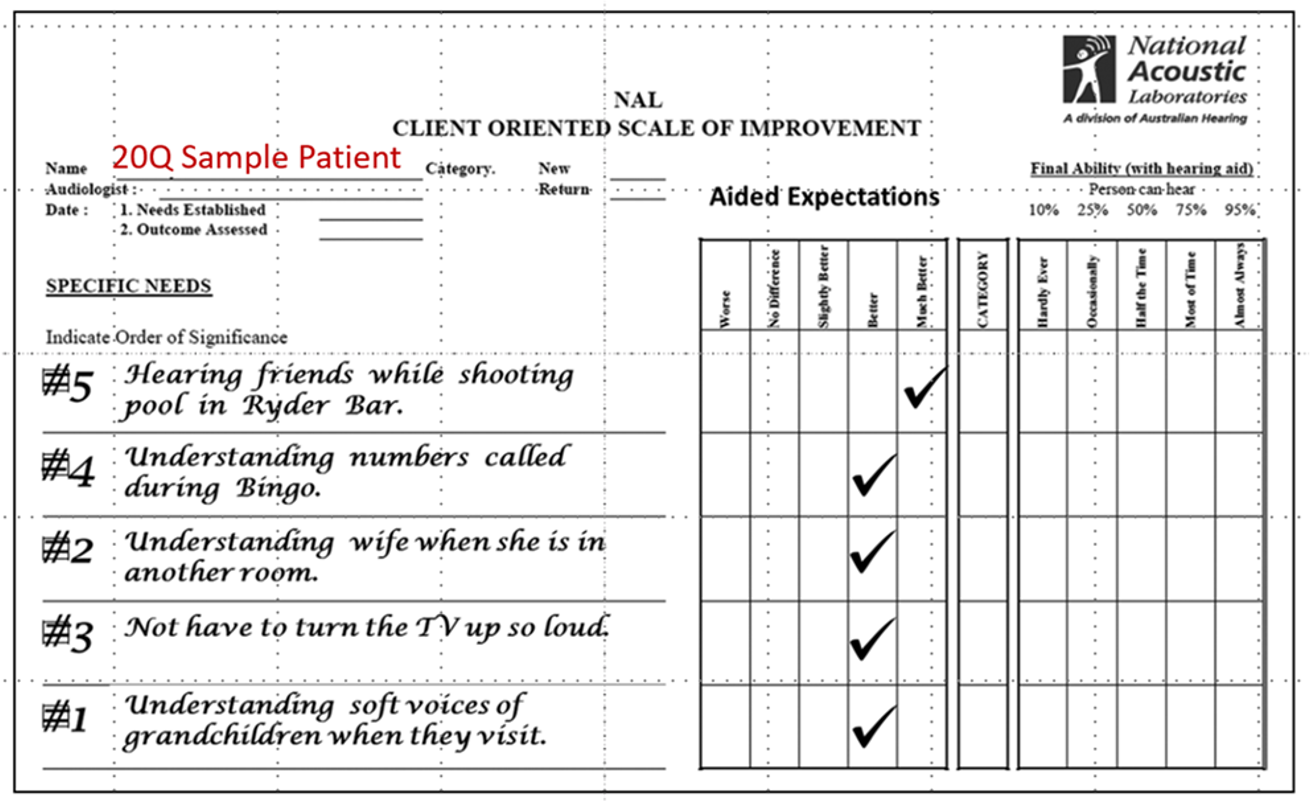

Before we get to the post-fitting ratings, however, I’d like to toss out the idea that on the day of the fitting, you also measure the patient’s expectations for these nominated items. Here is an example (Mueller et al., 2017). In Figure 4, we have the five items that were selected by our 20Q patient, and to the left of each item is the importance rating given to that item. I have slightly modified the labeling of the original COSI form, so now the ratings that you see to the right of each item are the patient’s expected outcomes, rather than actual degree of change. This form was completed on the day of the fitting.

First, notice that understanding grandchildren, was the last item this patient thought of, yet after some thought and discussion with his wife, it was given #1 priority. Conversely, the first thing he mentioned was understanding at his favorite watering hole (an event that had just happened the night before), yet this ultimately was given #5 priority, as upon reflection, he realized he only visits the Ryder bar a couple times a month—a very small percentage of his total communication needs (playing Bingo, however, is every Friday night in the school gym!). Note that overall, his expectations are fairly high, maybe a little unrealistic. We tell him this, but assure him we will give it our best shot.

Figure 4. Expectation ratings for our 20Q Sample Patient for the five listening needs that he selected. Click here for an enlarged image.

14. If I’m following you, our next step with this patient is to actually assess aided benefit?

Right, when you do that, however, varies somewhat from clinic-to-clinic. If you’re concerned about the 30-day return policy, and making sure you identify any potential problem prior to this, then I’d say around the 3-week post-fitting time frame. For some, maybe most patients, their benefit will continue to increase after the three-week time-fame, as they continue to adapt to using their hearing aids—6-8 weeks might be a better sampling point.

I know we just finished talking about the COSI, but recall that you also have unaided RHHI and APHAB results, so a good starting point at the post-fitting visit would be to obtain aided results for these two scales. There is considerable data showing the degree of aided benefit that can be expected, especially for the APHAB (e.g., see Cox 1997, or HARL web site).

Regarding the COSI, when the patient returns for his or her post-fitting visit, the previously completed form is then brought out for the patient’s ratings. It is common that the patient doesn’t remember all of the exact items he or she selected (and may have new items based on recent listening experiences). For example, Mormer and Palmer (2001) report that after three weeks of hearing aid use, 96% of the patients nominated two items the same, but no patient who originally nominated four items, nominated the same four items on the return visit. Although this lack of consistency can slow down the process a little, because the COSI is such a flexible instrument, item selection can be dealt with quite easily. It is easy to cross out listening tasks that are no longer meaningful, add new ones, or simply have the patient rate only the situations that are consistently on the list (Mueller et al., 2017).

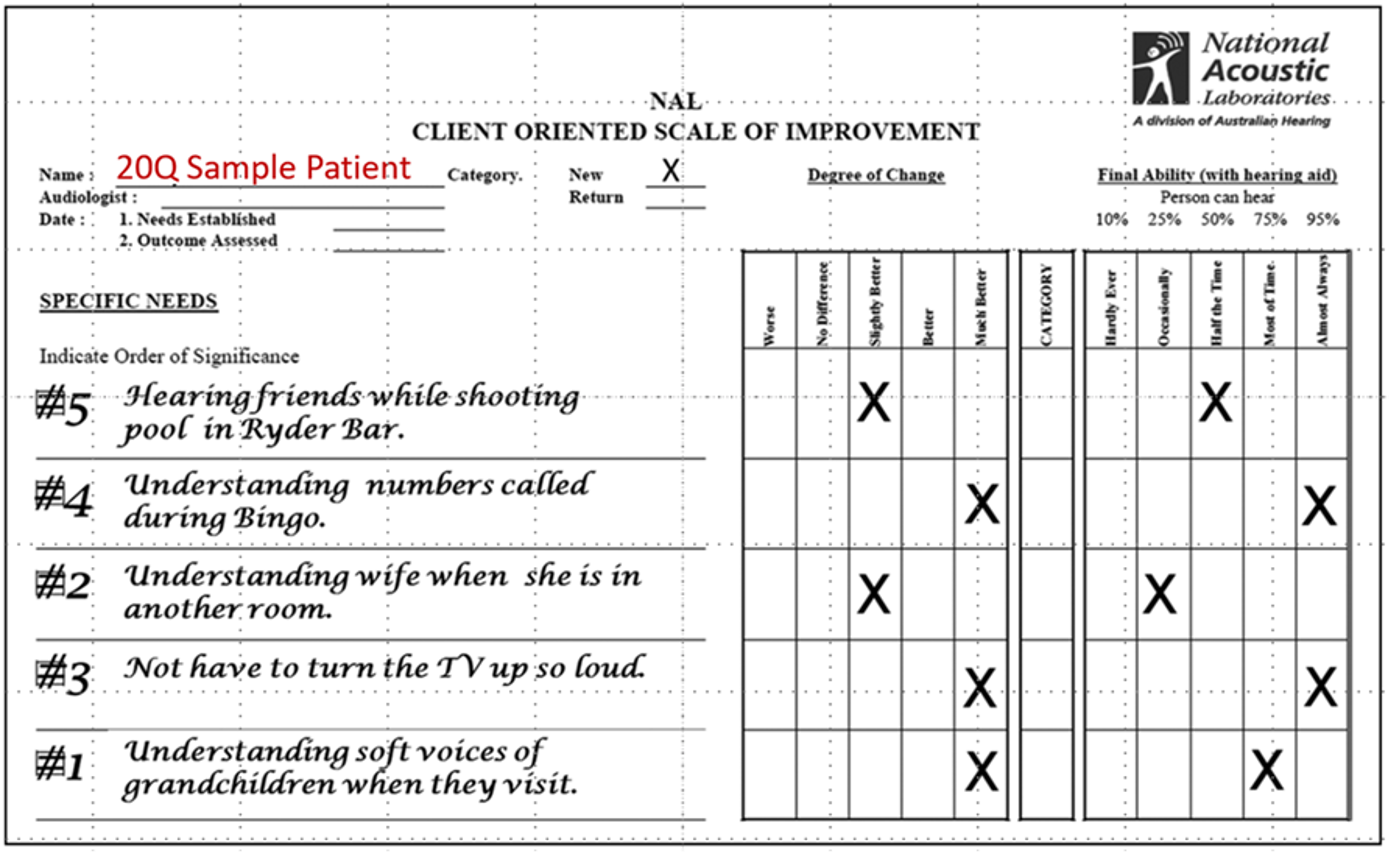

As you can see on the form (Appendix), benefit on the COSI can be assessed in two different ways: Degree of Change (improvement provided by the hearing aids) and Final Hearing Ability with Hearing Aids (an absolute measure of communication ability). It is typical to see a similar pattern for these two different ratings, but sometimes a difference is noted. For example, a patient with a fairly severe hearing loss who works in a demanding listening situation might rate his Degree of Change as “Much Better,” but have only a Final Hearing Ability of 50%. I’d suggest having the patient rate both categories because doing so may bring up key issues that need to be addressed.

15. Do we have the results for our special “20Q Patient?”

We do. The COSI results for our pool-playing grandfather are in Figure 5. We don’t initially show him the sheet he completed earlier regarding his expectations—we’ll bring that out later. The good news—he reports doing “much better” in 3 of the 5 categories. He notes some improvement with hearing his wife from a different room, but we are falling below his expectations for this category (see Figure 4). It may be that given the difficulty of this listening situation, this might be as good as it gets, but something we want to talk about. Overall, I’d be pretty happy with these results. It’s easy to see how the use of the COSI in this manner facilitates post-fitting counseling.

Figure 5. Completed COSI for our 20Q Sample Patient following several weeks of hearing aid use. Click here for an enlarged image.

16. Can we assume that when the patient is reporting good benefit that they also are satisfied?

There usually is a fairly strong correlation between benefit and satisfaction, but they really are two different domains. So, you guessed it . . . yes, I’m going to suggest you also conduct a self-assessment for satisfaction. One that has been carefully researched is the Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life, known as the SADL, as in “Saddle.” Yet another scale developed by Robin Cox and colleagues (Cox & Alexander, 1999; See Appendix).

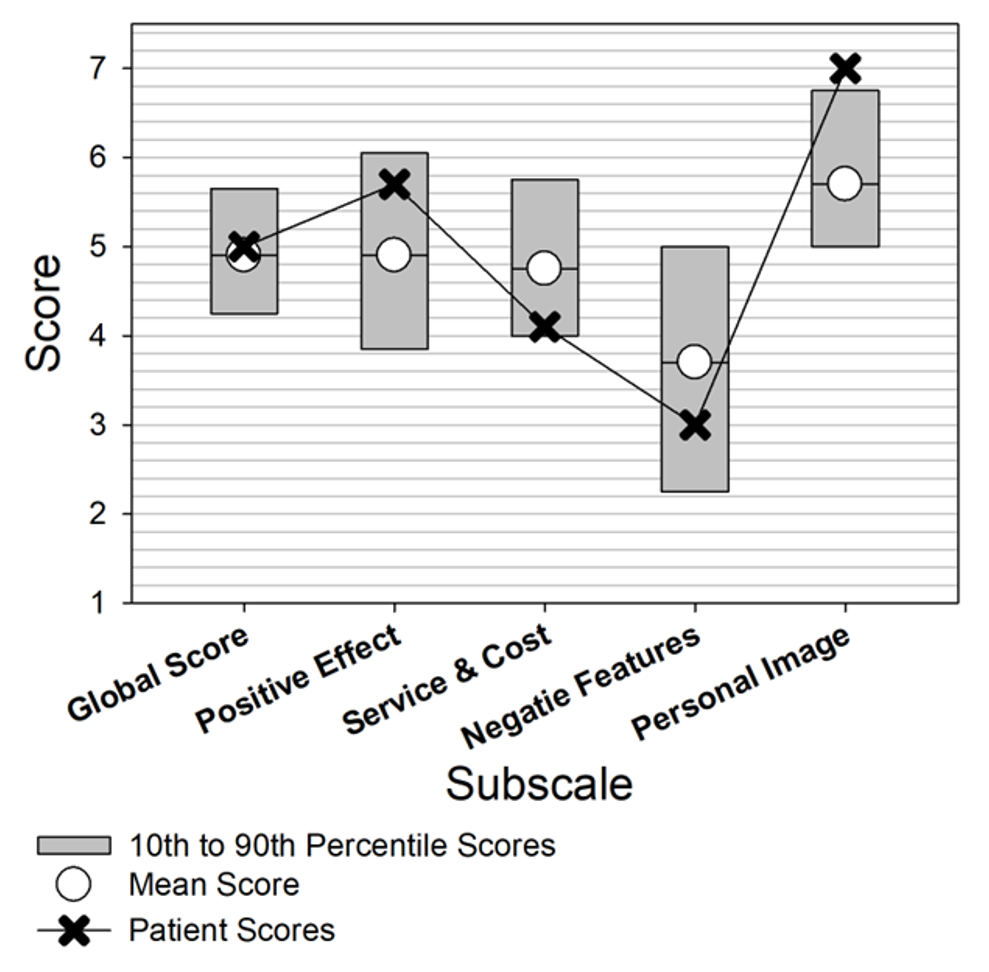

The scale is made up of 15 items. Each of the four subscales of the SADL covers a different aspect of satisfaction and was decided upon by interviewing many hearing aid users with at least one year of experience. The four subscales are: Positive Effect, Service & Cost, Negative Features, and Personal Image. All items are rated on a 7-category scale: Not At All, A Little, Somewhat, Medium, Considerably, Greatly, and Tremendously. A sample scoring template is shown in Figure 6, with ratings from a sample patient.

Figure 6. Scoring template for the SADL, with sample scores for a given patient.

17. Okay. We’ve now covered both benefit and satisfaction. That’s it?

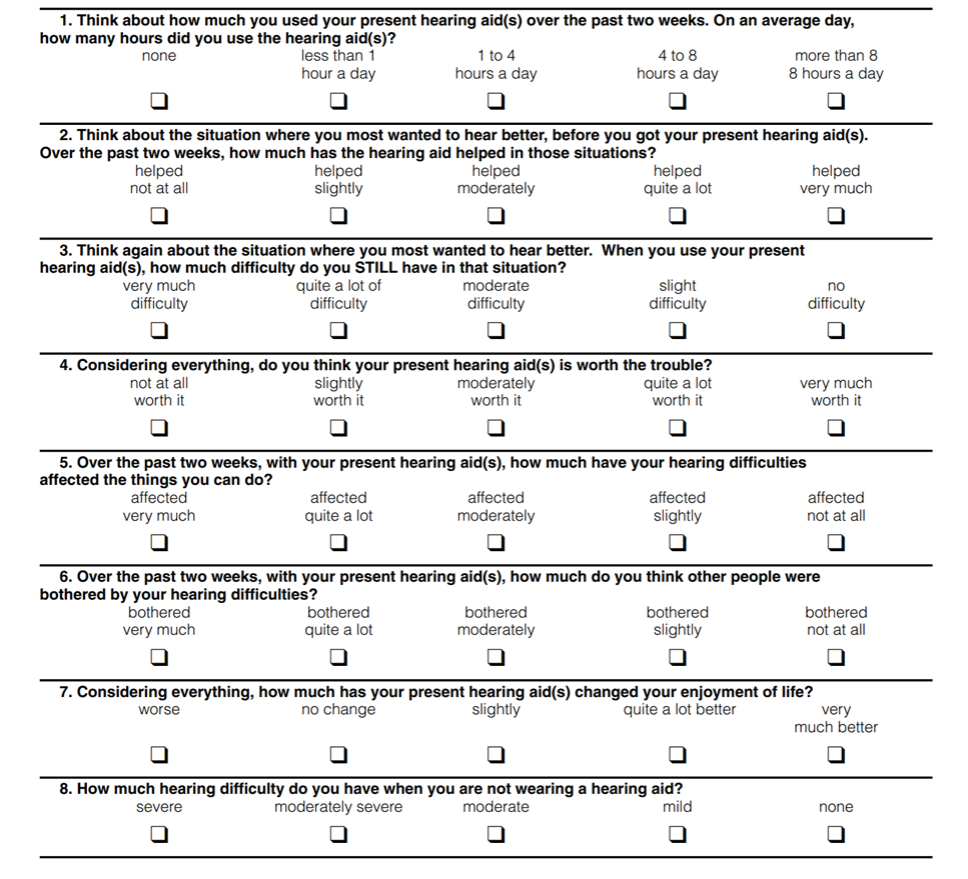

Not quite. There’s one more scale that’s just too good not to use. I briefly mentioned it back at the beginning of our conversation: the IOI-HA (Eye-Oh-Eye-Ha; Cox & Alexander, 2002, Cox et al., 2003a). I say “too good” because a) it’s short, b) easy to administer and score, c) it covers 7 different domains, d) it’s well-researched, and e) it’s been translated into 30 or so different languages. The English version is in Figure 7 (and Appendix). Question #8 is not domain related—this question is to determine which of the two scoring templates should be used—the norms are different for patients who report a mild-moderate hearing difficulty vs. those who report a moderate-severe, or severe problem.

Figure 7. The seven questions of the IOI-HA, covering seven different domains. Form includes Question #8, used for determining what normative values are used for interpretation of findings. Click here for an enlarged image.

Note that each of the first seven questions relate to a different domain. The domains are:

- Daily use

- Benefit

- Residual activity limitation

- Satisfaction with amplification

- Residual participation restriction

- Impact of using hearing aids on significant others

- Impact on quality of life

Each of the IOI-HA items has five answers that range from the worst outcome on the left to the best outcome on the right. Answer choices are equidistant in meaning in English. To score the outcome, each answer is given a number value 1 (worst) through 5 (best). The inventory was designed to be given in paper-and-pencil form, but is included in the HIMSA Noah Questionnaire Module, which is a convenient method to store the results.

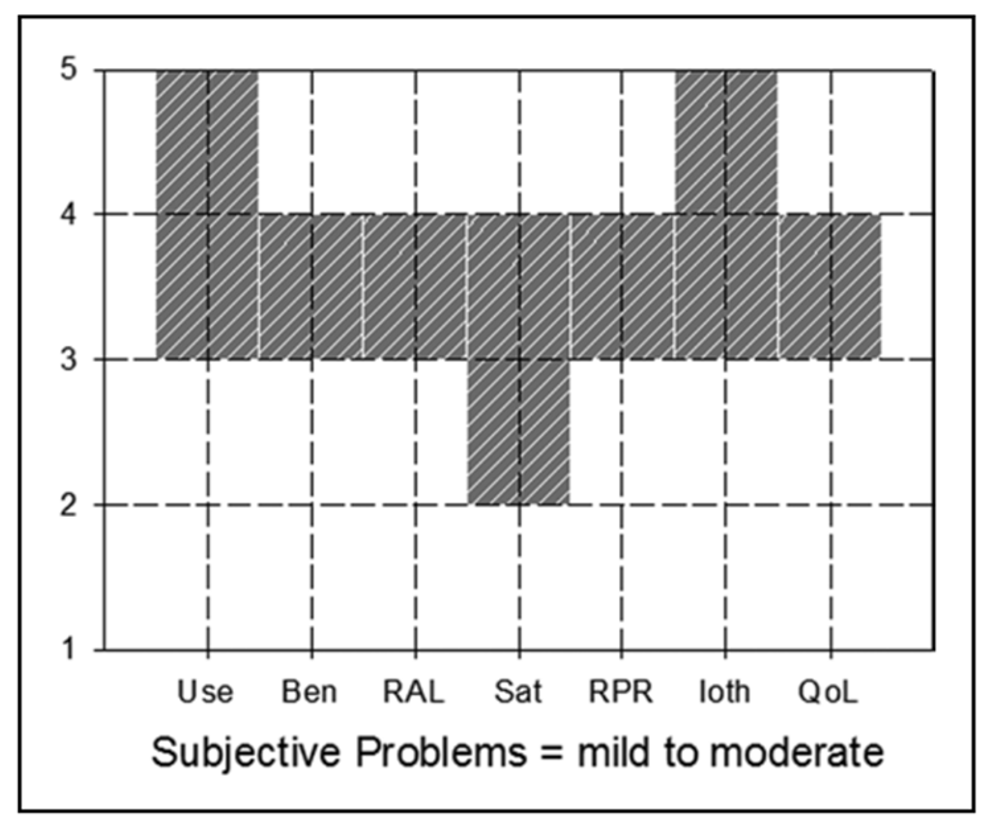

The IOI-HA can be used as a very quick way to evaluate patient outcomes to reinforce the positive impact of our clinical services, or identify areas that require post-fitting attention—either through device changes, programming adjustments, or counseling. Additionally, the IOI-HA can be useful for clinical comparisons across groups based on differences in clinical setting, treatment options, or specific clinicians. The standard scoring template for a single patient is shown in Figure 8. This template is for those who report mild or moderate hearing problems without amplification (based on the answer to Question #8); there is a different template for the patients who report moderately-severe or severe subjective problems.

Figure 8. IOI-HA scoring template for patients with reported mild-to-moderate hearing loss.

18. Not sure I’m understanding that scoring sheet. The response is “okay” if it falls anywhere within the shaded block?

That is correct. We’re normally, however, just looking at the extremes of the shaded area. Let’s take Benefit for example (“Ben” on the X-axis). The patient would be “within norms” if he or she gave you a “3” or “4” rating. A “5” rating would be great, a “2” rating, you need to have a talk. Now, you said “anywhere within the shaded box,” but recall that there is only one question for each domain, so you will never have a score such as 3.5, or 2.5, unless you’re averaging multiple tests from the same person, or doing some averages for a group of your patients.

The template was designed for minimal “clinician burden” for a single patient. If you want to obtain a little more detail, or are looking at averaged data (from several patients or providers), you might want to look at the actual normative means and standard deviations (see https://harlmemphis.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/5.pdf). For example, going back to the Benefit rating for patients who report mild-to-moderate problems, the mean for this domain is 3.39, with a standard deviation of .98; this would give you a range of 2.41 to 4.37.

19. I seem to reaching the end of my allowed questions. Back at the start of our conversation, you mentioned that are some new, or newer self-report inventories?

Right. Tell you what, I’ll simply do a listing of some of the newer ones of different domains, and also toss in a few of my favorite old ones too, ones that we didn’t get a chance to talk about. You can scan the list and see if there is anything that interests you.

- Domain=Expectations. Expected Consequences of Hearing Aid Ownership (ECHO; Cox and Alexander, 2000). Developed as a companion instrument to the SADL questionnaire, the satisfaction measure that I recommended earlier. As with the SADL, it produces a global score and four sub-scales: Positive Effect, Services & Cost, Negative Features, and Personal Image.

- Domain=Activity limitations. Speech, Spatial, Quality-12 (SSQ-12; Noble et al., 2013). The SSQ-12 is a shortened version of SSQ-49. The 12 questions cover a wide range of potential activity limitations such as: speech in noise, localization, distance and movement, sound quality, and listening effort. It is scored on a 11-point scale going from 0=Not at all, to 10=Perfectly. A screening version, the SSQ-5 also is available (Demeester et al., 2012).

- Domain=Benefit. Device Oriented Subjective Outcome (DOSO, as in Dough-So; Cox et al., 2014). Designed to measure the benefit of the device itself, and to be less sensitive to personality of the hearing aid user. The measure has six subscales: Speech Cues, Listening Effort, Pleasantness, Quietness, Convenience, and Use. All items (other than those for the Use subscale) are rated on a 7-category scale: Not At All, A Little, Somewhat, Medium, Considerably, Greatly, Tremendously.

- Domain=Loudness restoration. Profile of Aided Loudness (PAL; Mueller & Palmer, 1998, Ricketts et al., 2019). Designed to determine if the use of hearing aids restored loudness normalization, and a tool to monitor loudness acclimatization. Rating conducted for 12 everyday sounds, 4 each for soft, average and loud, based on normative data. Each item rated on 7-point loudness scale, 1=Very Soft to 7=Uncomfortably Loud.

- Domain=Empowerment. Brief Empowerment Questionnaire (Emp-AQ-5; Bennett et al., 2024). A 5-question scale that samples empowerment related to the patient’s hearing loss. Each statement is scored on a 4-point scale ranging from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. A 15-item scale also is available.

- Domain=Self-Esteem. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1965). This is a 10-item scale; 4-point Likert (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree), containing 5 positive and 5 negative items. While this time-honored scale is 60 years old, it remains the standard self-esteem measure, and has been used in recent hearing aid research (e.g., Ceyhan & Ture, 2023).

- Domain=Listening Effort. Effort Assessment Scale (EAS; Alhanbali et al., 2017). Participants are asked to rate their experience of listening effort on a daily basis. The total number of items in the EAS is 6. Responses are provided on a scale ranging from 0 to 10 (0=no effort, and 10=lots of effort).

- Domain=Listening Fatigue. Vanderbilt 10-Item Fatigue Scale for Adults (VFS-A 10; Hornsby et al., 2023). Patients respond to how often a given statement describes what they experience in a typical week. Each statement is scored on a five-point scale (0 to 4), ranging from Never/Almost-Never to Almost-Always/Always. There also are three pediatric versions of the Vanderbilt Fatigue Scales (the VFS-Peds)—a child self-report version (VFS-C), a parent proxy-report version (VFS-P), and a teacher proxy-report version (VFS-T).

20. A little overwhelming, but thanks for all the information. Any closing comments?

First, since you mentioned you’re not doing any self-assessment scales at the moment, I’d suggest that you at least start with the RHHI, COSI, and the IOI-HA—all three have low patient and clinician burden. Remember, both the COSI and the IOI-HA are included in the HIMSA Noah Questionnaire Module. Maybe once you become comfortable with these, you could add the other two that we discussed. I think you’ll like the extra information you’ll have regarding your hearing aid patients.

In the world of fitting hearing aids, we owe much of our understanding of the use of self-reports to Robyn Cox, who not only developed several scales, but taught many of us how the use them properly. I’ll end with one of her summary statements (Cox et al., 2003b):

“It is clear that self-reports of daily-life hearing problems are only partly rooted in physiological impairment and in the types of psychoacoustic abilities encompassed in traditional audiometric examinations. Self-reports provide unique insights into the consequences of hearing loss that are not obtainable with conventional objective clinical assessments.”

References

Alhanbali, S., Dawes, P., Lloyd, S., & Munro, K. (2017). Self-reported listening-related effort and fatigue in hearing-impaired adults. Ear and Hearing, 38(1), e39–e48. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e31824e0ba7

Bennett, R., Larsson, J., Gotowiec, S., & Ferguson, M. (2024). Refinement and validation of the Empowerment Audiology Questionnaire: Rasch analysis and traditional psychometric evaluation. Ear and Hearing, 45(3), 583–599.

Bentler, R., Mueller, H. G., & Ricketts, T. (2016). Modern hearing aids: Verification, outcome measures and follow-up. Plural Publishing.

Cassarly, C., Matthews, L., Simpson, A., & Dubno, J. (2020). The revised hearing handicap inventory and screening tool based on psychometric reevaluation of the hearing handicap inventories for the elderly and adults. Ear and Hearing, 41(1), 95–105.

Ceyhan, A., & Ture, L. (2023). Non-audiological and audiological factors as indicators of hearing aid satisfaction in adults. Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat, and Head & Neck Surgery, 31(2), 69–74.

Cox, R. M. (1997). Administration and application of the APHAB. The Hearing Journal, 50(4), 32–48.

Cox, R. M. (2005). Choosing a self-report measure for hearing aid fitting outcomes. Seminars in Hearing, 26(3), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-922236

Cox, R. M., & Alexander, G. C. (1995). The abbreviated profile of hearing aid benefit (APHAB). Ear and Hearing, 16(2), 176–186.

Cox, R. M., & Alexander, G. C. (1999). Measuring satisfaction with amplification in daily life: The SADL scale. Ear and Hearing, 20(4), 306–320.

Cox, R. M., & Alexander, G. C. (2000). Expectations about hearing aids and their relationship to fitting outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 11(7), 368–382.

Cox, R. M., & Alexander, G. C. (2002). The international outcome inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA): Psychometric properties of the English version. International Journal of Audiology, 41(1), 30–35.

Cox, R. M., Alexander, G. C., & Beyer, C. M. (2003a). Norms for the international outcome inventory for hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 14(8), 403–413.

Cox, R. M., Alexander, G. C., & Gray, G. (2003b). Audiometric correlates of the unaided APHAB. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 14(7), 361–371.

Cox, R. M., Alexander, G., & Xu, J. (2014). Development of the device oriented subjective outcome (DOSO) scale. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 25(8), 727–736.

Demeester, K., Topsakal, V., Hendrickx, J., Fransen, E., Van Laer, L., Van Camp, G., Van de Heyning, P., & Van Wieringen, A. (2012). Hearing disability measured by the speech, spatial, and qualities of hearing scale in clinically normal-hearing and hearing-impaired middle-aged persons, and disability screening by means of a reduced SSQ (the SSQ5). Ear and Hearing, 33(5), 615–626.

Dillon, H., James, A., & Ginis, J. (1997). The client oriented scale of improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 8(1), 27–43.

Hornsby, B., Camarata, S., Cho, S. J., Davis, H., McGarrigle, R., & Bess, F. (2023). Development and validation of a brief version of the Vanderbilt Fatigue Scale for Adults: The VFS-A-10. Ear and Hearing, 44(5), 1251–1261.

Humes, L. E. (2022). 20Q: Assessing auditory wellness in older adults. AudiologyOnline. Article 28087. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Mormer, E., & Palmer, C. (2001, April). Reliability of hearing aid expectation response [Presentation]. Annual conference of the American Academy of Audiology, San Diego, CA.

Mueller, H. G., & Palmer, C. (1998). The profile of aided loudness: A new "PAL" for 1998. The Hearing Journal, 51(1), 10–19.

Mueller, H. G., Bentler, R., & Ricketts, T. (2013). Modern hearing aids: Pre-fitting testing and selection considerations. Singular Publishing.

Mueller, H. G., Ricketts, T., & Bentler, R. (2017). Speech mapping and probe microphone measures. Singular Publishing.

Mueller, H. G., Coverstone, J., Galster, J., Jorgensen, L., & Picou, E. (2021). 20Q: The new hearing aid fitting standard - A roundtable discussion. AudiologyOnline. Article 27938. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Mueller, H. G., & Taylor, B. (2024). Research QuickTakes Volume 8: Hearing Aid Fitting Toolbox v2: Non-audiologic considerations in the selection and fitting of hearing aids. AudiologyOnline. Course #39883. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Noble, W., Jensen, N. S., Naylor, G., Bhullar, N., & Akeroyd, M. A. (2013). A short form of the speech, spatial, and qualities of hearing scale suitable for clinical use: The SSQ12. International Journal of Audiology, 52(6), 409–412.

Palmer, C. V., Solodar, H., Hurley, W., Byrne, D., & Williams, K. (2009). Self-perception of hearing ability as a strong predictor of hearing aid purchase. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 20(6), 341–347.

Ricketts, T., Bentler, R., & Mueller, H. G. (2019). Essentials of modern hearing aids. Singular Publishing.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01038-000

Weinstein, B. E. (1997). Introduction: Customer satisfaction with and benefit from hearing aids. Seminars in Hearing, 18(1), 3–5.

World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Available from www.who.int

Appendix

Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) - click here to view. Download from https://harlmemphis.org/

Client Oriented Scale of Improvement - click here to view. Download from https://www.nal.gov.au > NAL products

Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory - Screening (RHHI-S) - click here to view.

Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life - click here to view. Download from https://harlmemphis.org/

Citation

Mueller, H. G. (2025). 20Q: Hearing aid selection and fitting - The role of self-report inventories. AudiologyOnline, Article 29198. Available at www.audiologyonline.com