From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

There are a lot of people out there with significant hearing loss. Some of them choose to wear hearing aids, many do not. Why? A few of the reasons for this are easy to explain, but most of the factors are difficult to pigeonhole. When we compare hearing aid “adopters” to “non-adopters,” they often appear to be very similar people.

Over the years, the best source of information on this topic has been the MarkeTrak surveys. These surveys have been conducted under the guidance of the Hearing Industries Association (HIA) since 1989. Regarding hearing aid adoption, one of the more memorable MarkeTrak findings from the 1990s, was that only 35% of hearing-impaired non-adopters stated they would wear hearing aids, even if they were free and invisible! Let’s hope things have gotten better.

In the past four years, two MarkeTrak surveys have been conducted, labeled MarkeTrak10 and MarkeTrak2022. The findings from these have been disseminated somewhat differently than in the past, with the results of each survey being discussed in several related articles published together in special issues of Seminars in Hearing. An audiologist who has contributed to both of these publications, and written about recent findings related to hearing aid adoption, is Lindsay Jorgensen. She has agreed to share her insights here at 20Q.

Dr. Jorgensen, AuD, PhD, is an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Communication Disorders at the University of South Dakota, where she teaches, conducts research, and provides clinical services in the area of hearing aids and hearing assistive technology. Her research focuses on how to best personalize hearing technologies for the individual patient’s cognitive, psychological, physical, and social needs.

She is an Editorial Board member for Seminars in Hearing, and has served on many professional committees including the Board of Directors for the Academy of Audiology. She was recently honored for her research accomplishments with the University of South Dakota President’s Research Award.

Dr. Jorgensen is one of the founders of the Audiology Practice Standards Organization (APSO) and was a key contributor to standard S2.1 Hearing Aid Fitting for Adult & Geriatric Patients, published in May of 2021, which we reviewed in a previous 20Q. Don’t be surprised to find her at our Academy meetings, standing next to probe-mic equipment, willing to show most any passerby the nuances and pleasures of hearing aid verification.

Before we get to verification, however, we need to understand our patients, why some are eager hearing aid users and others are not, and how we can turn “non-adopters” into successful hearing aid users. You’ll find many of the answers in this month’s excellent 20Q by Lindsey.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Hearing Aid Adoption — What MarkeTrak Surveys Are Telling Us

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Describe the difference between a hearing aid adopter and non-adopter.

- Describe an opportunity for new or expanded patient population.

- Describe how an HHP can use the information from this article to expand their practice.

1. With everything surrounding OTCs, I have become more interested in hearing aid adoption. I hear that you’ve been doing some writing on that topic?

I have. I’ve recently written some articles for Seminars in Hearing on the topic, based on data from MarkeTrak 10 and MarkeTrak 2022 (Jorgensen & Barrett, 2022; Jorgensen & Novak, 2020). MarkeTrak 10 was collected in 2019 and published in 2020. In case you haven’t been following the MarkeTrak surveys, they have been conducted under the guidance of the Hearing Industries Association (HIA) since 1989. They were originally labeled with Roman numerals (e.g., MarkeTrak VIII was the last with such labeling) and then labeled with numbers (i.e., MarkeTrak 9 and MarkeTrak 10). They are now labeled based on the year that the survey was conducted—hence, MarkeTrak 2022. This makes good sense, as now we know the general time frame of the data, which we didn’t do with the other labeling.

2. You covered all of the data collected in the MarkeTrak 10 and 2022? What did these surveys have in common?

First, I didn’t cover all the data! There is so much amazing information in these surveys that it filled two full editions of Seminars in Hearing. I only looked at the data on hearing aid adoption—as in, who we see, how they get to us, and what factors relate to their adoption. There are many other articles in Seminars based on these surveys that looked at benefit and satisfaction, financing, diversity, cochlear implant use, and a variety of other interesting topics. Additionally, Kate Carr from the HIA also did an excellent review of MarkeTrak 10 in a 20Q article in 2020 (Carr, 2020).

In MarkeTrak 10 (MT10), I discussed how our patients get to us, when do they decide to come in, and who refers them. Once they get to us, what makes them decide to adopt technology, or not? Then in MarkeTrak 2022 (MT2022), I looked at how we could use these data to better define our patients and identify opportunities for new patients.

3. You say that these surveys have been going on for over 30 years. Have our hearing aid patients changed?

As we know, hearing loss increases as we age and data from both MT10 and MT2022 continue to support this statement. We also know that men report higher rates of hearing loss than women, which is consistent with previous reports, and I would guess, consistent with the experiences of most clinicians. In line with previous MarketTrak reports, the majority of those with self-reported hearing loss are over the age of 65. Non-owners are younger than owners and the current age of hearing aid owners continues to be around 66 years of age. Our patients are living longer, and that gives us the opportunity to have them as patients for many years to come. On average, people report that they are purchasing their first set of hearing aids at 58 years old.

Even better news is that we often think of our current patients as the best resource for new hearing aid purchases, the MarkeTrak data suggests that most people who are on their first or second set of hearing aids, plan on purchasing another set.

4. Earlier, you mentioned non-owners, what do we know about them?

Well, it depends on which non-owners we are talking about—those who admit they have hearing loss or those who maybe “know,” but don’t really want to admit it. As I mentioned earlier, non-owners are slightly younger than people who have purchased hearing aids.

Overall, respondents on the MT10 survey reported that they have had hearing loss for 12 years. But comparing those who own hearing aids to those who are non-owners may shed some light on the people who are not ready to obtain hearing aids. Those who have hearing aids report they have had hearing loss longer (14.6 years) than those who do not have hearing aids (10.5 years). This is where we don’t really have all of the necessary background data. Hearing aid owners reported that they had noticed hearing loss for 6.7 years prior to getting aids; a three-year shorter period than what non-owners are reporting (10.5 years). It is interesting to consider why this difference might exist? Accessibility? Affordability? Personality differences? Maybe those in the non-owner group are potential over-the-counter hearing aid users?

5. Is there something about a person that can predict if they will purchase a hearing aid?

As all clinicians would agree, people report that speech understanding in background noise continues to be their primary reason to think that they have hearing difficulty, and often is the reason why they go to see a professional. Out of the top six reasons that people report they have difficulty hearing, most were related to not being able to hear in noise.

- I have trouble hearing conversations in a noisy background

- Family members and friends have told me they think I may have hearing loss

- I have trouble following conversations when 2+ people are talking

- I have trouble understanding things on the TV

- I have trouble understanding the speaker in a large room

- I get confused about where sounds come from

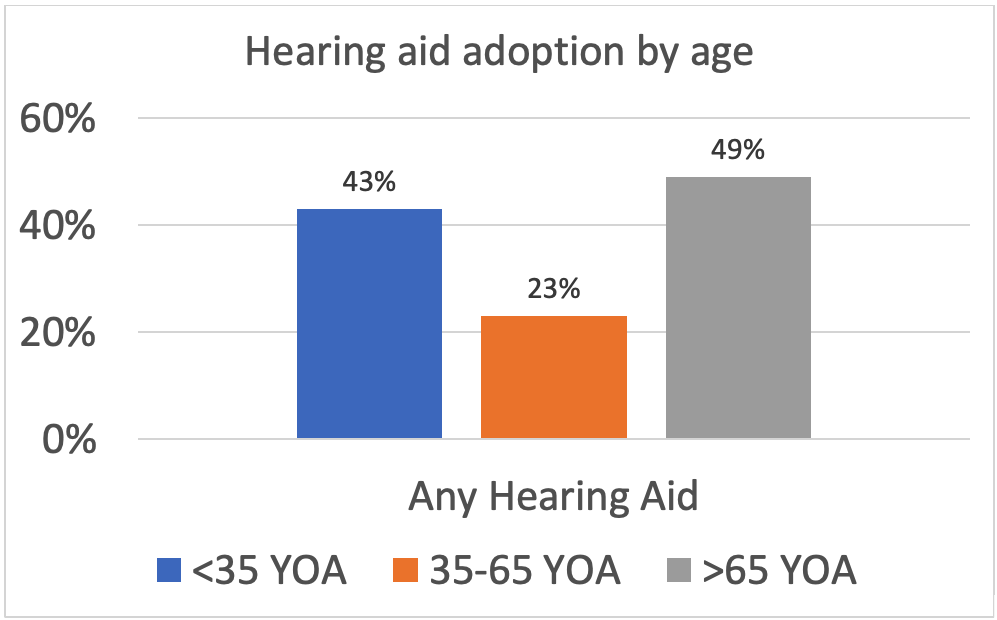

Data on hearing losses suggest that 314 in 1000 people over 65, and roughly 40-50% of people over 75 have hearing loss. For younger ages, it is estimated that 1/6 baby boomers (14.6%) and 1/14 Gen Xers (7.4%) already have hearing loss. But we don’t see the same trend with purchase. When looking at hearing aid adoption rate by age, younger people, under 35, actually purchase aids at a higher rate than middle aged people 35-64. It is an interesting trend that was investigated further in MT2022.

6. That does seem like a strange U-shaped curve of adoption. Do you have any thoughts on that?

You know, we were puzzled by this as well. Initially in MT10 we thought it was interesting. After seeing the same trends in MT2022, we decided to take a hard look at it. We could easily explain why the older adults obtained hearing aids more often than younger adults, as they have more hearing loss, as has been shown in previous MarkeTrak surveys, there is less stigma for this group. But, we found it a little strange that the younger people obtained hearing aids more often than the middle age range (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hearing aid adoption from MarkeTrak 2022 data. This data suggest a U-shaped adoption pattern where younger people are obtaining hearing aids at a higher rate than middle-aged people. Percentages are based on individuals who self-reported that they have a hearing loss.

Initially, we thought that maybe those in the middle range, age 35 to 64, believed that they are too young to obtain hearing aids, which could be related to negative images and the stigma of hearing loss. It is also possible that younger individuals may be more likely to be influenced by the adults and educators in their lives. But as we thought about it more, we remembered that EHDI really took off in the early 2000s when those under 35 were infants and school-aged children (White et al 2010). It is possible that those who were younger were those that the EHDI program identified these individuals younger and allowed for early intervention including the use of hearing aids. Therefore, we think that one of the partial explanations for the increased rates of younger adults obtaining hearing aids is that they had them as kids because they were identified much younger. If we think about it, some of the first children to be implanted with a cochlear implant have still not yet reached the age of 35.

7. This can’t just be that we are better at identifying. Don’t we have better technology and counseling?

Absolutely, we are better able to fit a variety of hearing losses, including mild to moderate hearing losses as hearing technology has improved. Further, we are better at knowing that kids with unilateral hearing losses need hearing aids and we know how to better fit them (Benchetrit et al., 2022; Briggs et al., 2011). On the topic of counseling, we are getting into schools with programs like Dangerous Decibels (www.dangerousdecibels.org). That may move the needle somewhat as well. It is also possible that there is an effect of noise-induced hearing loss. With the increase of ear-level listening devices, some studies have suggested an increase in hearing loss (Basjo et al., 2016). And of course, we can’t forget all the people who have served in the military, many in combat—a large group of these are under the age of 35.

I guess it probably is a combination of better identification, better fitting ability, and better counseling/knowledge of hearing loss that could be driving the increase in hearing aid use in the younger generation. Whatever the reasons, I think that the trends suggest that there will be more hearing aid users in the future.

8. More users may be coming our way, but who are our current patients?

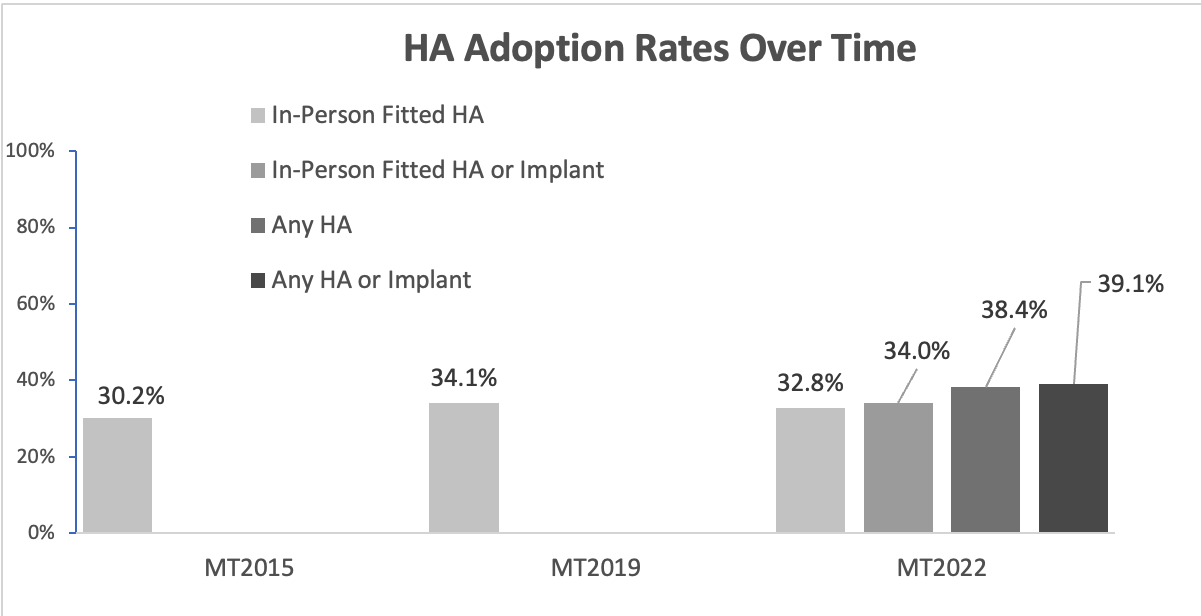

As you can probably predict based on our previous data, age is the best predictor of hearing aid adoption; those that are older are more likely to pursue amplification. Not surprisingly, those who report higher rates of hearing loss are more likely to obtain hearing aids as long as they are bothered by it. It is encouraging that the rate of hearing aid adoption is steadily increasing over time from 30.2% in the 2015 MT9 data, to 34.1% in the MT10 survey (Abrams & Kihm, 2015). In MT2022, we were able to break it down a bit more to look at type of device (See Figure 2). To compare data across the years, it would likely be most comparable to look at the MT2022 data to In-Person Fitted HA or Any HA to the MT10 (2019) and MT 2015. However, when you add in the PSAP or any device that the person deems as hearing technology, the usage increases to 38.4%.

Figure 2. HA adoption rates over time.

9. Previously, you mentioned stigma and negative images as a reason that people may not obtain hearing aids. Is this still the case?

Actually, we found the opposite. Respondents reported that the hearing aids rarely make them feel embarrassed. I was also pleasantly surprised when the MT2022 data suggested that people with untreated hearing loss reported that their hearing loss made them embarrassed at times. I guess once they get embarrassed enough, they decide it is time to come in, and they do. Hopefully we will see a trend down regarding the number of years it takes to obtain amplification.

10. A person knows they have hearing loss, they decide they are old enough and embarrassed enough, so why still the small percentage that actually follow through?

There are some of the MarkeTrak data that suggest that third-party payers could be a factor. There are two ways to look at this. First, we could ask people who didn’t obtain hearing aids if they would if their insurance covered it. We are seeing more and more third-party providers that cover all or some of the cost of hearing aids. Now I will note that in our clinic at the University of South Dakota we itemize bundle, as do many other clinics, which can cause some interpretation concerns in this area, but that is for another discussion.

The MT10 asked respondents, using a 5-point Likert scale, what their likelihood of obtaining a hearing aid if they had an insurance policy that covered the aids. The data are very interesting. If the coverage was $500 or $1000, about 1/3 of the people reported that they definitely or probably would purchase, and 1/3 of the people reported that they definitely or probably would not. This is interesting because it is pretty much in line with the data of people that do or do not get hearing aids in general. This suggests to me, that people are not highly influenced by what the insurance will pay. However, once you ask if the participants how they would react if insurance covered the total cost of the hearing aids, 54% of people reported that they “definitely or probably” would purchase hearing aids while the “definitely or probably not” decreased to 18%. It appears that more people would obtain hearing aids if insurance covered them completely.

But there is a second way to look at this question. There are places where people can obtain their hearing aids for free, like the VA, or they have access to a national healthcare system that covers hearing aids.

There are several EuroTrak surveys that we can look to for this answer, where most people surveyed reported that hearing aid access was part of their national healthcare plan. There is a small 7% difference in the rates of obtaining hearing aids between the MarkeTrak (34.1%) the 2018 European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association (EHIMA) EuroTrak UK respondents (41.6%) (European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association [EHIMA], 2018a). It is not as much of a difference as I would expect.

Looking back at our non-owners who report a significant hearing loss, and think they should be amplified, they are slightly older, have less college education, and are less likely to be retired than those who are non-owners who report less hearing loss. I think those are the people that could most benefit from some form of hearing aid insurance coverage or programs that help pay for the cost of the hearing aids.

11. It seems that people just want to wait a while to take action after they know they have a hearing loss?

Yes, that is still the trend. People report that at about four years after they start noticing hearing loss, they talk with their primary healthcare provider about it, and usually get a referral to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) physician and/or obtain a hearing test. Some initially go to a hearing healthcare provider—audiologist or hearing instrument specialist. After about 6 years, patients report that they obtain their first set of hearing aids and then are fitted with their second set at about 11 years after they first start noticing hearing loss. On average, people wait about one and one-half years from when they have a hearing test to when they obtain their first set of hearing aids.

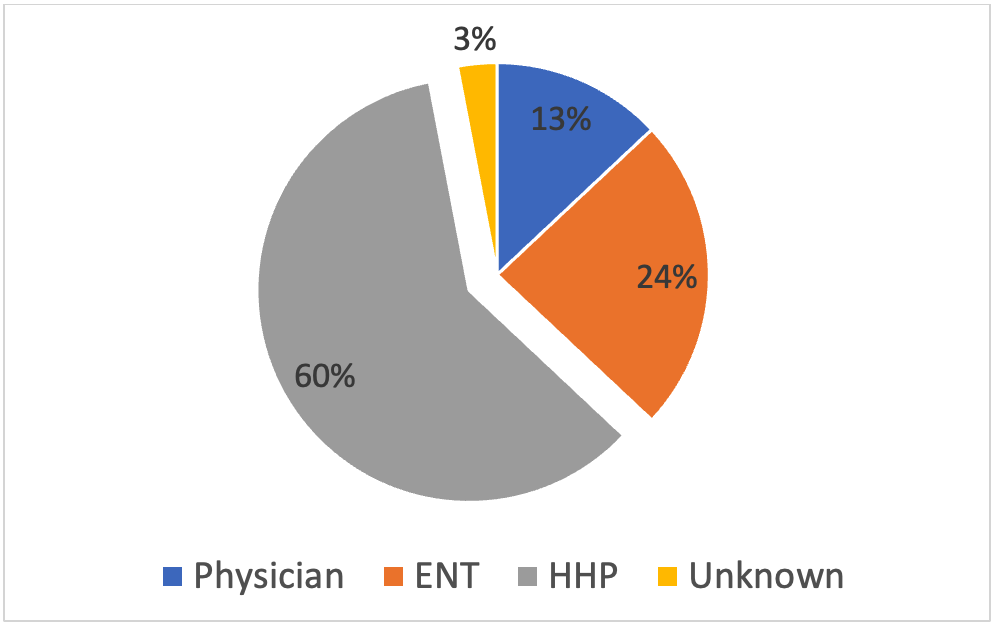

We were able to look further into these data to examine where they obtained their information. Was it from their primary care provider, an ENT physician, or a hearing healthcare provider (HHP). As shown in Figure 3, it is nice to know that 60% of those with reported hearing loss first went to an HHP. Thirty-seven percent reported they either went to an ENT physician (24%) or an undetermined type of physician (13%). Those with hearing loss are overwhelmingly first going to an HHP.

Figure 3. Type of professional that was the point of first professional contact for a person with suspected hearing loss.

12. That is good to hear. Do you know how they found their hearing healthcare provider?

We don’t have those data regarding the initial hearing test, but we do for the hearing aid purchase. MT10 suggests that more than half (52%) of those who bought hearing aids were referred to their HHP by a friend. On the other hand, 53% of non-purchasers reported that their spouse was the one that chose the provider, but only 25% of purchasers reported this. This suggests to me that the motivation for making the appointment is still the top driver to purchase hearing aids. Once there, 68% of respondents reported that their only reason for going to the facility was to purchase hearing aids, and patients were most likely to go to a private practice to obtain their devices (54%). Most respondents identified their HHP as an audiologist. But I still find it interesting that there appears to be that lag of 1.6 years between getting tested and when they actually purchase the devices.

And, where things get a bit more interesting are these findings:

- Of those who first went to a non-ENT physician, 17% were confirmed to have hearing loss, but only 12% were recommended that they do something about it, like get hearing aids. And of those 12%, only 7% actually did.

- Of those who first went to an ENT physician, 21% were confirmed to have hearing loss, but only 12% were recommended that they do something about it, like get hearing aids. And of those 12% only 9% actually did.

- Those who went to a HHP, 52% were confirmed to have a hearing loss, but only 41% were recommended action. Only 34% actually did.

13. I think we really need to listen to patient concerns, which often is speech understanding in background noise. Did the survey examine if speech-in-noise testing is being conducted.?

All the respondents reported obtaining a traditional hearing test; 64% of them reported receiving a speech-in-noise test. A rather surprising finding, as this is much higher than what has been shown when HHPs have been surveyed (Mueller et al, 2010). Of course, we’d like this value to be near 100%.

On a positive note, 94% reported they were happy with how the hearing test was explained to them and 89% reported that the HHP addressed their specific needs. The respondents were, in general, very satisfied with their HHP. Ninety-four percent of hearing aid owners reported overall satisfaction. Even 83% of non-owners reported satisfaction with their HHP.

14. If a large portion of HHPs are not doing the tests to demonstrate the patient’s speech-in-noise concerns, what are patients happy about?

People reported that they were the most satisfied with the professionalism and quality of service that their HHP provided. Participants were least satisfied with the selection of hearing aids and the purchase policies. I believe this relates back to bundling the services with the cost of the hearing aids. Patients are becoming more savvy as to the cost of hearing aids. I believe we need to demonstrate our professionalism and the costs of our services. Audiologists should be transparent about the hearing aids that they recommend and provide; they should demonstrate why a patient needs a specific device and why that device was recommended. Being transparent about purchase policies seems to go a long way for our patients. I guess it all comes down to trust.

Patients report that they listen to our recommendations if we do recommend hearing aids, but for those who did not obtain a hearing aid, 46% reported that they were told by the HCP to hold off on the purchase—a much higher number than I would expect. Even 11% of owners reported that they were told to wait as well.

But back to your question, most people reported that the HHP addressed their questions, but it was much higher for those who bought hearing aids: 94% vs. 81% of non-owners. Yes, I guess it does matter if your patients feel like you heard them. And even more drastically, 90% of owners reported that their HHP considered their abilities and needs when suggesting a specific hearing aid where only 60% of non-owners reported that their needs were considered. More owners believed that their appointment with the HHP was personal and friendly, while non-owners reported that the appointment felt sterile and that the HHP was focusing more on the sale of the product. Owners reported that the HHP makes them feel welcome and that the focus was rehabilitation and not device driven. But this is not new information. There have been several previous studies that suggest that having a welcoming and friendly environment does make a patient more likely to purchase hearing aids.

15. Circling back to some of the earlier data you reported, our primary demographic is still older men who have had hearing loss for quite a few years and are recommended to the HHP by their friends?

Sort of, yes. For many years it has been suggested that gender and hearing difficulty are the best predictors on whether someone pursues amplification. Men are more likely to have hearing loss (12.8%) than women (8.9%). When comparing the rate of hearing aid adoption between men and women, the MarkeTrak data continues to suggest that ~40% of both men and women report that they have purchased hearing devices.

I do find this latter trend interesting. Audiologists see more men than women, the degree of hearing loss in men is greater, but women are buying hearing aids at the same rate. Meaning women are just as likely to obtain hearing aids even though they may have slightly better hearing. This does follow national data suggesting that women are more likely to seek out healthcare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Center for Health Statistics, 2001) suggests that younger women are 33% more likely to visit a doctor than men, although this difference decreases with age.

16. That leads me to the next question, what can we do to increase the number of patients that walk through the door? Where are the opportunities? What assumptions can we make with these data to impact our future directions?

You know, that is really one of the main things addressed in the MT2022 survey. We tried to use these data to help us look at where audiologists could expand their practice and increase opportunities to help people with hearing difficulties.

We did talk a bit earlier about age and that interesting U-shaped trend. While aging patients are still the most common patients who come to an HHP, there does remain an opportunity for us to engage with those in the middle age range. Additionally, it is possible that we could engage more with the younger people to ensure that they continue to use amplification as they age. Again, I think that it is possible that our demographic will continue to change, but HHPs need to put some work into the middle-aged people. Many of them walk around with things in their ears, why not add hearing aids to that list?

Maybe it is because we are attracting younger patients, that we are seeing a trend of more people reporting that their hearing loss is due to noise exposure as opposed to age. It is also possible that we are more aware of noise exposure than we have been in the past—and it is not just military service. Either way, it may be worth audiologists leaning into this trend. Most of our advertisements have focused around making hearing aids appear as not just a device for the old – but linking it to noise exposure and alongside hearing protection may be a way to increase patient knowledge. The goal would be to attract younger patients who may be noticing the effects of hearing loss on their occupational, social, and educational endeavors. We also could increase the marketing efforts to include the impact of hearing loss, such on things that worry younger people: working memory and mental health. This could encourage those patients to seek a solution earlier. And, of course, a routine speech-in-noise test also would be very appropriate for these patients during their clinic visit.

17. Are these things that we have been talking about and trying for years? What is new?

In the MT2022, we also looked at race. On average, people who reported themselves as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) reported lower rates of hearing loss than those who identify as white. Specifically, those who identify as Black and Hispanic report proportionately lower rates of hearing loss (5%, 8%), while Native American respondents report similar rates to White respondents (12%). There were a few thoughts as to why this could be. First, it’s simply possible that this group has less hearing loss or maybe are less often diagnosed. A 2019 report suggested that Black Americans spend more of their money on healthcare than White Americans (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019). It is possible that Black respondents are not as focused on hearing loss as they are focused on other medical conditions. It is also possible that Black respondents really do have less hearing loss – there are some data to suggest this (Bishop et al., (2019).

We also know, however, many people report that they have a hearing loss simply because they have been told this by a medial professional. It is also possible that BIPOC respondents don’t have a diagnosis of hearing loss because they don’t have access to an audiologist. Access to healthcare continues to be a problem for BIPOC families (Taylor, 2019), along with trust in the medical community (Kennedy et al., 2007). In general, patients like to go to a healthcare provider that they can relate to, trust, and have easy access to. BIPOC patients are more likely to see healthcare providers at places where BIPOC work (Alsan et al., 2019). As a profession, we can continue to expand services by hiring those who are BIPOC. Further, we could expand our cultural competency to provide adequate healthcare to patients who are from a variety of backgrounds. Understanding cultures, beliefs, and values can increase our patients and patient access through gained trust. Given that people who identify as BIPOC don’t report the degree of hearing loss that we would expect, this is definitely an area of opportunity for HHPs.

18. You’ve mentioned patient trust a few times throughout this conversation. Does trust in the provider continue to be a primary predictor of hearing aid purchase?

Yes, and it goes beyond the provider. As we’ve already discussed, patients are more likely to purchase hearing aids from a provider recommended by their friends and, many (39%) don’t even do any research on the provider, they simply go just based on their friends’ recommendations. This draws even more attention to the importance of the hearing healthcare experience. Patients report that the first contact with the clinic is just as important as the rest of their experience—so hire a quality front office team! It highlights the importance of personal connection with our patients, and it continues to be the trend that our current patients are our best referrals.

19. You keep mentioning that we need to market. How can we do this better?

Social media. More people find out information on social media than the traditional newspaper or billboard marketing. There are many to choose from: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, Google+ ,etc. Facebook continues to be the most commonly reported social media outlet, along with Instagram. Interestingly, Facebook is more common for traditional hearing aid owners, while Instagram was more popular for personal sound amplification products (PSAP) purchasers. This probably is due to age. Either way, I would suggest looking at Meta for posting your information simultaneously on several social media platforms. So maintain an attractive office page, keep it current and provide information, not just marketing. The information drives the trust.

20. The whole marketing thing gets me thinking back to OTC hearing aids. What do we know, or maybe conjecture, about their use and influence on market penetration and hearing aid dispensing in general?

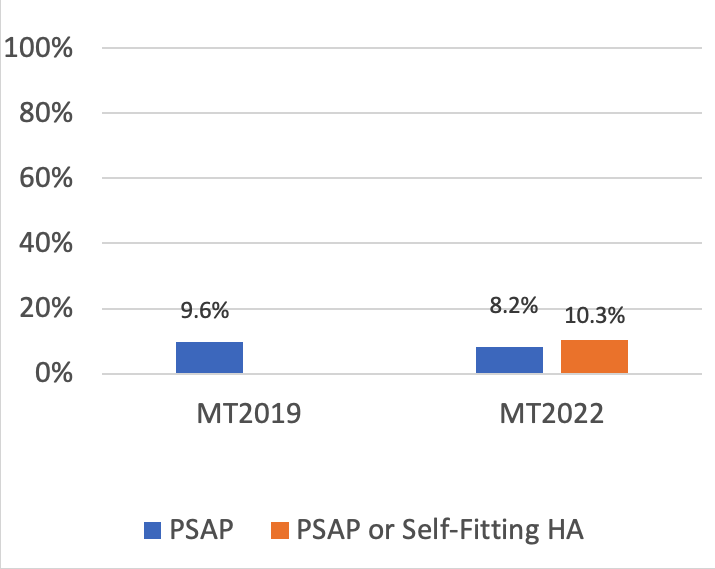

The data I’ve been discussing from the MarkeTrak surveys was collected prior to over the counter (OTC) hearing aids being approved by the FDA, but there are quite a few things that we can discus. PSAPs have been available for a number of years, and have some similarities with the new OTC category. Interestingly, when looking at PSAP devices, MT2022 did not show much difference from MT10 (2019) (see Figure 4). It will be interesting to see if there is any change when we survey OTC hearing aids.

Figure 4. PSAP rates over time. Percent of this category for total adoption rate for respondents who report that they have a hearing loss—represents ~4% of total adoption rate.

Some HHPs expressed concern that these products would replace traditional hearing aids. Many PSAPs are quite similar to the OTC hearing aids that are now available, so we can take the data from MT2022 and combine it with other data like JapanTrak, where questions regarding PSAPs and OTCs were included.

In Japan, OTC hearing aids have been available for over a decade. Data from the 2018 JapanTrak (EHIMA, 2018b) revealed that devices fit by an HHP had a much higher satisfaction than with those that were purchased over the counter. Further, the devices fit by the HHP were deemed to be overwhelmingly more reliable – ~80% vs ~25%! Patients who were fitted by an HHP wore their hearing aids 8.1 hours per day compared to only 4.9 hours per day by those who obtained OTC aids.

The data from Japan is consistent with the MT2022 results regarding PSAPs (the PSAP devices were, at the time of the survey, the only devices available direct to consumer). Hearing aid purchasers wore their hearing aids daily (63%) while only 46% of PSAP users reported using them daily. However, it could be that the PSAPs are being used by those with less significant hearing loss than those with traditional hearing aids. In fact, average MT2022 hearing aid owners reported that their hearing loss was moderate-to-severe, while PSAP owners classified their hearing loss as mild-to-moderate. Hearing aid owners also are much more satisfied with their hearing aid’s ability to help them in noise compared with those using PSAPs—another win for prescription-fit devices—we of course don’t really know if it’s the technology itself, or the proper fitting of the technology. I am curious as to how these data will change, if at all, with HHP compared to self-fit OTC hearing aids.

Not surprisingly, the surveys showed that PSAP owners were more likely first-time ”hearing aid” wearers, and reported a more mild hearing loss than those who had traditional hearing aids. They also reported more hearing loss than the non-owners.

These data remind me of the research findings I’ve often heard audiologist Catherine Palmer mention (Palmer et al., 2009). They asked a large group of potential hearing aid users to rate how much hearing difficulty they had, and then looked at their subsequent actions regarding pursing amplification. They found that people who rated their hearing as more troublesome (ratings of 8,9,10) were very likely to pursue amplification and people who rated their hearing as very good (1,2,3) were unlikely to pursue traditional amplification. The study suggested that we put our focus on those in the middle for counseling toward hearing aids. Additionally, these people came into the clinic knowing they had a problem, but OTC aids were not available. When thinking about these data today, however, we can relate it to those who may now pursue or be recommended for an OTC option. That is, those who report some difficulty with hearing, but not enough that it warrants the purchase of traditional hearing aids. Additionally, from MT 2022, 9/10 respondents reported that if they had purchased hearing aids in the past, they are still hearing aid owners today, while only 6/10 PSAP owners reported that they were still PSAP owners. PSAP owners could have moved on to hearing aids, or not using a device at all.

This is definitely an area of opportunity for audiologists. HHPs can complete the hearing evaluation, including a speech-in-noise test, and recommend the most appropriate device. In this regard, it’s important to note that our MarkeTrak survey showed that patients who owned hearing aids reported much more unaided difficulty following conversations in background noise than the non-owners. Based on the audiologic testing, the recommendation may be an OTC device, or it may be a traditional hearing aid. In the end, it is back to the patient’s trust in the HHP and that we represent the services we provide, not just the widget.

References

Abram, H., & Kihm, J. (2015). MT9 revealed renewed encouragement as well as obstacles for consumers with hearing loss. Hearing Review, 22(6), 16.

Alsan, M., Garrick, O., & Graziani, G. (2019). Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland. American Economic Review, 109(12), 4071-4111.

Basjo, S., Moller, C., Widen, S., Jutengren, G., & Kahari, K. (2016). Hearing thresholds, tinnitus, and headphone listening habits in nine-year-old children. International Journal of Audiology, 55(10), 587-596.

Benchetrit, L., Stenerson, M., Ronner, E., Leonard, H., August, H., Stiles, D., Levesque, P., Kenna, M., Anne, S., & Cohen, M. (2022). Hearing aid use in children with unilateral hearing loss: a randomized crossover clinical trial. Laryngoscope, 132(4), 881-888.

Bishop, C., Spankovich, C., Lin, F., Seals, S., Su, D., Valle, K., & Schweinfurth, J. (2019). Audiologic profile of the Jackson hearth study cohort and comparison to other cohorts. Laryngoscope, 129, 2391-2397.

Briggs, L., Davidson, L., & Lieu, J. (2011). Outcomes of conventional amplification for pediatric unilateral hearing loss. Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, 120(7), 448-454.

Carr, K. (2020). 20Q: Consumer insights on hearing aids, PSAPs, OTC devices, and more from MarkeTrak 10. AudiologyOnline, Article 26648. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association. (2018a). EuroTrak UK 2018. Anovum. https://www.ehima.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EuroTrak_2018_UK.pdf

European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association. (2018b). JapanTrak 2018. Anovum. https://ehima.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/JAPAN_Trak18.pdf

Jorgensen, L., & Barrett, R. (2022). Relating factors and trending in hearing device adoption rates to opportunities for hearing healthcare providers. Seminars in Hearing, 43(04), 289-300.

Jorgensen, L., & Novak, M. (2020). Factors influencing hearing adoption. Seminars in Hearing, 41(01), 006-020.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2019, February 21). The real cost of health care: Interactive calculator estimates both direct and hidden household spending [Press release]. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/press-release/interactive-calculator-estimates-both-direct-and-hidden-household-spending/

Kennedy, B. R., Mathis, C. C., & Woods, A. K. (2007). African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 14(02), 56-60.

Mueller, H. G., Johnson, E., & Weber, J. (2010). Fitting hearing aids: A comparison of three pre-fitting speech tests. AudiologyOnline, Article 861. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

National Center for Health Statistics. (2001, July 26). Women more likely than men to visit the doctor, more likely to have annual exams [Press release]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/01news/newstudy.htm#print

Palmer, C., Solodar, H., Hurley, W., Byrne, D., & Williams, K. (2009). Self-perception of hearing ability as a strong predictor of hearing aid purchase. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 20, 341-347.

Taylor, J. (2019). Racism, inequality, and health care for African Americans. The Century Foundation. Retrieved from https://tcf.org/content/report/racism-inequality-health-care-african-americans/

White, K., Forsman, I., Eichwald, J., & Munoz, K. (2010). The evolution of early hearing detection and intervention programs in the United States. Seminars in Perinatology, 34(2), 170-179.

Citation

Jorgensen, L. E. (2023). 20Q: Hearing aid adoption — what MarkeTrak surveys are telling us. AudiologyOnline, Article 28500. Available at www.audiologyonline.com