From the desk of Gus Mueller

From the desk of Gus Mueller

We’re back for another month talking about the relationship between what we eat and how we hear. Fascinating topic. I don’t know about you, but my hair cells are thanking me for my recent dinner of salmon, oysters, broccoli and nuts, with some bananas and dark chocolate thrown in for dessert. And of course, an ample supply of resveratrol to wash it all down.

If you recall, last month our 20Q guest author Chris Spankovich reviewed some of the animal studies related to diet and hearing. As our conversation was ending, we had moved on to humans, and were talking about the Healthy Eating Index (HEI). This is a measure of diet quality that assesses conformance to federal dietary guidance. The HEI component and overall scores are from dietary recall interviews collected during the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). General findings from HEI studies indicate that only about 10% of us have a “good” diet. Our intake of “meats and beans” seems to be quite adequate, but—here’s a shocker—we seem to be lacking in categories like “dark green and orange vegetables.” And yes, men are somewhat worse than women in most all categories.

If you recall, last month our 20Q guest author Chris Spankovich reviewed some of the animal studies related to diet and hearing. As our conversation was ending, we had moved on to humans, and were talking about the Healthy Eating Index (HEI). This is a measure of diet quality that assesses conformance to federal dietary guidance. The HEI component and overall scores are from dietary recall interviews collected during the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). General findings from HEI studies indicate that only about 10% of us have a “good” diet. Our intake of “meats and beans” seems to be quite adequate, but—here’s a shocker—we seem to be lacking in categories like “dark green and orange vegetables.” And yes, men are somewhat worse than women in most all categories.

We of course hear a lot about how healthy eating can influence our weight, energy, bone strength, cholesterol, blood pressure and even brain performance, but not so much about hearing. There has been some interesting research on the topic, however.

Joining us again at 20Q is Christopher Spankovich, Ph.D., Research Assistant Professor at the University of Florida. His research in the past few years has focused on several different areas of diet, hearing loss and hearing protection. Our Question Man is back talking to Chris, so let’s join them.

Gus Mueller, Ph.D.

Contributing Editor

November 2012

To browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller articles, please visit www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Healthy Eating Makes for Healthy Hearing - Today’s Special

1. I really enjoyed our last little chat, but that was a while ago. Remind of the highpoints you thought I should remember.

1. I really enjoyed our last little chat, but that was a while ago. Remind of the highpoints you thought I should remember.

No problem. Recall that we went through a literature review of the relationship between diet and hearing loss, focusing on three primary areas: 1) caloric restriction, 2) macronutrients, and 3) micronutrients. The majority of the data evaluating the relationship between dietary nutrients and hearing loss come from animal models. However, there is some human epidemiological data suggesting a relationship between specific nutrients and hearing. As a whole, these data are largely consistent with the animal data.

2. You mentioned that there might be some limitations with the way human data is collected?

Correct. One of the common limitations is that most of these studies look at dietary intake using single nutrient analysis. In this kind of study, the subject keeps a food diary (a daily account of food intake and approximate amount), and the food diary is used to generate estimates of individual nutrient intake levels and total caloric intake.

3. For example? How specifically would this work?

If you report that you ate approximately 1 cup spinach, for example, we could estimate the amount of each nutrient you consumed (e.g. vitamin E, vitamin C, magnesium, and etc.) in that cup of spinach. In the single nutrient analysis, we would then add the total amount for each individual nutrient based on all of the foods reported in the food diary. We can then compare individual nutrient intake levels to our outcome of interest, which is hearing sensitivity. However, this approach has a number of limitations, as we discussed last time. So, what we have begun doing is looking at overall dietary quality, rather than looking at single nutrients. If you were to assume that vegetarians have healthier diets than others, you could for example compare hearing in vegetarians vs. non-vegetarians. Of course, not all vegetarians choose healthy foods, or achieve a balanced diet, which further highlights the importance of using an overall dietary quality index to quantify how healthy a person’s diet is.

4. Oh yes, it’s all coming back. You are referring to the Healthy Eating Index?

Exactly, good memory. The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) is a measure of how well a person’s diet conforms to the recommended dietary guidelines put forwards by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The HEI has a total possible score ranging from zero to 100, with 100 being the maximum (best) score, representing a diet that meets nutrient intake guidelines and has limited fats, sodium, cholesterol, etc. The total score is a sum of ten components, which are each worth 10 points. Components 1-5 measure the degree to which the person’s diet conforms to USDA serving recommendations for grains, vegetables, fruits, milk, and meat. Component 6 measures total fat as a percentage of total food energy intake, component 7 measures saturated fat as a percentage of total food energy intake, component 8 is a measure of total cholesterol intake, component 9 measures total sodium intake, and component 10 is a measure of the overall variety in a person’s diet. Components 1-5 are given the maximum score of 10 if the minimal recommended servings for each component are met or exceeded, while components 6-10 were given a maximum score of 10 if intake is less than a certain percentage of their total intake (USDA, 1995).

5. Right, and as I recall, you promised you would tell me about new data from some big nutrition survey?

I did promise you that, so let’s go to it. What you are referring to is the National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey (NHANES). The NHANES is a serial cross-sectional study performed in ongoing 2-year cycles. The NHANES includes interviews and physical examinations to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States. The survey examines a nationally representative sample of about 5000 persons each year. A subsample (approximately half) of the subjects undergo audiometric examination and interview including hearing thresholds, noise history, and tympanometry. The NHANES also includes a dietary interview and an extensive health interview including topics such as disease, physical activity, use of medications, drug use, smoking, etc. Findings from the survey are used to determine the prevalence of major disease conditions in the US population, and to determine risk factors for disease. Data from the survey are used in epidemiological studies and health science research, to help develop sound public health policy, direct and design health programs and services, and expand the health knowledge of the Nation (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm).

6. Thanks for clarifying. So what exactly is this relationship between hearing and the HEI?

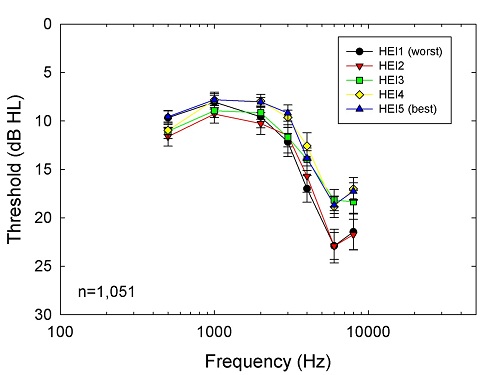

I’ll start with some research that I’ve been involved with. We performed an analysis evaluating the potential relationship between low frequency (0.5, 1 and 2 kHz) and high frequency (3, 4, 6, 8 kHz) pure-tone averages (LFPTA and HFPTA) and HEI as derived from the dietary interview conducted by the NHANES in the years 2001-2002. The sample included 1051 subjects after applying a variety of exclusion criteria, such as compromised middle ear function. Dietary quality was ranked, subjects were grouped by quintile (quintile 1: worst diets; quintile 5: best diets), and average auditory function was assessed as a function of HEI quintile (see Figure 1). HEI quintile 1 scores had a range of 28-53, and HEI quintile 5 scores had a range of 76-95.

Figure 1. HEI and Hearing Sensitivity. Subjects were categorized into HEI quintiles (1 = worst and 5 = best) and frequency-specific thresholds at frequencies ranging from 500 to 8000 Hz were compared. The results indicate comparable thresholds across HEI quintiles at the lower frequencies, but, at higher frequencies, thresholds were increased (i.e., poorer) in the two groups with the lowest (worst) HEI scores.

7. There does seem to be some difference in auditory function with improving HEI.

You’re right, the figure demonstrates an obvious separation in high frequency thresholds in HEI quintile 3-5 compared to the two lowest quintiles. Consistent with this, LFPTA did not show a reliable relationship with HEI, whereas HFPTA was significantly related to HEI score. Age, sex, noise exposure, race/ethnicity, and level of education were adjusted for in the analysis. I presented those data at the American Auditory Society meeting in 2012, and we are currently extending the sample size by including participants from additional years of the NHANES.

8. So these data from the NHANES, are they just sitting there waiting for someone to use them, or are you “special?”

Well, I’d like to think I’m special but the truth is this data is publically available. However, it is a lot of work to access, code, and analyze the data, so it helps to have a strong background in statistics, epidemiological methods, and familiarity with statistical packages like SAS, STATA, and SPSS. You don’t just download the data and throw things into a statistical package and see what is significant. There is a great deal of pre-planning, literature review, and preliminary analysis (lots of descriptive analysis and scatter plots) in regards to variables to include, variables to adjust, and chosen statistical methods. You go into these studies with a pre-planned analysis founded in methods derived from the literature with a research question and hypothesis in mind to be tested.

9. Okay, thanks. Getting back to the HEI—Does this index consider multivitamins? I thought I read somewhere about vitamin supplements being used to protect hearing?

The HEI does not account for nutrients derived from supplements, only those from food sources. However, there are current lines of study looking at supplements as otoprotectants. One such researcher is Colleen Le Prell, whom I mentioned the last time we talked. She’s an Associate Professor at the University of Florida. She and her colleagues at other institutions have identified benefits for a micronutrient supplement of vitamin A (delivered as beta-carotene), vitamin C, vitamin E, and magnesium (ACEMg).

The HEI does not account for nutrients derived from supplements, only those from food sources. However, there are current lines of study looking at supplements as otoprotectants. One such researcher is Colleen Le Prell, whom I mentioned the last time we talked. She’s an Associate Professor at the University of Florida. She and her colleagues at other institutions have identified benefits for a micronutrient supplement of vitamin A (delivered as beta-carotene), vitamin C, vitamin E, and magnesium (ACEMg).

10. Sounds interesting, I’m a vitamin taker myself. Can you tell me a little about what her team is finding?

I can do better than that! She’s agreed to answer your questions directly.

Thanks for including me, Chris. Let me start by saying our group was not the first to look at any of these nutrients. Every single one of these nutrients had been shown to confer protection against hearing loss, in animal models, when the nutrients were delivered for days, weeks, or even months prior to insult to the inner ear (using noise, or ototoxic drugs, as an insult). But, we all know that we can’t always plan for noise or an ototoxic drug that has some lifesaving benefit. What we really need are therapeutics that can be started at or near the time of the insult. The notion of combining agents to optimize benefits had just received pretty compelling support from a study in guinea pigs. In that study, a combination of salicylate and vitamin E was very effective in reducing permanent noise-induced hearing loss even when treatments started after the noise insult (Yamashita et al. 2005). Because salicylate can cause gastric issues for some people, and too much salicylate causes tinnitus, we were interested in whether other combinations might also be effective. My colleague Joe Miller, at the University of Michigan, and I therefore looked at another antioxidant combination, entirely composed of ingredients that are already available “over the counter” as dietary supplements. We picked beta-carotene, vitamins C and E, and magnesium (Mg) because they get into different parts of cells, and they scavenge different radicals. There was also a lot of safety data for the vitamins, which had been shown to reduce the progression of macular degeneration in a 7-year human trial (AREDS, 2001). Finally, Mg had been shown to reduce NIHL in humans in other earlier studies (Attias et al., 1994, 2004).

11. I’m familiar with those vitamins. So what did you find?

To our surprise, combining the vitamins with Mg resulted in robust protection of the ear, with treatments starting just 1 hour before the noise insult, even though neither the vitamins, nor the Mg, provided protection when used alone at these short pre-noise treatment times (Le Prell et al., 2007). Work with vitamins, other antioxidant agents, and some novel alternatives to antioxidants, was recently reviewed in detail in Le Prell and Bao (2011).

12. But does this finding transfer to humans?

Good question—you’re probably referring to the comment Chris made earlier in this discussion about the difference between demonstrating something in an animal model, and showing the effect translates to humans. I couldn’t agree with him more. So, we are ramping up to begin a clinical trial that will test these agents in human subjects. The active agents may be vitamins and minerals, but, since we are looking at the potential for protection of human hearing, these studies did need to go through an Investigational New Drug (IND) review process through the US FDA.

13. So, let’s say the findings are positive. Does source matter? Do I have to eat a healthy diet, or can I just take a multivitamin supplement?

Well, it seems unlikely that any supplement could “replace” a healthy diet given the variety of different vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients that need to come from our diet. And, remember, there are data that suggest too much fat in your diet is harmful. Dietary supplements aren’t going to cut your fat for you. So, my answer would have to be no, you can’t “just” take a multivitamin supplement and get all of the benefits that might come from a healthy diet.

14. Sorry to ignore you Chris, do you agree with Colleen?

I agree. The nutrients derived from food sources represent the full spectrum of nutrients and phytochemicals associated with that specific food (including the numerous chemical forms) and there are implications for how food is digested and metabolized compared to a capsule.

In contrast to foods, most over-the-counter multivitamins contain isolated synthetic versions of nutrients, commonly limited to a single chemical form. For example, vitamin E has 8 iso-forms, but most vitamins include only 1 of these; i.e., alpha-tocopherol.

15. Is there some sort of “standard” concerning what goes into these vitamins?

(Colleen). Yes and no. Over-the-counter dietary supplement products are not regulated by the FDA under the same standards as drug products. Dietary supplements are regulated per the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHAE). Under DSHEA, the manufacturer is responsible for ensuring that the product is “safe” and that current Good Manufacturing Processes (cGMP) are followed (so that contaminants are not introduced during manufacturing). Manufacturers don’t need to prove a supplement is effective. That’s why so many dietary supplements have a disclaimer. You know the one:

“These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration.This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

Personally, I am very excited to see several agents that are going through a more complete evaluation in the form of clinical trials evaluating the prevention of noise-induced hearing loss, under oversight of the FDA.

(Chris) Some key questions still remain: (1) Can a healthy diet prevent susceptibility to hearing loss?, (2) Does someone with a poor diet have increased risk of hearing loss?, (3) Does someone with a poor or deficient diet gain protection from a supplement? And, (4) Does someone with a healthy diet have added protection from a supplement? These are all areas that need to be explored in future research.

16. You both have been talking about clinical trials for noise-induced hearing loss. Does the cause of the hearing loss matter?

(Colleen) There is a lot more work to be done in this area. Our colleague Kathy Campbell, at Southern Illinois University, has done a lot of work with D-methionine for prevention of drug-induced hearing loss. In Campbell and Le Prell (2011), we reviewed the use of antioxidants for prevention of hearing loss after different ototoxic drugs. Clearly, there is a lot of promise for this class of agents. For nutrient supplements, the work is just beginning. Joe Miller and I simultaneously initiated studies on prevention of aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss in our labs at UF and at the University of Michigan. We presented the first results at the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (ARO) 2012 mid-winter meeting. Data are also just now beginning to come in as part of an ongoing study on age-related hearing loss using a mouse model here at UF. Really, as far as human diet goes, this is a question we don’t have an answer for at this time.

That’s it for me—I’ll turn things back over to Chris.

17. Thanks Colleen. Chris, do you have anything to add to my last question?

I certainly agree with Colleen’s comments. Further studies will be needed where we can manipulate diet and look at susceptibility to noise, age, and ototoxic drugs. It is my opinion that the greatest impact of a healthy diet will likely be in reducing age-related hearing loss and that a healthy diet and addition of supplements will be best for more acute application such as for noise exposure and ototoxic drugs. We have some data that we are working on that suggest that diet may have its’ greatest impact in older age groups, but early adoption of healthy eating practices is recommended. In my opinion, hearing loss is not an inevitable outcome. Age-related hearing loss is an inaccurate term; really it is a multifactoral-related hearing loss. Ototoxic drugs, noise history, health history, diet and genetics are all going to be contributing factors to what we call age-related hearing loss. We may not be able to change someone’s genetics (at least for now), but we may be able to prescribe a diet and supplement based therapy based on that individuals biochemistry, called nutritional genomics or nutrigenetics.

18. So I’ve been thinking about all this—Do you think audiologists should be making dietary recommendations?

Well, most audiologists are not nutritionists. However, that does not mean we can’t advise our patients to eat healthy diets and exercise. They are hopefully hearing this information from their other health care providers as well. In reality, most physicians have received very little course work in nutrition, usually a few lectures or if lucky, one course. However, you should advise your patients to discuss any dietary supplements and changes in physical activity with their primary care provider.

19. What are the most important take home messages from all this research that you have discussed?

- Understanding the factors that influence susceptibility to hearing loss are critical to design and application of interventions.

- We are acquiring evidence that nutrients and dietary health can influence susceptibility to hearing loss and may lead to development of dietary guidelines and/or supplement based treatments to help diminish susceptibility to hearing loss.

- Specific recommendations may be dependent on insult leading to hearing loss, whether it is age, noise, or drugs or the individual’s biochemistry (nutritional genomics).

- Supplements are not a substitute for a healthy diet, but they may well prove to provide specific benefit for protection from hearing loss.

20. A lot of information. Where do I start?

A place we can start now is by recommending healthy lifestyles to our patients. We all have patients on a statin (to lower cholesterol), or high blood pressure medications; patients who are overweight, and/or have type II diabetes. A healthy diet and exercise can help alleviate those issues. We hope that a healthy diet will ultimately be shown to also reduce susceptibility to further hearing loss, tinnitus, and/or dizziness. We can’t make those promises, but, advice to make healthy eating decisions surely can’t hurt.

Disclosure: Colleen Le Prell is a co-inventor on US 7,951,845 (Miller et al., 2011) and US 7,786,100 (Miller et al., 2010). These patents, owned by the University of Michigan, describe specific combinations of agents proposed to reduce noise induced hearing loss. Dr. Le Prell is supervising clinical trials with two different proposed therapeutic agents (NCT00808470, NCT01444846).

References

Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. 2001. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch. Ophthalmol. 119, 1417-36.

Ahn, J.H., Kang, H.H., Kim, Y.J., Chung, J.W. 2005. Anti-apoptotic role of retinoic acid in the inner ear of noise-exposed mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335, 485-90.

Attias J., Sapir S., Bresloff I., Reshef-Haran I. & Ising H. 2004. Reduction in noise-induced temporary threshold shift in humans following oral magnesium intake. Clin. Otolaryngol., 29, 635-641.

Attias, J., Weisz, G., Almog, S., Shahar, A., Wiener, M., Joachims, Z., Netzer, A., Ising, H., Rebentisch, E., Guenther, T. 1994. Oral magnesium intake reduces permanent hearing loss induced by noise exposure. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 15, 26-32.

Biesalski, H.K., Wellner, U., Weiser, H. 1990. Vitamin A deficiency increases noise susceptibility in guinea pigs. J. Nutr. 120, 726-37.

Campbell, K.C., Le Prell, C.G. 2011. Potential therapeutic agents. Semin. Hearing in press.

Colman, R.J., Anderson, R.M., Johnson, S.C., Kastman, E.K., Kosmatka, K.J., Beasley, T.M. et al. (2009). Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science 325 (5937), 201-204.

Durga, J., Verhoef, P., Anteunis, L.J., Schouten, E., Kok, F.J. 2007. Effects of folic acid supplementation on hearing in older adults: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 146, 1-9.

Evans, M.B., Tonini, R., Shope, C.D., Oghalai, J.S., Jerger, J.F., Insull, W., Jr., Brownell, W.E. 2006. Dyslipidemia and auditory function. Otol. Neurotol. 27, 609-14.

Fowler, C.G., Torre, P., Kemnitz, J.W. (2002). Effects of caloric restriction and aging on the auditory function of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta): The University of Wisconsin Study. Her Res, 169 (1-2), 24-35.

Gopinath, B., Flood, V.M., McMahon, C.M., Burlutsky, G., Brand-Miller, J., Mitchell, P. 2010b. Dietary glycemic load is a predictor of age-related hearing loss in older adults. J. Nutr. 140, 2207-12.

Gopinath, B., Flood, V.M., McMahon, C.M., Burlutsky, G., Spankovich, C., Hood, L.J., Mitchell, P. 2011a. Dietary antioxidant intake is associated with the prevalence but not incidence of age-related hearing loss. J. Nutr. Health Aging 15, 896-900.

Gopinath, B., Flood, V.M., Teber, E., McMahon, C.M., Mitchell, P. 2011b. Dietary intake of cholesterol is positively associated and use of cholesterol-lowering medication is negatively associated with prevalent age-related hearing loss. J. Nutr. 141 (7), 1355-1361.

Haupt, H., Scheibe, F. 2002. Preventive magnesium supplement protects the inner ear against noise-induced impairment of blood flow and oxygenation in the guinea pig. Magnesium Research 15, 17-25.

Heman-Ackah S.E., Juhn S.K., Huang T.C. & Wiedmann T.S. 2010. A combination antioxidant therapy prevents age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6 mice. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 143, 429-434.

Hou, F., Wang, S., Zhai, S., Hu, Y., Yang, W., He, L. 2003. Effects of alpha-tocopherol on noise-induced hearing loss in guinea pigs. Hear. Res. 179, 1-8.

Ikeda, K., Kusakari, J., Kobayashi, T., Saito, Y. 1987. The effect of vitamin D deficiency on the cochlear potentials and the perilymphatic ionized calcium concentration of rats. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 435, 64-72.

Kalkanis, J.G., Whitworth, C., Rybak, L.P. 2004. Vitamin E reduces cisplatin ototoxicity. Laryngoscope 114, 538-42.

Kashio, A., Amano, A., Kondo, Y., Sakamoto, T., Iwamura, H., Suzuki, M., Ishigami, A., Yamasoba, T. 2009. Effect of vitamin C depletion on age-related hearing loss in SMP30/GNL knockout mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 390, 394-8.

Lautermann, J., McLaren, J., Schacht, J. 1995a. Glutathione protection against gentamicin ototoxicity depends on nutritional status. Hear. Res. 86, 15-24.

Le Prell, C.G., Bao, J. 2011. Prevention of noise-induced hearing loss: potential therapeutic agents. In: Le Prell, C.G., Henderson, D., Fay, R.R., Popper, A.N., (Eds.), Noise-Induced Hearing Loss: Scientific Advances, Springer Handbook of Auditory Research. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, New York.

Le Prell, C.G., Hughes, L.F., Miller, J.M. 2007. Free radical scavengers vitamins A, C, and E plus magnesium reduce noise trauma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 42, 1454-1463.

Lopez-Torres, M., Barja, G. 2008. Lowered methionine ingestion as responsible for the decrease in rodent mitochondrial oxidative stress in protein and dietary restriction possible implications for humans. Biochim Biophys Acta 1780, 1337-47.

Mattison, J.A., Roth, G.S., Beasley, T.M. et al. (2012). Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkey from the NIA study. Nature 489, 318-322.

McFadden, S.L., Woo, J.M., Michalak, N., Ding, D. 2005. Dietary vitamin C supplementation reduces noise-induced hearing loss in guinea pigs. Hear. Res. 202, 200-8.

Miller, J.M., Le Prell, C.G., and Yamashita, D. US 7,786,100 B2, Composition and method of treating hearing loss. Awarded August 31, 2010.

Miller, J.M., Le Prell, C.G., Schacht, J., and Prieskorn, D.M. US 7,951,845, Composition and method of treating hearing loss. Awarded May 31, 2011.

Ohinata, Y., Yamasoba, T., Schacht, J., Miller, J.M. 2000. Glutathione limits noise-induced hearing loss. Hear. Res. 146, 28-34.

Pillsbury, H.C. 1986. Hypertension, hyperlipoproteinemia, chronic noise exposure: is there synergism in cochlear pathology? Laryngoscope 96, 1112-38.

Quaranta, A., Scaringi, A., Bartoli, R., Margarito, M.A., Quaranta, N. 2004. The effects of 'supra-physiological' vitamin B12 administration on temporary threshold shift. Int. J. Audiol. 43, 162-5.

Rosen, S., Olin, P., Rosen, H.V. 1970. Diery prevention of hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol 70, 242-7.

Seidman, M.D. 2000. Effects of dietary restriction and antioxidants on presbyacusis. Laryngoscope 110, 727-38.

Shargorodsky, J., Curhan, S.G., Eavey, R., Curhan, G.C. 2010. A prospective study of vitamin intake and the risk of hearing loss in men. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 142, 231-6.

Shim, H.J., Kang, H.H., Ahn, J.H., Chung, J.W. 2009. Retinoic acid applied after noise exposure can recover the noise-induced hearing loss in mice. Acta Otolaryngology 129, 233-8.

Someya, S., Tanokura, M., Weindruch, R., Prolla, T.A., Yamasoba, T. 2010. Effects of caloric restriction on age-related hearing loss in rodents and rhesus monkeys. Curr Aging Sci 3, 20-5.

Someya, S., Yamasoba, T., Weindruch, R., Prolla, T.A., Tanokura, M. 2007. Caloric restriction suppresses apoptotic cell death in the mammalian cochlea and leads to prevention of presbycusis. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 1613-22.

Spankovich, C., Hood, L., Silver, H., Lambert, W., Flood, V., Mitchell, P. 2011. Associations between diet and both high and low pure tone averages and transient evoked otoacoustic emissions in an older adult population-based study. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 22, 49-58.

Torre, P., Mattison, J.A., Fowler, C.G., Lane, M.A., Roth, G.S., Ingram, D.K. (2004). Assessment of auditory function in rhesus monkeys (macaca mulatta): effects of age and calorie restriction. Neurobiol Aging 25 (7), 945-954.

United States Department of Agriculture 1995. Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion: The Healthy Eating Index.

Yamashita, D., Jiang, H.-Y., Le Prell, C.G., Schacht, J., Miller, J.M. 2005. Post-exposure treatment attenuates noise-induced hearing loss. Neuroscience 134, 633-642.