From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

Like most medically-related professions, as audiologists we have a lot of different pathologies and disorders that we need to be familiar with. There are those like middle ear effusion, presbycusis and noise-induced hearing loss that we see most every day if we work in a typical clinic. There are others, however, that we might only see once a month, once a year, or maybe...once a career! Or, it could be that we’re seeing them more often than we think, but just don’t know it.

We’re fortunate this month at 20Q, to have as our guest author, Dr. Linda Hood, who has been part of the identification, understanding and treatment of one of these lesser-known pathologies, auditory neuropathy/auditory synaptopathy (AN/AS), since the time it was first reported in the literature in the mid-1990s. But more on Linda in just a moment.

The “appropriate” terminology for this disorder has changed slightly over the years, partly because of the various mechanisms underlying the different forms. Starting out as simply auditory neuropathy, broader terms have been applied, such as “auditory synaptopathy,” “auditory dys-synchrony” and “auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD)”; all leading to AN/AS. More important, however, than the precise terminology, are all the new discoveries in this area—which is why it’s nice to have a leading expert handy.

Linda J. Hood, Ph.D., is a Professor and Hearing Scientist in the Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences and Director of the Auditory Physiology Laboratory at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN. Citing her accomplishments over the past several decades would fill several pages, but here is a quick glimpse.

Her publications and research productivity are well known and respected internationally. She has received numerous grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, and serves on working groups of the NIH-NIDCD. She also is a consultant and active participant in the work of the World Health Organization.

Among other awards, Dr. Hood has received the Honors of the Association from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, the Jerger Career Award for Research in Audiology from the American Academy of Audiology, the Hallowell Davis Lectureship from the International Evoked Response Audiometry Study Group, the Aram Glorig Award from the International Society of Audiology, and most recently, the Life Achievement Award from the American Auditory Society.

I’m willing to place a sizeable bet that Dr. Hood also is the only individual to accomplish the hat-trick of being elected president of the American Auditory Society, the International Society of Audiology and the American Academy of Audiology. Regarding the latter, it was back in 1992, that she was elected the 4th president of the Academy, handily beating out the opposing dark-horse candidate named Mueller.

Whether you see AN/AS patients regularly, every now and then, or hardly ever, you’ll find a lot of useful information in Linda’s review of what is new and emerging in this intriguing area.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Auditory Neuropathy and Auditory Synaptopathy - Genotyping and Phenotyping

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Discuss methods used to identify AN/AS.

- Discuss new developments in the identification of AN/AS.

- Discuss management options for patients with AN/AS.

1. It’s my understanding that the condition of auditory neuropathy is relatively new to the profession of audiology?

Relatively so, yes. We are nearing 30 years since the first modern descriptions of patients with auditory neuropathy (AN; Starr et al., 1996) or auditory nerve disorder (Kaga et al., 1996) were published in 1996. Over the ensuing years, we have integrated identification and management of AN into standard screening and diagnostic protocols. We have learned that this condition can occur in isolation, affecting only the auditory system, as well as in conjunction with other, non-auditory neural disorders. This condition represents abnormal function emanating from several sources in the cochlear-peripheral neural pathway. Infants at risk for AN can be identified at birth though further testing over time is generally needed to distinguish AN from neuromaturation. Specific genetic variants are associated with some forms of AN and cochlear implants are an effective management option.

Areas of discovery that are significantly enhancing our understanding of this auditory disorder involve the identification of gene variants associated with AN and in-depth characterization of patients’ auditory responses. Importantly, this information is providing the ability to more accurately distinguish and describe some forms of AN. There are a lot of new things to talk about!

2. Great, because I have a lot of questions. But let’s make sure I have the basics correct—how exactly is the presence of AN determined?

As audiologists, we’ve all been trained to conduct a battery of tests, and at the conclusion, make a reasonable statement regarding a probable diagnosis. This often is based on the patient history, degree, and configuration of the hearing loss. Things are a little more complicated with AN. Behavioral test results vary widely across patients; however, two behavioral measures may provide some clues, though there still is variation across patients. First, speech recognition in noise, or in other competing stimulus conditions, is poorer than expected, and, second, temporal processing such as gap detection is typically poor. Behavioral pure-tone thresholds and speech recognition in quiet vary widely and thus are not useful in differential diagnosis. Comprehensive descriptions of test results across large numbers of patients can be found in articles by Berlin et al. (2010) and Morlet et al. (2023).

Given the limitations of the traditional behavioral test battery, AN is identified clinically by comparing responses to measures of cochlear and neural auditory function. Appropriate cochlear measures are those sensitive to cochlear active processes/outer hair cell (OHC) function, specifically otoacoustic emissions (OAE) and cochlear microphonics (CM), which typically are present in these patients. Cochlear responses are compared to tests of peripheral neural function, specifically the auditory brainstem response (ABR) and middle-ear muscle reflexes (MEMR). The combination of present cochlear active/IHC processes and absent or highly abnormal peripheral neural responses identifies patients with or, in the case of newborn infants, at risk for AN/AS.

Utilizing auditory brainstem responses in newborn hearing screening allows accurate identification of newborns who are at risk for AN/AS and this is the recommended approach when screening newborns in the NICU, as AN/AS occurs more often (but not always!) in this population (JCIH, 2007; Berg et al., 2005). Comparing ABRs recorded using condensation and rarefaction stimuli (typically, clicks) serves to characterize the cochlear microphonic (CM) and to differentiate cochlear from neural components of the ABR (Berlin et al., 1998). Through the years, these methods of evaluating patients with AN/AS continue as the clinical standards of practice.

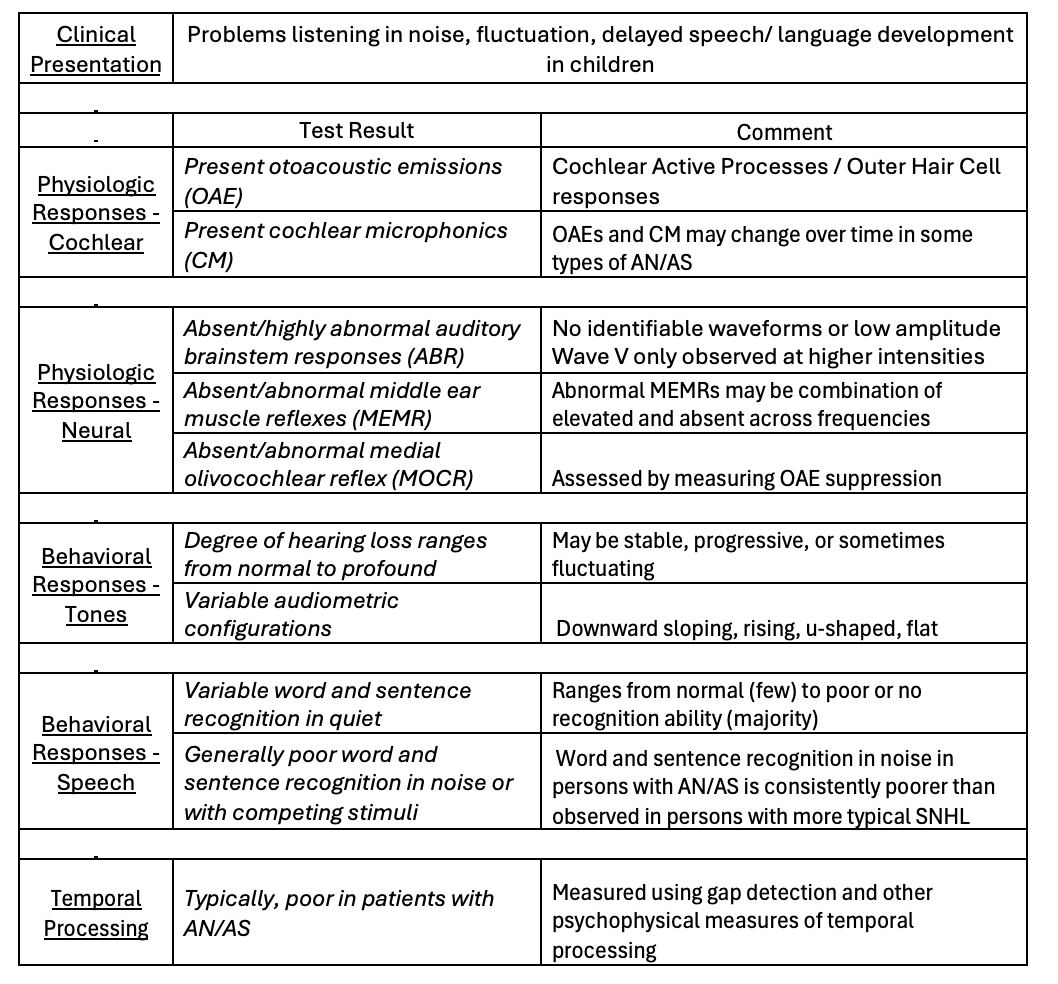

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and test results seen in patients with AN/AS.

Table 1. A summary of characteristics and test results seen in patients with AN/AS.

3. You mentioned earlier that areas of discovery that are significantly enhancing our understanding of this auditory disorder involve the identification of associated genes?

Most definitely—let me review a few terms to get us started—some may be familiar, others possibly not. The term “genotype” broadly refers to the genetic makeup of an organism, for purposes of our discussion, humans. The genotype describes a person’s complete set of genetic material. Genotyping is the process of analyzing the genetic sequences to determine differences in the genetic make-up (genotype) of an individual by examining their individual’s DNA sequences. These methods are used to identify genetic variants by comparison to other individual’s genetic sequences or a reference sequence.

The term “phenotype” refers to observable and testable characteristics of an individual. This can include hearing sensitivity, heart rate, height, eye color, etc. When we complete an audiological evaluation, we obtain information about various aspects of an individual’s hearing phenotype.

Comparing genotype and phenotype allows us to understand the physical characteristics of individuals and how they may relate to their genetic makeup. In recent years there have been several developments in genetics and methods to accurately phenotype auditory neuropathy (AN) and auditory synaptopathy (AS).

4. You have been using the term “auditory neuropathy, but now you’ve added “auditory synaptopathy.” The same thing?

No, not in the context of what researchers are learning about the various mechanisms underlying different forms of AN/AS and the emerging knowledge. The majority of the first group of patients described in the literature (Kaga et al., 1996; Starr et al., 1996) displayed neural symptoms affecting non-auditory as well as auditory systems, leading to the term ‘auditory neuropathy,’ a term that was coined by Dr. Arnold Starr. In this case the term ‘auditory neuropathy’ is accurate since, in the group of patients described, it was most likely that the auditory nerve (eighth cranial nerve) was involved as the site of abnormal function.

Over the following years, the term ‘auditory neuropathy’ has been broadly associated with functional abnormalities affecting the inner hair cells (IHC), the synaptic transmission between the IHCs and auditory nerve, and disrupted function of the auditory nerve itself, despite the possibility that the auditory nerve is not the primary site of abnormality in many of the patients. To encompass the wide variation in characteristics observed across patients and multiple sites of abnormality, broader terms have been applied, including “auditory synaptopathy,” “auditory dys-synchrony” and “auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder”, often abbreviated ANSD.

Genetic discoveries and recent research related to sensory, synaptic, and neural mechanisms provide insight into the function, or dysfunction along this pathway and provide a basis to more accurately distinguish pre- and post-synaptic forms of this condition. With these insights, it is possible to distinguish a pre-synaptic form of AN, more accurately called auditory synaptopathy (AS) from post-synaptic forms which involve function of the auditory nerve and can accurately be termed auditory neuropathy (AN). Thus, we can distinguish between disrupted auditory nerve activity (“auditory neuropathy”) and disordered IHC synaptic function (“auditory synaptopathy”). Moser and Starr (2016) provide an excellent review of insights into the mechanisms involved and describe how AS differs from AN.

Incorporating genetic analysis and physiologic measures of cochlear and neural function into clinical evaluation of patients of all ages provide clinicians with the ability to separate patients with AN and/or AS from those with typical forms of sensorineural hearing loss.

5. Interesting. What is involved in auditory synaptopathy?

Auditory synaptopathy focuses on the synaptic juncture of the inner hair cells and the eighth cranial (cochlear branch of the auditory) nerve. A highly specialized type of synapse found at the IHC-nerve juncture is called a ‘ribbon’ synapse. Genetic and physiologic studies in animal and human subjects have demonstrated the key role of IHC ribbon synapses between the inner ear and spiral ganglion neurons in the transduction process that mediates neurotransmitter release. Disruption or compromised function of the IHC ribbon synapses affects processes needed for neurotransmitter loading and release, necessary for activation of neural responses. These synapses encode sound with sub-millisecond, high temporal precision. This characteristic is consistent with the breakdown in temporal processing ability that has been documented using psychophysical measures of temporal processing, such as temporal gap detection, in patients with AN/AS.

6. Is it fairly easy to differentiate AN from AS?

Guess that depends on your definition of “easy.” Identification of genes involved in synaptic versus neural processes through molecular genetic testing, along with advanced physiologic and psychophysical testing can distinguish AS from AN. As I mentioned earlier, AS involves the synapse between the IHCs and spiral ganglion neurons while AN is associated with abnormal neural activity due to various aspects dysfunction within the neural components of the pathway. AN can be associated with a number of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies, such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Friedreich’s Ataxia, and other syndromic forms of AN, where motor as well as sensory function is affected. There also are non-syndromic forms of AN. Relative to your question, we can talk more later about sensitive physiological approaches used in evaluating AS and AN.

7. What are some of the things we’ve learned about AN/AS from genetics research?

Families with multiple family members with AN/AS strongly suggest underlying genetic factors. Families with two or more affected siblings and parents with normal auditory function are consistent with a recessive inheritance pattern. The majority of cases of non-syndromic AN/AS are autosomal recessive consistent with findings in other forms of hereditary hearing loss. Multiple generations within families also can display AN/AS, consistent with a dominant inheritance pattern. Patients with syndromic AN/AS may be first diagnosed with peripheral neuropathy followed by auditory complaints several years later, though this is not always the case. Since AN/AS clearly has hereditary aspects, it is important to consider family history and consider risk of AN/AS for subsequent siblings in families who already have one or more members with AN/AS.

Gene variants have been identified in associated with non-syndromic AN/AS, as well as situations where AN/AS is part of a syndrome, often associated with other types of neural disorders. Some examples include autosomal dominant auditory neuropathy (AUNA1), autosomal recessive auditory neuropathy (AUNB1), genetic variants associated with demyelinating disease, hereditary sensorimotor neuropathies, Charcot Marie Tooth disease, Friedreich ataxia, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, autosomal dominant optic atrophy, and mitochondrial abnormalities.

8. Are there certain genes that are of specific interest?

Considerable research links the OTOF gene to non-syndromic recessive auditory synaptopathy, as well a form of sensorineural hearing loss termed DFNB9. The OTOF gene encodes the production of otoferlin, a transmembrane protein belonging to the ferlin protein family involved in calcium binding. Studies in mice indicate that otoferlin plays a crucial role in vesicle release at the synapse between IHCs and auditory nerve fibers. Patients who display the AS phenotype must have two variant alleles (copies), consistent with the recessive inheritance pattern. Otoferlin is expressed in the sensory IHCs and is associated with synaptic function. The protein related to OTOF codes for the development and maintenance of the inner hair cell synapse; thus, variants in the OTOF gene are associated with a form of AN/AS designated as auditory synaptopathy. Some patients with OTOF variants display a temperature sensitive form of AN/AS (e.g., Varga et al., 2006; Marlin et al., 2010) which will be discussed here later. It is important to note that OTOF variants also are associated with an autosomal recessive sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) which is designated as DFNB9 and is typically associated with severe to profound prelingual hearing loss.

9. I hope I’ll be able to remember all this! And there is probably more.

There is, and it only gets better! Patients with OTOF variants associated with auditory synaptopathy show the characteristics and physiologic test findings expected in patients with AN/AS. Cochlear responses are characterized by present CM at normal amplitudes, present summating potential (SP), and present OAEs, though OAEs may change over time.(Rodriguez-Ballesteros et al., 2008; Santarelli et al., 2015a). In patients with OTOF gene variants, neural responses, including middle-ear muscle reflexes (MEMR) and the ABR, are either absent (most often) or highly abnormal. The abnormal neural responses are attributed to compromised neurotransmitter release, which results in absent or highly abnormal ABRs, consistent with a functional loss of auditory nerve input. Recordings obtained using transtympanic electrocochleography (ECochG) indicate an abnormal, prolonged negative, response in the compound action potential (CAP) (Santarelli et al., 2015a). As observed in other types of AN/AS, behavioral test results are variable. Pure-tone thresholds in AN/AS patients with OTOF variants are most often associated with severe hearing loss with poor word recognition, though this is not always the case.

A recent report provided an analysis of genotype-phenotype characteristics in individuals with AN/AS and OTOF gene variants (Thorpe et al., 2022). These researchers compared audiometric thresholds, OAEs, and specific variant types in a cohort of 49 patients. Results indicate that specific genetic variant types are associated with poorer audiometric thresholds, reduced or absent OAEs. As has been seen in analysis of variant types in patients with hearing loss related to GJB2 (connexin 26), the ability to analyze large cohorts of patients provides valuable information about genotype-phenotype relationships that can inform clinical practice (e.g., Snoeckx et al., 2005).

10. But some patients can have only a mild hearing loss, right?

Correct. While congenital, profound hearing loss is the most common phenotype found in patients with variants in the OTOF gene, this is not always the case. Some patients with biallelic OTOF variants (both alleles of a single gene, paternal and maternal), demonstrate a less common phenotype of milder hearing loss associated with AN/AS (e.g., Marlin et al., 2010; Santarelli et al.2021; Varga et al., 2006). Some are progressive in nature while others, including a patient whom we have followed for more than 20 years, show stable auditory characteristics. OAEs are present and ABRs are absent or highly abnormal, consistent with an AN/AS diagnosis. In these cases of a milder form, it is possible that differences from those with OTOF variants and profound hearing loss is related to modulation/influence of other genes and interactions among OTOF and other proteins that may provide partial compensation in function. Further investigation is needed with accumulation of more patients with sensitive genotype and phenotype data.

11. I think I saw somewhere that body temperature can impact AN/AS? True?

Yes, in some patients with AN/AS, communication problems are confounded by fluctuation in auditory function that is linked to changes in body temperature (elevation of as little as 1 degree Celsius). This temperature sensitive form of AN/AS is less common, but challenging to manage because of the fluctuations in auditory capacity. Some forms of temperature sensitive AN/AS have been linked to variants in the OTOF gene (e.g., Varga et al., 2006; Marlin et al., 2010).

A characteristic of temperature-sensitive AN/AS is wide variation in characteristics among patients and fluctuating hearing ability on a day-to-day and moment-to-moment basis. Hearing can fluctuate from normal or mild loss levels to the profound loss level without predictability. Based on the variation among patients in changes with temperature elevation, accommodations in management need to be individualized.

In a patient whom we have followed for many years, when body temperature is normal, pure-tone thresholds and word recognition are within the normal range. Biallelic OTOF variants have been documented in this patient. OAEs are present while ABR and MEMRs are absent both with normal and elevated body temperature, consistent with the diagnosis of AN/AS. With temperature elevation, pure-tone thresholds and word recognition decrease to varying degrees, and do not consistently change together. It is important in this patient to note that, even when behavioral hearing thresholds and speech recognition in quiet are good, the patient still displays neural dys-synchrony, characterized by lack of a synchronous ABR (absent ABR), and absent MEMRs, despite present OAEs. Difficulty is noted in speech perception in challenging conditions such as background noise, both without and with temperature elevation, though significantly greater difficulty occurs when body temperature is elevated.

These characteristics are consistent with other reports such as that documenting auditory function in three children followed by Starr et al. (1998). Hearing ability in these children moved into the profound hearing loss range with temperature elevation and then returned to usual patterns when temperature returned to normal. Some test results were normal regardless of body temperature (OAEs, CM, and tympanometry), others moved from mild involvement to markedly abnormal when temperature was elevated (ABRs and pure tone hearing thresholds). Both acoustic reflexes (middle-ear muscle reflex, MEMR, and medial olivocochlear reflex, MOCR) were consistently abnormal regardless of normal or elevated temperature. As with the patient described above, these characteristics are all consistent with the diagnosis of AN/AS. Genetic test information is not available for these patients, likely related to testing in an earlier time period (leading up to publication in 1998), prior to availability of extensive genotyping related to AN/AS.

12. Do these patients obtain benefit from hearing aids or cochlear implants?

The majority of patients with AN/AS have not successfully benefitted from the use of amplification. However, some patients have shown benefit and, therefore, trial with hearing aids is part of the recommended management process. It’s important to remember that individuals with AN/AS have the greatest amount of difficulty with discrimination of speech, separating the sounds into meaningful information. This is typically related to abnormal peripheral neural processing, either due to disordered input from the cochlea via the synaptic juncture and/or dysfunction within the cochlear nerve.

While amplification of sound may not be helpful, patients with AN/AS generally do benefit from FM systems. This makes sense since FM systems are designed to reduce the interference from background noise, which is a particular problem observed in AN/AS patients.

Patients with OTOF variants, however, have been shown to benefit from cochlear implantation, when their audiologic profile meets the criteria for CI related to AN/AS. Since OTOF is associated with a synaptic site of dysfunction, patients with this form of AN/AS typically are expected to have preserved neural function. This is confirmed by the presence of electrically evoked compound action potentials post-implantation. Based on reported findings, patients with AN/AS due to OTOF variants who meet criteria for CI are typically expected to have successful outcomes with CI.

An example of this outcome describes a cohort of six children, aged 4 months to 2 years, with OTOF variants and thresholds in the profound hearing loss range who were implanted and demonstrated excellent improvement within 3 months of CI use (Santarelli et al., 2015a). Prior to CI they all had hearing sensitivity in the profound hearing loss range, present OAEs, absent ABRs, and poor speech perception. Amplification was tried in all children prior to implantation, without success. Post-CI performance indicated speech perception scores ranging from 90-100%. Furthermore, post-CI electrical compound action potentials (eCAP) had normal morphology, consistent with preserved nerve fibers.

In a different cohort of patients, who had a milder version of AS related to OTOF variants, Santarelli et al. (2021) documented that cochlear implantation also provided a valuable management strategy for this group. These patients, despite pure-tone threshold sensitivity in the mild or moderate range, demonstrated very poor speech recognition pre-implant, even in quiet. Speech recognition scores improved significantly in all patients with use of a CI.

13. What other type of treatment is considered?

An exciting new area of discovery related to auditory synaptopathy and OTOF gene varients is in the area of gene therapy. In a special session at the 2024 Midwinter Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (ARO, 2024), information about recent gene therapy trials involving OTOF was presented. These clinical trials, underway by several groups, focus on replacing defective OTOF genetic material at the level of the cochlea with a functional gene that produces otoferlin. In the gene therapy trial, a small volume of liquid (carried by a specific vector) containing the normal otoferlin gene is injected into the cochlea. Trials are either underway or about to begin at several sites around the world. In the limited number of patients enrolled to date, findings indicate at least partial hearing improvement. These early findings hold great promise for patients with OTOF variants that affect auditory function.

14. Are there other genes of special interest?

Neural representation of signals can be affected by loss of neurons, demyelinating disease, and is associated with hereditary motor sensory neuropathies, as well as non-syndromic and syndromic hearing loss, and variable inheritance patterns. One form of syndromic AN is associated with optic nerve atrophy that follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Dominant Optic Atrophy (DOA) is one of the most common genetically based optic atrophies characterized by progressive bilateral loss of vision that begins in childhood. The vision loss is associated with degeneration of retinal ganglion cells. Many, though not all, cases of DOA are associated with variants in the OPA1 (optic atrophy 1) gene and the gene variants can result in significantly reduced production of the associated protein. Patients may present as non-syndromic (vision loss only) or syndromic that can involve hearing loss, ataxia, and other characteristics, along with the primary vision loss. Hearing loss characteristics related to the OPA1 gene variant suggest a neural basis with altered function of terminal unmyelinated portions of auditory nerve.

15. Do these patients commonly have abnormal audiologic findings?

Hearing loss is the second most prevalent feature after optic atrophy in patients with OPA1 gene variants, and hearing loss typically follows onset of visual impairment with slow progression. Whether hearing is affected depends on the specific type of genetic variant present in a patient.

Santarelli et al. (2015b) studied two groups of patients with OPA1 variants and reported high occurrence of auditory dysfunction in patients harboring missense variants of the OPA1 gene. Ten patients aged 5-58 years reported onset of vision problems in childhood or adolescence that preceded the onset of hearing loss in seven patients. The other patients had either congenital hearing loss or noted speech perception difficulty prior to vision symptom onset.

Hearing sensitivity, measured by behavioral pure-tone thresholds, ranged from mild to profound hearing loss categories. Speech recognition was below normal ranges. The pattern of hearing test findings is consistent with AN characteristics, with patients demonstrating preserved OAEs and absent or abnormal ABRs and MEMRs. Detailed assessment using transtympanic ECochG indicated normal function of inner and outer hear cells; normal summating potential (SP) latency and amplitude was consistent with IHC preservation. Neural responses show prolonged negativity of the CAP and additional ECochG findings point to a neural origin in this patient group (Santarelli et al., 2015b).

16. Are cochlear implants also successful with these patients?

Seven of the patients in the study I just mentioned underwent unilateral cochlear implantation (Santarelli et al., 2015b). CI outcomes were positive in all patients, though variable, with improvement in speech recognition scores in quiet and in noise. In quiet, speech recognition improved from 0% pre-CI to 50-90% post-CI in 5 patients and more modest improvement was observed in two patients. Speech perception testing in background noise indicated significant increases in open-set word recognition after 1 year of CI use in all patients tested. Electrically evoked compound action potentials (eCAPs) and auditory brainstem responses (eABR) obtained post-CI indicated present eABRs where ABR was absent pre-CI. The eCAPs post-CI were absent, consistent with involvement of auditory nerve fibers in this patient group.

In summary, cochlear implantation is recommended as a viable management option with significant improvements in test results, supporting positive outcomes, despite involvement of the auditory nerve. Post-CI testing demonstrated improved hearing thresholds, speech perception, and synchronous activity in the auditory brainstem pathways.

17. Whew, we’ve covered a lot, some of it new to me, and I’m running low on questions. How about a quick summary?

Sure, we’ve spent quite a bit of time discussing genotype and phenotype related to variants found in two genes (OTOF, OPA1). We also have noted that variants in many other genes have been associated with different types of AN/AS.

It is important to understand that, even when discussing specific genes, we expect considerable differences among patients. This can be related to multiple factors, including the specific variant and its impact on the production of the related protein as well as interactions with other genes and DNA sequences. Variation is seen across all types of genetic disorders, not only those related to hearing or AN/AS.

While considerable information has accumulated related to genetic hearing loss and association of hearing loss characteristics with genotype, there remain unidentified genes. Therefore, if a patient has a negative test result, one cannot conclude that their disorder is not genetic. It may just mean that the genetic variants underlying a patient’s condition have not yet been discovered and described. Genetic testing across many patients with AN/AS is needed to continue to identify new genetic variants associated with AN/AS.

18. What about phenotyping?

In-depth phenotyping involving audiology, genetics, neurology, ophthalmology, and other specialties enables accurate diagnosis of AN/AS and, in some cases, identification of sensory, synaptic or neural disease mechanisms. Understanding the characteristics of AN/AS and how various test results are associated with different genes, and different variants within genes, is achieved through sensitive and accurate phenotyping. Careful, in-depth evaluation of well-defined patient cohorts contribute to the ability to accurately localize the site of the disorder – in the context of our discussion, we have focused on distinguishing AN and AS. Using a combination of genetic analysis, clinical measures for accurate diagnosis, and advanced physiologic and psychophysical approaches will move our knowledge base forward.

Transtympanic ECochG testing provides a powerful approach to accurately defining involved physiologic processes in AN/AS, understanding differences among types of AN/AS, and supports informed management of patients. This is highlighted in the work by Dr. Rosamaria Santarelli and the reader is referred to those references for insight into the value of thorough evaluation using physiologic and behavioral approaches. Transtympanic ECochG is more widely used in some practices and areas of the world than others. The invasive nature of this technique and the requirement for anesthesia are limitations to its use in some clinical settings. Furthermore, in some practices ECochG testing may be reserved for assessment prior to cochlear implantation. As Santarelli et al. (2015a, 2015b) note, post-CI electrical responses also provide insight into outcomes and information that can be useful in considering expectations.

Imaging studies provide information helpful in differential diagnosis and separating AN/AS from inner ear malformations and physical characteristics of the auditory nerve. In some cases, these conditions may show clinical audiologic test results consistent with AN/AS but can be distinguished based on anatomical abnormalities. Absent or hypoplastic auditory nerves are not uncommon (Buchman et al., 2006) and these cases can resemble AN/AS when cochlear active processes are not affected and OAEs are present. Audiological management in these patients can be challenging since a cochlear implant is dependent on function of the auditory nerve that is compromised when the nerve is hypoplastic or absent (Teagle et al., 2010).

19. Should I expect to see changes in audiologic results over time?

While many patients demonstrate stable physiologic responses and behavioral audiometric thresholds over many years, changes in hearing ability in patients with AN/AS is observed. Several factors can contribute to changes over time.

Progressive worsening of hearing ability is observed in some patients, though it is not characteristic of all patients. As noted in the discussion of patients with OPA1 genetic variants underlying their AN, a characteristic of this and many ther neuropathies is progression of the disease and related function over time. Other examples include patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease or Friedreich ataxia.

Loss of functional cochlear active processes/OHC function, measured by OAEs and CM, over time is reported in some patients. While changes in OAEs are confounded by presence of middle-ear problems, loss of OAEs over time in patients with normal middle-ear function has been documented in a number of studies (e.g., Deltenre et al., 1999; Kitao et al., 2018; Thorpe et al., 2002).

AN/AS is associated with fluctuation in hearing ability in some patients. An example discussed above was in relation to temperature sensitivity associated with variants in the OTOF gene. It is important to note that there are multiple causes and underlying conditions that could contribute to fluctuation in auditory function, many as yet unidentified. A key factor in clinical management is listening to patient and parent reports of changes and appropriately incorporating this information into management planning.

20. A lot of great information. Any closing comments?

Sure, I think an important factor to remember is that the observed variation among patients underscores the importance of developing further knowledge and including genetic analysis in evaluations to allow clinicians to accurately distinguish among the various forms of AN/AS. Progress in this area will continue with additional discoveries in genetics, improved sensitivity of physiologic responses, and further exploration of sensitive psychophysical tasks such as those related to temporal resolution. Auditory cortical late-latency responses may provide insight into functional abilities. Hopefully, future research and clinical assessment will see greater utilization of novel stimuli and paradigms, more sensitive approaches, and development of clinically feasible methods that include these advances. Even within various forms of AN/AS, we expect that variation will exist and we will need to understand the range of variation and contributing factors.

Advances in understanding various forms of AN/AS should guide us towards a better understanding of those characteristics that may derive benefit from amplification, versus cochlear implants, versus those in need of supportive intervention without technology. Guidelines and protocols for determination of need for and success with hearing aids, FM systems, cochlear implants are needed, as well as the ability to predict who will develop speech/language with minimal intervention despite poor neural synchrony. Patient and parent education is critical as we learn more about AN/AS and use our knowledge to guide our patients and their families in making informed decisions.

References

ARO. (2024). Otoferlin gene therapy press release. https://aro.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/ARO-press-release-Otoferlin-gene-therapy-FINAL-1_30_24.pdf

Berg, A. L., Spitzer, S. B., Towers, H. M., Bartosiewicz, C., & Diamond, B. E. (2005). Newborn hearing screening in the NICU: Profile of failed auditory brainstem response/passed otoacoustic emission. Pediatrics, 116(4), 933–938.

Berlin, C. I., Bordelon, J., St. John, P., Wilensky, D., Hurley, A., Kluka, E., & Hood, L. J. (1998). Reversing click polarity may uncover auditory neuropathy in infants. Ear and Hearing, 19(1), 37–47.

Berlin, C. I., Hood, L. J., Morlet, T., Wilensky, D., Li, L., Rose-Mattingly, K., Taylor-Jeanfreau, J., Keats, B. J. B., St. John, P., Montgomery, E., Shallop, J. K., Russell, B. A., & Frisch, S. A. (2010). Multi-site diagnosis and management of 260 patients with auditory neuropathy/dys-synchrony (auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder). International Journal of Audiology, 49(1), 30–43.

Buchman, C. A., Roush, P. A., Teagle, H. F., Brown, C. J., Zdanski, C. J., & Grose, J. H. (2006). Auditory neuropathy characteristics in children with cochlear nerve deficiency. Ear and Hearing, 27(4), 399–408.

Deltenre, P., Mansbach, A. L., Bozet, C., Christiaens, F., Barthelemy, P., Paulissen, D., & Renglet, T. (1999). Auditory neuropathy with preserved cochlear microphonics and secondary loss of otoacoustic emissions. Audiology, 38(4), 187–195.

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (2007). Year 2007 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics, 120(4), 898–921.

Kaga, K., Nakamura, M., Shinogami, M., Tsuzuku, T., Yamada, K., & Shindo, M. (1996). Auditory nerve disease of both ears revealed by auditory brainstem responses, electrocochleography, and otoacoustic emissions. Scandinavian Audiology, 25(4), 233–238.

Kitao, K., Mutai, H., Namba, K., Morimoto, N., Nakano, A., Arimoto, Y., Sugiuchi, T., Masuda, S., Okamoto, Y., Morita, N., Sakamoto, H., Shintani, T., Fukuda, S., Kaga, K., & Matsunaga, T. (2019). Deterioration in distortion product otoacoustic emissions in auditory neuropathy patients with distinct clinical and genetic backgrounds. Ear and Hearing, 40(1), 184–191.

Marlin, S., Feldmann, D., Nguyen, Y., Rouillon, I., Loundon, N., Jonard, L., Bonnet, C., Couderc, R., Garabedian, E. N., Petit, C., & Denoyelle, F. (2010). Temperature-sensitive auditory neuropathy associated with an otoferlin mutation: Deafening fever! Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 394(4), 737–742.

Morlet, T., Parkes, W., Pritchett, C., Venskyis, E., DeVore, B., & O’Reilly, R. C. (2023). A 15-year review of 260 children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder: I. Demographic and diagnostic characteristics. Ear and Hearing, 44(5), 969–978.

Moser, T., & Starr, A. (2016). Auditory neuropathy—Neural and synaptic mechanisms. Nature Reviews Neurology, 12(3), 135–149.

Rodriguez-Ballesteros, M., Reynoso, R., Olarte, M., Villamar, M., Morera, C., Santarelli, R., Arslan, E., Meda, C., Curet, C., Volter, C., & Smith, R. J. H. (2008). A multicenter study on the prevalence and spectrum of mutations in the otoferlin gene (OTOF) in subjects with nonsyndromic hearing impairment and auditory neuropathy. Human Mutation, 29(6), 823–831. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.20708

Santarelli, R., del Castillo, I., Cama, E., Scimemi, P., & Starr, A. (2015a). Audibility, speech perception, and processing of temporal cues in ribbon synaptic disorders due to OTOF mutations. Hearing Research, 330, 200–212.

Santarelli, R., Rossi, R., Scimemi, P., Cama, E., Valentino, M. L., La Morgia, C., Caporali, L., Liguori, R., Magnavita, V., Monteleone, A., Biscaro, A., Arslan, E., & Carelli, V. (2015b). OPA1-related auditory neuropathy: Site of lesion and outcome of cochlear implantation. Brain, 138(3), 563–576.

Santarelli, R., Scimemi, P., Costantini, M. M., Domínguez-Ruiz, M., Rodriguez-Ballesteros, M., & del Castillo, I. (2021). Cochlear synaptopathy due to mutations in OTOF gene may result in stable mild hearing loss and severe impairment of speech perception. Ear and Hearing, 42(6), 1627–1639.

Snoeckx, R. L., Huygen, P. L., Feldmann, D., Marlin, S., Denoyelle, F., Waligora, J., Mueller-Malesinska, M., Pollak, A., Ploski, R., Murgia, A., Orzan, E., Castorina, P., Ambrosetti, U., Nowakowska-Szyrwinska, E., Bal, J., Wiszniewski, W., Janecke, A. R., Nekahm-Heis, D., Seeman, P., Bendova, O., … Van Camp, G. (2005). GJB2 mutations and degree of hearing loss: A multicenter study. American Journal of Human Genetics, 77(6), 945–957.

Starr, A., Picton, T. W., Sininger, Y., Hood, L. J., & Berlin, C. I. (1996). Auditory neuropathy. Brain, 119(3), 741–753.

Starr, A., Sininger, Y., Winter, M., Derebery, M. J., Oba, S., & Michalewski, H. J. (1998). Transient deafness due to temperature-sensitive auditory neuropathy. Ear and Hearing, 19(3), 169–179.

Teagle, H. F., Roush, P. A., Woodard, J. S., Hatch, D. R., Zdanski, C. J., Buss, E., & Buchman, C. A. (2010). Cochlear implantation in children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. Ear and Hearing, 31(3), 325–335.

Thorpe, R. K., Azaiez, H., Wu, P., Wang, Q., Xu, L., Dai, P., Yang, T., Schaefer, G. B., Peters, B. R., Chan, K. H., & Smith, R. J. H. (2022). The natural history of OTOF-related auditory neuropathy spectrum disorders: A multicenter study. Human Genetics, 141(5–6), 853–863.

Varga, R., Avenarius, M. R., Kelley, P. M., Keats, B. J., Berlin, C. I., Hood, L. J., Morlet, T. G., Brashears, S. M., Starr, A., Cohn, E. S., Smith, R. J. H., & Kimberling, W. J. (2006). OTOF mutations revealed by genetic analysis of hearing loss families including a potential temperature-sensitive auditory neuropathy allele. Journal of Medical Genetics, 43(7), 576–581.

Citation

Hood, L. J. (2025). 20Q: Auditory neuropathy and auditory synaptopathy - genotyping and phenotyping. AudiologyOnline, Article 29199. Available at www.audiologyonline.com