From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

“Up-in-5—Down-in-10.” Sound familiar? Other than “Don’t run with scissors,” there probably is no guideline more ingrained in the minds of audiologists. So much so, that some of us feel a little guilty when we go “Down-in-5.”

Now, I mentioned that this audiometric bracketing procedure is a guideline, and it is, gaining steam when it was endorsed by Carhart and Jerger in 1959. You’ll find this approach recommended in most every text book chapter on audiometric testing and in documents from the ASHA. Guidelines, however, are just that—recommendations. Like drinking white rather than red wine when eating fish. But, as some of you know, the “Up-in-5—Down-in-10” approach is not just a guideline, it’s also part of a standard regarding audiometric testing (ANSI S3.21-2004; R2009).

Do we need both guidelines and standards regarding the practice of clinical audiology? At least one group of audiologists thinks so, and that’s the members of Audiology Practice Standards Organization (APSO). This organization was created a few years ago with the purpose of developing, maintaining, and promoting national standards for the practice of audiology; they are independent from other audiology organizations. The APSO recently published their first standard: General Patient Intake. You can find it at their website: www.audiologystandards.org

It’s only fitting that the person to tell us about the APSO in this month’s 20Q article is their current president, Jenne Tunnell, AuD, PASC. She is manager of the Mayo Clinic Health System Audiology for Southwest Minnesota. In addition to her APSO duties, she serves as the Chair Elect of AAA’s Academic and Professional Standards Council, and recently was the Chair of the AAA’s ABA. She is a past president of the Minnesota Academy of Audiology, and a member of the much-acclaimed 2012 JFLAC cohort. Most of us know Jenne in her role as the co-host of the AudiologyTalk podcast.

While some of you might not be fans of “standards,” Jenne’s 20Q article presents a strong case for why they are good for a profession. The way I see it, if new practice standards are well thought out, we can assume that they will identify areas where audiologic services can be improved, and determine evidence-based best practices. If compliance follows, in the end our patients will be better served. The patients also will know that they are receiving services that have been verified. All this seems like a good thing.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Why We Need an Audiology Practice Standards Organization

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Explain the difference between a guideline and a standard.

- Discuss the purpose of the Audiology Practice Standards Association and list some of its current activities.

- State why audiologists may consider membership in the Audiology Practice Standards Association.

Jenne Tunnell, AuD

Jenne Tunnell, AuD

1. I have to admit, I didn’t even know we had a practice standards organization?

I’m sure you’re not the only one. We're a fairly new organization. The Audiology Practice Standards Organization (APSO) was created in 2017 to develop, maintain, and promote national standards for the practice of audiology that are based on current evidence, reflect best practices in the profession and are universally adopted by practitioners. Simply put, APSO is an organization created to develop and maintain practice standards for the profession. This is, of course, an organization that intends to work with all the national and state organizations, not to replace or compete with any of them. We are solely focused on practice standards development with the intention to make true standards which are open access to all colleagues and for which everyone has the opportunity to participate.

2. What brought you all together?

John Coverstone and I were broadcasting the 85th episode of the AudiologyTalk podcast at the 2017 conference of the American Academy of Audiology (AAA) in Indianapolis. It was Day 2 of our broadcast, and we invited Lindsey Jorgensen from University of South Dakota, and Gail Whitelaw from The Ohio State University as guests to talk about practice standards, best practices, and standards of care for audiology. As we were talking, we realized that the lack of evidence-based published standards was a gap in our profession. We also noted that evidence-based published standards should be developed by an entity that is independent of other audiology organizations. It also needs to be accessible to all. We decided then and there to do something about it. After all, what’s the point in complaining about something if you aren’t prepared to offer a solution?

3. You say “standards.” But don’t we already have guidelines? And what is the difference?

There can be some overlap, but they are most definitely different. Collins Dictionary defines a standard as “…the usual thing that is done in a particular situation.” Webster’s definition states: “to bring into conformity with standard.” A good working definition for our purposes in audiology is that standards are a set of principles that ensure we are providing high-quality audiology care and that provide criteria for evaluating care. Standards are also important if a legal dispute arises over the quality of care provided a patient.

Guidelines, on the other hand, are reccommendations for how we perform our work. For example, practice guidelines tell us how to perform clinical activities.

I like to use a cooking analogy: A cooking standard might state that you should eat healthy foods and prepare foods in a clean and safe environment. Cooking guidelines would detail what are healthy foods, in what proportions they should be consumed, and in what environment they should be prepared. Best practices would indicate that you should use fresh ingredients, instead of preserved ingredients, in order to achieve optimal results.

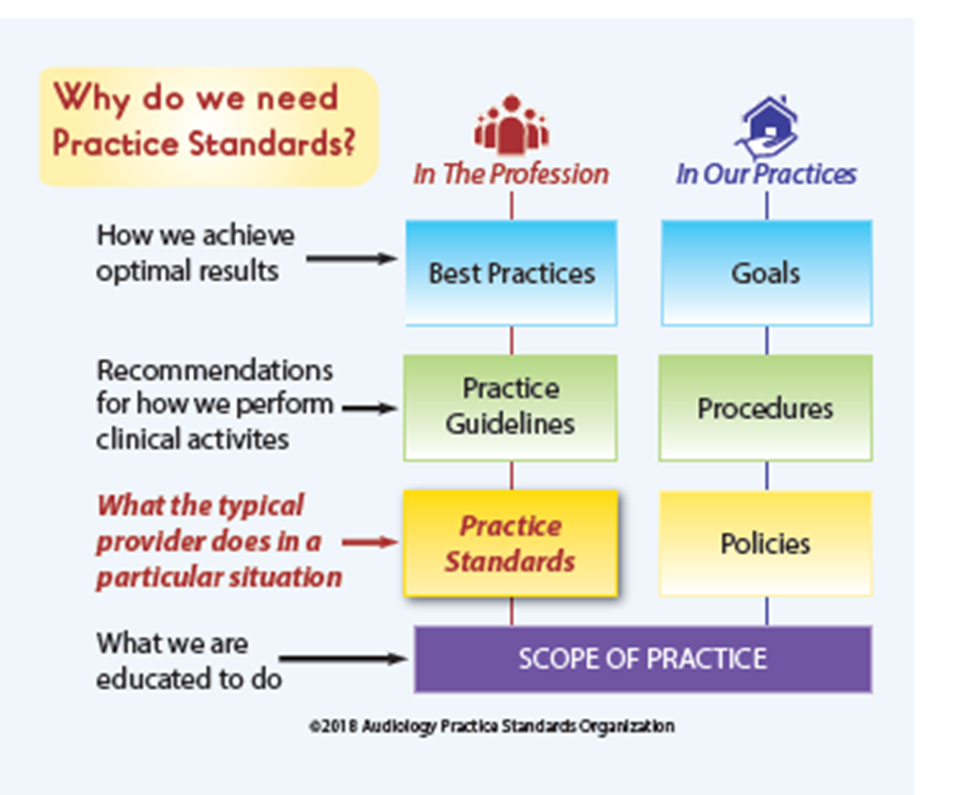

Figure 1 illustrates how standards cascade to guidelines and eventually manifest in our clinical behavior as best practices. Conceptually, standards and guidelines have a similar relationship to policies and procedures, in which case a policy offers broad guidance and the procedure provides more directive guidance.

Figure 1. Why we need practice standards.

4. Do we really need standards?

Practice standards are the foundation for all areas of clinical practice. Most professions established their practice standards many years ago and update them regularly. Practice standards, along with clinical guidelines, help providers to have a quick reference for their clinical protocols and decision-making without needing to periodically search through new evidence and update their practices accordingly. They also serve as a guide for clinical educators to update their curriculum and ensure that they are teaching to the most current evidence.

Practice standards also offer a defense of the profession. These threats to the profession may come from many different sources, including encroachments on scope of practice, lawsuits involving practice methods, or outside entities failing to recognize the necessity and value of audiology services. A well-designed practice standard, based in evidence and published only after widespread review from the entire profession, helps defend against most threats to the profession. Clinical practice standards have been used to support an expert witness testimony, impeach an expert witness, defend practitioners who adhere to them, and suggest that deviance from the practice standards indicates deviation from the standard of care. In the end, clinical practice standards are strongest when based in evidence, developed by recognized experts in the area of practice, maintained and current, and when followed by the individual accused of negligence. Practitioners ignoring accepted practice guidelines run the risk of being found negligent by legal proceedings.

5. Are there examples of other healthcare professions who have come up against issues because of the lack of practice standards?

There are serious repercussions that can come from lack of clinical practice standards. The more serious of these are the legal implications. Audiology has largely flown under the legal radar, but that all is likely to change, especially given the increase in demand for our services. Clinicians will be seeing more patients, such as the Baby Boomer generation, who are consumer-oriented, and are more likely to become litigious if unhappy with care. The lack of established clinical practice standards will mean that the judge, not the profession, will decide what is a reasonable standard of care. The establishment of published standards of practice that are based on scientific evidence and peer-reviewed will mean that we will be safeguarded in these situations. We will be able to reference these universally agreed-upon, minimum clinical practice standards for all audiologists when needed.

There are two early precedents which helped define the legal definition of standard of care as it is used today. Both are taken from the article, The Standard of Care: Legal History and Definitions: the Bad and Good News (Moffett & Moore, 2011). This article was written specifically for emergency medicine physicians but it is an interesting read regarding the history of standard of care interpretation in the courts.

The first precedent Moffett and Moore discuss arose entirely outside medicine. In 1932, a tugboat named the T.J. Hooper had been caught in a storm and the two barges it was transporting sunk. The owner of the tugboat was sued by the owners of the barges, who stated that the T.J. Hooper was not safe to be at sea because it did not have a radio to receive storm warnings. They also asserted that it was “customary” for tugboats to have a radio and that the T.J. Hooper could have avoided the storm if it had a radio. At the time, the customary definition of the legal standard was essentially that - what is typically done is what is considered to be standard. The judge in the case found in favor of the barge owners, but not because of custom. His decision, in fact, stated that it was not customary for tugboats at the time to have a radio receiver. However, he asserted that the practice was “reasonable,” meaning that the owners of the T.J. Hooper would have been prudent to have a radio and therefore could be held liable. This was an important precedent because it failed to excuse a customary practice. As worded in Justice Learned Hand’s written statement, “…a whole calling may have unduly lagged in the adoption of new and available devices. It never may set its own tests, however persuasive be its usages. Courts must in the end say what is required; there are precautions so imperative that even their universal disregard will not excuse their omission.”

6. But I was asking about healthcare professionals, not tugboats.

I’m getting there. Justice Hand’s statement was quoted in a 1974 decision by the Supreme Court of Washington, which is the second precedent described by Moffett and Moore. In this case, a patient sued her ophthalmologist after going blind from glaucoma. The ophthalmologist won both the initial trial and first appeal based on expert testimony that the patient was under 40 years of age and the incidence of glaucoma in this group was only 1 in 25,000. Therefore, it was not standard to test patients under 40 with tonometry. The Supreme Court, though, decided that the test was inexpensive and harmless to the patient and should have been offered. This is an important decision because it also held the defendant liable to practices that were not commonly performed at the time. The court established a bar of reasonable prudence, rather than average practice.

7. So you are saying that “average” practice might not be good enough?

That’s right. Both these cases established that, while consideration is provided to customary practices of a profession, the standard of care does not make average practice the definitive factor in determining negligence. What common practices do you employ which omit procedures that are accessible, harmless, inexpensive, and brief, and yet may significantly improve outcomes for your patients?

Future decisions by U.S. courts served to further define the standard of care in medicine, including establishing minimal competence as the standard, not average level of skill. As Moffett and Moore point out, a standard of “average” competence would leave 50% of practitioners below the standard. Courts have also held that poor outcomes are not a measure of competence, as a physician is not an insurer of health or a guarantor of results. Instead, the standard is the level of skill generally possessed by others practicing in the field under similar circumstances.

Aside from legal implications, consider this: If we don’t have clinical practice standards, how do we motivate increased reimbursements or policy changes? How can we talk about outcomes or best practices, when we haven’t established what the minimum standards of practice actually are?

8. Okay, I get the standards thing, but why do we need another audiology organization? Seems we have more than our share for a relatively small profession.

The reality of the situation is that there are several organizations that represent audiology, and no single organization will be representative of all audiologists. APSO is apolitical, independent and open to all audiologists regardless of affiliation or membership in our organization. This offers the only inclusive mechanism available in our profession today. Additionally our purpose is clear; we are focused on clinical practice standards, and our work will not be diluted by other issues. Think about this for a moment: ANSI exists as an apolitical organization that develops test standards. APSO exists to develop clinical practice standards. APSO is, in essence, the ANSI of Practice Standards, which is essential in ensuring the quality of services that audiologists deliver.

9. You mention membership. Does that mean that there are membership dues to belong to APSO?

Yes there are. Membership dues go towards the creation of infrastructure, the development of clinical practice standards, communications and operational costs associated with a not for profit business. The membership fee is a nominal $50 for practicing audiologists and $35 for students enrolled in an accredited program. We also have excellent sponsorship opportunities.

10. What do I get for an APSO membership?

Membership entitles you to receive real-time updates on the development of clinical practice standards, early registration to join standards-setting working groups, and the satisfaction that you are part of one of the most significant agents of change in our profession in decades.

11. Count me in. Back to standards - who decides what the standards will be?

Subject matter experts make these decisions with input from the audiology community at large. As a stakeholder, you have the opportunity to provide input in multiple formats.

12. What happens if I don’t follow a standard?

First, we are talking about minimum clinical practice standards. There’s no penalty, but do you really want to practice outside a minimum clinical practice standard? if someone looks at your practice, they are going to know that you aren’t meeting minimum standards. You would be at the same risk you are now so we aren’t increasing risk—we are decreasing it.

13. How exactly does your group create a standard?

APSO uses the following process for the development of evidence-based clinical practice standards:

- APSO approves development of clinical practice standards for an area of interest.

- APSO performs selection and recruitment of subject matter experts to form two working groups.

- APSO facilitates one of two working groups tasked with reviewing: Current standards of care; Scientific evidence related to the subject matter; Strength of evidence; Grade rating

- Working groups then create an algorithm/flowchart for the area of interest: Patient presents; History; Testing/results/pathways to diagnosis; Recommendations and management; Referrals; List CPT codes that would be appropriate

- First draft is provided to the APSO Board of Directors for edits.

- Select review is solicited by the second group of subject matter experts who form the second working group.

- The second draft is formulated by the second working group.

- The draft is then released for a scheduled national peer review. Comments are solicited and collated.

- Results of the peer review are reviewed and clinical practice standards revised accordingly. Comments that do not influence revision are documented by reviewers to specify the rationale behind the decision.

- Final draft is approved by APSO and sent to legal counsel for review.

- Legal counsel reviews and approves the clinical practice standards for publication.

- Publication of clinical practice standards on APSO website.

- APSO conducts regular reviews of relevant research along with any new evidence and revises the clinical practice standards as necessary.

14. How did you come up with this process for developing standards?

Ironically, there are no published standards that outline how to develop a standard. Our inaugural Board members dedicated many hours of research looking at how parallel professions such as optometry and nursing have developed their clinical practice standards. We then developed a comprehensive and rigorous pathway built on scientific evidence, peer review, and one that is inclusive of all stakeholders.

15. What standards have you published so far?

I’m so glad you asked! We recently published our first clinical practice standard: General Patient Intake Standard. You can find it here at our website: www.audiologystandards.org

16. Do I have to be a member in order to access the published standards?

APSOlutely not! Obviously, we hope that everyone will become members, but access to our standards is open to all audiologists (and any other interested parties).

17. Who decides which standards need to be worked on next?

The Board of Directors compiles a list of suggestions and involves membership in ranking these in terms of priority. Stakeholders are solicited to submit suggestions and ideas via surveys. We run the suggestions through a rubric and see what floats to the top.

We will most definitely review clinical practice standards as research evolves and provides evidence that requires us to update them. How often that occurs will vary, and will likely depend on the subject matter. The Board will work out a regular review cycle once we have more practice standards completed and published.

18. What’s next for APSO?

We are currently organizing the first working group for Hearing Aid Fitting and Verification. This will definitely be an enormous task, and one which we will need everyone in our profession to weigh in on.

19. Who’s on the APSO Board?

Here is a list of our 2020 Board of Directors:

- Jenne Tunnell, AuD - President

- Amit Gosalia, AuD - Past President

- Patricia Gaffney, AuD - Vice President

- Sarah Curtis, AuD - Secretary

- A.U. Bankaitis, PhD - Treasurer

- Jason Galster, PhD

- Lindsey Jorgenson, AuD, PhD

- Emily McMahan, AuD

I would like give a special shout out to Jason Galster, who contributed to this article, as well as our Founding Father and current Executive Director, John Coverstone, who allowed me to plagiarize some of his literature review. Thank you Jason and John!

20. Who should get involved with APSO and how?

I encourage every audiologist to get involved. After all, just as ANSI is helping you with calibrating your equipment, you are calibrating how you practice audiology. There are multiple ways to get involved, such as joining a working group when notified of a clinical practice standard with which you have a special interest or experience, providing feedback on surveys, reviewing proposed standards that come up for public comment, offering financial support, or running for the Board of Directors. Visit www.audiologystandards.org for more information. Please reach out to me or any of the Board members if you have any questions or would like to get involved!

References

American Nurses Association. (2016). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice, 2nd ed. Silver Spring Maryland: American Nurses Association.

Federation of State Medical Boards. (2005). Assessing scope of practice in health care delivery: Critical questions in assuring public access and safety. Retrieved from https://www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/2005_grpol_scope_of_practice.pdf

Health Resources and Services Association, Bureau of Primary Health Care. HRSA policies and procedures template for clinics. In US Health Resources & Services Administration Online. Available at https://bphc.hrsa.gov

Mackey, T.K., & Liang, B.A. (2011). The role of practice guidelines in medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor: American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, 13(1), 36-41.

Mello, M.M. (2001). Of swords and shields: the role of clinical guidelines in medical malpractice litigation. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 149(3), DOI: 10.2307/3312867

Moffett, P., & Moore, G. (2009). The standard of care: legal history and definitions: the bad and good news. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 12(1), 109-112.

Strauss, D., & Thomas, J.M. (2009). What does the medical profession mean by “Standard of care?”Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27(32), e192–e193.

Walker, R.D., Howard, M.O., Labert, M.D., & Suchinsky, R. (1994). Medical Practice Guidelines. Western Journal of Medicine, 161(1), 39-44.

Citation

Tunnell, J. (2020). 20Q: Why we need an audiology practice standards association. AudiologyOnline, Article 26955. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com