From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

If you go from audiology clinic to audiology clinic, you’ll probably find that all audiologists have a similar basic test battery: air conduction, bone conduction, speech audiometry and immittance. Beyond the basic battery, however, we tend to see a fair amount of variety in the tests that are conducted. Maybe electrophysiologic testing? Maybe auditory processing evaluations? Special testing for tinnitus?

In audiology social media, we often see posts with clinical questions headlined, “Hey There Vestibular Audiologists.” I suspect that indeed, there are audiologists who refer to themselves as vestibular audiologists. Our 20Q author this month, however, suggests that in a limited way, maybe most all clinical audiologists could be vestibular audiologists! No, this doesn’t mean that you’ll need to spend $100,000 on rotary chair equipment. Rather, your investment likely will be no more than the cost of a bottle of good wine. This will be for the purchase of a ruler, a stopwatch, and a special step stool.

Joining us this month at 20Q is David Jedlicka, AuD, staff audiologist at the Pittsburgh VA Healthcare System, and Clinical Instructor at the University of Pittsburgh. In addition to his patient-care duties, Dr. Jedlicka serves as a preceptor for AuD students during their clinical coursework and mentor for students completing clinically-based research projects.

Dr. Jedlicka is Chair of the AAA membership committee, was named to the AAA Jerger Future Leaders of Audiology, and recently received the Academy’s Early-Career Audiologist award. He also recently was selected for the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Health and Rehabilitation Science Distinguished Alumni Award. In addition to his many other professional organizational positions, he serves as the President of the Association of VA Audiologists.

While Dave’s professional achievements over a ten-year span have been pretty remarkable, his greatest claim to fame may go back to his AuD student days at Pitt. Pitt basketball has a huge cheering section fondly known as “The Zoo.” The Zoo repeatedly has been noted as being one of the most formidable student cheering sections in college basketball. For three years, Dave was President of The Zoo (AKA, Zoo Keeper; or as a local newspaper called him, “King of the Zoo”). During his tenure, The Zoo was profiled in the Wall Street Journal and featured on ESPN. I’m thinking that if Dave can lead a coordinated cheer for thousands of rowdy fans, he just might be able to rally a few audiologists to add vestibular screening to their clinical test protocol!

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Why All Audiologists Should be Administering Balance Screenings

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Identify effective balance screening assessments to use in the audiology clinic.

- Create clinical instructions to increase student confidence in administering and assessing fall risks.

- List specialty care disciplines that should be involved in a fall risk assessment team.

David Jedlicka

David Jedlicka1. Don’t we all already agree that vestibular assessments are an important part of an audiologist’s scope of practice?

Maybe so, but my observations tell me that functional balance tests are often overlooked. Like many audiologists, I first looked at our role in the balance world through the lens of completing objective diagnostic vestibular tests such as VNG, rotational chair, vHIT, VEMPs, and computerized dynamic posturography testing. While these tests are vital for audiologists specializing in vestibular assessment, functional balance testing can serve as a quick way to screen for vestibular and balance disorders, document fall risk, and gain a better understanding of a patient’s “real world” limitations.

2. You’re referring to testing that primarily would be done by audiologists that specialize in vestibular practice?

Not at all. Functional balance tests can be completed by any audiologist, audiology assistant, or audiology student. The beauty of these tests is that they are easy to administer and score, and most were developed by people who are not audiologists. The idea is that the tests can be administered by almost anyone in the healthcare field. Simple scoring systems make it easy to determine if a patient should be considered as a “fall risk”.

In addition to this, audiologists who treat Medicare Part B patients under the Quality Payment Program (QPP) have two ways to demonstrate quality reporting. One of the more common ways for audiologists to participate in quality reporting is through using the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). There are six measures in this program that audiologists must meet, including measure #154 Fall Risk Assessment. The American Academy of Audiology (AAA) and American Speech, Language and Hearing Association (ASHA) have resources available to help audiologists understand how to meet the falls risk guidelines (See: AAA Resources, ASHA Resources). Currently, audiologists are not reimbursed for completing fall risk assessments. While that is something that we all hope will change in the future, that does not mean that these assessments should be ignored.

3. Would simply adding some form of balance questionnaire to the patient’s case history form be adequate?

This is the same question we asked ourselves when we were trying to find better ways to screen our audiology patients for potential balance issues. We certainly do have some scales available—the most popular probably is the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) (Jacobson & Newman, 1990). Luckily, one of our audiologists, Dr. Cara Michaux, has completed some amazing work evaluating several aspects of incorporating balance screenings in the clinic; including looking at the use of questionnaires. The DHI is a very commonly used measure in the balance world and provides good information regarding a person’s self-perceived balance handicap. We know, however, that patients are often not the best self-reporters, and this applies to self-reports about balance ability as well. Dr. Michaux’s research found that there wasn’t a strong correlation between overall DHI score and performance on balance screenings. Although the overall DHI didn’t predict balance screening performance, Dr. Michaux was able to identify that 8 of the 25 questions on the DHI were sensitive to predicting when a patient would be considered a fall risk. They are as follows (numbered according to the DHI):

Q2. Because of your problem, do you feel frustrated?

Q5. Because of your problem, do you have difficulty getting into or out of bed?

Q8. Does performing more ambitious activities such as sports, dancing, household chores (sweeping or putting the dishes away) increase your problems?

Q10. Because of your problem have you been embarrassed in front of others?

Q11. Do quick movements of your head increase your problem?

Q15. Because of your problem, are you afraid people may think you are intoxicated?

Q19. Because of your problem, is it difficult for you to walk around your house in the dark?

Q21. Because of your problem, do you feel handicapped?

Despite this intriguing information, you won’t see many people on the VA Pittsburgh Fall Risk Team discussing DHI scores. Many hospitals have their own fall risk criteria and our VA is no exception. Currently, the Pittsburgh VA Fall Risk Team uses the Morse Fall Scale (Morse, Morse, & Tylko, 1989) to designate inpatients as being at risk for a fall incident.

4. I’m going to want to hear more about that Fall Scale, but first, what other professionals are part of this Fall Risk Team?

The Fall Risk Team is comprised of very diverse team members, in total there are around 25 members. The most important members of this group are the nurses. We are fortunate to have a nurse representative from every inpatient unit and our community living center as part of the team. They are the professionals who complete most of the Morse Fall Scale evaluations, which ultimately determines if the patient is classified as a fall risk. Additional members include physicians, physical therapists, patient safety coordinators, and audiology (represented by Dr. Cara Michaux).

5. What role does audiology play on the Fall Risk Team?

It’s probably not surprising that our main role is to ensure that patient’s audiologic needs are being met. We review the cases and will discuss the patients with the team to provide education to other disciplines, determine if the patient needs to have an audiometric evaluation, but most of the time we determine if comprehensive balance assessments are required based on what is known about the patient. We always start with a chart review because the Fall Risk Team meets monthly to discuss any recent fall incidents that have occurred in the hospital. Team goals are to minimize the number of falls and to prevent future falls by improving policies and procedures. Each incident report is discussed, and audiology often works in conjunction with physical therapy to determine if further assessment and possible treatment are warranted. The team also ensures that the patient is classified as a fall risk in the medical record and the Morse Fall Scale is reassessed.

6. Why was the Morse Fall Scale selected by the Fall Risk Team?

The Morse Fall Scale is widely researched and has been proven to be a great measure for determining when a patient is a fall risk. However, the Morse Fall Scale was designed for inpatient assessment as it is completed by a medical team member without patient input. So even though this is a questionnaire-based assessment, the questions are aimed to be objective and not biased by patient perception.

7. If the Morse Fall Scale is for inpatient use, are there other balance assessments that your clinic uses for outpatients?

Most of the patients that we treat in our clinic are outpatients that are primarily being seen due to hearing difficulty. In our case history form, we ask a very broad question about if the patient is having any issues with their balance. Obviously, patients with significant dizziness or vertigo complaints are referred for a full vestibular evaluation.

However, many patients report more mild or general balance complaints that we would like to address during the visit. Like with most appointments at a busy clinic, we only have a limited amount of time to complete everything that is required with our patients. So, for our clinic, we need balance screenings that are reliable but also fast. Most importantly, we need every audiologist in our clinic to be able to administer these tests to ensure patient safety.

The two tests that we routinely administer are the Berg Balance Scale (Berg, Wood-Dauphinee, Williams, & Maki, 1992) and the Timed Up and Go Test (Podsiadlo & Richardson, 1991). The audiologists in our clinic who do not specialize in vestibular assessments tend to prefer the Timed Up and Go Test as it simply requires the patient to go from a sitting to standing position, walk 10 feet, turn around, and sit back down. If the patient takes 13.5 seconds or longer to complete this task, they are classified as being a fall risk (Barry, Galvin, Keogh, Horgan, & Fahey, 2014). In addition to being appropriate for fall risk screening, the Timed Up and Go Test can also be used as a predictor of falls based on age and the time required to complete the test (Shumway-Cook, Brauer, & Woollacott, 2000).

The Berg Balance Scale consists of 14 static and dynamic test items and gives the test administrator a better idea of where a patient is most at risk for falling. For example, we might learn that a patient is not at risk when walking on flat, non-carpeted surfaces, but actions such as climbing stairs or bending at the waist is an action that places the patient at risk.

Since the Berg Balance Scale is a more detailed test, it does take longer. That is the main reason why some clinicians feel more comfortable using the Timed Up and Go Test. Ultimately, both tests allow the administrators to determine if a patient is at risk for falling.

8. Are there any other tests that audiologists may find useful to incorporate into their practice?

There is a wide variety of functional balance assessment and fall risk screenings available. Most of these are very well researched and are worthy of consideration for inclusion to anyone who is interested in implementing balance screenings as part of their standard clinical practice. Some of these others include: Romberg Test, Dynamic Visual Acuity Test, Dynamic Gait Index, 30 Second Chair Stand Test, Tinetti Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment, the Modified Clinical Test of Sensory Integration in Balance, and the Fukuda Stepping Test. I've included the references for all of these tests in the reference list.

9. With so many options, why do you think more audiologists aren’t including this in their practice?

I think there are a few reasons as to why most audiologists do not include this as standard clinical practice, with the most likely being that we usually aren’t taught how to screen for balance disorders and fall risks in our graduate programs. Until accrediting bodies provide better guidelines to standardize vestibular education requirements, we may continue to see this lack of education continue. Even in AuD programs where vestibular education is strong, there is often still a lack of education outside of the traditional vestibular test battery.

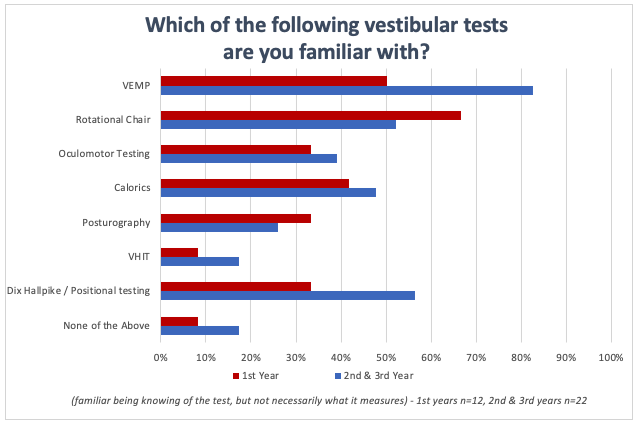

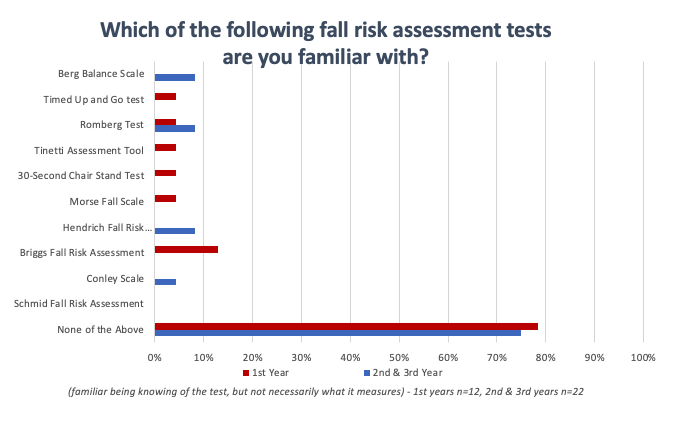

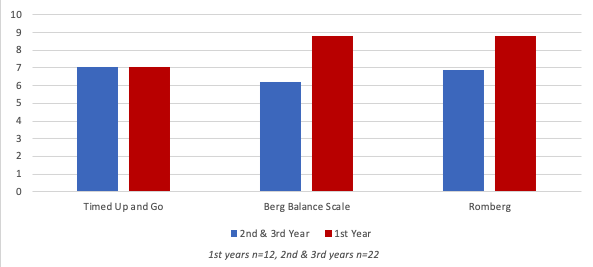

To test this theory, Dr. Michaux and I conducted a survey of AuD students from the University of Pittsburgh where we simply asked them to identify which traditional vestibular tests and which functional balance assessments they have heard of. The first-year students completed this during their first month of the AuD program and the second- and third-year students completed this prior to having a vestibular course. As you can see, most students had heard of traditional vestibular tests (Figure 1) but were not aware of the balance screening tests (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Survey results for the question, "Which of the following vestibular tests are you familiar with?"

Figure 2. Survey results for the question, "Which of the followingfall risk assessment tests are you familiar with?"

10. Which of these tests do you recommend for audiologists who want to start doing balance screenings in their clinic?

The answer to that question depends on a few factors. Time, space, and available equipment are the most important items to consider when selecting a balance screening to use clinically. \If you’re in a fast-paced clinic without much available space, a test like the Timed Up and Go Test would be a good place to start. If you find yourself with some extra time in most appointments, space isn’t an issue, and you have items such as a ruler, stopwatch, RV step stool, and a few chairs available in your clinic then a test like the Berg Balance Scale can be considered. There is also the possibility of doing several tests if you have the time and equipment. A favorite of many vestibular audiologists is the Gans Sensory Organization Performance (SOP) Test, developed at The American Institute of Balance, which combines a few different fall risk screening tests and can be used in conjunction with caloric testing to detect non-compensated vestibular weakness.

11. You mentioned using an RV step stool as part of the required equipment for the Berg Balance Scale. Why that specific?

I’m glad you asked about this. First, to be clear, RV is not a medical supply company, I’m referring to a recreation vehicle—a stool usually is needed to step inside. When we first decided to administer the Berg Balance Scale as a balance screening, our plan was to use the old plastic step stool that we had in our clinic. When we did a measurement for the exact height, we found that it was 10.5” tall! Using that step stool would not provide an appropriate functional balance assessment because most people don’t have steps with that height in their home. We decided to evaluate what is the recommended height and run (run is the horizontal tread depth) of steps. We found that 7” for the height and 11” for the tread were numbers we could include for the purposes of testing. We believed that this was an appropriately sized step based on Pennsylvania residential stair code (Pennsylvania, § 403.21). After having those measurements, we found that the metal RV step stools would give us the height, run, and the metal construction provided the durability to use this item for years to come when administering the Berg Balance Scale.

12. Is it possible that the Berg Balance Scale could replace any of your more sophisticated clinical measures?

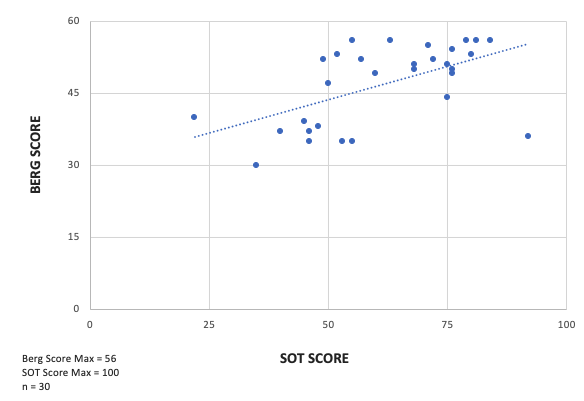

At our main facility in Pittsburgh, we are lucky to have all the equipment we need to complete comprehensive balance testing. However, over the last two years we have opened offices in 4 satellite locations that were designed to focus on audiometric evaluations and hearing aid services. We had the same question, so Dr. Michaux and I decided to investigate to see if there was any relationship between the Berg Balance Scale and computerized dynamic posturography (CDP). What we found is that there is a relationship between the Berg Balance Scale and the Sensory Organization Testing component of CDP as shown in Figure 3. However, the Berg Balance Scale can only tell you if the patient is a fall risk while CDP provides you with more specific information regarding different balance modalities, which can also be useful to other disciplines such as physical therapy. Both tests play a very important role depending on the situation, but our focus has been to find and easy way for audiologists to determine what patients passing through our clinic are at risk for falls.

Figure 3. Correlation between SOT and Berg Balance Scale.

13. That’s an interesting point. If you determine that a patient is at risk of falling, how do you proceed?

The first thing that we do is place a flag in the patient’s chart indicating that the patient has failed a balance screening and is at risk for falls. Following this, it’s important to get in touch with the patient’s other providers such as physical therapy, primary care physicians, and anyone else that can play a role in helping reduce the chances of a fall. Often the only balance measure we will complete on a patient is the screening. Working with other disciplines allows us to help the patient obtain rehabilitative services and prosthetic devices to minimize the risk of falling. Once they have these tools, we can re-administer the test to see if the patient is still at risk. It’s not surprising to us when a patient returns with an assistive device like a cane or a walker and then passes the balance screening because they’re allowed to use these devices when they complete the testing. From that point on we can continue to screen the patient as needed, but they won’t necessarily need to complete any other balance tests.

14. Not every patient who fails a balance screening needs to be referred for comprehensive balance testing?

Falls in the elderly has been a very hot topic for years. A person who falls does not necessarily have a balance impairment that we would be able to detect with a comprehensive vestibular assessment. Muscle loss, fatigue, medication effects, and other co-morbidities may all contribute to an increase in fall risk. Our role in this is to detect the risk early on so that we can do our part to make sure the patient receives the proper care to prevent these potential falls from occurring. So, the short answer is that not everyone who falls should be referred for a comprehensive vestibular assessment.

15. Are other healthcare professionals receptive when you alert them about patients being at risk for falls?

Falls are a huge concern in any medical setting. It’s a preventable incident that can have very negative long-term outcomes for a person. When other professionals see how detrimental a fall can be to a person’s health, they will take it seriously. The biggest advantage of including these balance screenings is we have the ability to designate a person of being at risk for falling. That is easy to understand, universal language that usually gets the attention of anyone seeing the flag in the patient’s chart. If you’re not part of a medical center and you have a patient that you do find is at risk for falling, it is highly recommended that you contact the patient’s primary care provider to alert them of this finding to help ensure their long-term wellbeing.

16. Should balance screening be incorporated by audiologists in the same way that we provide hearing screenings?

That is the idea that Dr. Michaux and I hope the field of audiology adopts. Many people are qualified to provide hearing screenings and we see that as a great gateway into hearing healthcare. There are many people in the healthcare professions, specifically audiologists, who have a responsibility to also provide balance screenings. At a minimum, all patients age 65 or older should complete this screening. Patients below the age of 65 should be screened if the audiologist feels that the patient may be at risk of falling or if the patient reports a history of falls.

A quick test such as the Timed Up and Go Test may provide you with the opportunity to make an immediate difference in a patient’s life. Our scope of practice covers much more than just hearing. We all should be embracing the use of balance screenings regardless of our work environment even if it adds a minute or two to the appointment time.

17. Should students also be involved in completing balance screenings?

Absolutely! It’s not uncommon to see first-year audiology and speech students go out into the community to test hearing, so why wouldn’t we encourage them to complete balance screenings as well? This test would give the students familiarity with the subject and hopefully make them more likely to continue providing balance screenings in the future.

18. Wouldn’t it be better to teach the students about this topic when they’re enrolled in a course teaching vestibular assessment?

Balance screening tests typically aren’t too complicated, and the administrator is not looking for specific vestibular impairments. That gives educators the flexibility of introducing these topics when they feel it is most appropriate. My opinion is audiology students should be taught balance screenings at the same time they are learning about hearing screenings. I don’t believe there is anything wrong with introducing this topic at the undergraduate level; and it also could be included as part of vestibular coursework.

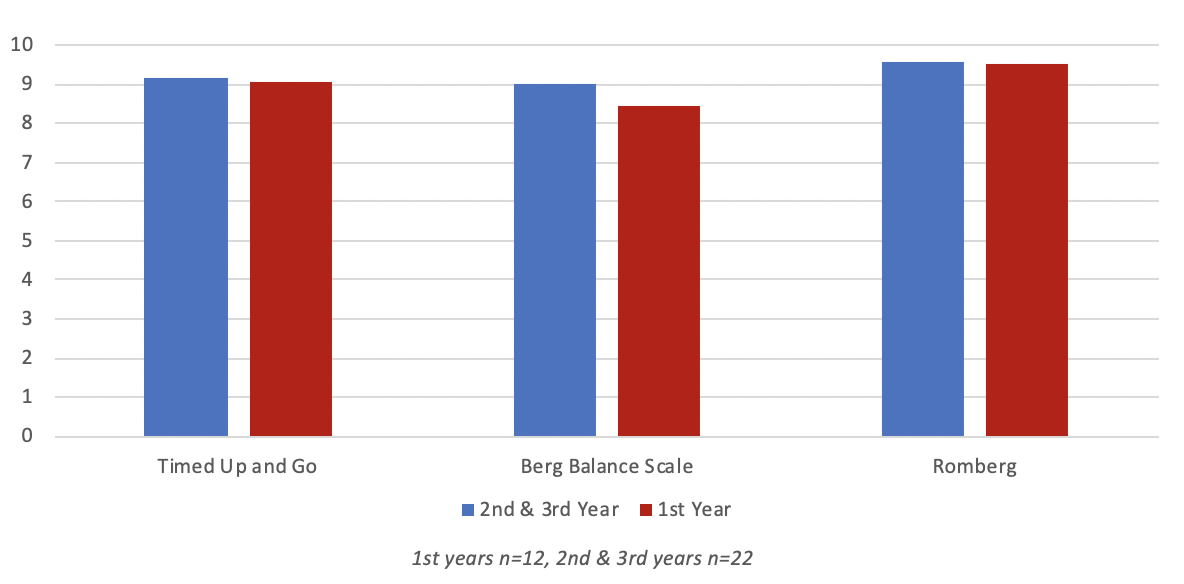

Dr. Michaux and I wanted to see how comfortable students would be in administering three different balance screenings. We asked the same group of University of Pittsburgh AuD students that we surveyed earlier to simply read the instructions of three different balance assessments and rate on a 10-point Likert scale “how comfortable they would feel in administering these tests”. After just reading the instructions, these students reported high levels of confidence in administering the test (see Figure 4). Interestingly, first-year students were somewhat more confident than the 2nd and 3rd years—we don’t really have an explanation for this.

We did the survey a few months later but this time we provided them with the written instructions and in-person demonstrations. When the students were asked how confident they feel administering the tests, nearly all the students felt fully confident in administering, scoring, and interpreting the results (see Figure 5).

Figure 4. Average Functional Balance Assessment Administration - Confidence Scale (reading directions only) .

Figure 5. Average Functional Balance Assessment Administration - Confidence Scale (reading directions + in-person demonstration).

19. Can audiologists without any experience in conducting balance screenings do this on their own?

Absolutely! The instructions for all the balance assessments mentioned in this article are clear and easy to follow. If you’re unsure about any of tests there are free instruction videos that are easy to find with a quick search on the internet. The easiest way to get over any fears about doing these tests is to find someone to serve as your practice patient and try to administer it. The more you practice the testing, the more comfortable you will be when it comes to completing the screenings on an actual patient.

20. You’ve sold me! What’s the best way for me to prepare to do balance screenings in my clinic?

The first step is evaluating your clinic schedule and patient population to determine which test will meet the needs of your clinic. Once you have identified the appropriate test, make sure you that you have the space and equipment required to administer the test. Like I mentioned, an important step is to practice so that you can feel comfortable administering the test on your patient. Next, you will need to decide what patients will receive the screening. I would recommend doing some form of screening on any patient that you feel is at risk for falling. You can determine that through a case history or simply by observing them walk during your interactions during your appointments. The final and possibly most important step is to teach your colleagues and students about these tests so that they too can become involved in making balance and fall risk screening a part of your standard clinical protocol.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Cara Michaux for her contributions to this article.

References

AIB Balance Performance Foam (includes Gans Sensory Organization Performance Test): American Institute of Balance, Largo, FL. (n.d.). Available from www.dizzy.com

Barry, E., Galvin, R., Keogh, C., Horgan, F., & Fahey, T. (2014). Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 14, 1-14.

Berg, K.O., Wood-Dauphinee, S.L., Williams, J.I., & Maki, B. (1992). Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 83(S2), S7-11.

Cohen, H., Blatchly, C.A., Gombash, L.L. (1993). A study of the clinical test of sensory interaction and balance. Phys Ther, 73(6), 346-51.

Fukuda, T. (1959). The stepping test. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockholm) 50, 95–108.

Herdman, S.J., Tusa, R.J., Blatt, P., Suzuki, A., Venuto, P.J., & Roberts, D. (1998). Computerized dynamic visual acuity test in the assessment of vestibular deficits. The American Journal of Otology, 19(6), 790-6.

Jacobson, G.P., & Newman, C.W. (1990). The development of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 116(4), 424-427.

Jones, C.J., Rikli, R.E., Beam, W.C. (1999). A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport, 70, 113–119. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028

Khasnis, A., & Gokula, R.M. (2003). Romberg's test. J Postgrad Med, 49, 169.

Morse, J.M., Morse, R.M., & Tylko, S.J. (1989). Development of a scale to identify the fall-prone patient. Canadian Journal of Aging, 8(4), 366-377.

Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry. § 403.21. Uniform Construction Code. Available from www.ncsl.org

Podsiadlo, D., & Richardson, S. (1991). The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 39(2), 142-148.

Shumway-Cook, A., Brauer, S., & Woollacott, M. (2000). Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the timed up & go test. Physical Therapy, 80, 896-903.

Shumway-Cook, A., & Woollacott, M. (1995) Motor control: Theory and applications. Baltimore, MD: Wilkins & Wilkins.

Tinetti, M.E. (1986). Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc, 34(2), 119-26. PMID: 3944402 DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb05480.x

Citation

Jedlicka, D. (2020). 20Q: Why all audiologists should be administering balance screenings. AudiologyOnline, Article 26952. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com