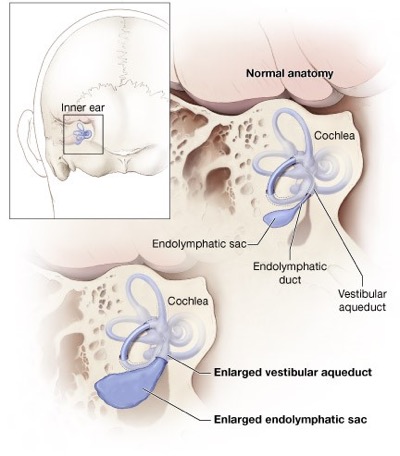

October 10, 2017 - Bigger is not always better, especially when it comes to structures in the inner ear. Enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct (EVA) has long been associated with hearing loss. A new study using a mouse model finally reveals the root cause of how this structure becomes enlarged, and could lead to new approaches to preventing and treating hearing loss associated with EVA and similar disorders. The discovery is the result of a research collaboration between Kansas State University and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), part of the National Institutes of Health. The NIDCD and the NIH’s National Center for Research Resources (now known as the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences) funded the study.

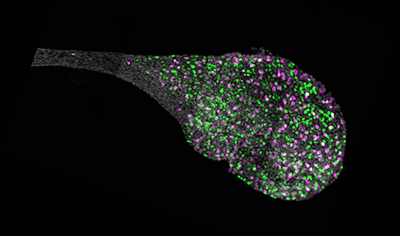

Endolymphatic sac from the inner ear of a mouse. Source: NIH/NIDCD.

The paper, “Molecular architecture underlying fluid absorption by the developing inner ear(link is external),” was published online October 10 in the journal eLife. “This study provides the first comprehensive picture of the genes and cells involved in fluid absorption by the developing inner ear,” said Andrew J. Griffith, M.D., Ph.D., senior author and chief of the Molecular Biology and Genetics Section in the NIDCD Division of Intramural Research. “We know this process is important because mutations in genes that are critical for this process cause hearing loss associated with EVA.”

About two to three out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born with a detectable level of hearing loss in one or both ears. Between 5 and 15 percent of children with sensorineural hearing loss (hearing loss caused by damage to sensory cells inside the cochlea) have EVA.

This diagram shows the anatomy of the inner ear. Hearing loss and deafness may occur when the inner ear is enlarged due to failure of fluid absorption in the endolymphatic sac. This failure of fluid absorption has now been established as a root cause of hearing loss. Source: NIH/NIDCD

Techniques developed at Kansas State University enabled the researchers to demonstrate for the first time how fluid is absorbed in the inner ear. “The purpose of this study was to gain insight into the functional, molecular, and cellular architecture of the endolymphatic sac and to identify the components of the physiologic-developmental pathway that is disrupted in EVA,” explained Philine Wangemann, Ph.D., University Distinguished Professor at Kansas State University and a co-corresponding author. “We showed that the endolymphatic sac absorbs fluid that is dependent on the gene, SLC26A4.”

A combination of three major approaches was used to define the mechanism underlying fluid absorption in the endolymphatic sac: 1) a pharmacological approach using drugs to probe for the contribution of specific ion transporters to fluid absorption; 2) a tissue-based approach surveying the transcriptome of the entire endolymphatic sac; and 3) a novel cell-based approach surveying the transcriptome of individual cells isolated from the endolymphatic sac, which became possible through techniques developed at the NIDCD.

The current paper in eLife is the sixth in a series of studies on mouse models published by Griffith and Wangemann and their collaborators. The previous studies defined when and where the SLC26A4 gene is required for normal hearing and development of the inner ear. In 2013, the researchers reported that they partially restored hearing and balance in affected mice by expressing the SLC26A4 gene. The new study provides a better understanding of the interconnection of these factors.

This study was supported by the NIH’s NIDCD (Z01-DC000060, Z01-DC000059, Z01-DC000086, Z01-DC000088, R01-DC012151, P20-RR017686).

Source: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/news