With antiretroviral drug therapies allowing people who are HIV positive (HIV+) to live longer, doctors have begun to notice that some are reporting hearing problems and have a high rate of abnormal hearing tests. The reasons for the association between HIV infection and hearing loss are unclear, as well as whether the problems are in the ear, the brain, or some combination of both.

"Is it due to the antiretroviral drug therapy used to treat HIV?" asks NIDCD grantee Jay Buckey, M.D., a professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School. "Is it due to HIV itself or complicating infections and their treatment, like tuberculosis? We just don't know."

Jay Buckey, M.D.

Credit: Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center

This is why Dr. Buckey and a team of researchers are in their second year of a five-year study working with a group of patients in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to try to understand what could be causing this kind of hearing loss and where in the hearing system the problems are developing. The study uses a portable auditory testing device developed by the research team that was originally designed for use on the International Space Station.

This study is part of an ongoing research collaboration funded by the NIH between Dartmouth Medical School and Dar es Salaam's Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) known as the DarDar program. Thanks to the growth of the DarDar program over the past decade, Dr. Buckey and his colleagues have access to clinical facilities, health providers, and a large group of HIV+ adults who are interested in and committed to participating in the research. The DarDar Pediatric Program (DPP) clinic treats HIV+ children, who also participate in the study.

The first part of the project is a cross-sectional study that is following both adults and children with and without HIV and tuberculosis—some of them receiving antiretroviral therapy and some of them not. At the clinic, participants give their medical history, watch and interact with a video questionnaire that helps them assess their hearing, and then complete a battery of auditory tests. From that point on, they are followed at six-month intervals with continued testing and medical management. Patients whose testing shows significant hearing loss are fitted with hearing aids that use solar-charged batteries, which removes a major obstacle to hearing aid use in remote locations where batteries can be expensive and hard to find.

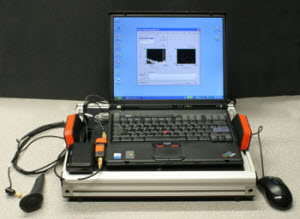

The DarDar auditory testing device is a battery-powered laptop fitted with an ear probe, a tympanometer, and a

device to measure auditory brainstem response. Credit: Creare, Inc.

The auditory testing is done using a battery-powered, laptop-based device that Dartmouth and Creare, Inc. (an engineering research and development firm in Hanover, N.H.) originally developed in collaboration with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) for use on the International Space Station. "It turned out that some of the astronauts coming back from missions were reporting hearing loss," says Dr. Buckey, "but the origins weren't clear." Because the noise in the space shuttle cabin wasn't any louder than the noise in the average airplane cabin—60 to 70 decibels—it was hard to attribute it to noise-induced hearing loss.

With NASA funding, the Dartmouth-Creare team developed the portable hearing-testing device so that it didn't take up a lot of room and the astronauts could administer it themselves while on the shuttle. The plan was to have the astronauts tested before they flew, while they were in space, the day they returned to earth, and several times afterwards. When NASA reorganized, the project was cancelled and the device never launched. Dr. Buckey, on the other hand, has flown in space. He was a payload specialist astronaut on the space shuttle Columbia in 1998 during the Neurolab STS-90 mission, which was partly funded by the NIDCD.

NASA's loss was the NIDCD's gain. Not only was the testing device well-suited for space travel, it was also useful for testing hearing in remote locations or places that had limited resources. Dr. Buckey had a conversation with the researcher at Dartmouth who had started the DarDar program, Dr. Ford von Reyn, and they realized they could combine their resources and begin to tease out the factors that could be causing hearing loss in HIV+ adults and children.

Dr. Buckey's hearing study with DarDar is continuing to enroll patients and conduct the necessary testing. Dr. Ndeserua Moshi, a Tanzanian otolaryngologist from MUHAS, is the on-site principal investigator, and Dr. Issac Maro, a Tanzanian doctor with a degree in public health from Dartmouth, manages the project on-site in Dar es Salaam. A team of people has been trained to run the hearing testing, video questionnaires, and other data-gathering activities. At the end of the project, Dr. Buckey is hoping that, beyond having comprehensive data on hearing loss among HIV+ children and adults as well as information about the prevalence, incidence, and nature of hearing loss in the population, they'll be able to sort out some of the associations that exist between hearing loss, antiretroviral therapy, and tuberculosis treatment. Knowing that, it might be possible to develop guidelines for interventions that could prevent hearing loss in the treatment of HIV/AIDS.

Taken from www.nidcd.nih.gov/news/releases/11/Pages/102711.aspx

Out-of-this-World Technology and a Down-to-Earth Infectious Disease Clinic Helps NIDCD Researchers Explore Hearing Loss in HIV-Positive Patients

Share: