During the last century, many patients have undergone a variety of brain surgeries in an attempt to alleviate all sorts of psychiatric maladies, from hysteria and depression (mainly in women) to schizophrenia and epilepsy. Early on, doctors believed that psychiatric patients suffered from aberrant wiring among different brain areas and that cutting the connections between these areas would help patients regain normal brain circuits as well as their mental health. For instance, since the 1940s, several patients with intractable epilepsy have been treated with callosotomy, a surgical procedure that severs part or most of the corpus callosum. Curiously, some individuals are already born without the corpus callosum, a condition known as callosal dysgenesis (CD).

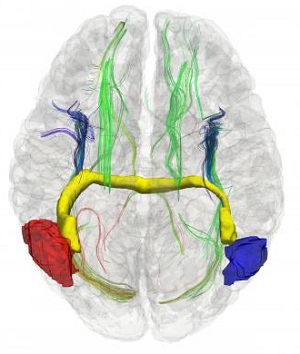

This is a 3D image showing some of the aberrant interhemispheric bundles in a "glass brain" of a subject born without the corpus callosum. In yellow, the aberrant midbrain bundle that connects the right (in blue) and left (in red) brain hemispheres. Image courtesy of Ivanei Bramati (D'Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR), Rio de Janeiro 22281-032, Brazil).

In 1968, the neurobiologist Roger Sperry confirmed that both callosotomized and CD patients have either absent or massively diminished connections between brain hemispheres. However, these two types of patients show a paradoxical difference concerning the transfer of information between the two sides of their brains. While typical callosotomized patients suffer from a disconnection syndrome in which there is minor or no communication between the left and right brain hemispheres, in CD patients, the two hemispheres are in fact able to communicate with each other.

For instance, when an unseen object is held in the right hand and thus recognized by the left hemisphere, both callosotomized and CD individuals can easily name that object verbally, because it is the left hemisphere that most often dominates verbal language. However, when an object is held in the left hand and thus recognized by the right hemisphere, callosotomized patients fail to verbally name the object because the missing corpus callosum prevents the right hemisphere from communicating with the left hemisphere. Conversely, CD patients have no difficulties in naming an unseen object regardless of the hand holding it.

The observation that the corpus callosum is the main connector between brain hemispheres earned Roger Sperry the Nobel Prize in 1981, but his own paradoxical discovery that CD patients do not present the classical disconnection syndrome observed in callosotomized patients remained unexplained until now.

In an article entitled "Structural and functional brain rewiring clarifies preserved inter-hemisphere transfer in humans born without the corpus callosum" and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a group of scientists from Rio de Janeiro and Oxford puts an end to Sperry's paradox.

Previous work had led to the hypothesis that a defect in callosal formation would cause the brains of CD patients to create alternative pathways early on in life, but little was known about these potential pathways. The group led by Fernanda Tovar-Moll and Roberto Lent at the D'Or Institute for Research and Education and the Institute of Biomedical Sciences in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, tested the brains of patients with CD using state of the art functional neuroimaging methods. The researchers were able to identify, morphologically describe and establish the function of two alternative pathways that help compensate for the lack of the corpus callosum. These pathways enable the transfer of complex tactile information between hemispheres, an ability missing in surgically callosotomized patients. Furthermore, by comparing six CD patients with 12 normal individuals, the group was able to demonstrate that CD patients present tactile recognition abilities similar to those observed in controls, indicating a functional role for these newly discovered brain pathways.

The authors believe that the development of alternative pathways results from the brain's ability for long-distance plasticity and occurs in the utero during embryo development, which indicates that connections formed in the human brain early in development can be greatly modified, and most likely by environmental or genetic factors.

These findings will change the way we perceive the mechanisms of brain plasticity and may pave the way for a better understanding of a number of human disorders resulting from abnormal neuronal connections during embryonic development.

The study was supported by different grants and fellowships provided by the Brazilian Council for Development of Science and Technology (CNPq); the CAPES Foundation of the Brazilian Ministry of Education; The Rio de Janeiro Foundation for the Support of Research (FAPERJ); The National Institute of Translational Neuroscience, Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation; and D'Or Hospital Network.

Source: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2014-05/pcc-apl050814.php