Question

When discussing evidence based practices for hearing aid fitting, what is meant by the term 'levels of evidence'?Answer

It really comes down to your ability to systematically evaluate the strength of the evidence your are reviewing. This is a fairly complicated question, and I will try and give you some practical insights that might be useful. An excellent resource to begin learning about evidence based practice is the July/August 2005 special issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. The special issue features guest editor Robyn Cox, whose article, Evidence-Based Practice in Provision of Amplification, describes a level of evidence hierarchy. This hierarchy helps us size up the strength of the clinical evidence in a systematic manner.

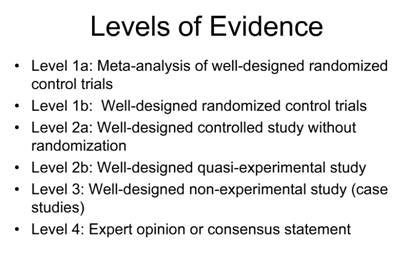

Cox's article describes 6 levels of evidence. I have included a chart below that has these 6 levels in order from the highest level of evidence (1a) to the lowest level of evidence (Level 4). The numbering here will differ slightly from Cox (2005) since I have used 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b where she uses 1,2,3,4 respectively, for the first 4 levels.

When audiologists begin integrating evidence based thinking into their clinical decision making process, they need to systematically look for the highest level of evidence in order to provide the best patient outcomes. In terms of hearing aid fitting, that usually means looking to peer reviewed journals, and research designs where the variables are controlled and randomized. The highest levels of evidence comes from studies using randomized control trials. In simple terms this means that study participants are placed into two groups, using a specific randomization method. One group receives a specific treatment (uses a certain advanced hearing aid feature, for example) while for the other group, treatment is withheld.

In hearing aid research, for various reasons, it's not often that we get above a Level 2 level of evidence. That doesn't mean Level 2 or lower evidence is bad, it just means that it's not quite as strong as Level 1 evidence. It's really up to the critical thinking audiologist to carefully evaluate each relevant study as it pertains to the clinical question we are asking.

Let's look at the other end of the evidence-based spectrum. Level 4 (Cox's Level 6) is expert opinion. Expert opinion, or a consensus statement can be, for example, a group of audiologists who make a well thought out consensus statement about a certain procedure or product. While Level 4 evidence can provide some guidance, we want to aspire to a higher level of evidence when making clinical decisions.

Level 3 evidence is a well designed non-experimental study, or a case study. For example, if you fit 4 or 5 patients with a certain hearing aid or test a certain feature, and then report your results and publish them in a non-peer reviewed journal, this would be considered Level 3 (Cox's Level 5) evidence. Again, Level 3 can provide us with some guidance, but it's still considered a relatively low level of evidence. Finally, we have Level 2 evidence, which is research from well-designed non-randomized studies. Much of the most relevant hearing aid research falls into Level 2. Non-randomized studies typically involve a group of carefully chosen participants and follow a carefully chosen study design.

Additionally, there are a couple other critical aspects of evaluating research that warrant mention. Regardless of the level, knowing if either the subject and/or researcher is blinded to the study is important to know. Also having some basic knowledge of research design and statistical analysis is important when you are trying to grade the level of evidence you have gathered to answer any clinical question. I recommend Greenhalgh (2006) as a resource, specifically chapter 5, entitled Statistics for the non-Statistician.

Applying evidence-based principles is an essential component of daily practice. When evidence-based thinking is combined with sound clinical judgement, intuition and experience, professionals are able to make better decisions that will result in improved patient outcomes.

References

Cox, R. (2005). Evidence-Based Practice in Provision of Amplification. JAAA 16(7):419-435.

Greenhalgh, Tricia (2006). How to read a paper: The basics of evidence-based medicine. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Brian Taylor, Au.D, is currently the Professional Development Manager for Unitron Hearing in Plymouth, MN. He is also an Associate Editor for AudiologyOnline. Dr. Taylor has 17 years of clinical management and teaching experience in the field of Audiology.

More information on evidence based practices can be found in Dr. Taylor's recorded course, The Essential Building Blocks of Hearing Aid Outcomes: Applying Evidence-Based Thinking, and in his text course, The Essential Building Blocks of Hearing Aid Selection and Fitting: A Beginner's Guide to Applying Evidence-Based Thinking.