Question

I often note that when I am conducting speech-mapping verification, and I have a good fit to NAL-NL2 target for the 65-dB input signal, the aided Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) is only around .70 - shouldn’t it be much higher?

Answer

For an adult with acquired hearing loss, for a 65-dB SPL input, the short answer is “no,” and here is why. There has been some research by Earl Johnson and Harvey Dillon (2011) relating the SII to prescriptive fittings. They took five different audiograms (flat, upward sloping and three different downward sloping audiograms), and looked at the SII when there was a perfect fit target for four different prescriptive methods. I'm going to focus on their results with the NAL-NL2 and the DSL. Except for the upward sloping audiogram, there was essentially no difference between the SIIs with the DSL versus NAL-NL2. With a perfect fit to target, the SIIs with the NAL-NL2 and DSL ranged from .67 to .75 for average speech. The average SII for average speech for the DSL was .70 and for NAL-NL2 was .69. You might ask, "If I hit all my targets, why shouldn't I get an SII at .8 or .9?" There's a reason why .7 is okay.

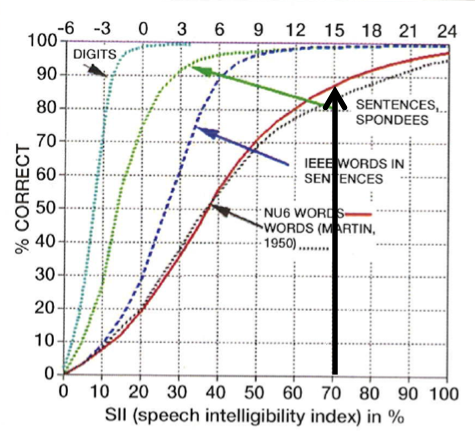

Figure 1. The relationship between the SII and speech recognition for different speech materials.

Figure 1 directly relates SII to speech intelligibility. The red line in the figure refers to words in isolation, which is the most difficult of these intelligibility tasks. At an SII = 0.7, the percent correct is about 90%. For words in sentences (dotted dark blue line) and sentences (dotted green line), it's 100% correct. These data show that an SII of 0.7 really is good enough. Again, keep in mind that you have to keep hearing aid gain and output at comfortable levels; if you simply turn up gain just for the sake of observing a higher SII, the patient may simply turn it back down or may reject using the hearing aids altogether.

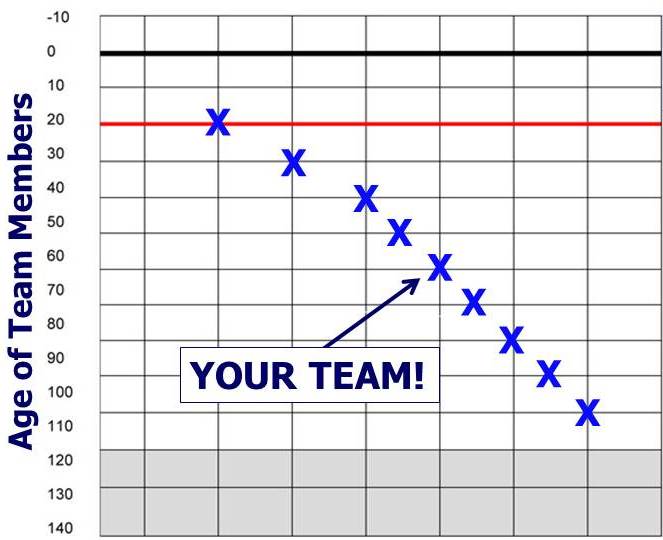

As I mentioned, one reason that you do not add more gain to achieve a larger SII, is that you have a maintain acceptable loudness, and this loudness must be effectively utilized across frequencies. I'll share an analogy, stolen in part from Harvey Dillon, to help you understand the concept of preferred loudness and effective audibility. Imagine you are the coach of a basketball team and your team has nine players of varying ages. Your players consist of a 20-year-old, a 30-year-old, a 40-year-old, a 50-year-old, 60-year-old, 70-year-old, 80-year-old, 90-year-old, and one player who is 100-years-old. These ages are an analogy for thresholds as shown in Figure 2. You're playing against a team that has all 20-year-old players. As a coach, you use the five youngest players for your starting five. Even with your five youngest players, you have a 60-year-old in the game. I hope you see the similarity to a downward sloping hearing loss, where you have areas of better hearing and areas of poorer hearing. At halftime, amazingly your team is only 12 points behind. Not too bad, but your starting five are exhausted. And, the other team has just scored 10 points and has been substituting regularly so their players are fresh. You've had your starting five in the whole first half. What are you going to do in the second half? The youngest player sitting on your bench is 70-years-old. Are you going to substitute all of your players and put in your 80-year-old, your 90-year-old or your 100-year-old? Or, are you better off to keep playing your five youngest players even if they're tired? This is exactly the point of adding in more high frequency gain when you have a downward sloping hearing loss. If you add a lot of gain to try and reach one of those high frequency thresholds (like adding in one of those old players), you're going to have to take something out because relative to hearing aids, the patient is going to turn down gain - which is the equivalent to taking out a 40-year-old player. So, adding in more high frequency gain is like putting in an 80-year-old and taking out a 40-year-old. That doesn't make good basketball sense. The NAL people have extensively researched this over the past 40 years to develop sound, accurate prescriptive targets.

Figure 2. Basketball analogy to illustrate the concept of effective audibility. Hearing thresholds are compared to the ages of players on a basketball team.

So, as I mentioned earlier, for both the NAL-NL2 and the DSLv5, an aided SII of around .70 for average speech inputs usually is okay. Now, you might ask what comes first - fitting to target or obtaining the desired SII? It’s important not to simply attempt to achieve an SII of around .70. You can craft a strange looking REAR to get to .70, but it may not maximize intelligibility; the shape of the output curves are very important. If you obtain a good match to targets for a 65 dB SPL input, you will probably end up with an SII of around .70. However, don't try and hit an SII of .70 by any means necessary and then assume you have a good fitting. As an analogy, 175 pounds is an acceptable weight for a male who is 6 feet tall. But two different males of that exact height and weight could have very different looking body shapes, including one that is not very attractive.

For more information on speech mapping, view the CE course, Signia Expert Series: Hearing Aid Speech Mapping Verification - Some Explanations for Puzzling Outcomes, available in both recorded webinar and text course formats.

References

Johnson, E.E., & Dillon, H. (2011). A comparison of gain for adults from generic hearing aid prescriptive methods: Impacts on predicted loudness, frequency bandwidth, and speech intelligibility. JAAA, 22(7), 441-59. doi: 10.3766/jaa.22.7.5