Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials.

Learner Outcomes

Jolie Fainberg: The learner objectives for today’s training are that participants will be able to identify three types of Usher syndrome. The participants will be able to describe the clinical features of Usher syndrome, and they will be able to list the treatment and intervention options for children with Usher syndrome.

Introduction

Today’s course is the first in a virtual training series hosted by Advanced Bionics. Our topic is identification and management of children with Usher syndrome. I became interested in Usher syndrome recently as several of my cochlear implant patients were diagnosed as pre-teens and teenagers ith Usher syndrome. Several of their parents became very involved in Usher syndrome research and establishing foundations. In my training as an audiologist, there was not much said about Usher syndrome, and when I queried other audiology friends, there was not a lot of information out there. Hopefully I can give you some information that will be helpful.

Usher Syndrome

Usher syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that is the leading genetic cause of deaf-blindness. It was named after Scottish ophthalmologist Charles Usher. He recognized it as a syndrome when he surveyed 69 deaf individuals who also suffered from visual impairment. Dr. Usher described the pathology and the transmission of the syndrome in a paper. He recognized the syndrome as an inherited disease. His work was a continuation of research by Albrecht von Graefe and Richard Liebreich in the late 1850s.

Although Usher syndrome is rare, with an incidence rate worldwide of about 1 in 6,000 to 20,000, it is devastating for those who are affected by it. About 10% to 12% of all children born with congenital profound hearing loss have Usher syndrome, and about 50% of all people who are deaf/blind have Usher syndrome.

Genetic Features

Usher syndrome is an autosomal recessive gene, and it manifests itself in three clinical types. Recessive means that a person must inherit the same gene from each parent in order to have the disorder. A carrier is a person who has only one affected gene, but does not have the disorder. They can pass it on, either as an affected or unaffected gene to their children. An individual with Usher syndrome usually has inherited the gene from each parent.

When you have two parents, each of which have an affected gene, they have a one in four chance (25%) of having a child with Usher syndrome, a two in four (50%) chance of having a child who is a carrier, and a one in four (25%) chance of having a child who neither has Usher syndrome nor is a carrier.

We find that parents usually have normal hearing and vision and do not know that they are carriers of the Usher syndrome gene. Right now, from family history and genetic evaluations, we do not always have the ability to identify the gene in a person. The National Institute of Deafness is working with other organizations to try to find more of the genetic disorders so they can identify this much sooner.

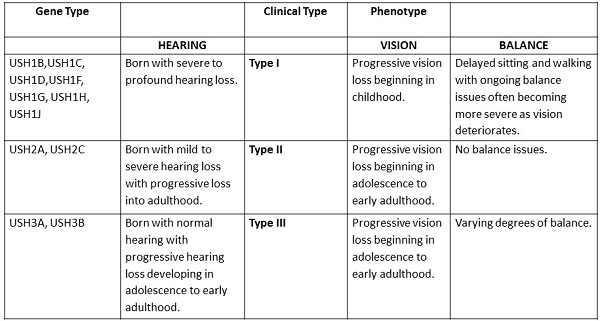

There are three clinical types of Usher syndrome. Type I is characterized by a severe to profound deafness at birth, delayed development in motor skills, vestibular problems, and early onset of vision loss due to retinitis pigmentosa. There are seven distinct subtypes from IA to IG. Usher syndrome type I is estimated to occur in about 4 in 100,000 people. It seems to be more common in certain ethnic populations such as Ashkenazi Jews and the Acadian population in Louisiana. Ashkenazi is Jewish people who come from central or Eastern Europe.

Type II is characterized by mild to severe hearing loss at birth, no balance issues, and some evidence of sight loss in the teen years as a retinitis pigmentosa. Type II has three described subtypes, IIA, IIB, and IIC. Type II is thought to be the most common form of Usher syndrome. Type III includes progressive hearing loss, possible vestibular issues, and progressive vision loss. Type III Usher syndrome is rare and more common in the Finnish population.

Figure 1 is a summary of the types and clinical manifestations.

Figure 1. Types of Usher syndrome and the hearing, vision and vestibular manifestations.

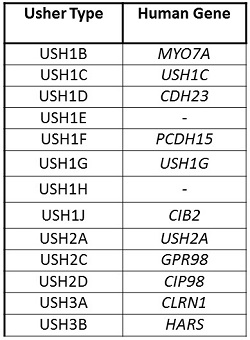

There are currently 11 genes associated with Usher syndrome. Each of these known genes and possibly others that have yet been recognized synthesize proteins that play a role in the formation and health of the sensory system of the eye, ear, and vestibular systems. Figure 2 shows the human genes which are associated with each type of Usher syndrome.

Figure 2. Usher type and the associated human gene.

Diagnosis

I am going to talk a little about the diagnosis of Usher syndrome. As I mentioned before, parents usually do not know that they are carriers. Genetic testing for Usher syndrome is not widely conducted. If a child is known to have a hearing loss, when they go for genetic testing, they are often not screened for Usher syndrome.

The diagnosis for vision is a complete evaluation of the eye including their peripheral vision, as this is where retinitis pigmentosa first shows up, an electroretinogram to measure the electrical responses of the eye’s light sensitive cells, and a complete retinal examination, looking at the retina and other structures in the back of the eye. The ERG (electroretinography) is a test that cannot be conducted on very young children.

For hearing, a completed audiological evaluation should be completed including audiogram, auditory brainstem response (ABR), impedance measures, and otoacoustic emissions. A complete vestibular evaluation including electronystagmogram (ENG) which measures the voluntary eye movements that signify a balance problem.

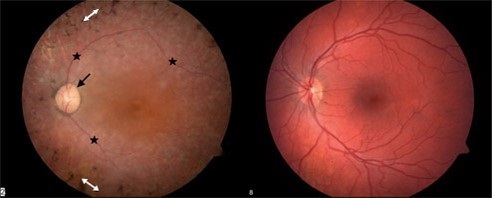

The gradual loss of vision in people with Usher syndrome is caused by retinitis pigmentosa, or RP, which affects the layer of light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye. RP is caused by a mutated gene in the retina which does not produce a protein needed by the rods to survive. In early adolescence, Usher syndrome patients begin to lose their night vision because of the destruction of the rods. As the rods die out, peripheral vision begins to narrow leading to tunnel vision. The central vision, which is controlled by the cones is eventually affected leading to complete blindness.

With Type I Usher’s, night blindness is typically apparent by age 10. These children are often described as clumsy, bumping into things, or tripping over objects. Significant deterioration of the visual field and acuity begins in the second or third decade of life, with cataracts being a common complication. Several of my patients are showing deterioration of their visual field at a much younger age than in their 20’s. Several of them in their mid-teens have significant retinitis pigmentosa and are not able to drive or do other things that require full visual field.

The regression of RP can occur at different rates in different individuals, but many people with Usher syndrome are legally blind by early adulthood. Many people with RP retain some central vision throughout their lives, however.

The following image (Figure 3) shows a healthy retina on the right and one with Usher syndrome on the left. The optic nerve is very pale. The vessels are very thin, and there is a characteristic pigment called bone spicules.

Figure 3. Comparison of healthy retina (right) and retina affected by Usher syndrome (left).

Research scientists are working to determine ways to slow, stop or even reverse the degeneration of the rods and cones, or possibly bypass the rods and cones to maintain vision via retinal implant. There has been some recent news about an eye implant. They are doing a lot of research to see if there is a way, like a cochlear implant, that they can implant a device to help with vision.

They are also looking at gene replacement therapies, gene preservation therapies, and drug therapies. The cutting edge research is trying to look for safe treatments that are closer to restoring hearing as well as sight to individuals with Usher syndrome. They are looking for ways in which they can allow these patients to see. Cochlear implants are being used quite often. The surgeon I work with said that one of the reasons why a visual implant has been more difficult is because the eye is a much more difficult structure to replicate than the ear.

Hearing loss. In Type I Usher syndrome, most patients have congenital, profound sensorineural hearing loss at birth. Because the visual impairment is usually discovered later, the family may experience a second period of grief upon learning that their deaf child will eventually be blind. These children benefit from early bilateral implantation and auditory verbal therapy.

Type II Usher syndrome exhibits as stable, sloping, moderate to severe sensorineural hearing loss and most of these patients can benefit from amplification. The subtype IIA, however, may demonstrate progressive hearing loss not found in the other Type II expressions. These children may eventually need a cochlear implant as their hearing loss progresses.

In Type III Usher syndrome, hearing loss is not present at birth, but can be progressive over time. In the first decade of life, the hearing loss is a moderate sloping to profound and progresses to profound by the fourth decade. We do not typically see Usher Type III here in the United States.

Vestibular function. Vestibular dysfunction was something I did not know about when I first began to look at Usher syndrome. There is a prevalence of vestibular dysfunction in these patients. Type I Usher syndrome is commonly associated with absent vestibular function, and approximately 50% of Usher Type III patients will develop vestibular dysfunction. The presence of vestibular dysfunction in a child with profound hearing loss would suggest Type I. In fact, 36% of those born with profound hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction have Usher syndrome Type I. As other causes of profound hearing loss with vestibular issues are ruled out, the likelihood rises that the child has Usher syndrome.

One of the first manifestations we can see in these patients as early as infancy that points to Usher syndrome is head lag. By age six weeks, babies with normal vestibular function can hold their heads in line with their bodies when pulled to a sitting position. The heads of babies with Usher syndrome Type I hang backwards. When you pull up babies with normal vestibular function, they can keep their head up.

In addition, when held upright, these babies cannot steady their heads, which can result in uncontrolled bobbing, or their heads fall to the side when placed in a sitting position as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Vestibular dysfunction causing an infant’s head to fall to the side.

In addition, they often arch their backs when held. They are late to sit at nine to 12 months of age rather than seven months of age. Tripod sitting is also common. Once they do start sitting, W-sitting is common. They are late to crawl and they usually start with a combat crawl.

Most of these children do not walk early. They walk at 18 months of age or later. Several of my patients did not walk until they were 2.5 years old. They typically have poor balance or an awkward gait, which remains obvious through their preschool years.

In preschool and early childhood, these children are often awkward, uncoordinated, and clumsy in playground games. They may fall often and easily. They bump into furniture and lose their balance when pushed slightly off of their center of gravity.

In later childhood and through adulthood, we find that there are some cognitive dysfunctions as well. They have a decreased ability to track two processes at once. They have difficulty in handling sequences and decreased mental stamina. Their memory retrieval is decreased. They have a decreased sense of internal certainty; they do not feel as comfortable in their surroundings, and have a decreased ability to grasp a large whole concept.

Treatment and Intervention

Currently, there is no cure for Usher syndrome. The best treatment involves early identification and intervention. The exact nature of the intervention will depend on the severity of the hearing and vision loss.

In Usher Type II and III, amplification is recommended as soon as the hearing loss is identified. In addition, speech-language or auditory-verbal therapy should be started as soon as the child receives hearing aids. Most of these children will do well with early intervention. Because the hearing loss can sometimes be progressive, it is very important that these children are monitored closely receive audiological evaluations. If and when their hearing does decrease and they become in the severe to profound range, they can get a cochlear implant as soon as possible.

For Type I Usher, early bilateral cochlear implantation is the most effective treatment along with intensive auditory-verbal therapy. Prior to the advent of cochlear implants, most of the patients were only able to use sign language. Cochlear implantation has changed the course of intervention, reducing the impact of hearing issues for a patient with Usher syndrome. In our clinic, we are now bilaterally implanting almost every child within the first year of age. We are trying to get these children identified and implanted with their first implant by one year of age. If we are able to see these children, even if we do not know yet that the child has Usher syndrome, having bilateral cochlear implantation and aggressive therapy will reduce the impact of hearing loss in these patients.

For individuals who have been diagnosed with Usher syndrome, connecting with an agency that can provide comprehensive vision rehabilitation services will be critical to their overall adjustment and success in learning to live with combined challenges of hearing and vision loss. A certified vision rehabilitation therapy and orientation and mobility specialist provide training in new skills and strategies for learning to live with reduced vision. They can introduce tools and technologies that will maximize independence while simultaneously providing training that demonstrates to the individual that independence in life activities is possible.

This “guided success” approach is the key to successful adjustment, and most organizations that provide this service are able to do so throughout the individual’s entire journey. In other words, as their vision and hearing changes over time, they can adjust the type of interventions for these children and their families. The vision and mobility specialists will often visit the patient in their home and work with them on guiding them around the house, figuring out how to cook, how to clean, how to manage laundering clothes, et cetera. As their vision decreases over time, they can add new skills.

Some ophthalmologists believe that a high dose of vitamin A may slow, but not halt, the progression of retinitis pigmentosa. This recommendation was based on the findings of a long-term clinical trial supported by the National Eye Institute and the Foundation for Fighting Blindness. The research recommend that most adult patients with the commons forms of RP take a daily supplement of 15,000 IU of vitamin A in palmitate form under the supervision of an ophthalmologist. However, this vitamin therapy is still controversial. Several of the patients I have with Usher syndrome started taking that vitamin A supplement as soon as they were diagnosed. I think the jury is still out as to whether this therapy will work overall.

For vestibular issues, physical and/ or occupational therapy can help if the child can be identified early. Many of my patients did not pay attention to the vestibular problems and figured it was something else. These children did not receive physical or occupational therapy. Hopefully as we understand more about Usher syndrome and the associated vestibular issues, we can start therapy on these children much sooner.

Case Study

The next thing I want to present is a case study of some of the patients that I see. We saw a set of boy/girl twins who were born at 32 weeks. They had an ABR in the hospital with a profound hearing loss for both ears. Initially, the parents wanted to know if it was something genetic. They had just the boy tested. At that time, the Connexin 26 gene was found. At that point, they never tested the daughter and assumed that she had Connexin 26 as well.

This was a very assertive family. They brought these children in when they were very young, and they received their first cochlear implants at 12 months of age. They participated in intensive auditory training. They began talking within the first six months of use of their cochlear implant. They attained excellent and listening and spoken language skills.

They received their second cochlear implant at 4.5 years of age and were mainstreamed into a private school by kindergarten age. At that time, bilateral implants were not a common recommendation, especially in infants and toddlers. The vestibular dysfunction was noted early on, but it was discounted because they were premature. The physicians who saw these children felt that some of the vestibular issues would go away because they were premature. Since they thought the etiology of the hearing loss was Connexin 26, no one ever mentioned Usher or looked into it.

At age 12, the female twin starting having difficulty with her night vision. She wore corrective lenses as well. They went to see an ophthalmologist. The mom had mentioned that they have several incidents with the young lady where she was not able to see anything around her in a dark hallway. The ophthalmologist saw yellow spots on her retina and referred them to a retinal specialist. The retinal specialist noted that there was rod dystrophy.

The parents looked that up on the Internet and found Usher syndrome, although no one had mentioned Usher syndrome to them. The daughter got ERG and genetic testing, which confirmed that both twins had Usher syndrome Type IC. The son did not manifest the vision problems as early as his sister.

The twins are now 14 years of age and are doing very well in 8th grade at an academically challenging school. For their case, early bilateral cochlear implantation decreased the impact of the hearing loss. Since writing this, I have seen these patients. I was talking with them about how they are affected by Usher syndrome at this point. For both of them, their vision has maintained fairly stable. The boy has fewer vision problems. The girl will probably not be able to drive, as her vision problems are more severe. Their other vestibular issues do not cause them too much trouble, but they are not particularly sports-oriented. At the time, they were going to be flying with their parents to Germany to visit a researcher who is doing some groundbreaking research on Usher syndrome. The family has started a foundation to pay for research for Usher syndrome.

For my patients with Usher syndrome, early implantation made a big difference. In hind sight, all of these children had vestibular issues as babies and young children. This is going to be something that we need to pay attention to. If a child has profound hearing loss and has vestibular dysfunction, if other diagnoses have been ruled out, then you need to look at Usher syndrome and potentially request a specific genetic testing for Usher syndrome. At this time, because of the cochlear implants, hearing loss is less of an issue than the vision loss.

The collaborators from New York and Israeli universities pinpointed a mutation on one of the genes (R245X), and this one accounts for Usher syndrome in Ashkenazi Jews. They recommended that Ashkenazi Jewish infants with bilateral profound hearing loss should be screened for Usher syndrome. One of my patients, who has two children with Usher children have also started a foundation for children with this mutation; that information is listed at the end of this presentation.

Scientists are working to identify and determine the function of all of the genes that cause Usher syndrome. This research will hopefully lead to improved genetic counseling and early diagnosis, and may eventually produce more treatment options.

Conclusion

Current newborn hearing screenings and follow-up audiological testing provide only the recognition of hearing loss. Although genetic testing is sometimes recommended, it is often limited to the hearing genes, therefore limiting the possible detection of the Usher gene. The age of diagnosis for hearing loss has gone down because of newborn hearing screen, but the age of diagnosis of Usher syndrome is still about 10 or 12 years of age. There is a significant gap in time where these children could potentially be getting vitamin A therapy if beneficial, as well as other interventions and therapies.

Early treatment is recommended including hearing aids, assistive listening devices, cochlear implants, orientation and mobility training, and communication services for independent living including Braille instruction, low-vision services, speech-language therapy, and auditory-verbal training. As you can see, we have a wealth of things that can be done to help these patients live an independent life.

Audiologists, otologists, auditory-verbal therapists, speech-language therapists and ophthalmologists should be aware of the characteristics associated with Usher syndrome. They can recommend testing that includes the Usher genes as well as a referral to a retinal specialist. I think audiologists will end up being some of the first people to make these recommendations because these children are first identified with hearing loss.

It is very important that we understand the vestibular issues. It is possible that with some of this new research and with the families who are doing some work, we can have the Usher syndrome gene identified in initial genetic testing. If a child goes in for initial genetic testing, looking for the Usher syndrome gene will be part of that evaluation.

I want to thank my co-contributors. Melissa Chaikof is the parent who started the Usher 1F Collaborative. Susan Trotochaud is the mother of the twins, and she has started the Usher 2020 Foundation. Nancy Parkin-Bashizi is director of Vision Rehabilitation Services of Georgia.

The following resources (Figure 5) have very good, current information about Usher syndrome.

Figure 5. Usher syndrome foundations and resources.

Questions and Answers

Is throwing back of the head a symptom of vestibular dysfunction for a child that is between six to twelve months of age?

Yes. They will arch their back, and throw their head back. That is a common symptom of vestibular dysfunction.

I currently have a four-year-old with Usher Type I. She does not qualify for in-school physical therapy at this time. Would you recommend outside physical therapy now, even though her scores did not qualify her?

It would potentially be a good idea to get a second opinion. She may not be exhibiting vestibular problems that require therapy, but certainly getting a baseline outside the school system would be a good idea. State guidelines are all different, but in our state, the guidelines for offering therapy of any sort say that the child has to be educationally handicapped. Their problem has to affect their education. If that does not apply, then they are not given therapy in the school. Sometimes these children do qualify for therapy in the community, but do not qualify for therapy in the school system. I think it would be a good idea to have her evaluated in the community.

You said that Type I Usher syndrome exhibits early onset of vision loss. How early are you usually seeing that vision loss?

Most of my patients have noticed it in their pre-teen and teenage years. The youngest that I have seen was about age 11. The children do not seem to show any vision loss before then; however, there is some research that is looking at the possibility of having children who are suspect of having Usher syndrome have a retinal evaluation very early on, as it might show some problems that do not cause vision loss at that time. Most of the time, the night blindness, which is the first manifestation, will not show up until pre-teen to teenage years.

You mentioned that you recommend closely monitoring children with Usher Type I. From an audiologic perspective, how often are you usually seeing these children?

When the children are very young, this depends on whether we are doing amplification or cochlear implants. With cochlear implant patients, we are seeing children as often as once or twice a month in the first year, depending on their needs. After that first year, I often seen those children about every three months for the next year or so, and then up to about every six months through their school years. Of course, if they have any problems, they can come in at any time.

We manage children with hearing loss a little less often that first year, probably every two to three months. We check their hearing and aid use and make new ear molds. However, if a child possibly has a progressive hearing loss, we will monitor them a little more often, at least twice a year once they are in school.

Did the twins have Connexin 26 and Usher?

Yes. I believe they did test the young woman, and she had Connexin 26 as well.

You mentioned that the twins exhibited signs of vestibular dysfunction, but people attributed that to prematurity and did not think of Usher’s at the time. Do you remember specifically what vestibular problems they were exhibiting?

They did have the head lag, where their head would bob back, and when they were put in a sitting position, their head would slip to the side. Both of them, as they were toddlers and even into the preschool years and primary school, were uncoordinated in their skills and had trouble with sports.

Why are we not seeing healthcare systems automatically testing for Usher when conducting genetic testing?

There are still not a lot of places that do the genetic screening for Usher, and maybe the incidence is not considered high enough. I am not sure why they do not offer it routinely. As I said, these parents are working and lobbying to have Usher’s as part of the regular screening process, but for some reason, they are not screening unless someone specifically asks for the Usher gene to be identified.

What has your experience been with insurance paying for the genetic testing for your children before they are diagnosed with Usher, but presenting with hearing loss and vestibular issues?

I do not know about reimbursement; I think it depends on the insurance carrier.

Do you know if adults have the same physical symptoms as infants with the neck and the back in the vestibular issues?

They do have some vestibular issues, but I do not think they have the head lag. That typically develops much earlier, and the child eventually, even though they are late sitting and walking, does gain that head and neck control. Before they can walk, they have to gain that head and neck control. The main vestibular features in adults is clumsiness, awkwardness, and bumping into things. Some of them are also dealing with night blindness as well.

You mentioned that individuals with Usher syndrome benefit from a number of different services, such as services from PT, OT and speech therapy. Do your patients have any difficulty finding those service providers who are used to and comfortable working with individuals who have both vision and hearing loss?

That is a good question. It depends on where you live. When you are in a larger metropolitan area near a children’s hospital, there is a better chance of findings people who can manage those children. Initially, those children will likely receive speech-language or auditory-verbal training. Some families will have difficulty finding someone who is used to working with a child with a cochlear implant if they live in an area that does not have a lot of people who understand that.

Much varies state by state on how good the deaf/blind services are. I have had patients who have moved to other places, and sometimes the services are better and sometimes they are worse. As audiologists, we are not given any training on deaf/blind patients, and I am not sure about physical and occupational therapists. The people most trained for this are the vision, mobility and orientation specialists. They are not necessarily providing therapy, but they are providing intervention to help the patient manage their life and become independent.

Do you know if any of your resources might have information on how to find service providers who have experience in working with individuals who have both hearing and vision loss?

I believe the national association may have that. There are conferences and seminars that happen on a regular basis, and I think they are attended by people who are interested in Usher syndrome. I am not sure if they manage a database, but they may be able to give a family a direction to go in, what questions to ask, how to look for what they need, et cetera. I do not know if they offer specific names of providers in each state.

Cite this Content as:

Fainberg, J (2015, May). Identification and management of children with Usher Syndrome. AudiologyOnline, Article 14162. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com