From the Desk of Gus Mueller

About 10 years ago, I was in the middle of a big project and I encountered some computer problems. I sensed that the problems were at least partially related to my limited understanding of computer workings, so I called my computer-guru audiologist buddy Paul Dybala for some free assistance. Paul had me go online and enter a few things, and then to my total shock, the arrow for my mouse started moving on the screen—and I wasn’t touching my mouse. After I got over the creepiness, I realized that Paul had taken over my computer. The little mouse arrow zipped around faster than I’d ever seen it move before, and he had my computer problems solved in a couple of minutes. Wow—someone sitting in Dallas was controlling a computer hundreds of miles away—pretty cool.

About 10 years ago, I was in the middle of a big project and I encountered some computer problems. I sensed that the problems were at least partially related to my limited understanding of computer workings, so I called my computer-guru audiologist buddy Paul Dybala for some free assistance. Paul had me go online and enter a few things, and then to my total shock, the arrow for my mouse started moving on the screen—and I wasn’t touching my mouse. After I got over the creepiness, I realized that Paul had taken over my computer. The little mouse arrow zipped around faster than I’d ever seen it move before, and he had my computer problems solved in a couple of minutes. Wow—someone sitting in Dallas was controlling a computer hundreds of miles away—pretty cool.

It occurred to me that that application easily could be used to remotely program hearing aids. I wasn’t the first to think of this, as I soon learned remote hearing aid programming already was happening at a couple major medical centers. That was all a decade ago, and a lot has happened since in the world of teleaudiology. Today we see routine hearing testing, advanced audiologic diagnostic measures, hearing aid verification, auditory rehabilitation and patient counseling, all delivered via teleaudiology.

Gus Mueller

Some of you may have had your first teleaudiology experience at a special session of the 2009 American Academy of Audiology meeting, when an audiologist at that session evaluated a patient in South Africa. South Africa wasn’t a random choice, as it just so happens that one of the experts in teleaudiology hails from this country. We have him with us this month at 20Q to review the current status of telehealth, and how audiology services are being implemented around the world.

De Wet Swanepoel, PhD, is a professor in Audiology at the Department of Communication Pathology, University of Pretoria, South Africa and a senior research fellow at the Ear Science Institute, Australia. He serves on a number of international committees including the executive board of the International Society of Audiology, the World Health Organization ICF Core Set for Hearing Loss, and he is co-chair for the American Academy of Audiology Taskforce on Teleaudiology.

In addition to teleaudiology, Dr. Swanepoel’s publications, research and clinical interests span the fields of early identification and diagnosis of hearing loss, and the objective measures of auditory function. As he explains in this 20Q, De Wet has been involved with research with a new audiometer used in teleaudiology, dubbed the KUDUwave, named after the antelope-like South African kudu. It is somewhat ironic that the publication of his which undoubtedly generated the most international interest was about a device traditionally made from the kudu horn—the vuvuzela. If you watched any of the 2010 FIFA World Cup from South Africa, you know about the vuvuzela, and you know it’s loud—about 120 dBA from a meter away, according to De Wet’s (and friends) much publicized report.

The horn that we are blowing this month at 20Q is about the future of teleaudiology--I’m sure you’ll enjoy De Wet’s excellent review of this emerging area.

Gus Mueller, Ph.D.

Contributing Editor

October 2013

To browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller articles, please visit www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Audiology to the People – Combining Technology and Connectivity for Services by Telehealth

De Wet Swanepoel

1. It seems that over the past few years I’ve been hearing the word “telehealth” more frequently in audiology-related discussions – why the interest?

Telehealth is a relatively new field of healthcare. In the past two decades we’ve experienced an unprecedented growth in information and communication technologies (ICTs) that is revolutionizing the way in which modern society communicates and exchanges information. These technologies are also impacting and even changing our modern health practices. In the global health care arena where the dominant challenges revolve around issues of access, equity, quality and cost-effectiveness, telehealth is demonstrating promise to provide a cost-effective and sustainable means of service provision in general health care and in audiology. I suspect that the reason you are hearing this term more is that there is a growing need for audiologic services globally and this may be addressed at least in part by employing telehealth services.

2. What populations do we usually have in mind when we think of telehealth?

Traditionally, telehealth is aimed at populations with restricted or limited access, often in remote regions. This may include rural areas like Alaska or the Australian outback but in some cases it may also be inner urban populations where services are not easily accessible. In recent years the populations for which telehealth is primarily aimed have also started to shift to general populations in an attempt to increase the efficiency of health care delivery. A good example of this are the telehealth services that are being implemented by the Veterans Affairs across the U.S. So although it’s primarily for underserved populations, it is also being considered as part of more standard practices.

3. I know that many people link telehealth to cost-savings, but doesn't it require expensive video-conferencing equipment and high speed, state-of-the-art Internet connectivity?

While you’re right that telehealth used to be associated with excessively costly equipment, advances in technology have now made it entirely possible in many cases to provide these services using free software such as Skype or ooVoo for videoconferencing and similarly for remote desktop sharing software applications. It is important to acknowledge however, that some telehealth applications, like tele-intervention, may still be facilitated best using more costly and advanced stationary video-conferencing facilities.

4. Tele-intervention? You lost me there. What’s that?

Tele-intervention refers to the provision of intervention services using telehealth means. In audiology and related disciplines this may specifically refer to provision of early intervention services to infants and young children who have hearing loss. Although not typical in the US, in many other parts of the world early intervention services for infants and children with hearing loss is provided by audiologists. If its done remotely using telehealth it is tele-intervention.

5. Okay, got it. What about developing countries where Internet connections are rare – surely this must hinder the applicability of telehealth in these regions?

Fixed line Internet connections in developing world regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa, are very rare but mobile connectivity is exploding. More than 90% of the world’s population are now living with mobile phone reception. Interestingly, lower income countries are now more mobile and own more phones than the high income developed countries. So connectivity is different in these regions – not through fixed line connections but through cellular networks. This means connectivity is reaching into the most remote and rural parts of places in sub-Saharan Africa and opening up the door for telehealth services.

6. Not to sound old fashioned, but why do we need to provide our services in new ways if it’s always worked well with patients visiting an audiologist’s office?

Are you sure it’s always worked that well? Telehealth has been promoted by agencies such as the World Health Organization to hold great potential to improve access, quality, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of health care services particularly for populations who have traditionally been underserved (WHO, 2011a). Research evidence points to improved efficiency in competitive health care environments using telehealth services as has recently been demonstrated by Dharmar and colleagues (2013). Furthermore, telehealth may bridge general barriers often created by distance, poor travel infrastructure, severe weather and unequal distribution of health care providers in urban and rural settings or even across world regions. These potential advantages of telehealth are particularly appealing when considering the growing need for audiological services globally.

7. You say, “the increasing need for audiological services” – why are our services needed more?

Hearing loss is increasing – and rapidly so around the world. This is attributed to the increase in global life expectancies, which means more persons end up with hearing loss due to ageing being the most common cause of hearing loss. Since 1990, average life expectancy has increased from 64 to 68 years of age in 2009 with an increase from 76 to 80 years of age in high-income countries (WHO, 2011b). This is resulting in an unmatched growth in hearing loss prevalence expected for the foreseeable future. In countries like the USA, baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) are now entering the geriatric age categories. Because of longer life expectancies and the disproportionately large numbers of baby boomers in relation to other birth cohorts there will be unprecedented demands for hearing health services. The growing number of persons with hearing loss globally raises the question of how they will be able to access audiological care.

8. I understand hearing loss is increasing but aren’t the numbers of trained audiologists also increasing to match this demand?

Audiologists are a scarce global health care commodity. From a global perspective close to 80% of persons with hearing loss cannot access hearing health care services because they reside in developing countries where audiologists or other hearing health care workers are unavailable (WHO, 2006; Fagan & Jacobs, 2009; Goulios & Patuzzi, 2008). In sub-Saharan Africa for example, many countries have no audiology or ENT services (Fagan & Jacobs, 2009). Of the 46 countries constituting this world region, which comprises almost 1 billion people, there is only one country, South Africa, with tertiary level education for audiologists.

This is not only a developing world problem, however. In a recent analysis, the projected growth rate of new audiology graduates in the USA demonstrate a growing mismatch between the demand for audiological services and capacity to deliver these (Windmill & Freeman, 2013). According to this study, the number of persons entering the profession will have to increase by 50% immediately and attrition rate lowered to 20% to meet the US demand (Windmill & Freeman, 2013). Alternatives, including increased capacity for service delivery through telehealth, are suggested as ways of improving the audiological service-delivery capacity by this study.

9. I’ve heard the term telemedicine, telehealth and eHealth thrown around. Which one are we talking about here, or are they all the same?

You're right, there are a lot of terms used in this field that often mean virtually the same thing. Telemedicine was originally used to encompass the provision of medical services through information and communication technologies. The term “telehealth” was introduced later to encompass a broader spectrum of health-related functions, including aspects of education and administration. More recently, the term “eHealth” has been used to include aspects related to data management and processing. Evidence, however, suggests that these terms are used interchangeably by health providers and consumers, and are ambiguous in their definition and the concepts to which they refer. As a result of the ambiguity, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Telemedicine Association (ATA) have adopted “telemedicine” and “telehealth” as interchangeable concepts (WHO, 2011a; ATA, 2013).

Another variant often used is to add the prefix “tele” before a field of health care such as tele-dermatology, tele-psychiatry and also tele-audiology. I’m often asked if telehealth is a sub-specialty of medicine. It isn’t. Rather, it is a means by which existing health care needs may be served using information and communication technology. This allows health care expertise to be linked with patients and with other health experts with the ultimate aim of providing better access, efficiency and cost-effectiveness to health care services like audiology through the two basic models of telehealth.

10. Can you briefly explain these two basic models of telehealth?

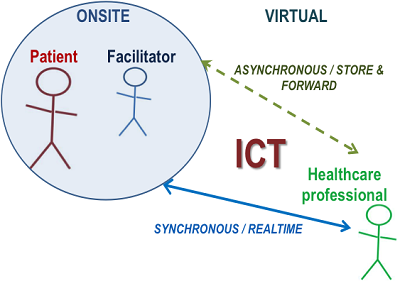

These models relate to the timing of the patient-to-health professional interaction or between health professional-to-health professional interaction (WHO, 2011a). The first model has been called “store-and-forward” or asynchronous telehealth, and involves sharing pre-recorded clinical information from one location to another. The information may be relayed from a patient site to a health care provider, or between health care providers. An example may be something as simple as sharing a pre-recorded auditory brainstem response (ABR) evaluation by email to an expert colleague for an opinion on diagnosis and management.

Figure 1. Illustration of the synchronous and asynchronous telehealth models.

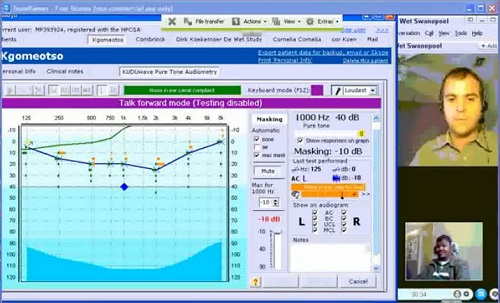

In comparison, “real time” or synchronous telehealth requires that both individuals (e.g., the health care provider and patient) are simultaneously engaging in information exchange. A typical example may be a consultation with a patient using video-conferencing, but it may also include diagnostic assessments by specialists remotely controlling a computer-operated diagnostic device connected to a patient. You’ve probably heard of hearing aids being programmed for a patient at a remote location by an audiologist at a major clinic hundreds of miles away. Both synchronous and asynchronous telehealth models require that information be shared using ICTs which can range from simple technologies including a fax machine, two-way radio or landline telephone, to more advanced technologies such as integrated shared server uploads, video-conferencing and remote desktop-sharing software (An example of a synchronous diagnostic audiometry evaluation by an audiologist in Dallas Texas on a patient in Pretoria, South Africa can be viewed here [click on image to play video]:

In practice, these two telehealth models may also be used in combination and is commonly called a “hybrid” model.

11. I can see how an asynchronous model can save time for the health care professional, but surely if the audiologist is not with the patient someone else has to be there?

You’re absolutely right. A key element required for the success of a telehealth program depends on the support personnel, in particular the telehealth facilitator. Telehealth services typically utilize non-specialist personnel referred to as telehealth facilitators, to facilitate the telehealth encounter that link the health provider and the patient. These personnel may vary in their capacity from community health care workers, assistants, and nurses. They are not there to make diagnoses or even interpretations but merely to facilitate the information exchange for the specific telehealth encounter. These facilitators must be thoroughly trained in the required equipment, procedures, protocols, and patient interactions related to the service provided. Regular monitoring and retraining is important. The quality and success of a clinical telehealth service is often just as good as its facilitator.

12. I’m thinking about my routine audiologic diagnostic procedures. Can these really be streamlined using a telehealth service?

Automation is an important part of telehealth services, especially for asynchronous models. Using automation means that procedures such as evaluations can be facilitated by onsite personnel (i.e. a telehealth facilitator) for later interpretation by an audiologist. This may include automated diagnostic pure tone audiometry for example.

13. Surely automated audiometry cannot be as accurate or reliable as manual audiometry conducted by an audiologist?

You have to remember that automated audiometry has been around for a very long time. In fact, it has been around as long as the first Bekesy audiometry description in 1947. We recently completed a meta-analysis of automated diagnostic pure tone audiometry compared to the gold standard of manual audiometry. The results show that automated audiometry is equally accurate and reliable, but with the acknowledgement that there is still a shortage of evidence for automated audiometry with bone conduction, in patients with various degrees and types of hearing loss and difficult-to-test populations (Mahomed, Swanepoel, Eikelboom, & Soer, 2013).

In some of our clinical research in this area we’ve been using an audiometer that has been developed specifically for telehealth purposes and includes an option for automated testing – it's called the KUDUwave and is produced in South Africa. Unique features include double attenuation (insert earphones covered by circumaural earcups), active monitoring of the environmental noise during testing and visual feedback on patient responses for remote testing. We’ve done a number of validation studies on automation, remote testing and testing in natural environment using this device (Maclennan-Smith, Swanepoel & Hall, 2013; Swanepoel, Mngemane, Molemong, Mkwanazi, & Tutshini, 2010; Swanepoel, Koekemoer & Clark, 2010; Swanepoel, Maclennan-Smith & Hall, 2013).

Figure 2. The KUDUwave audiometer.

14. The KUDUwave? I see how the “wave” may link with audiometry, but why “KUDU”?

If you’ve been on Safari in the African bush you’ll know what a Kudu is – it's a majestic African antelope and has some of the largest ears around. Since all the hardware for the KUDUwave audiometer is incorporated in the earcups they look like a Kudu’s ears and of course, these earcups monitor the environmental noise like a Kudu does to hear its predators.

15. The sound of “automated diagnostic audiometry” may be seen as a threat to audiologists – does this mean we’ll be replaced by technology?

Definitely not! But we certainly want to use technology to our benefit and to improve our efficiency especially in light of the increasing need for audiological service provision. For patients who are not difficult to test, automated audiometry could mean we have more time to help patients and we can devote our attention to more challenging tasks requiring our expertise such as differential diagnosis, counseling, hearing aid selection, fitting, verification and aural rehabilitation.

16. You certainly make it sound like there may be some sense in reconsidering our clinical traditions. What other areas of audiological practice have employed telehealth?

A few years ago, Jay Hall and I conducted a systematic review of the telehealth applications reported in audiology (Swanepoel & Hall, 2010). The scope of telehealth spanned various areas of audiological service-delivery including screening, diagnosis and intervention. Screening applications have been reported for several populations including infants, children and adults with feasibility and reliability facilitated through telehealth using both synchronous and asynchronous models. Although limited, diagnostic procedures reported on included audiometry, video-otoscopy, OAE, and ABR. All the studies confirmed clinically equivalent results for remote, telehealth-enabled tests when compared to conventional face-to-face versions. Furthermore, intervention studies through telehealth, including hearing aid verification, cochlear implant mapping and Internet-based treatment for tinnitus, demonstrated reliable and effective applications compared to conventional face-to-face methods.

Since this review additional studies have appeared in a number of additional areas of audiological practice demonstrating the potential benefits. As I mentioned earlier, in the US one important example is the VA who are one of the big drivers for tele-audiology services. In South Africa, the Department of Health’s division for multidrug resistant TB has deployed close to 40 telehealth stations for monthly audiological monitoring of hearing in almost 5000 patients with multidrug resistant TB who are receiving ototoxic treatment. These stations employ a telehealth-enabled automated diagnostic audiometer operated by a telehealth facilitator. Test results upload to a shared server for interpretation and monitoring by audiologists at regional public health care hospitals. This is an example of extending services through the use of an asynchronous telehealth model.

17. What about the perceptions of patients and clinicians using telehealth – how do they relate to services provided using telehealth means?

A common reservation amongst clinicians and patients is the perception that it may be difficult to establish a meaningful clinical relationship when the interaction is not a face-to-face onsite consultation. Telehealth services may however include initial contact with patients through face-to-face consultations with follow-up sessions using telehealth means.

Although the studies are limited, research to date reports that perceptions of patients and clinicians who have experienced tele-audiology services have all been positive. In a study on remote cochlear implant mapping, positive patient experiences on par with face-to-face assessments were reported (Ramos et al. 2009). Perceptions of patients who underwent an asynchronous online tinnitus treatment program also demonstrated similar perceived benefits to those who had face-to-face treatment (Kaldo-Sandström, Larsen & Andersson, 2004; Kaldo et al. 2008). More research is certainly warranted to provide further input, however.

18. Do audiological societies and regulating bodies support telehealth as a means of service delivery?

All the current position statements or resolutions on telehealth in audiology endorse and support its use to improve access to audiological services (Appendix A). There is general agreement that telehealth has the potential to overcome accessibility barriers related to geographic (e.g. travel distance and costs), meteorological (e.g. severe weather), restricted human resources in audiology, mobility, and personal patient schedule (work and family) disruptions that may hinder access to audiological services. Current guidelines and resolutions agree that the telehealth service must be equivalent to in-person service provision in scope and nature. Furthermore tele-audiology services should always be provided by, or supervised by, a qualified audiologist. The audiologist must be aware and accountable to the ethical and clinical standards of their professional regulating or licensing body and abide by these as specified for the state or province.

19. You’ve raised an interesting issue here. Does this mean audiologists can provide a telehealth service in a different state than the one they are licensed in?

These are important issues that are currently in the process of being addressed. At present some states in the US require that the professional be licensed both at the home state and in the state where the patient is being served. There is an increasing number of states, however, with telehealth provisions for audiology but is characterized by widespread variability (ASHA, 2012).

20. I hate to put this out there as the final question, but in the end I suppose it all comes down to the bottom line – can audiologists be reimbursed for their services if they are provided through telehealth?

As you rightly point out, this is the bottom line and unfortunately reimbursement and insurance coverage for telehealth services remains one of the most important reasons for the slow adoption. Increasingly, health authorities are changing their legislation governing reimbursement to incorporate telehealth services. Unfortunately, in many cases where reimbursement legislation includes telehealth, it often covers only certain types of services such as face-to-face consultations as opposed to store-and-forward services that are likely to hold more promise for improved time and cost efficiency. Since telehealth service-delivery, as part of regular reimbursement and insurance coverage programs, is currently in a process of change and development, it is important to verify funding sources that will cover the services prior to initiation of services (ASHA, 2013a).

This field changes very quickly and, hopefully, reimbursement and insurance coverage will catch up to allow for development of telehealth as a healthy part of “normal” audiological service delivery.

References

American Speech, Language and Hearing Association. (2012, April). State provisions update for telepractice. Retrieved from: https://www.asha.org

American Telemedicine Association. (2013). What is telemedicine? Retrived from: https://www.americantelemed.org/learn

Dharmar, M., Sadorra, C.K., Leigh, P., Yang, N.H., Nesbitt, T.S., Marcin, J.P. (2013). The financial impact of a pediatric telemedicine program: a children’s hospital’s perspective. Telemedicine and e-Health, 19(7), 502-508.

Fagan, J.J., & Jacobs, M. (2009, March). Survey of ENT services in Africa: Need for a comprehensive intervention. Global Health Action, 2, 1-8. doi: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1932

Goulios, H., & Patuzzi, R.B. (2008). Audiology education and practice from an international perspective. International Journal of Audiology, 47, 647-664.

Kaldo-Sandström, V., Larsen, H.C., & Andersson, G. (2004). Internet-based cognitive-behavioral self-help treatment of tinnitus: clinical effectiveness and predictors of outcome. American Journal of Audiology, 13, 185-192.

Kaldo, V., Levin, S., Widarsson, J., Buhrman, M., Larsen, H.C., & Andersson, G. (2008). Internet versus group cognitive-behavioral treatment of distress associated with tinnitus: a randomized control trial. Behavorial Therapy, 39, 348-359.

Maclennan-Smith, F., Swanepoel, D., & Hall, J.W.III. (2013). Validity of diagnostic pure-tone audiometry without a sound-treated environment in older adults. International Journal of Audiology, 52, 66-73.

Mahomed, F., Swanepoel, D., Eikelboom, R.H., & Soer, M. (in press). Validity of automated threshold audiometry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ear and Hearing.

Ramos, A., Rodríguez, C., Martinez-Beneyto, P., Perez, D.,Gault, A., Falcon, J. C., & Boyle, P. (2009). Use of telemedicine in the remote programming of cochlear implants. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 129, 533–540.

Swanepoel, D., & Hall, J.W. (2010). A systematic review of telehealth applications in audiology. Telemedicine and e-Health,16(2),181-200.

Swanepoel, D., Koekemoer, D., & Clark, J.L. (2010). Intercontinental hearing assessment: a study in tele-audiology. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 16, 248-252.

Swanepoel, D., Maclennan-Smith, F., & Hall, J.W.III. (2013, in press). Diagnostic pure-tone audiometry in schools: mobile testing without a sound-treated environment. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology.

Swanepoel, D., Mngemane, S., Molemong, S., Mkwanazi, H., & Tutshini, S. (2010). Hearing assessment – reliability, accuracy and efficiency of automated audiometry. Telemedicine and e-Health, 16(5), 557-563.

Windmill, I.M., Freeman, B.A. (2013). Demand for audiology services: 30-Yr projections and impact on academic programs. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 24, 407-416.

World Health Organization. (2011a). TELEMEDICINE, 2, 1–96. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf

World Health Organization. (2011b). WHO mortality data and statistics. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. Retrieved from www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/mortality/en/

Appendix A -Telehealth Position Statements

American Academy of Audiology. (2008) The use of telehealth/telemedicine to provide audiology services. Retrieved from: www.audiology.org/advocacy/publicpolicyresolutions/documents/telehealthresolution200806.pdf

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2005). Audiologists providing clinical services via telepractice: Position statement. Available from www.asha.org/policy

Canadian Speech, Language Pathology and Audiology Association. (2006). Position paper on the use of telepractice for CASLPA S-LPs and Auds. Retrieved from: https://www.caslpa.ca/system/files/resources/telepractice.pdf

Cite this content as:

Swanepoel, D. (2013, October). 20Q: Audiology to the people – combining technology and connectivity for services by telehealth. AudiologyOnline, Article 12183. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com