From the desk of Gus Mueller

I was at an airport not too long ago, getting ready to board a flight, when some sort of warning buzzer was triggered, similar to a fire alarm, only louder. It was nasty (that’s loose audiology-speak for 110 dB or higher), and I immediately wanted to get away, but there was nowhere to go. The reactions among the crowd were interesting—some were pretending like they didn’t even hear it, while behind me, a teenage girl was curled up in a ball against the wall with her arms wrapped over her head. The warning signal continued for several minutes, and when it stopped, I felt this huge sense of relief (the magnitude of which I hadn’t experienced since the day I was told I didn’t have to retake organic chemistry if I transferred into the speech pathology program).

I was at an airport not too long ago, getting ready to board a flight, when some sort of warning buzzer was triggered, similar to a fire alarm, only louder. It was nasty (that’s loose audiology-speak for 110 dB or higher), and I immediately wanted to get away, but there was nowhere to go. The reactions among the crowd were interesting—some were pretending like they didn’t even hear it, while behind me, a teenage girl was curled up in a ball against the wall with her arms wrapped over her head. The warning signal continued for several minutes, and when it stopped, I felt this huge sense of relief (the magnitude of which I hadn’t experienced since the day I was told I didn’t have to retake organic chemistry if I transferred into the speech pathology program).

We’ve all been around sounds in our environment that were just “too loud,” and sometimes they are so loud that we just wanted to get away. Depending on our mood, the level that triggers this reaction will vary but usually, these are sounds that have intensities of 80, 90 dB or higher. What if we were bothered by sounds that are much softer, sounds that occur often in our everyday lives? That’s this month’s topic at 20Q.

Hyperacusis is typically defined as an unusual intolerance to ordinary environmental sounds; sounds that are neither threatening nor uncomfortably loud to a typical person. While we normally consider it a rare event to see a patient experiencing hyperacusis, recent surveys suggest that the prevalence may be higher than we think. These prevalence studies, however, can be muddied, as the definition of true hyperacusis is somewhat varied. To complicate matters, we now frequently hear about other sound tolerance pathologies such as phonophobia, misophonia, and selective sound sensitivity syndrome, known as 4S. Clearly, we need an expert to help us understand all of this.

Hyperacusis is typically defined as an unusual intolerance to ordinary environmental sounds; sounds that are neither threatening nor uncomfortably loud to a typical person. While we normally consider it a rare event to see a patient experiencing hyperacusis, recent surveys suggest that the prevalence may be higher than we think. These prevalence studies, however, can be muddied, as the definition of true hyperacusis is somewhat varied. To complicate matters, we now frequently hear about other sound tolerance pathologies such as phonophobia, misophonia, and selective sound sensitivity syndrome, known as 4S. Clearly, we need an expert to help us understand all of this.

Most of you are very familiar with our 20Q author this month, James “Jay” W. Hall III. His distinguished 40-year audiology career began with his days in Houston, with extended stays in following years at Vanderbilt and the University of Florida. He now holds the academic appointment as Extraordinary Professor in the Department of Communication Pathology at the University of Pretoria in South Africa—and you thought your commute was bad! He also is Adjunct Professor in the Department of Audiology at Nova Southeastern University, and president of James W. Hall III Audiology Consulting LLC. The consulting corporate headquarters are located in the quaint village of St Augustine, Florida, with offices tucked away in the loft of a renovated 1907 Victorian home in historic Lincolnville, where Jay has an E800 Bekesy and a copy of CC Bunch's Clinical Audiometry at his side for constant inspiration.

In this excellent article, Dr. Hall walks us through what is known about hyperacusis, and how it differs from other sound tolerance disorders. As someone who has worked in the clinic with hyperacusis patients himself, I think you’ll particularly enjoy his insights on the treatment and management of this intriguing pathology.

Gus Mueller, Ph.D.

Contributing Editor

March 2013

To browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller articles, please visit www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Treating Patients with Hyperacusis and Other Forms of Decreased Sound Tolerance

1. It’s seems like I’m hearing more about hyperacusis these days. I also recently heard the unusual word “misophonia.” Is misophonia the same thing as hyperacusis?

1. It’s seems like I’m hearing more about hyperacusis these days. I also recently heard the unusual word “misophonia.” Is misophonia the same thing as hyperacusis?

All these terms can be confusing, so let's start with a brief explanation of terminology. David Baguley and Gerhard Andersson (2007) succinctly and clearly define hyperacusis as an “Experience of inordinate loudness of sound that most people tolerate well, associated with a component of distress ... this experience has a physiologic basis ... but it also has a psychological component.“ The term hyperacusis implies a reaction or intolerance to the physical characteristics of most sounds.

The term “misophonia” has a different meaning. Misophonia is a distinct irritation or dislike of specific soft sounds (Jastreboff & Jastreboff, 2013). The word literally means “hatred of sound.” Patients with misophonia often complain about very distinct sounds, such as those produced by a family member during activities like eating, chewing, swallowing, and lip smacking. The phrase Selective Sound Sensitivity Syndrome or 4S is used by some to describe the same phenomenon, but the term misophonia now seems to be preferred among audiologists.

I should add that hyperacusis, or some form of decreased sound tolerance, is more common than you might suspect. Based on telephone and Internet surveys the estimated prevalence is around 8 to 9%. Between 2 to 3% of the general population reports debilitating intolerance to sound that requires professional help.

2. Now I think I understand the difference between hyperacusis and misophonia, but 4S syndrome?! That’s one acronym I’ve never heard before. While we’re talking about terminology, what about phonophobia?

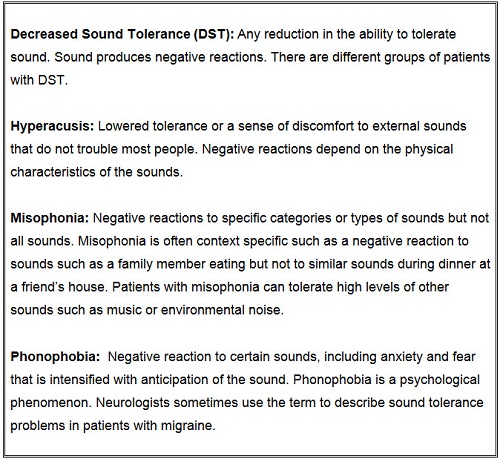

As you can probably figure out, the word phonophobia means fear of sound. It’s a reaction to and avoidance of certain sounds that involves anticipation, anxiety, learning and conditioning. A diagnosis of phonophobia has psychological implications for assessment and management so the term is falling out of favor among audiologists who evaluate and treat patients for hyperacusis. “Decreased sound tolerance” or DST is now used in referring to patients with various disorders involving intolerance to sound including hyperacusis, misophonia, and/or phonophobia (Jastreboff & Jastreboff, 2013). These terms are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of terms related to decreased sound tolerance arranged alphabetically.

3. O.K. I’ll remember to use the phrase “decreased sound tolerance” and to avoid the terms phonophobia and 4S syndrome. How can audiologists help patients with decreased sound tolerance?

We can talk about treatment later if you like, but let’s talk about assessment first. Assessment includes questionnaires, inventories, and special history forms in addition to hearing testing. The inventories and questionnaires provide valuable information on the nature of the patient’s decreased sound tolerance and its impact on quality of life. Tools like the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (Newman, Jacobson, & Spitzer, 1996) are also used for patients with hyperacusis. In addition, it's important to acquire information on the specific sounds that are bothersome. In case you’re curious, among the sounds most often described as aversive and producing annoyance are noise produced by vacuum cleaners, hair dryers, children crying, and sirens.

And, information about the patient’s decreased sound tolerance must be considered in the context of overall health status. Decreased sound tolerance, and especially hyperacusis, may be a symptom of a variety of central nervous system disorders like depression, migraine, post-traumatic stress disorder, Tay Sach’s disease, Ramsay-Hunt Syndrome, and multiple sclerosis, to name just a few. Hyperacusis is also reported by 40 to 50% of patients with bothersome tinnitus.

4. How about children? Is decreased sound tolerance associated with any specific pediatric diseases?

Absolutely, decreased sound tolerance including hyperacusis is often a symptom in children with Williams syndrome, autism, and even auditory processing disorders. I should also point out here that hypearcusis is sometimes cited as an adverse effect of certain prescription drugs that affect the central nervous system including Effexor, Prozac, Zoloft, and others.

5. For now, I’m mostly interested in patients who have decreased sound tolerance yet none of those serious diseases or disorders. What can be done for them?

Remember, effective treatment almost always follows an accurate diagnosis so let's get in to more details about evaluating patients with decreased sound tolerance. A comprehensive hearing test battery must be administered including, at the very least, otoacoustic emissions, pure tone audiometry for conventional and also high frequencies (up to 20,000 Hz), and loudness discomfort levels (LDLs). It should also include tympanometry and word recognition testing.

Diagnostic tests permit quick and confident differentiation of hyperacusis versus loudness growth patterns that are common with cochlear hearing loss. The findings for otoacoustic emissions measurement and pure tone audiometry are almost always normal in patients with hyperacusis. And hyperacusis is influenced by a patient’s emotional state.

6. Is word recognition testing possible with patients with decreased sound tolerance, due to potentially higher presentation levels?

You may have to use a lower presentation level than normal, perhaps conduct testing at a comfortable listening level. Since these patients typically do not have hearing loss, this level still should be adequate to obtain optimum performance, which usually is at or near 100%.

7. How about the measurement of loudness discomfort levels?

Measurement of LDLs with pure tone and speech signals is an essential part of the diagnostic test battery for assessment of decreased sound tolerance. Very low initial LDL values are very useful in documenting reduced tolerance to sound. Keep in mind, however, that LDLs in patients with hearing loss and no hyperacusis may be as low as 75-80 dB HL or so (e.g., Bentler and Cooley, 2001). In an audiology clinic, it’s not uncommon to encounter patients seeking help for hyperacusis who have LDLs as low as 60 dB HL and below. For patients with hyperacusis, repeated LDL measurements offer a way to quantify the effectiveness of treatment. I’ve had patients with hyperacusis whose LDLs increased with treatment from below 60 dB HL to over 85 dB HL in a matter of weeks.

8. Any hearing tests that should be avoided in evaluating patients with decreased sound tolerance?

I’m glad you asked that question. I certainly don’t recommend high level speech testing (looking for rollover). And definitely don’t conduct acoustic reflex measures. There’s no benefit to measuring these thresholds since most patients with hyperacusis have normal hearing sensitivity. It’s tempting to consider whether acoustic reflex thresholds would be unusually low in this patient population but the risk of exacerbating a patient’s hyperacusis is too high a penalty to pay to satisfy the curiosity. In fact, before even testing hyperacusis patients I strongly recommend that you take a minute to tell the patient that you have no plans to present any high levels of sound, and that he or she can stop any test if the sounds produce discomfort or anxiety. Believe it or not, some patients can’t tolerate the intensity of a probe tone in tympanometry or test signals in otoacoustic emission measurement. Worse than that, I’ve had patients with hyperacusis who were convinced that their problem with sound tolerance was triggered when another audiologist performed acoustic reflex measurement! Stay true to the old Hippocratic Oath, and “do no harm.”

9. You’ve kept me in suspense long enough. What can be done for these patients with decreased sound tolerance?

Your concern about management of decreased sound tolerance is understandable. There’s little value in assessing a problem if the assessment doesn’t lead to some form of treatment. In the past, patients with decreased sound tolerance rarely received evidence-based or adequate care for their problem. The management plan for patients with decreased sound tolerance is based directly on information from the history, inventories, questionnaires, and audiologic testing. Often a multi-disciplinary management strategy is needed.

10. Would you be a little more specific about multi-disciplinary approach?

Sure. A patient with a history suggesting possible central nervous system disorder like migraine or depression is referred to a neurologist or a psychiatrist. A child with sensory disturbances in addition to hyperacusis, including intolerance to light and tactile stimulation, is referred to an occupational therapist for evaluation of possible sensory integration disorder. Patients taking medications that are associated with hyperacusis need to consult with their family physician or the physician prescribing the drugs. And some patients with hyperacusis benefit from consultation with a psychologist who has expertise in cognitive behavioral therapy (Andersson, 2013).

11. Sounds reasonable. Are there any general management strategies that help most patients?

All patients with decreased sound tolerance can be helped. One of the first steps in management is to thoroughly explain the problem to the patient or the parents if the patient is a young child. It’s reassuring for patients and parents to realize that decreased sound tolerance is not uncommon and that there are experts available who can make an accurate diagnosis and coordinate effective treatment for the problem. Audiologic test results almost always confirm that the patient’s hearing sensitivity is entirely normal. Most patients with hyperacusis are worried about loud sounds damaging their hearing. It’s very reassuring for a patient to know that hearing test results are normal. Counseling is very important. In fact, for most patients with decreased sound tolerance counseling is intervention.

12. Counseling is intervention. I like that phrase. Are you suggesting that counseling is particularly important for patients with decreased sound tolerance?

Yes, counseling is essential for any patient with decreased sound tolerance. And, it’s directed to the specific problems the patient is experiencing. Counseling inevitably includes a recommendation for sound enrichment. In response to their discomfort with loud sounds, patients with hyperacusis tend to reduce their exposure to environmental sound stimulation. Some patients even regularly use earplugs or earmuffs to “protect” their ears from loud sounds. Unfortunately, these well-intentioned strategies further decrease tolerance to sound. Patients are strongly encouraged to surround themselves with soft and relaxing sound, and to progressively increase their exposure to typical everyday sounds.

Counseling must include a simple review of what is known about the underlying mechanisms of hyperacusis. Patients need to understand that their reaction to loud sounds is due to activation of parts of their brain that control emotional and fear responses to sound. For successful management of hyperacusis, patient knowledge is powerful. Obviously, the explanation of the mechanisms of hyperacusis is given at a level that the patient can understand. Remember my earlier comments about LDLs in patients with hyperacusis increasing dramatically with treatment? The treatment for those patients consisted entirely of counseling and sound stimulation.

13. That’s impressive. Is professional counseling from other disciplines ever needed for this challenging patient population?

Definitely. For most hyperacusis patients I begin the management process with intensive counseling and recommendations for sound enrichment. Patients are regularly followed either with clinic visits or at least email communication to monitor progress. A small proportion of patients with debilitating hyperacusis shows inadequate progress. I then recommend consultation with a psychologist, and preferably one with expertise in cognitive behavioral therapy (Andersson, 2013).

14. Cognitive behavioral counseling! I could use a little help myself. What other treatment options are available for patients with decreased sound tolerance?

A program to desensitize the patient to specific sounds is usually effective, in addition to general sound enrichment. Here’s how it works. You first question the patient or the parent of a child about the sounds that are most bothersome. Let’s say the list includes sounds from a vacuum cleaner, a barking dog, a child crying, thunder, a slamming door, and an ambulance siren. The patient or parent records the sounds on some device or, if that’s not possible, downloads sound clips from the Internet. Then the patient listens to the sounds for a period of about 15 minutes at least 4 or 5 days per week.

15. Sounds intriguing. Can you provide a few more details about how this training works?

Of course. I’ll even give you an example. First of all, it’s important for the patient to control the volume of the bothersome sounds during the desensitization sessions and to gradually increase the loudness from week to week. If the patient is a child, it’s also important for the parent to talk rationally with the child about the sounds. For example, “Emily, I know an ambulance sound is scary. I don’t like to hear the sound of an ambulance siren because it means someone is sick. But the person in the ambulance is going to a hospital where they’ll get better. And, you’re not sick or injured in an accident. The ambulance sound will be over soon and it won’t hurt your ears.” It’s quite remarkable how soon a patient with hyperacusis will begin to tolerant sounds that were once so bothersome.

16. Considering the differences between hyperacusis and misophonia that you’ve already described, I presume that treatment approaches are different for the two disorders?

There’s a difference in opinion among audiologists on how misophonia should be treated and which professional should be responsible for management. My approach begins with audiological management but it often ends with professional counseling. I first counsel extensively all patients with decreased sound tolerance, including those with misophonia. Sometimes a strategy of focused sound enrichment is very useful for patients with misophonia.

Let’s take as a sample case a 12-year-old boy who reportedly can’t tolerate sounds made by his mother during meals at home. His refusal to eat with the family has become a major domestic issue. Interestingly, the patient doesn’t experience decreased sound tolerance in any other situations, even during family meals without mother. In counseling the family, I would probably recommend that the boy be allowed to listen to music with his iPod or similar device during family meals with mom located at the other end of the dinner table. However, if the child’s misphonia and its impact on family dynamics persisted, then I wouldn’t hesitate to refer the family to a professional counselor or psychologist.

17. Are there other treatment options, maybe some evidence-based approaches, that are proven to help patients with decreased sound tolerance?

Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) and Neuromonics Tinnitus Treatment are two well-defined approaches that are available for patients who require more extended management than what we’ve already talked about.

18. Pardon my ignorance, but I thought tinnitus retraining therapy was only appropriate for tinnitus. It’s appropriate also for hyperacusis and other patients with decreased sound tolerance?

Yes, the underlying principles and rationale for the use of Tinnitus Retraining Therapy apply also for hyperacusis. I summarized the directive counseling component of TRT when I answered your question about how counseling is intervention. Directive counseling explains to the patient the role of increased gain within the central nervous system and the emotional (limbic system) and fear (autonomic system) responses to sound in hyperacusis. Directive counseling also educates the patient about how sound therapy can take advantage of brain plasticity to promote habituation or readjustment to sound. Evidence from formal studies published in peer-reviewed journals supports this management strategy (e.g., Formby, Sherlock & Gold, 2003; Formby et al., 2008; Jastreboff, 2007; Jastreboff & Jastreboff, 2013) and findings from ongoing large scale clinical trials will be available soon. I should clarify here that TRT is not appropriate for patients with misophonia.

19. All this sounds very positive but there must be some patients with severe decreased sound tolerance who just can’t be helped.

Not really. All patients with decreased sound tolerance can be helped. That’s my first message to a patient with hyperacusis. An appropriate treatment strategy based on an accurate assessment and diagnosis will improve quality of life for all patients with decreased sound tolerance. It’s true that some patients will progress more rapidly and an occasional patient will not return to normal sound tolerance, but all can be helped.

20. Any new treatments for decreased sound tolerance on the horizon that we haven’t covered yet?

I’ve been around this business long enough to know that new and improved treatment options are inevitable as long as research efforts continue. Basic and clinical research on hyperacusis has increased dramatically in recent years. I have no doubt that patients will benefit soon from our increased understanding of this fascinating disorder.

References

Andersson, G. (2013). The treatment of hypearcusis with cognitive behavioral therapy. ENT & Audiology News, 21, 86-87.

Baguley, D.M. Hyperacusis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96, 582-585.

Baguley. D.M. & Andersson, G.A. (2007). Hyperacusis: Mechanisms, diagnosis, and therapies. San Diego: Plural Publishing.

Baguley, D.M. & McFerran, D.J. (2011). Hyperacusis and disorders of loudness perception. In A.R. Moller, B. Langguth, D. deRidder & T. Kleinjung (Eds.), Textbook of tinnitus. New York: Springer.

Bentler, R.A. & Cooley, L.J. (2001). An examination of several characteristics that affect the prediction of OSPL90 in hearing aids. Ear and Hearing, 22(1), 58-64.

Fagelson, M. (2013). Military trauma and its influence on loudness perception. ENT & Audiology News, 21, 80-81.

Formby, C., Sherlock, L.P. & Gold, S.L. (2003). Adaptive plasticity of loudness induced by chronic attenuation and enhancement of the acoustic background. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 114, 55-58.

Formby, C., Hawley, M., Sherlock, L., Gold, S., Segar, A., Gmitter, C., & Cannavo, J. (2008). Intervention for restricted dynamic range and reduced sound tolerance. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 123, 37.

Jastreboff, P. (2007). Tinnitus retraining therapy. Progress in Brain Research, 166, 415-423

Jastreboff, P. & Jastreboff, M. (2013). Using TRT to treat hyperacusis, misophonia and phonophobia. ENT & Audiology News, 21, 88-90.

Newman, C.W., Jacobson, G.P., & Spitzer, J.B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 122(2),143-148. doi:10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007

Cite this content as:

Hall, J. W. (2013, March). 20Q: What can be done for patients with hyperacusis and other forms of decreased sound tolerance. AudiologyOnline, Article #11679. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/